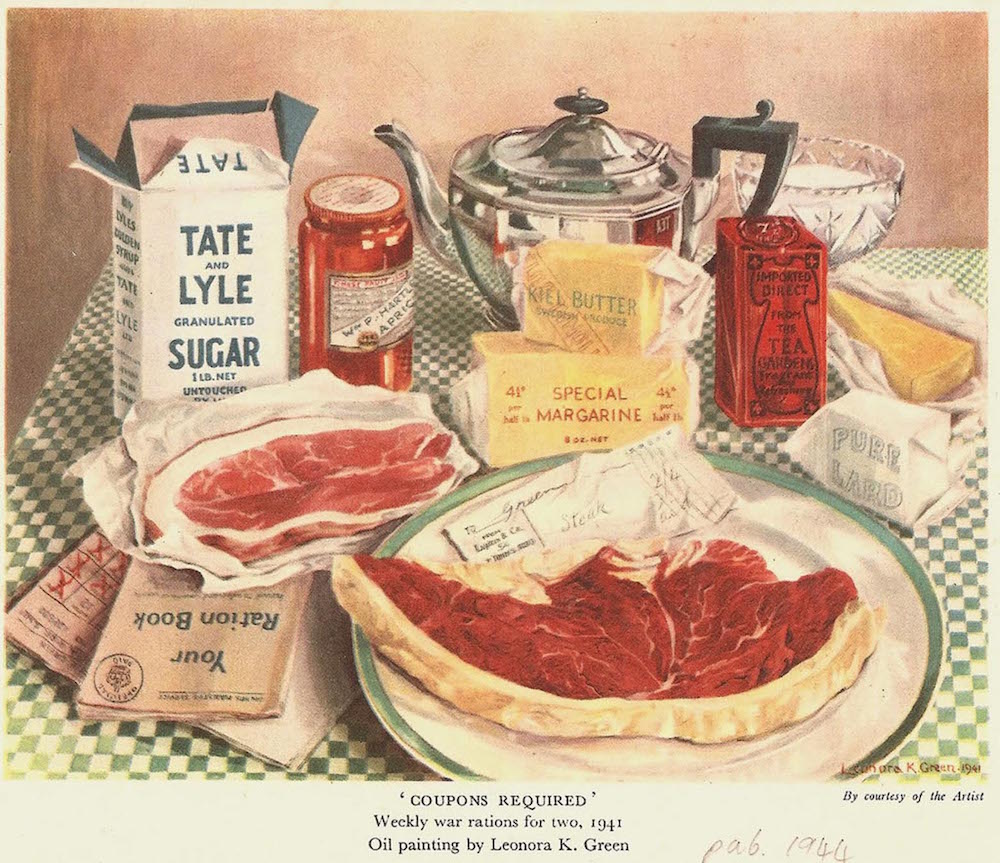

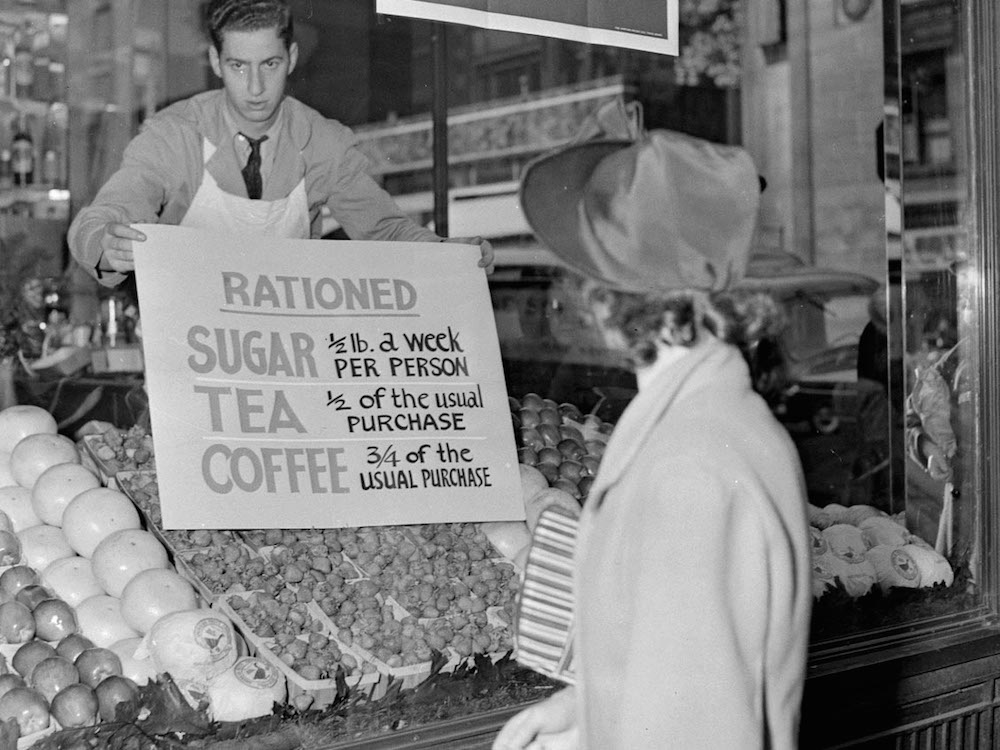

Rations. The word itself conjures up images of shortages, insufficiency and want. No fruit. Limited amounts of sugar and flour. Small bits of tough meat. As World War II interrupted agricultural production and food distribution in the United Kingdom, simple staples — nevermind specialty or exotic items — became scarce.

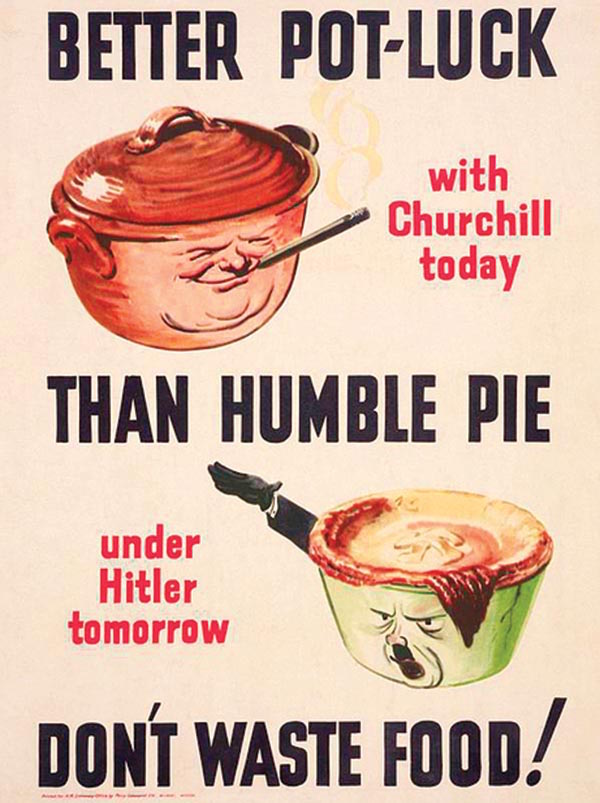

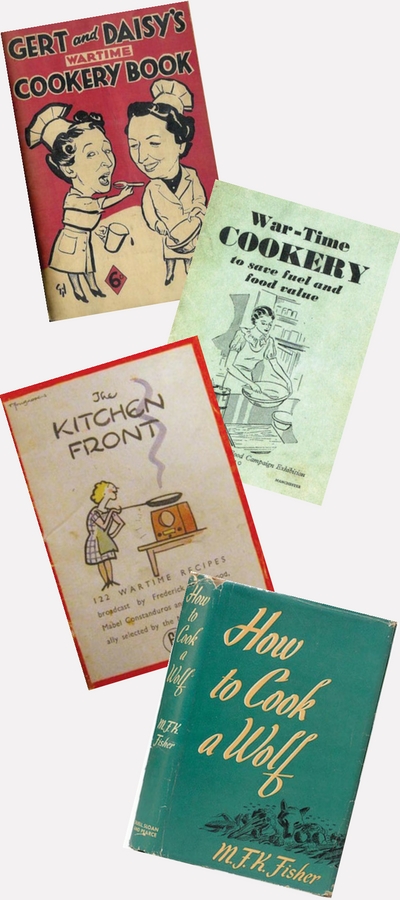

To keep a healthy population that could contribute to the war effort, the British government, like many other governments before it during tough times, instituted a system of controls that limited, but aimed to equalize, what people could buy — regardless of their socioeconomic status. Along with the rations, the Ministry of Food enlisted home economists to help families effectively manage their food budgets. These experts also offered ideas and recipes for making the most of what was available, both in terms of flavor and satisfaction, but also for national morale. Books and pamphlets from the era encouraged home cooks with reassuring language, inviting a patriotic perspective of the hardships.

