Cookbooks are more than collections of recipes. They may have a theme (Appetizers! Cookies! Tacos!) or showcase a particular cuisine (Thai, Italian, Parsi). Some cookbooks tell stories to contextualize their dishes or ingredients, offering the history of a meal or its place in a holiday tradition. Others provide detailed instructions about technique, inviting the reader to start with this recipe, then try other ingredients using the same method.

But cookbooks are also products of their time. Just compare the aspics, crown roasts and cheese balls found in Helen Corbitt’s 1957 classic with the sous vide chicken breasts and kale salads in a contemporary volume. Cookbooks reflect not only trends in food preparation and flavors but also the availability of ingredients in a certain era and region.

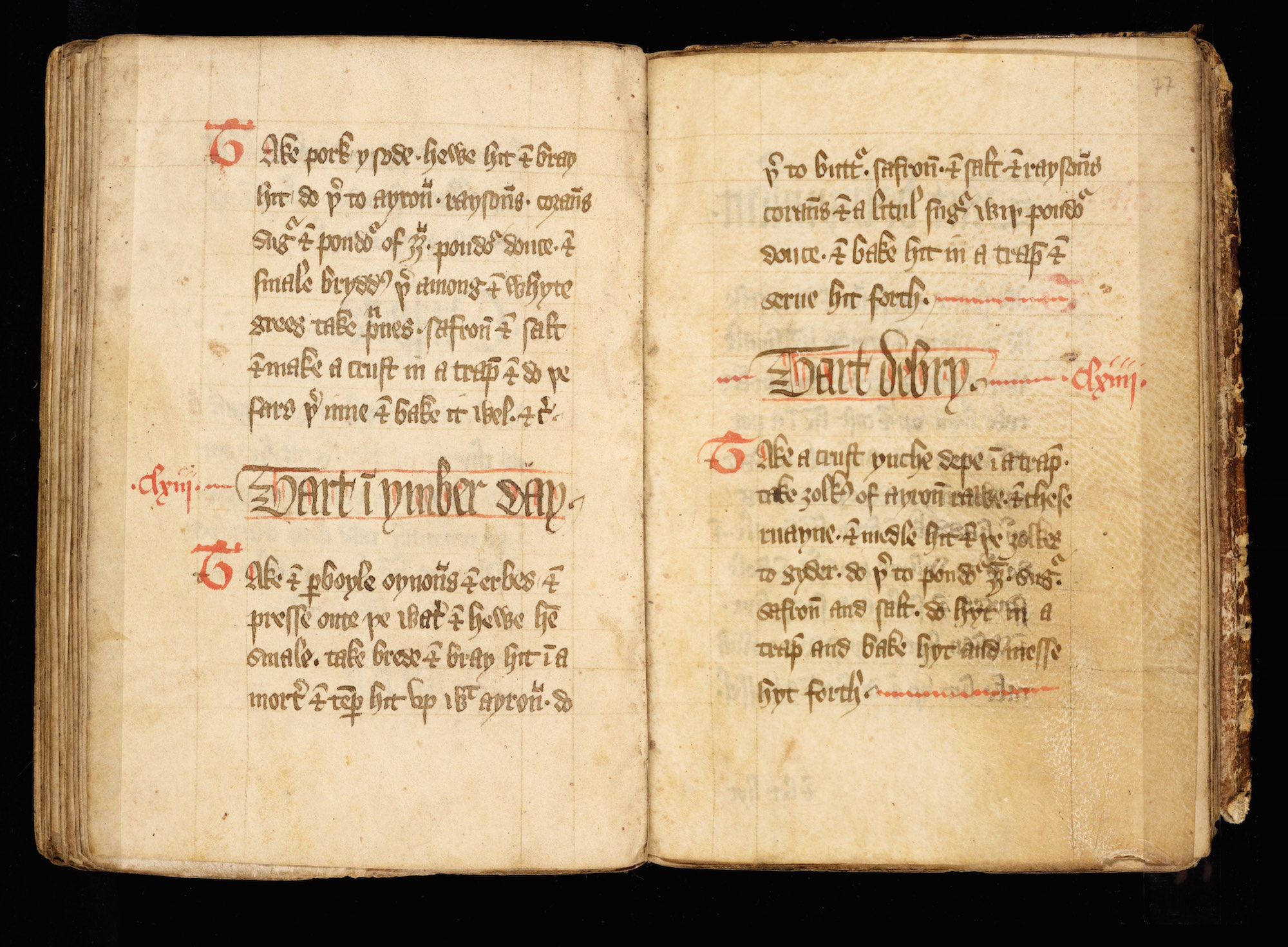

Take, for instance, “The Forme of Cury,” a collection of recipes recorded by a master cook working in the court of King Richard II. It’s one of the earliest known cookbooks and was probably made as a record of food served, rather than as a working cookbook. There are a handful of copies, all handwritten before the advent of printing centuries later.

