Licking a naturally made gelato in the heavily trafficked city of Rome only takes a few euros. But for its producers, making and moving gelato around Rome is nothing short of miraculous.

Penelope Cruz and her daughter were in Rome last May, and like everyone who visits Italy’s capital city, they wanted gelato.

So they turned to the guy who knows it best, Nazzareno Giolitti, president of the always-buzzing Giolitti gelato shop just steps away from the Pantheon.

Giolitti sat at one of his shop’s coveted outdoor tables, his black polo shirt, white hair and royal blue glasses perfectly matching his blue and black Lucky Strike box. Between sips of espresso and the occasional interruption from his telefonino, Giolitti boasted again and again about the statesmen and actors who visit his shop. Impressive, yes. But he was far less interested in discussing the quotidian set of miracles accomplished by his vast network of purveyors, deliverymen and chefs as they create homemade gelati for more than 2,000 customers a day.

“Rome is a chaotic city. It’s also the most beautiful city, so we pretend not to notice the problems,” he said.

Giolitti’s family started selling gelato in 1906 and opened this location on Via Uffici del Vicario in 1930, making it the oldest Roman gelato shop still in operation. The gregarious fourth-generation gelataio grew up in this elegant cafe, with its high ceilings and white-clad waiters, all of which feel a bit too serious for its clientele.

“It’s difficult,” said Giolitti on running a gelateria in a city with strict traffic regulations and regular strikes and protests. Driving is a real challenge. “But for those born into the chaos, it’s less difficult,” Giolitti explained.

Because Giolitti sells so much product, he receives daily deliveries of milk and eggs from trucks that double-park outside his shop. For the most part, these shipments arrive without a hitch. But when there are impenetrable strikes or heavy traffic, Giolitti gets the call from a frustrated deliveryman. That’s when he sends his motorino out to pick up the product himself.

Once a week, Giolitti drives 30 minutes northeast of Rome’s city center to buy fresh fruit and spices at the Centro Agroalimentare Roma (C.A.R.), the largest wholesale market in Italy and the fourth largest in Europe. The massive 346-acre market in Giudonia looks more like an airport than a place to buy fresh produce.

Each morning, seven of Giolitti’s employees use these ingredients to produce roughly 800 kilos of gelato a day. Most of the gelato is consumed at the shop, but Giolitti also delivers gelato to select restaurants and, if he needs a favor, friends in high places. To transport it, he uses furgoni, or vans sized to maneuver the tight streets of Rome better than the average truck.

“Parking tickets are always a problem,” said Giolitti, “but they are part of the job.” He’s able to keep these 70-euro violations to a minimum thanks to an annual 1,500-euro pass that enables him to move around the city center.

When important statesmen come to town, local officials try to close down Via Uffici del Vicario. Giolitti has to remind them that tourists come from all over the world to visit his shop. They expect it to be open. “So we offer the vigili (traffic police) free gelato,” he said with a smirk.

Giolitti compares Rome’s gelato industry to the tale of its rougher neighbor, Naples: “So many people conquered it and then left,” he said. “The ones left behind, they’re the strongest.”

Giolitti’s old-school approach of selecting produce at the C.A.R. and having milk and eggs delivered daily is too much trouble for the majority of gelato shops in congested Rome. Instead, they spin gelato on site using pre-mixed powders, which can be bought in bulk and have a long shelf life. This also means never having to turn customers away because an ingredient didn’t arrive on time.

“Before the war, gelato was a special treat — you needed access to a cow and you needed really expensive ingredients like sugar, fruit, nuts and chocolate,” said Elizabeth Minchilli, an American expat-turned-Roman food expert who leads food tours around the city. “Once these machines and products were designed, it enabled everyone to make ice cream with the push of a button.”

Minchilli sipped a Negroni and nibbled on peanuts at a trendy bar near her Monti home. The intense, auburn-haired St. Louis native met her Italian husband in her early 20s and settled here, where they raised their two now-grown daughters.

