On Our Loading Dock

Our nightstands are loaded with books to read and our laptops are packed with websites to explore and unpack some wisdom about the global food supply chain.

Books

Books

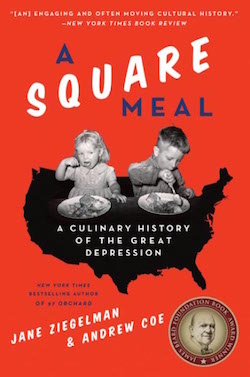

A Square Meal: A Culinary History of the Great Depression

A Square Meal: A Culinary History of the Great Depression

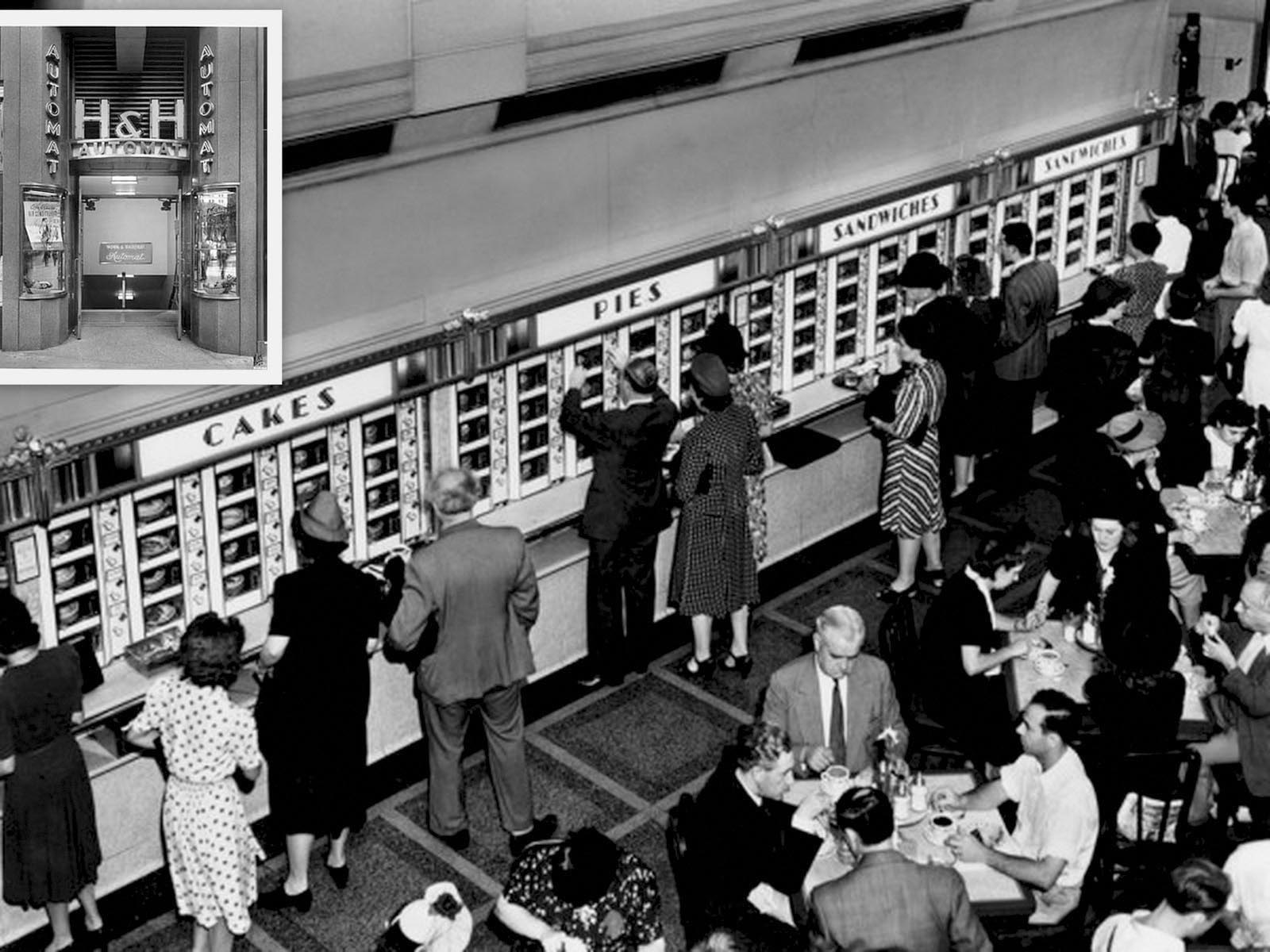

In the 1930s, Americans who were used to abundance were suddenly on food rations. Jane Zeigelman and Andrew Coe show how home economists came to the rescue with nutritional science, and government rose to the occasion with food assistance programs. Alas, some of the food promoted by the government was dismal: liver loaf (made palatable by a the addition of ketchup). Today’s MyPlate guidelines may be unimaginative, at least liver loaf is absent.

Empire of Things: How We Became a World of Consumers, From the Fifteenth Century to the Twenty-First

Empire of Things: How We Became a World of Consumers, From the Fifteenth Century to the Twenty-First

