The Kimball Art Museum portrays a side of the meat business many visitors to Forth Worth, Texas, don’t see. If you only toured the Stockyards outside the museum, you’d miss the preceding centuries of carnivorous history.

In the late 1580s, Annibale Carracci painted two canvases that give us an idea of how meat fit into urban landscapes during Italy’s colorful Renaissance. By the late 16th century, Renaissance art entered the period of Mannerist painting, which led to the Baroque period, when the ideal proportions of High Renaissance art became exaggerated and even distorted. In the early 1580s painting, The Butcher’s Shop, Carracci’s two butchers and their gory background are examples of less-than-idealistic settings and out-of-proportion humans. The animal bodies outweigh the human bodies, and heads become dwarfed by torsos.

Called genre paintings, these images of everyday life stand in sharp contrast to the mythic portrayals of religious figures that hung in the Italian churches. Carracci, in one of his two paintings of butchers (the other, larger butcher scene is in the Christ Church Collection, Oxford, England), shows us one day — any day — in the life of a 16th-century butcher. He knew their lives because several of his family members were butchers in Bologna.

“One looks directly at you in defiant confrontation, as if he’s daring you to accept the reality of his profession with all its gore.”

There are two butchers in the Kimball Museum painting. One looks directly at you in defiant confrontation, as if he’s daring you to accept the reality of his profession with all its gore as he holds out a cut of meat for consideration. The other, eyes cast downward toward his knife, is preoccupied with the work of the day. Carracci studied with Titian in Venice, and the latter’s iconic red spills onto the canvas. There’s no blood on the floor — it’s not that messy — but the hanging carcasses are almost like stage backdrops surrounding the two men as they display their art and prepare for the next animal to slay. Nothing glorified here, but everything to see.

The carcasses suspended from sturdy meat hooks above the two figures appear to be from sheep. One sheep’s head lies at the feet of one of the butchers, one of its eyes cast in the direction of another sheep hanging above, eviscerated and waiting to be skinned.

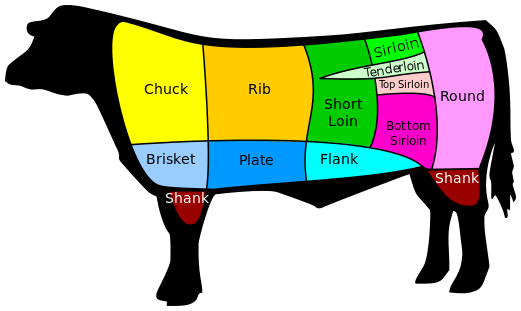

A beef carcass dominates the left-hand side of the painting, cut in half as is still the custom for wholesale cuts of meat, which today would include all eight primal cuts. (Those are chuck, rib, loin, round, flank, short plate, brisket and shank.)

We can’t tell from the painting if these are retail or wholesale butchers, but both existed throughout Europe at the time.

Outside the Kimball

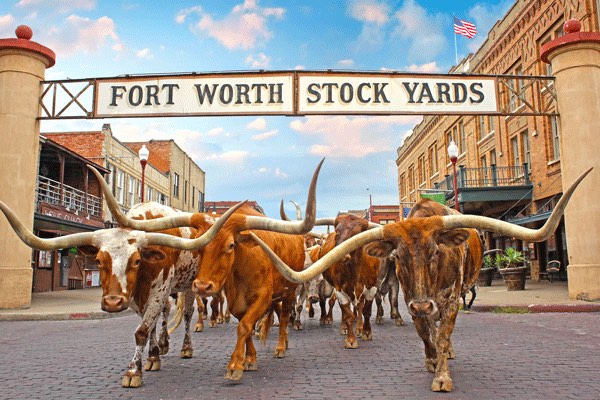

Outside the museum are the Fort Worth Stockyards, whose story is more familiar for Americans who know about the role that Forth Worth played in the history and development of the U.S. meat industry. The names of Armour and Swift, written in the embankment that surrounds the Stockyards, tell visitors who made Forth Worth the largest feeder of cattle from the Western ranges.

In their new incarnation as a tourist site, the Stockyards entertain visitors with twice-daily reenactments of cattle droving. Texas Longhorns plod silently down the street attended by cowboys located in the traditional positions of a droving team.

Inside the surrounding buildings, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, packing houses practiced the art of butchering in much the same way as those Italian butchers in Carracci’s paintings. Now, in Brooklyn and other foodie destinations, shops like those in the paintings are few but gaining more appeal as consumers demand more transparency between their food (meat in this case) and their plates. Perhaps it’s time for a contemporary painter to record those new Brooklyn butchers — pristine white aprons and all.

Author

The same sense of wonder that called Dr. Robyn Metcalfe to run the great deserts of the world has led her to take on the task of mapping our current food supply. A historian, desert distance runner and food futurist with a lifelong hunger to take on irrational challenges, Robyn Metcalfe marvels at what it takes to simply create a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.