Most of the fruit used in Giolitti’s gelato comes from one of the 85 wholesale produce vendors at the 13-year-old Centro Agroalimentare (C.A.R.), a 346-acre market just outside of Rome that is the largest wholesale market in Italy and the fourth largest in Europe.

Rome’s food system depends on small, nimble methods of transportation, from the furgone truck to the three-wheeled ape and the ubiquitous motorino. Piaggio’s popular Vespa (which means wasp in Italian) is a popular motorino brand.

She explained that a major challenge for Roman businesses is the zona a traffico limitato (ZTL). Rome’s is the largest traffic limitation zone in Europe, meant to keep the historic sites free of pollutants, to encourage public transportation and to reduce traffic.

For the most part, general traffic is restricted from the city center between 6 a.m. and 6 p.m., which causes a rush just before and after, and makes on-time truck deliveries difficult.

But it’s not only the traffic, explained Minchilli. The mayor of Rome is trying to clean up government corruption, but in doing so he’s instigated a “white strike,” where employees do the minimum work required by their contracts.

This means potholes in the roads aren’t being fixed, and if you go to an office to contest a parking ticket, no one is there to help you. “The bureaucracy makes things hard,” said Minchilli.

It’s no surprise, then, that roughly 90 percent of gelato makers are eschewing tradition by using commercially made powdered bases in those push-button machines.

But, as long as that machine is on site, Minchilli said, the gelateria can call itself “artisanal.” This makes it difficult for consumers to know that they’re really eating processed powders.

Gelati made from powders are often overly bright in color. Impressive to look at, but, many argue, not as good as fresh gelato made from whole ingredients.

Overcoming delivery and distribution hurdles while still making ice cream from top-notch ingredients is what prompted Maria Agnese Spagnulo to start her unconventional gelato company, Fatamorgana, 12 years ago.

Maria and her husband, Francesco Simon, realized that in order to use the quality of ingredients they wanted while still selling gelato at a fair price, they needed to create their own economy of scale.

Unlike Giolitti’s traditional model, Spagnulo makes all of the gelato for her seven stores at a commercial kitchen in Trigoria, which is southwest of Rome’s city center and just outside the Grande Raccordo Anulare (GRA), or the “Great Ring Junction,” a 42-mile toll-free highway that encircles Rome.

Spagnulo set up her workspace outside the GRA so that she could easily access her stores within Rome. When you’re within the city, it’s harder to get from point A to point B. But when you can move around the GRA and enter at different points, it’s a lot faster, she explained.

Faster, sure, but this sensible method of distributing one of the freshest gelato products in the city does not qualify as “artisanal” like those powdered packets mixed on site, explained her fast-talking husband.

What customers might not know is just how obsessed Spagnulo is with ingredients. Her gelato base contains only milk, cream, sugar and flavors that come from whole ingredients such as saffron, hibiscus flower and lapsang souchong tea, to name a few. She uses these components to make some unexpected flavors such as Sorrento walnuts with rose petals and violet flowers or chocolate gelato with Kentucky tobacco leaves.

Every day, Fatamorgana’s main kitchen receives a milk delivery from Parmalat, one of the country’s largest dairy companies. For fruits and vegetables, Spagnulo goes to farmers’ markets three times a week to meet with producers. Sometimes she’ll schedule a delivery; other times she’ll carry them back in the company furgone.

For some ingredients, like the prized Bronte pistachios, she orders in bulk directly from a Sicilian farmer. Simon explained, “if the pistachios from Bronte don’t arrive, guess what, we don’t have pistachio gelato that day, and our clients understand that.”

Every day, Spagnulo makes just enough gelato to fill the cases of all seven ice cream shops. At the crack of dawn, two furgone, each fitted with a -22° Fahrenheit freezer cabin, deliver gelato.