While long lines were a daily reality at markets, and meats and treats were in short supply, everyone was entitled to the basics. Each citizen had his or her own ration book. Adults were apportioned a certain quantity of meats, fats, sugars, tea, cheese, eggs and milk (either liquid or powdered). Children were allotted their share and enjoyed the occasional orange or portion of whole milk for their growing bodies. Staying healthy was an important part of the war effort.

Other scarce items were distributed through a points system, which allowed consumers some choice and the ability to splurge on fruits, sweets or finer cuts of meat from time to time.

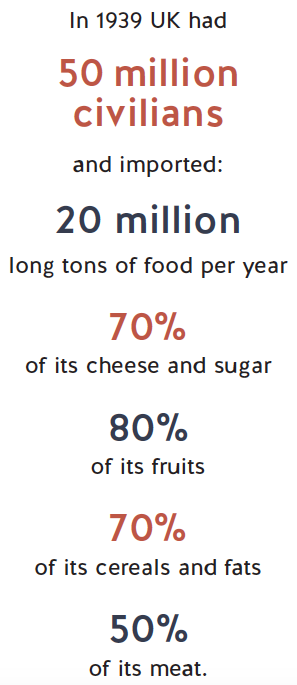

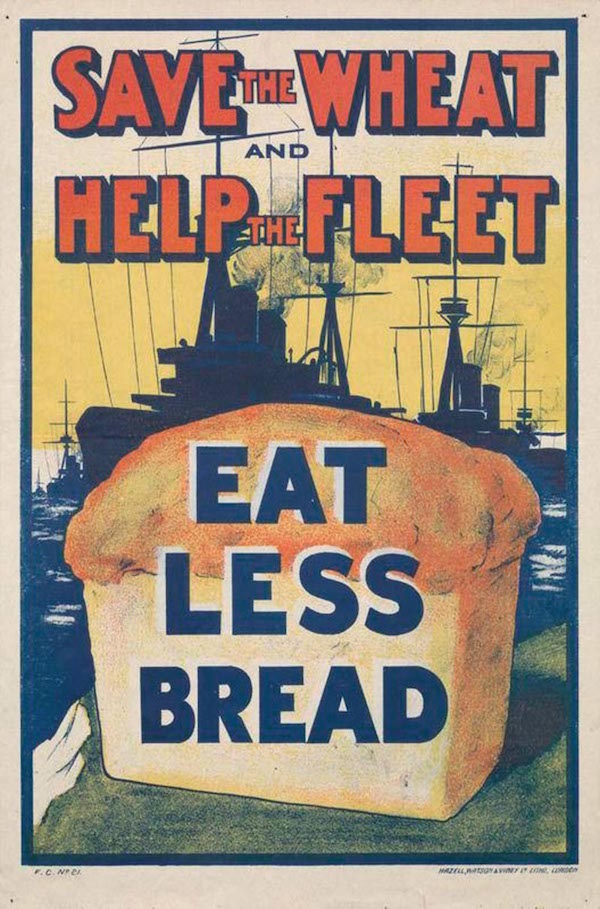

One of the biggest changes during the war for home cooks was the introduction of “National flour.” Before the war, England imported up to 70 percent of its grains (or cereals, as they were known), but the waterways around the island nation were dangerous and not easily passable. German U-boats regularly attacked ships bound for the U.K. in an effort to starve the Brits into submission.

In 1942, the Ministry of Food introduced National flour, a coarser grind that included 15 percent more whole grain wheat than the refined white flour available before the war. It also contained “diluent” grains — including barley, oats and rye — and powdered milk for additional calcium. The government’s goal was twofold: reduce import losses and improve the health of Britons, “even under the handicap of war.”