Frank Trentmann examines how and why we consume things, including food. He explains the closed-loop economies of company towns: companies provided jobs, housing and food through one supply chain. He illustrates how two trends — wellness culture and the rise of food prep outside the home — opened opportunities for new food products. Without directly addressing how the global food supply chain gets all those things to consumers, he offers a wide-ranging discussion of why we consume things.

Refrigeration Nation: A History of Ice, Appliances, and Enterprise in America

Refrigeration Nation: A History of Ice, Appliances, and Enterprise in America

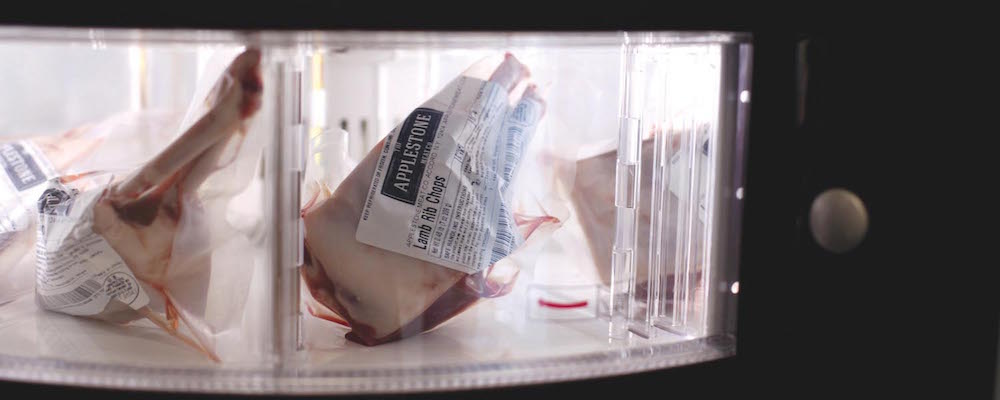

In Jonathan Rees’ history of America’s cold chain, he shows how refrigeration influenced our diets and improved food safety—from ice harvesters in 19th century New England to Kelvinator’s Foodarama in the 1960s (the largest home refrigerator ever built). He explores refrigeration’s impact on the environment, illuminating tradeoffs with technologies that limit food waste by using energy resources. He also suggests ways to make the cold chain more energy efficient.

