Grocery Stores: The IoT of Food

Tired of comparisons to the much flashier internet, supermarkets are working hard to ditch their unsexy descriptor: big-box stores. These days you’ll find a Murray’s Cheese outpost in Kroger, a kombucha bar at Whole Foods and poke bowl counter at Albertsons. All these flashy foodie options are good distractions from what’s happening under the hood, which is that grocery stores — the physical four walls — are going digital.

Ready or not, consumer packaged goods (CPGs) — those pre-wrapped items found in so many center aisles — are nudging grocery stores into the future. And so is Amazon. The online retail giant’s entrance into brick-and-mortar supermarkets forced every retailer to innovate or die.

It’s been decades since the internet changed the way we shop, so why are American retailers slow to get on board? The founders of Trax, a retail technology firm based in Singapore, might point to our love for the status quo. The U.S. Census Bureau’s figures (from second-quarter 2018) bear that out, indicating that e-commerce sales account for 9 percent of total sales. That means 91 percent of sales still occur in stores. Maybe U.S. retailers aren’t scared yet?

In contrast, the true retail visionaries are found in Australia, Brazil and China. Yair Adato, Trax’s chief technology officer, says China is five years ahead of the U.S.

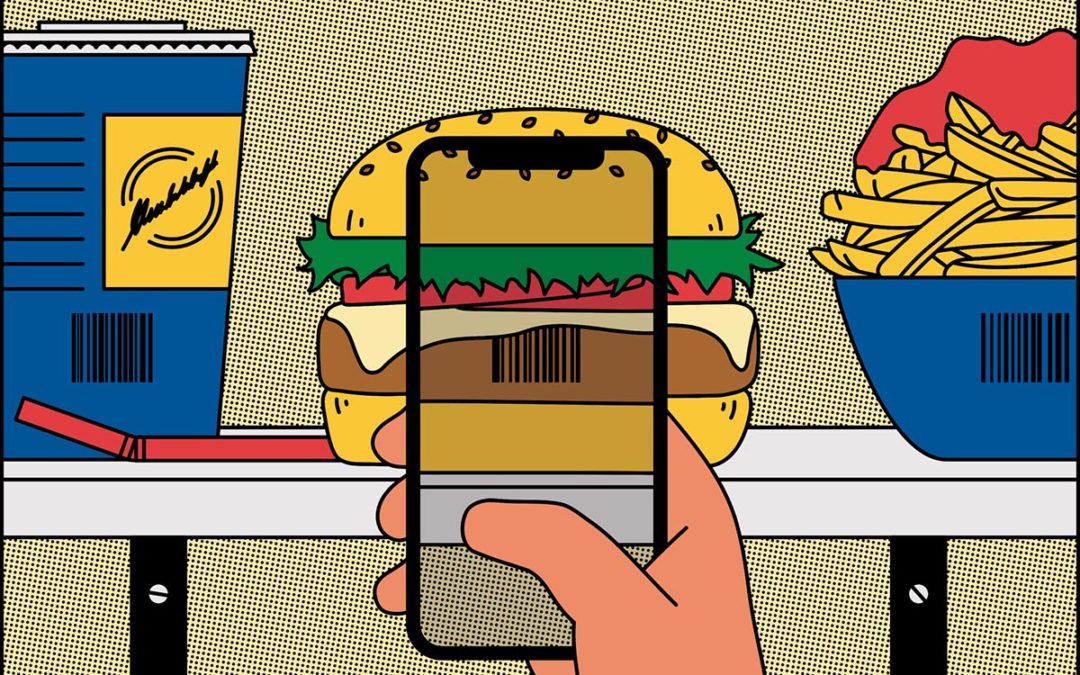

“In China, you can go to a store, scan what you want to buy, put it in your cart and they’ll deliver it to your home in 30 minutes,” Adato says.

Soda giants were early pioneers in creating speedy distribution channels. Yet despite raking in billions of dollars in sales, they couldn’t point to exactly how, when or why. Brands were guessing what was on the shelf, how much was left, what was selling at what times of day and even what their competitors had on the shelf. Short of physically walking in to every single store in the world and snapping a photo of the soda aisle, they had no idea what was happening.

In some countries, brand managers might have trusted their employees when they said they went to a store and reported that everything “looked good.” But in China or Brazil, managers wanted visual proof. “It’s a culture thing,” said Adato. “I want to know that I paid the right bonus to my employee.” In Australia, instead of proof, they wanted to improve processes using data analytics.