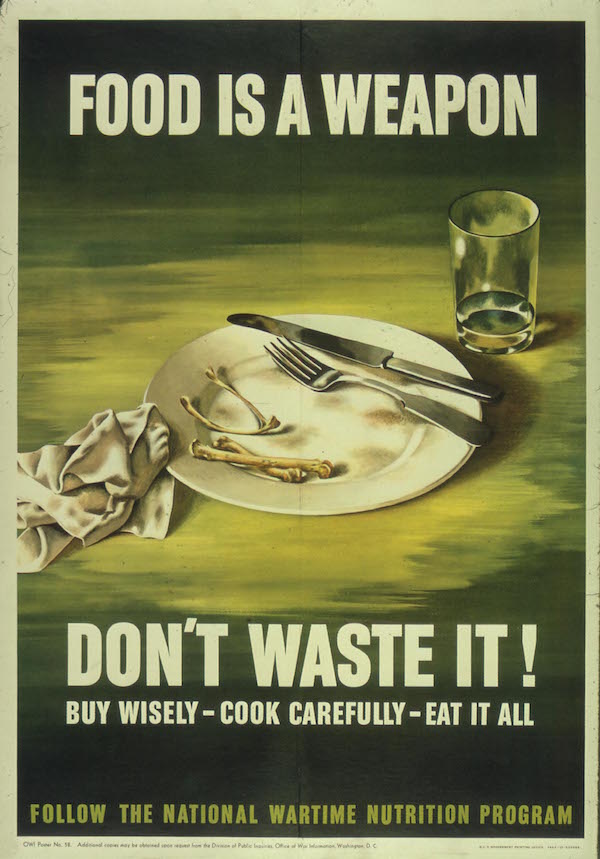

Food-related messaging from the Ministry of Food reminded consumers why they were sacrificing and encouraged good eating habits, despite the hardships.

For a population that loves its baked goods, National flour and the tough, grayish “National loaf” — the only bread available in bakeries — took some getting used to. The Ministry’s home economists published leaflets and newspaper columns with handy hints:

Cooking Hints for National Flour

National flour can be used just as well as white flour in cakes, puddings, pastry, for thickening soups and stews, but remember the following points: —

1. Use a little more liquid for mixing, i.e. mix to a softer consistency.

2. Bake, boil or steam a little longer.

3. Add a little more seasoning to savoury dishes.

4. Add more salt and water when making bread.

5. Use a little extra flour for thickening sauces.

6. Use a little less sugar for sweet dishes.

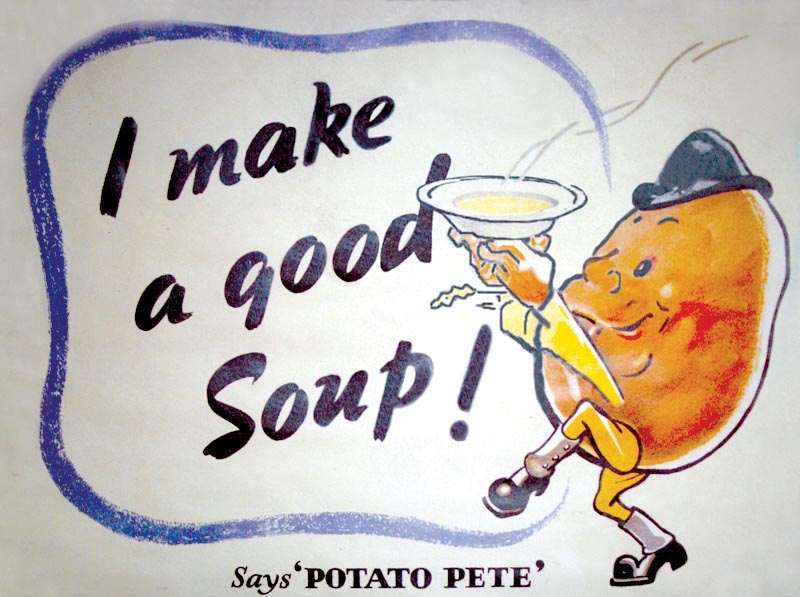

In fact, the Ministry more actively encouraged the use of an alternative and much more readily available ingredient for its population’s pastry needs: potatoes.

Song of Potato Pete

Potatoes new, potatoes old

Potato (in a salad) cold

Potatoes baked or mashed or fried

Potatoes whole, potato pied

Enjoy them all, including chips

Remembering spuds don’t come in ships!

English food bloggers have shared their experiences cooking with wartime rations. And watch a charming newsreel-style film about rations in Britain during WWII.

English food bloggers have shared their experiences cooking with wartime rations. And watch a charming newsreel-style film about rations in Britain during WWII.

The lowly potato was elevated to a key ingredient during the war years. It grew in abundance on the British Isles and was filling during lean years. “Potatoes help to protect you from illness,” says a leaflet from the Ministry of Food. “Potatoes give you warmth and energy. Potatoes are cheap and home-produced. So why stop at serving them once a day? Have them twice, or even three times — for breakfast, dinner and supper.”

P’s for Protection Potatoes afford;

O’s for the Ounces of Energy stored;

T’s for the Tasty, and Vitamins rich in;

A’s for the Art to be learnt in the Kitchen.

