Growing up playing in the alluvial soil of farms along the Mississippi River, I gleaned a vague notion of the importance of barges. These flat-bottomed, square-ended boats — whether towed, pushed or self-propelled — are used primarily to haul cargo. My granddad owned a small red and white one that was rusty around the edges. He used it to transport tractors, farm supplies and crops back and forth from his island farm in the Mississippi River.

As a youngster, I often visited Lock & Dam 24 in Clarksville, Missouri, to watch the low-slung hopper barges loaded with Midwestern grain travel through the locks with the help of towboats. Contrary to their name, the towboats gently push — rather than pull — the barges into the lock, a 110-foot-wide and 600-foot-long concrete chamber built between the riverbank and the dam. Locks, along with dams, create a step-like system that helps vessels navigate the changing elevations of the river.

There are many types of barges: A dredging barge is basically a clamshell bucket excavator on a floating platform. In China’s Grand Canal, self-propelled barges sport a cabin and motor at the back. Decades ago, sail-powered Thames barges plied England’s coasts and rivers. Barges are even used as ocean-going landing pads for SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rockets.

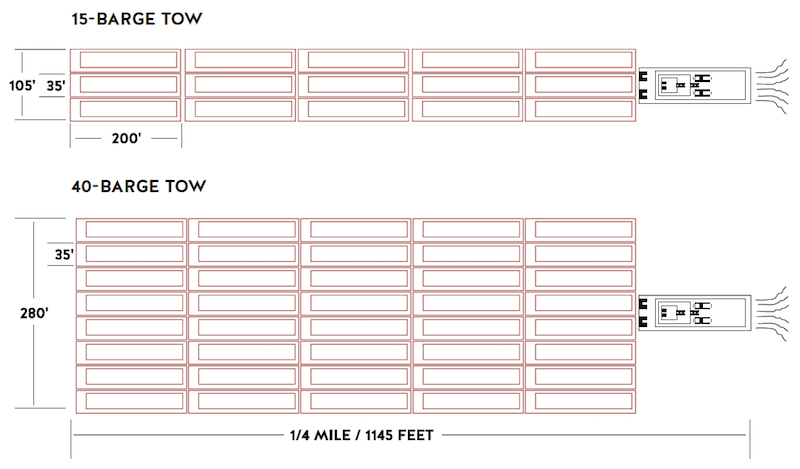

But the hopper barge that has become integral to the modern food system, especially in the United States, is a 200-foot-long, 35-foot-wide, 13-foot-deep boat with a large fiberglass cover. These barges are perfect for transporting bulk, dry cargo like grain or coal. They have no engines. Instead, they are designed to be lashed together with a web of steel cables into groups of two to 70 barges, known as tows, and pushed by a single towboat.

Towboats vary in size depending on how many barges they will be pushing and how and where they will be operating. Most are diesel-fueled and include a pilothouse that rises three to four stories above the deck, a kitchen, and quarters that house a crew of eight to 10 people. The average crew includes a captain and a pilot who alternate six-hour shifts in the pilothouse, a cook, a mate, four deckhands and an engineer. Crews serve 28-day stints, usually taking a four-week break before returning to the river.

LOCK AND LOAD

Hopper barges haul corn, soy, wheat, fertilizer and other bulk dry goods, primarily on the Mississippi, Ohio and Illinois Rivers. But they don’t travel alone. The standard tow on the Upper Mississippi is 15 barges, or five rows of three barges abreast, a bundled mass of vehicles that’s too long to go through the lock at one time.

The solution? Unbundle. Once in the lock, the first three rows of barges are disconnected. After the gates close on a southbound tow, the emptying valve under the lock opens. The water and thousands of tons of metal and cargo descend 15 feet. The process repeats for the towboat and remaining barges.

Each of those 15 barges can carry between 1,500 and 1,750 tons of dry cargo — enough wheat to bake 2.5 million loaves of bread, or one loaf for every person in Houston. A standard 15-barge tow can haul enough wheat to fill 240 railcars or 1,050 trucks, enough to provide a loaf of bread for every resident of New York, New Jersey and Virginia combined. But the wheat on the barges steaming down the Mississippi is likely bound for Europe or Asia, rather than New York.

BARGES BY THE NUMBERS

Each barge can carry between 1,500 and 1,750 tons of dry cargo — enough wheat to bake 2.5 million loaves of bread, or one loaf for every person in Houston. A standard 15-barge tow can haul enough wheat to fill 240 railcars or 1,050 trucks, enough to provide a loaf of bread for every resident of New York, New Jersey and Virginia combined.

Examples of tow configurations, pushed by a single. A 15-barge tow is standard on the Lower Mississippi River. Click the image to enlarge.

