Long before STEM initiatives came about, home economics programs may have done more than we know to bridge the gender gap in science.

A colleague of mine at The University of Texas at Austin invited me to peer into some locked bookshelves located in a conference room in the School of Human Ecology. The bookshelves, hidden from view by wood cabinets that line the perimeter of the room, contain stacks of musty books that have been neglected since the school was renamed during the 1980s, when university administrators, flummoxed by feminists, scuttled home economics departments.

The books and magazines inside the wooden cabinets once stood proudly on the bookshelves of the home economics department. Now the books lie in disheveled stacks, enshrouded in a past of denial and self-deprecation. Most have names of students or faculty inscribed on their flyleaves. They all reveal a past in which we believed students should know how to cook, make and repair everyday tools and operate within a world that considered personal responsibility to be a life skill.

Looking up from your latest, Pinterest-fueled attempt to make artisanal bread, you note that those books sound like something you’d like to read. I say UT’s hidden books should come out of the closet, and so should all former home economics departments, declaring a new, informed purpose more relevant than ever before.

Some of the books are about topics that would be familiar and celebrated by admirers of Michael Pollan, David Chang, Mark Bittman or Marion Nestle. Authors who wrote about food science, chemistry and the science of nutrition could have been muses to modern day molecular gastronomists such as Heston Blumenthal, Nathan Myhrvold and Homaro Cantu.

UT’s hidden books should come out of the closet, and so should all former home economics departments, declaring a new, informed, purpose more relevant than ever before.

Take, for example, A Laboratory Course in Physics of the Household, written by physics professor Dr. Carleton John Lynde. Published in 1919, the book was for high school students preparing for their College Entrance Board exams. The author points out that his book contains experiments and exercises — it is essentially a book of physics principles along with experiential learning activities. He also points out that any kitchen would serve as an adequate physics laboratory, equipped with standard weights and measures, both metric and non-metric.

Sure, it’s a guy writing for gals, but consider the times: Before 1920, American women did not even have the right to vote. But they were considered capable of understanding the principles of physics, a subject many women dismiss today. Barely 20 percent of all doctorates in physics are given to women, and our government has to develop programs such as STEM to encourage women to consider science as a course of study. Lynde’s book makes no apologies for his readers as it covers the principles of physics in 135 pages.

“Barely 20 percent of all doctorates in physics are given to women…”

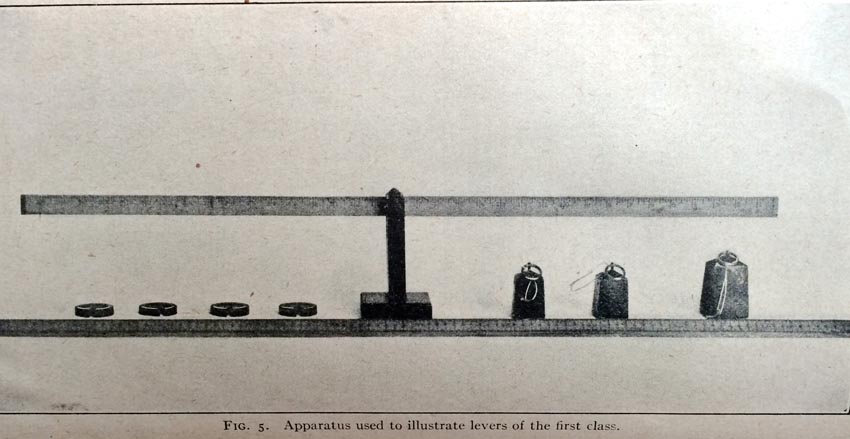

The book is divided into the common categories of physics: mechanics, heat, electricity and magnetism, light and sound. You can see from this photo that a reader learns about the principle of levers by making a fulcrum with a yardstick and several weights made out of cotton bags filled with sand or shot. (Shot wouldn’t be something you’d find in a book today….) The reader becomes familiar with the scientific method and the careful processes required to create an experiment.

In setting up each experiment, Dr. Lynde encourages the reader to write down the expected results and, later, to compare what actually occurred with the imagined results. I wonder how many of us think in such constructive ways, allowing for imagined outcomes and then taking the time to carefully learn from the real outcomes of any endeavor we may undertake.

The author says, “You will get a great deal of pleasure out of this work at home, because you will find it very exhilarating to make experiments of your own; you will get a great deal of profit also, because when you have planned and made experiments of your own on a given subject, you will find that you know it in a way you never could simply by making the experiments in school.” Never has an experiment about levers promised such exhilaration, pleasure and satisfaction.

By the eleventh experiment, you learn about Boyle’s Law by setting up experiments that use a fire extinguisher and a vacuum cleaner. Boyle’s Law explains how the volume of gas varies inversely as the pressure on it. The fire extinguisher comes in handy as an illustration of how the contents behave under pressure, and the vacuum cleaner is a rough example of how air pressure creates a vacuum.

This book is only one of many chestnuts rumbling around in those wooden cabinets in the School of Human Ecology. Aren’t Michael Pollan and others making the same call to experiment by making things — even promising “exhilaration” in much the same way as Dr. Lynde did in 1919? Perhaps it’s time to shine some sunlight on their covers and recognize how science education was reaching women even before initiatives like STEM, even if they were still confined to their kitchen laboratories.

So let the efflorescence of home economics begin. Let’s take home ec back, men and women, making useful stuff and learning about science and engineering along the way.

“You will get a great deal of pleasure out of this work at home, because you will find it very exhilarating to make experiments of your own; you will get a great deal of profit also, because when you have planned and made experiments of your own on a given subject, you will find that you know it in a way you never could simply by making the experiments in school.”

— Dr. Carlton John Lynde

Author

The same sense of wonder that called Dr. Robyn Metcalfe to run the great deserts of the world has led her to take on the task of mapping our current food supply. A historian, desert distance runner and food futurist with a lifelong hunger to take on irrational challenges, Robyn Metcalfe marvels at what it takes to simply create a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.