Grocery: The Buying and Selling of Food in America

Grocery: The Buying and Selling of Food in America

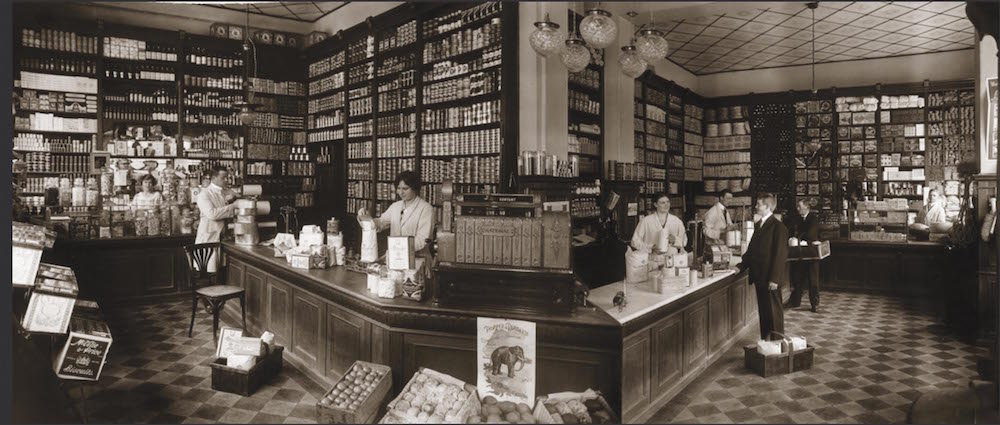

Michael Ruhlman takes readers through the history of food retailing to an evaluation of today’s grocery stores. He explains the complications of processing, labeling and distributing food to a population obsessed with convenience, unable to cook and confused by conflicting food claims. In the end, he shares his view of the future of retailing with consumers who demand more processed food produced on a smaller scale. Look for surprising news about the history of food delivery.

Bread is Gold

Bread is Gold

This new book by the world-famous chef Massimo Bottura contains recipes that address food waste. Dishes created by Bottura and his friends (such as Chef Alain Ducasse) focus on low-cost but tasty ways to prepare meals with minimal waste.

Podcasts

Podcasts

How I Built This

App developer Apoorva Mehta almost gave up on being an entrepreneur until he figured out what he really wanted to do: find a hassle-free way to buy groceries. Five years after launch, the grocery delivery app Instacart is valued at $3 billion.

Containers

Alexis Madrigal covers the world of global shipping in eight episodes. Interviews of tug boat operators and dock workers provide insights into the world of our global supply chain, including the food supply chain. Located in the San Francisco Bay Area, Madrigal captures the sounds of shipping.

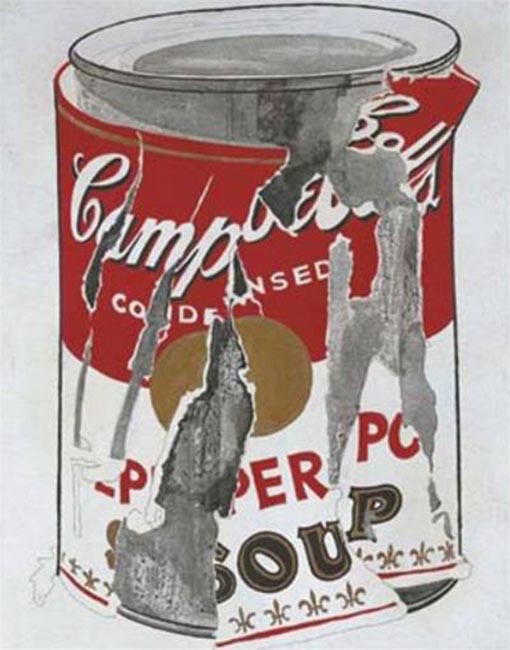

Can Food Waste Save the World?

This episode covers films, chefs and other projects that are raising awareness about the need to reduce food waste.

Films and Television

Films and Television

Wasted

Wasted

Produced by Anthony Bourdain and co-directed by Anna Chai and Nari Kye, this feature documentary film offers more than the usual mea culpa about food waste. Viewers will see mountains of food waste but also learn how high-end chefs are leading a campaign to use everything the world produces. Massimo Bottura, Dan Barber and Danny Bowien are a few of the chefs that make the case for eating food waste. Look for some innovative ways to cook with all those potato peels and ugly fruit. As Bourdain says in the film, “I’d urge you to look at what you’re eating, instead of looking at waste.”

The Oyster Revival

This new documentary film tells the story of how oysters are critical to the ecology of our coastlines. The increasing consumer demand for oysters of all types is adding pressure to the oyster supply and also adding to the number of producers. See how oyster beds are water filtration systems at the same time as they feed an oyster revival.

