The traffic jam to enter the world’s largest food market begins around 3 a.m. Trucks of all sizes stream in, heavy with oranges from Veracruz or chiles from Chihuahua, manned by drowsy drivers who left their hometowns the day before to make the trip.

Imported cargo arrives via shorter daily runs from the neighboring international airport, and still other lorries cross several countries via the Pan-American Highway to sell their goods at Mexico City’s Central de Abasto.

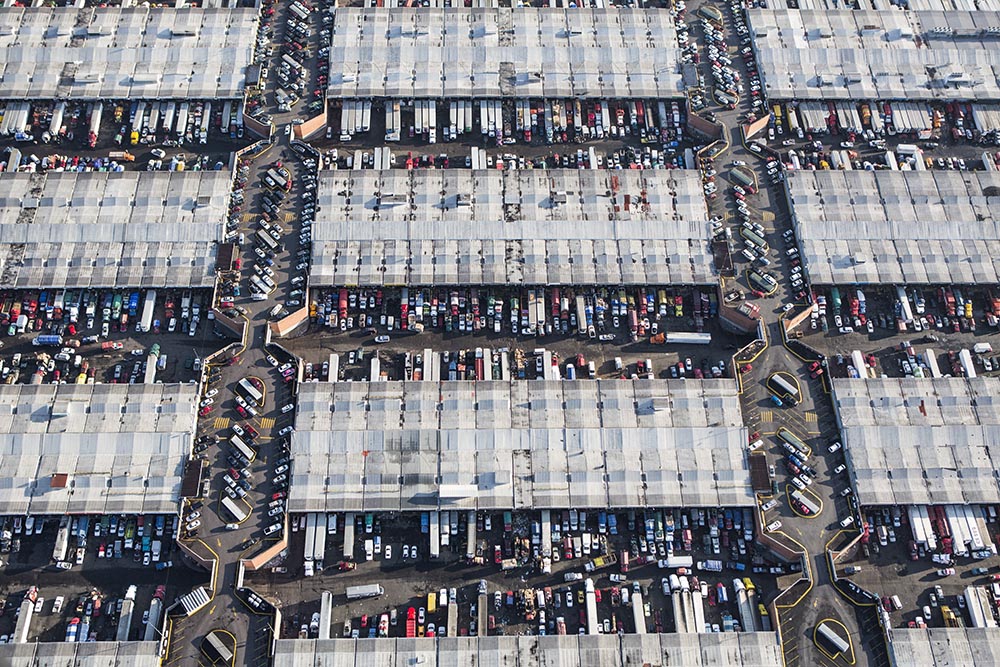

Open 365 days a year, this mega-market welcomes over 350,000 visitors daily. It formally employs 70,000 people and informally many more, including over 12,000 cartilleros — delivery men with dollies — each day. The market handles more than 30,000 tons of food daily, representing approximately 80 percent of all the food consumed in the metropolitan area and about 30 percent of the food consumed in the country.

Feeding a city of 21 million inhabitants is no easy task, which is why this market has its own zip code, an independent governing body and even its own 700-man police force, which comes in handy considering more than $9 billion changes hands annually, mostly in cash. This makes Central de Abasto one of the largest economic centers of operations in the country, second only to the Mexican Stock Exchange.

Feeding a city of 21 million inhabitants is no easy task, which is why this market has its own zip code, an independent governing body and even its own 700-man police force, which comes in handy considering more than $9 billion changes hands annually, mostly in cash. This makes Central de Abasto one of the largest economic centers of operations in the country, second only to the Mexican Stock Exchange.

Designed by architect Abraham Zabludovsky, Central opened its doors in 1982 in Ixtapalapa, southeast of the city center. The project grew from necessity: The former wholesale market, La Merced, had overwhelmed the centro histórico with traffic and lacked the necessary infrastructure to deal with the growing demands of the city. Of the market’s eight major sectors, Central’s fruit and vegetable area is the largest. Forty interwoven aisles stretch 140 acres, with 64 interior loading docks. All in all, that’s the length of 105 football fields, each piled high with produce. Most aisles sell mayoreo, wholesale quantities of 5 kilos or more, but several aisles provide menudeo, smaller quantities for the general public.

Hangar-style sections outside boast even cheaper prices. The subasta (auction) area, closed to the general public, hosts the first step in the chain of sale as middlemen negotiate prices for full trucks of produce directly with providers. Giant arched metal roofs top the open-air flower and vegetable area, where growers sell a variety of fresh goods to other vendors or directly to the public in a morning frenzy. Both areas are picked clean of merchandise by 8 a.m.

The flow of goods throughout the market and to the points of distribution beyond its walls relies on the 12,000 cartilleros who rush through the corridors daily. Anyone with an ID and $1.20 can rent a dolly, but efficient and reliable cartilleros build a client base and make more money than beginners. It’s tough work, hauling up to half a ton of food in a single trip, navigating the jam-packed aisles during the busiest hours of 4 a.m. to 6 a.m. The elevated bridges connecting the corridor of bodegas to the hallways that lead to the outside parking lots provide a special challenge. Workers run quickly to gain momentum for the steep summit. They pause on top for a rest, then begin an equally difficult descent, with no brakes and a heavy load. A coded language of whistles fills the air and helps the cartilleros communicate with each other. “I’m on your left!” sounds different than “Move over, I’m coming through!”

Author

Blair Richardson is the founder of Little Mule Studio, a graphic design and branding firm in Mexico City.