T’s for Transport we need not demand;

O’s for old England’s Own Food from the Land;

E’s for the Energy eaten by you;

S’s for the Spuds which will carry us through!

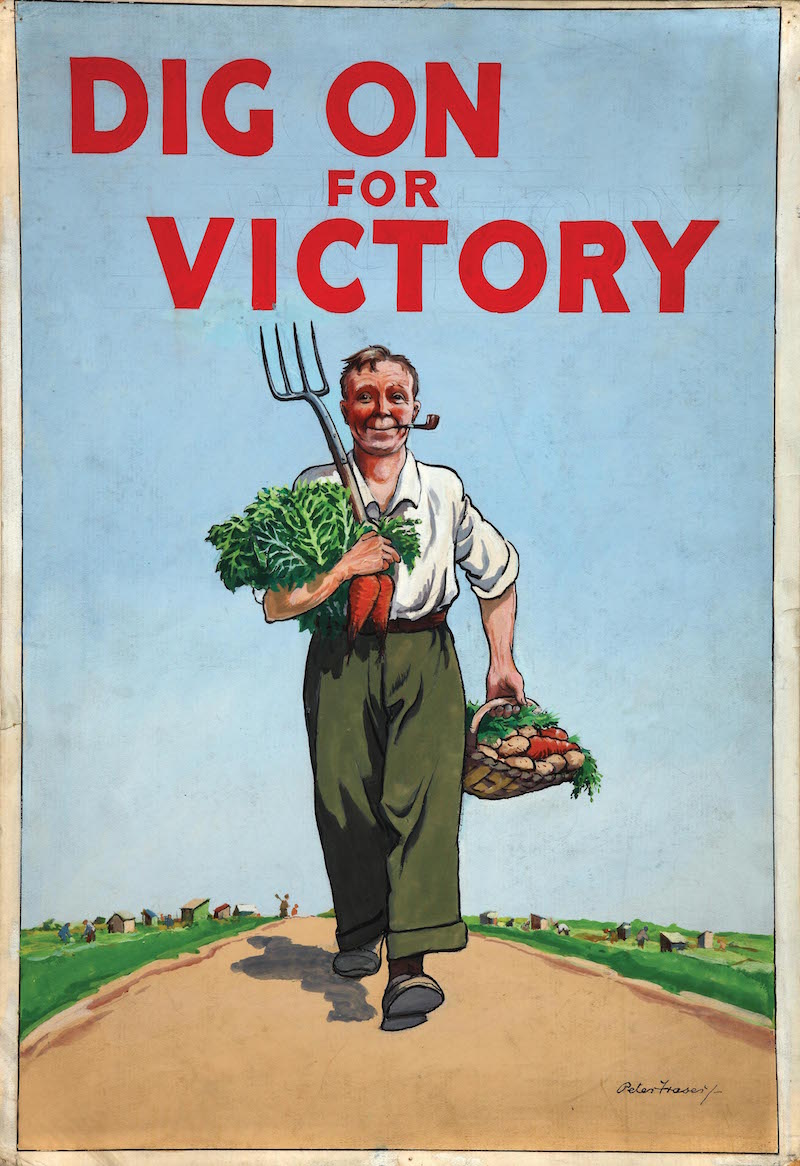

Potatoes were among many edible plants that could be found in British “Victory Gardens.” The government commandeered sports fields and golf courses for planting and encouraged people to use every bit of soil they had access to — from decorative gardens to small edge plots and even containers on apartment rooftops — to cultivate household vegetable and herb gardens. Leeks, turnips and swedes (rutabagas) were popular choices that grew well in the chilly British climate.