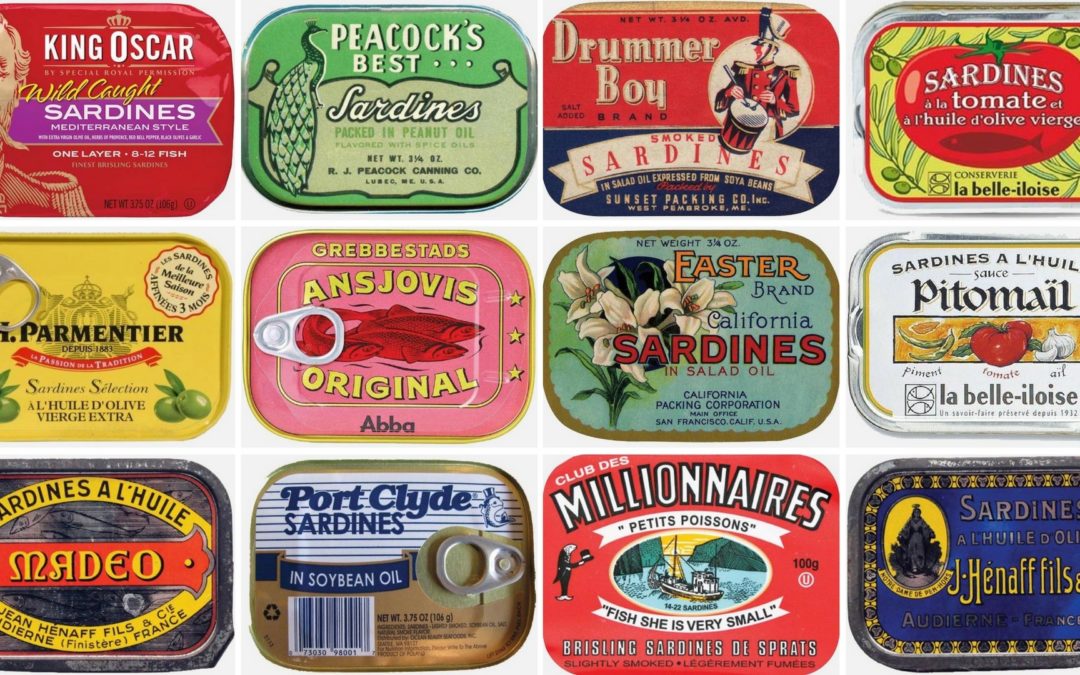

Downeast

The disappearance of fish canneries from our landscape is good news for environmentalists but bad news for those who lose their jobs. This documentary looks at one small town and its loss of jobs and a local fish cannery and how one man attempts to keep the factory open.

Courses

Courses

GustoLab

If you want to study food, there’s no better place to go than Italy and the Gustolab International Institute for Food Studies (GLi). As the first center of study and research in Italy dedicated to academic programs on the theme of Food Studies, GLi offers study abroad programs in food, media and nutrition. Check out their website for academic affiliations that may provide academic credit for Gustolab’s program. While you’re in Italy, enjoy some of the gelato shops featured in the first issue of Food+City magazine.

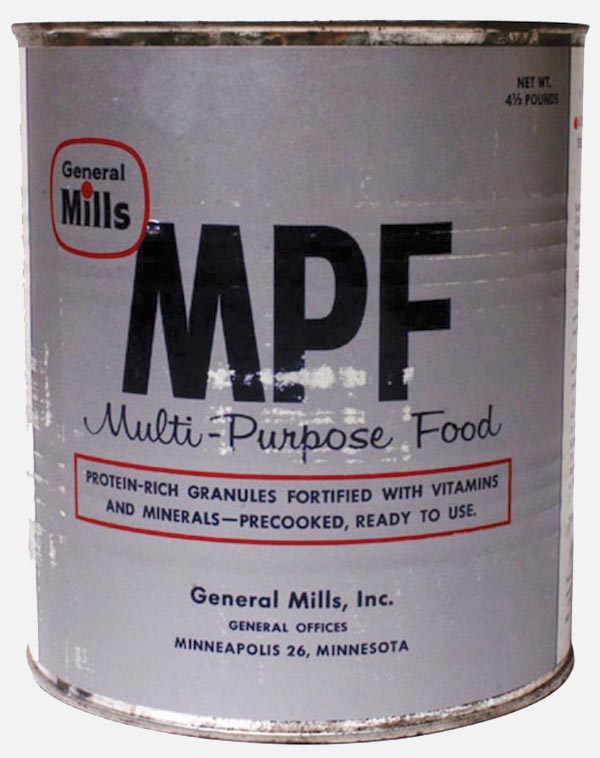

MULTI-PURPOSE FOOD (MPF)

MULTI-PURPOSE FOOD (MPF)