The Western River System, including the Mississippi, Ohio and Illinois Rivers, has been the main conduit for Midwestern crops to travel to international ports in the Gulf of Mexico for export.

INTERNATIONAL GRAINS

Most of the grain grown and transported in the U.S. is used domestically. Of the 480,799,000 tons of grain shipped in the U.S. in 2013, some 114,843,000 tons — 24 percent — was exported, while the remaining 365,956,000 tons remained in the States. Since 1978, the amount of grain transported in the U.S. has steadily increased from about 250 million tons in 1978 to a peak of just over 500 million tons in 2010. But the amount exported has remained steady. In 1978, domestic and export grain was almost evenly split at 125 million tons each. Increased domestic use has been driven by several factors including a growing U.S. population, ethanol producers’ greater demand for corn, and more consumption of grain-fed livestock. At the same time, demand for U.S. exports has been held in check by increased grain production in Brazil, Russia, Canada and the European Union.

In 2013, barges only transported 1 percent of grain used domestically, while trains transported 21 percent and trucks hauled the remaining 78 percent. However, barges shipped 45 percent of U.S. grain bound for foreign markets. Though 2013 marked one of the slower years for grain exports, since 1998 grain exports have remained fairly steady, which is helping keep barge traffic afloat.

Though barges emit fewer greenhouse gases and are more fuel efficient than trains or trucks — barges can move a ton of cargo 647 miles per gallon of fuel while that same gallon will move a ton of cargo 477 miles via train and only 145 miles by truck — barges are confined to waterways wide, deep and regulated enough to handle large commercial tows. These geographical restrictions limit barges’ usefulness in transporting grain to domestic markets. However, it makes them ideal for moving large amounts of grain from Midwestern farms to international ports in Baton Rouge and New Orleans. For years, barges cruising the Western River System (the Mississippi, Illinois and Ohio Rivers) have made it possible for Midwestern farmers like my granddad to help feed the world and make a decent living, most years.

Barges: A Long Legacy

The often-unseen modern barge is a key ingredient of our modern food system. But barges have been a foundational element of modern society for hundreds of years. In the 1400s, an estimated 12,000 grain barges traveled China’s 1,104-mile Grand Canal, which at that time was nearly 1,000 years old.

Copyright: © Vincent Ko Hon Chiu. Photo by: Vincent Ko Hon Chiu http://whc.unesco.org/en/documents/133526

Those barges helped transform China into one of the world’s leading civilizations, transporting the rice, wheat, produce, salt and vinegar that fed the empire while fostering cultural exchange between China’s regional styles of cooking.

In 1666, French King Louis XIV authorized work to begin on the Canal du Midi, a waterway designed to transport wheat from Toulouse to the Mediterranean. As was the case with many early canals, men or pack animals towed the barges — which is why the boats that now push barges are called towboats — loaded with wine and wheat that enriched the merchants of southern France. This canal project helped inspire a boom in 18th-century British canal building, an endeavor that became the backbone of the industrial revolution.

Old map of the Canal du Midi in Southern France.

Across the Atlantic, the young American republic, hemmed in by the Appalachians, needed to find routes westward. Seeing an opportunity, New York capitalized on a gap in the mountains, created by the Mohawk River, and in 1817 began construction on the 363-mile Erie Canal. After the canal opened in 1825, barges were towed by pack animals that trod packed-dirt paths lining the canal’s shore. These barges carried both cargo bound for New York City and passengers heading west — in less than half the time it took to travel the route by wagon and at a tenth of the cost. These efficiencies revolutionized the U.S., transforming New York City into the nation’s leading center of commerce and manufacturing.

The canal made New York the second port, after New Orleans, with an all-water route to the young nation’s interior, opening the West to the eastern seaboard. People and goods manufactured in the East could easily, by early 19th-century standards, travel to the Midwest and start settling there. By 1836, settlers shipped 369,000 barrels of grain back East. Some of their descendants would eventually use barges on the Mississippi to transport grain and other goods to international markets.

Barges may be humble flat-bottomed boats, but as a kid watching them steam up and down the Mississippi I was right to be impressed. They not only helped my granddad manage one of his farms but also helped him and other U.S. farmers transport their crops to countries around the world. Barges have for centuries provided the transportation infrastructure for feeding millions and nurturing modern civilization.

Author

David Leftwich is executive editor of Sugar & Rice, a Gulf Coast food and culture publication, and co-host of The Full Menu, which airs monthly on Houston Public Media’s Houston Matters. He is also the author of the chapbook, The City, published by Little Red Leaves Textile Series. Besides cooking locally grown vegetables and researching the history of food in Houston, he likes to hang out with his wife, daughter, two dogs, one kitten and stacks of books.