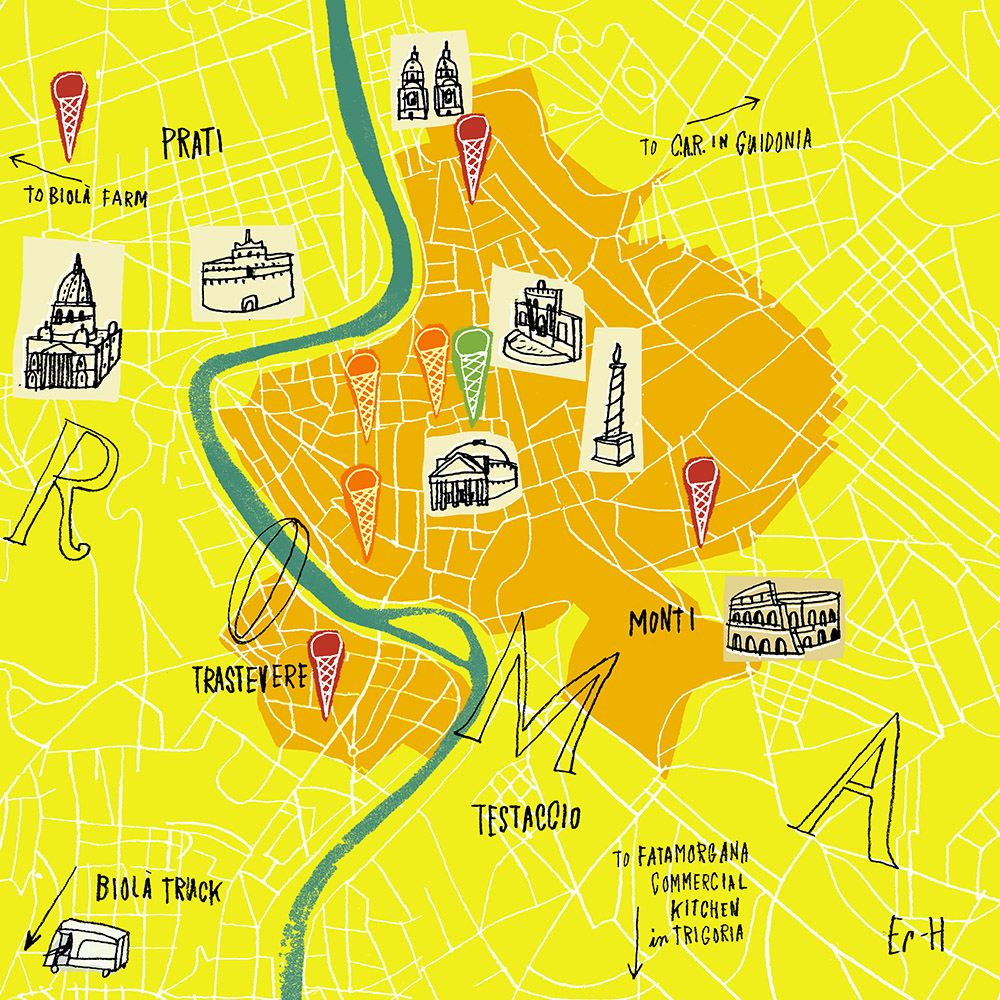

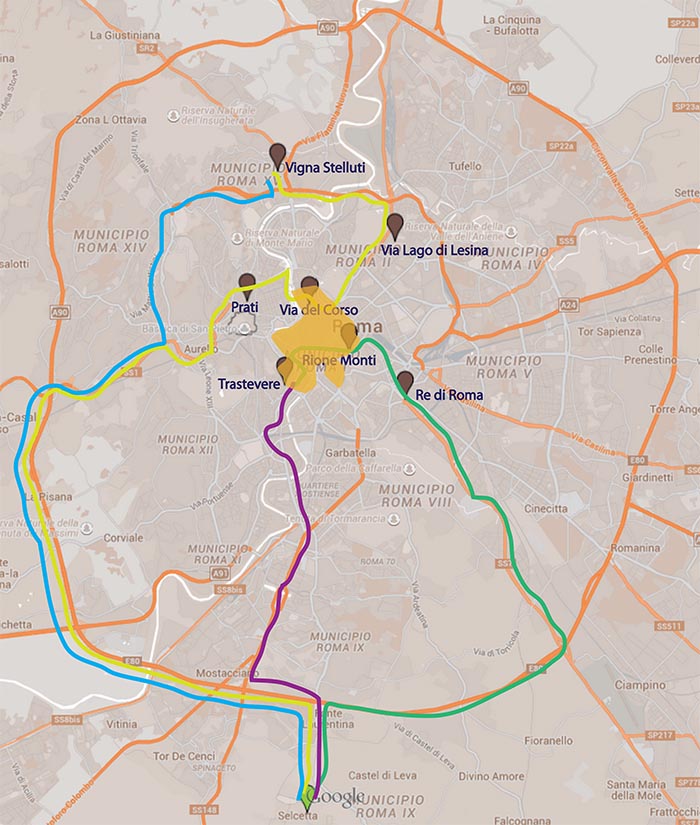

The orange area in the center of the map at left indicates Rome’s ZTL, or traffic limitation zone. Unless you have a special ZTL pass or are a resident you cannot enter this area of the city at certain times, which makes it difficult to deliver goods to shops, markets and stores of all kinds. The green cone is Giolitti. The red cones are Fatamorgana. The orange cones are Grom.

Simon explained that even with a pass to enter the ZTL, delivering gelato to the shops is fraught with challenges. “Before six in the morning, it’s pretty reasonable to get things around Rome,” said Simon. But by the eight o’clock rush hour, “it’s a mess, and from eight-thirty to ten, it’s a disaster.”

A few of their stores are located near 30-minute loading and unloading zones. “But when those are not available, we double park in true Roman style,” Simon said with a smile.

This mid-sized gelateria figured out a profitable model that allowed them to open several stores throughout Rome — so successful they’re discussing the idea of expanding to the U.S.

A gelateria that faces similar challenges to Fatamorgana, but on a much larger scale, is Grom, which has 55 stores in Italy, seven of which are in Rome. Despite their size difference, both companies are reinterpreting how natural gelato can be made, distributed and marketed.