“There’s no way really to tell if anyone ever used them, unless you look at the stains on them,” says Ken Albala, a Renaissance historian and food scholar at the University of the Pacific. “Chances are these were not brought into the kitchen, because usually cooks were not literate. But whoever wrote these down obviously was.”

Some of the ingredients used in 1390 will seem quite familiar: game (consumed more by nobles with estates), pork, chicken, butter, cheese, eggs, vegetables, spices. But the preparations differ from dishes we eat today. “The way they think of food, the colors they like, the flavors, the textures, the ingredients — it’s a completely different cuisine” than contemporary European fare, Albala says.

The origins of much medieval cuisine are in the Muslim Middle East, Albala explains. Those ingredients and techniques moved to India with Mughals and then to Spain and the rest of Europe. From there they traveled to Mexico with the conquistadors in the 1500s. “The moles of Mexico are the long-lost cousins of the curries in India,” Albala says.

Tart in Ymbre Days, as prepared by the author. It’s basically an onion frittata, dotted with raisins and delicious with a salad.

The generous use of spices in royal repasts was a display of wealth and status. Pepper and cinnamon traveled from India, while cloves and nutmeg originated in Indonesia and ginger came from China. Passing through the hands of Arab and Venetian merchants during their years-long journey, the exotic spices in use in the 14th century were exorbitantly expensive, accessible only to the wealthy.

While spices were sold in apothecaries, staples, such as milk, cheese, butter, grains and bread, were available in food markets, set-ups that resemble our modern farmer’s markets. “Food markets go back to ancient times,” Albala says. “In England, there are markets that started in the middle ages that are still there.” As with any type of market, the laws of supply and demand came into play. In the years following the plague — the period in which the Forme of Cury was written — the population was down, so wages were higher; thus, meat consumption also increased. As the population rebounded, wages fell, and the poor ate less meat.

Diets of the 14th century were influenced by more factors than just the availability of ingredients. Religious traditions and dietary rules informed daily menu planning. “Religion determined what you could eat seasonally and during fast days,” Albala says. “Lent, vigils of saints’ days — probably a third of the whole calendar is fasting.” The Tart in Ymbre Days recipe on this page is a kind of crustless quiche that contains onions, eggs, greens, raisins and “powder douce,” a common mixture of ginger, cinnamon and sugar (the original pumpkin spice!). Ymbre Days are quarterly sets of fasting days that mark the seasons of the Christian calendar. Because they fall outside of Lent, they were considered moderate fast days: meat was prohibited, but eggs were not.

Ken Albala, Renaissance historian and food scholar at the University of the Pacific. Check out his Food Rant.

Check out Ken Albala’s explorations of world cuisines, his cookbooks and his Great Courses on food and history.

Knowledge about fast days and how to put meals together would have been passed down orally, by peasant families and royal kitchen staffs, without the use of cookbooks. For one thing, most cooks weren’t literate. “We learn by looking and hearing and smelling, and not approximating through words,” Albala says. In fact, the whole notion of learning through cookbooks is a practice that may not last much longer, Albala believes.

“I think in the future we’ll have interactive videos, or some kind of instructional media where you can stop and ask questions, look closely and zoom in,” Albala says. “Perhaps something that will know what ingredients you have in the kitchen, know what kind of equipment you have, will adjust for your altitude or your allergies and could make working recipes for you. I think probably in our lifetime we’ll see cookbooks go extinct, or they’ll just be a rare, interesting artifact for people who like to collect them.”

Are you moving away from cookbooks to other kinds of instructional media? Which cookbook taught you the most? Tweet us @foodcityorg.

Author

Cory Leahy — editor, writer, runner, enthusiastic cook and veggie-leaning omnivore — has spent 20 years as an editor of books, magazines and websites. She recently stepped out of familiar labels to reimagine a next chapter that's all about food.