But it was a little bit like the chicken and the egg. Brands wanted to harness data to make better business decisions, and stores wanted to evolve. They saw that online shopping was more engaging for customers than a trip to the store, but it was an expensive undertaking with no clear financial incentive for either party. While a brand like Coke might want to push retailers for improved ways of tracking its sales, the reality is that it has only a few thousand SKUs (aka, inventory items). Target, on the other hand, has hundreds of thousands. But before it could become cost-effective for retailers to adopt new tracking tools, the technology — sensors, beacons, cameras — needed to advance.

In 2010, Trax began offering its image-recognition software, which incorporated physical images (taken by humans) and store data (including store layout and register sales), then stitched them into one actionable gold mine. For the first time, sales teams could have detailed product and category information including out-of-shelf, share-of-shelf, planogram, pricing and promotional compliance delivered to their mobile phones in real time. This was something managers could trust.

“In a grocery store there is so much dynamic movement,” says David Gottlieb, vice president of retail at Trax. “Something like 40 percent of products will change — a new item, or line extensions and new packaging.” Gottlieb deeply understands the in-store problem.

“Manufacturers are using us, even without feet on the street [robust sales teams] to collect information to get true metrics as to what degree their customers are making perfect stores, and that incentivizes the sales team to do a better job,” explains Gottlieb. He joined Trax in 2018 when the company purchased his startup, Quri, which used a crowdsourcing model to leverage large groups of people to perform paid “microtasks,” like taking images of store shelves.

With the acquisition, Trax now has half a million shoppers active in 6,000 U.S. cities with access to 150,000 stores. Despite this, the company is moving beyond human photographers and is beginning to install battery-operated internet-connected cameras underneath the shelves. The cameras take photos every minute of the day.

“It creates opportunity for use cases — like intra-day replacement,” CTO Adato says. “Our customers are looking at how long things last. That’s an indicator of lost sales that wasn’t available.” CPG clients that use Trax report their out-of-stock rates reduced by 10 to 15 percent and category sales (e.g., soda, crackers or condiments) increased by 3 to 5 percent.

While Trax was homing in on the perfect store, Shelfbucks, an Austin-based technology startup, was grappling with another unknown: marketing. Brands were spending money on in-store product merchandising displays to promote their products, but they had little idea what worked or whether they even made it to the floor. Erik McMillan, the CEO of Shelfbucks, made a fairly compelling argument for his technology: “You spend a $100, and you’re wasting $50.”

Through a fortuitous meeting with two of the biggest display producers in the U.S. — West-Rock and Menasha Packaging Co. — McMillan gained access to an untapped business opportunity that helped brands answer their age-old question: Does my marketing have an ROI?

If it sounds like meta-marketing-speak, that’s because it is. You send a physical piece of signage into your supply chain and on the other end it arrives at a store. It’s supposed to be put up somewhere, on the end cap (those shelves at the end of each aisle often filled with promotional items) or the shelf, but maybe it never makes it out of the back room. With no analytics, you’re left hoping for the best. Given the amount of money spent on merchandise promotion whose effectiveness can’t be tracked — a waste factor of 50 percent, according to McMillan — in-store marketing isn’t much better than shooting in the dark.

In coordination with brands, Shelfbucks puts sensors on displays, and in coordination with retail customers, it places sensors throughout stores. The sensors track the movement of the signage — whether it’s in the back room or out on the floor. When there are problems, Shelfbucks gets an exception report, which is sent to the store manager as an alert in the store’s task management system.

“We are literally generating data about something (store managers have) never seen before,” McMillan says. In 2014, one of Shelfbucks first customers was CVS Pharmacy; today Shelfbucks is in CVS stores nationwide. Fresh food is his next target. “We are focused on the three national chains: Kroger, Albertsons and Ahold USA.”

How these changes benefit consumers is open for debate. Perhaps it’s as simple as knowing our favorite soda — Dr Pepper Vanilla Float, perhaps — will never be out of stock again. And while it may seem as if the CPGs of the world are driving change, McMillan reminds us otherwise.

“Brands can’t force retailers to do anything. Retailers have the power. That’s a really important point,” McMillan says. “The brands have the money, and the customer buys their product, but the retailer owns the shopper.”

For a deep dive into grocery store technology, read Joseph Turow’s book, “The Aisles Have Eyes.”

For a deep dive into grocery store technology, read Joseph Turow’s book, “The Aisles Have Eyes.”

Wi-Fi

Wi-Fi Bluetooth

Bluetooth Apps on Our Mobile Phones

Apps on Our Mobile Phones Hidden Cameras

Hidden Cameras

Merroir

Merroir