Grom’s liquid gelato bases are all mixed in their Turin production facility from fresh ingredients — high-quality whole milk, as well as free-range egg yolks and many fruits from their own organic farm, Mura Mura, about one hour southeast of Turin in Costigliole d’Asti.

These bases are then frozen and shipped weekly in freezer trucks to their numerous locales. Once the gelato bases arrive at the shop, they are thawed and immediately spun into a rainbow of frozen confections that greet customers by 11 every morning.

Farmer-gelato maker Giudo Martinetti and CEO Federico Grom have grown their business from 19 stores in 2007 to 62 in 2015, including outposts in Dubai, Osaka, Jakarta, Paris, Los Angeles, Malibu and New York.

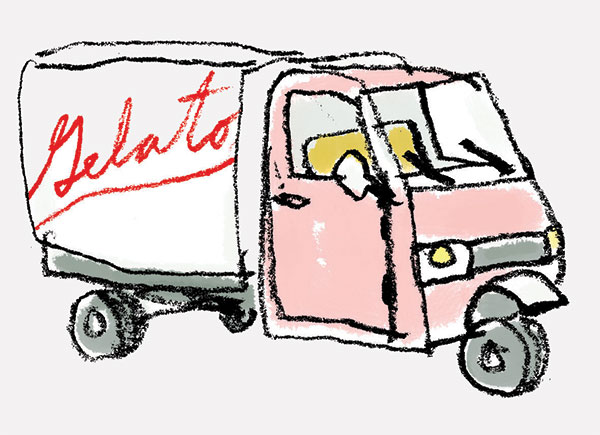

As a result, some of their products have changed to meet the demands of such expansion. When they first opened in 2003, they sourced the famous whole pistachios from Bronte that Spagnulo uses. They’ve since switched to using Tonda Gentile pistachio paste and pistachio flour. Their success, however, has allowed them to launch an organic farm and a bakery that makes homemade cones, a rarity even among the best gelato shops. To get a sense of how this new gelato model works, I squeezed into the company ape (pronounced AH-pay) next to Daniele Piva, a bearded, 20-something salesman.