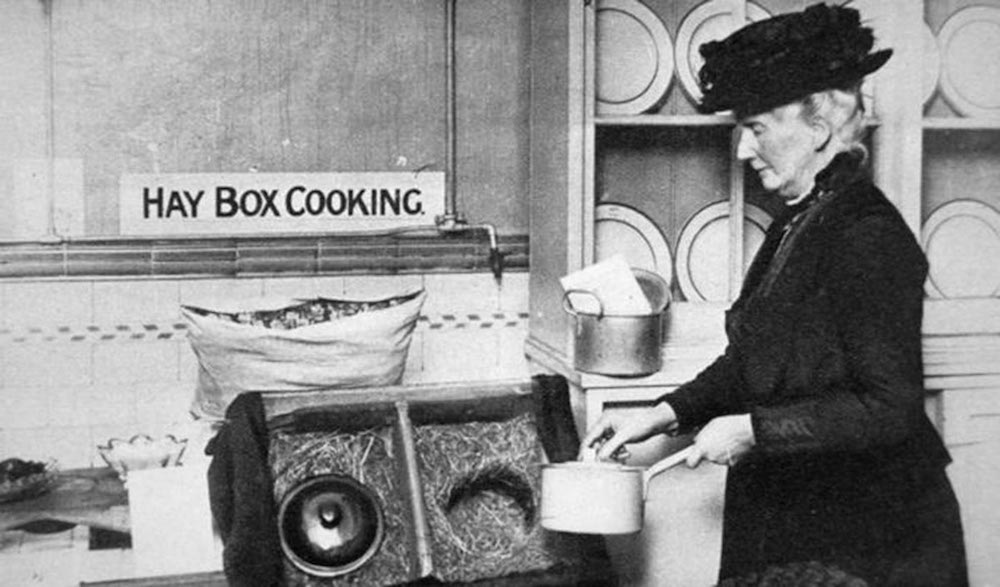

In addition to managing ingredients, home cooks also had to worry about conserving fuel. Using the oven for multiple items at once (the casserole AND the pudding) was crucial. Alternative methods for conserving fuel included starting a braise on the stove, then finishing in a cooling oven once the baked goods were done. Or using a hay box, a box with room for a cooking pot, lined with hay and covered; the insulation preserved the heat in the pot for several hours, until the stew or soup was done.

“More or less, this simple but surprisingly little-practiced rule is true in using an oven: try to fill every inch of space in it,” wrote M.F.K. Fisher in “How to Cook a Wolf,” her handbook of sorts for living happily during trying times. “Even if you do not want baked apples for supper, put a pan of them with whatever is baking at from 240 to 400 degrees. They will be all the better for going slowly, but as long as their skins do not scorch they can cook fast. They make a good meal in themselves, with cream if you have any, or milk heated with some cinnamon and nutmeg in it, and buttered toast and tea.”

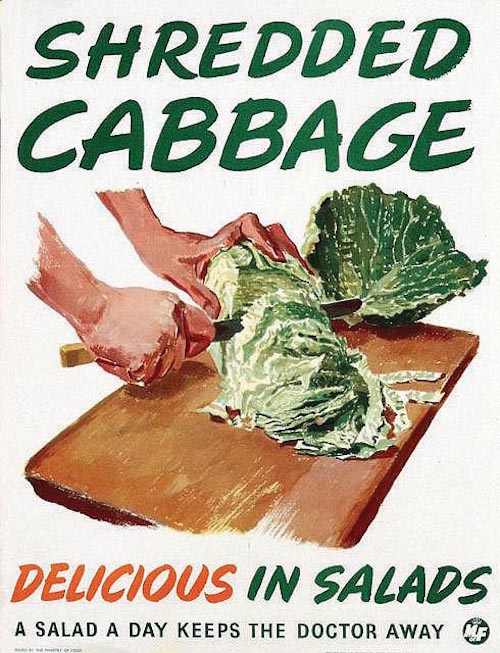

No ingredient was wasted. The water used to boil vegetables was saved for soup base. Leafy stems from root vegetables were neither tossed nor composted but valued as a vegetable in their own right. The Ministry of Food emphasized the nutritional importance of green veggies and encouraged families to eat one raw vegetable per day.

Creative substitutions were common a way to adapt. “You can make many a good tricked dish, with a few mushrooms, some leftover rice, and a dash of wine, if you have one of those frightening, efficient cans of ‘rich brown meat gravy’ on hand,” Fisher writes, inspiring readers to use what they have to its best effect. “It is spurious, maybe. It is chicanery. But it is economical and useful psychologically, especially if you are three miles from a market and the siren blows just as you are pumping up your bike-tire.”

The British system of rations lasted well beyond the end of World War II, ending in 1954. But the effects of rationing were largely positive. “The rich got less to eat, which did them no harm and the poor, so far as the supply would allow, got a diet adequate for health, with free orange juice, cod liver oil, extra milk and other things for mothers and children,” wrote Lord Boyd Orr, post-war head of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, in his memoirs.

The nutritional playing field had been leveled across the classes, and Brits had no choice but to eat their vegetables.

Author

Cory Leahy — editor, writer, runner, enthusiastic cook and veggie-leaning omnivore — has spent more than 20 years as an editor of books, magazines and websites. She recently stepped out of familiar labels and into unknown territory to reimagine a next chapter that’s all about food.