Ape means “bee” in Italian and refers to the three-wheeled miniature trucks (about the size of a Smart car) that shuttle all kinds of products around the city. Like motorini, apes don’t need permits to pass in and out of the ZTL, which is one of the main reasons that companies like Grom use them to move supplies. Our job was to deliver dry goods like napkins, spoons and cups to the company’s three heavily trafficked stores at the Pantheon, Piazza Navona and Campo dei Fiori.

This was my first ride in an ape, which handles the road more like a Vespa (a moped that means “wasp” in Italian) than a car. We rolled over the uneven cobblestones, dodging the occasional divot in the road and frequent tourist. Motorini and pint-sized cars whizzed past us as we puttered around the twisty roads, crouched in a tiny truck, feeling only somewhat protected from the madness on the streets by thin doors and windows. “You have to have courage to drive in Rome,” explained Piva as I cringed.

Then traffic slowed and brought us to a sudden halt. “In the center of town, the biggest problem is driving around the tourists,” explained Piva, as a group crossed in front of us. Political manifestations and transit strikes usually don’t last for more than a day or two, but they can feel as prevalent as the tourists. “When they happen, you learn to be patient,” Piva said. Unilever, the third-largest consumer goods company, bought Grom last fall, just months after picking up the U.S.-based Talenti. How Grom’s production methods will change under the new ownership is still unclear.

FATAMORGANA DELIVERY ROUTES

The ring road around downtown Rome, called the GRA, helps Fatamorgana deliver gelato most efficiently to its seven stores throughout the city. This map shows the routes their furgone use from their commercial kitchen in Trigoria to their Roman shops and back again. Route #1 (in light green) departs Trigoria Kitchen (a.m.). Route #2 (in blue) returns to Trigoria Kitchen. Route #3 (in green) departs Trigoria Kitchen (p.m.). Route #4 (in magenta) returns to Trigoria Kitchen. Zona a Trafficato Limitato (in orange).

Grom founders, Federico Grom (left) and Guido Martinetti, launched their first store in 2003 with a model that allowed them to control their gelato product but expand exponentially. They just sold their company to Unilever for an undisclosed sum.

Biolà’s grass-fed Jersey cows produce milk, 70 percent of which goes to other dairy companies that bottle and sell it. The remaining milk is sold directly to customers or is made into value-added products.

If Grom and Fatamorgana are trying to make oldschool gelato in a new way, Biolà owner Giuseppe Brandizzi is taking that idea even further.

Brandizzi’s gelato starts at his family’s organic, raw cows’ milk dairy farm just 30 minutes west of Rome, which his grandfather started in 1954 and his father later ran. Today, the third-generation Brandizzi, who considers himself the custodian of his father and grandfather’s philosophies, now runs the farm and Biolà brand.

Over the years and due to its small production, Biolà expanded beyond just milk to sell more value-added products like cheese, yogurt, beef and gelato. Brandizzi only began making gelato a year ago and is hoping to increase production in the coming years due to its popularity and profitability. He can sell a pint for 9 euros.

Biolà differentiates itself further from other gelato companies by selling its products directly to consumers from a mobile freezer-furgone at designated times and locations throughout the week, mostly in Rome’s peripheries. This model was Brandizzi’s creative solution to the Italian law that forbids unpasteurized milk to be sold through a third party.

Unlike his competitors, however, Brandizzi deals with the challenges of raising livestock, producing milk and gelato, and selling the end products. Wearing a plaid shirt and Panama vest with cigarette in hand, Brandizzi walked past his 60 Jersey cows that are the heart of this intentionally small-scale operation. “Cows that are forced to make a lot of milk actually make less,” he explained. “They are stressed and have a shorter lifespan.”

Biolà produces only 500,000 liters of milk annually, which is a small amount compared to the 10 million liters that the nearby Maccarese dairy produces each year. Of that 500,000, 70 percent goes to other milk companies that bottle and sell it. The remaining 30 percent goes into their direct sales of milk and those value-added products.

Anywhere from one to three furgoni drive to various locations each day, making about three to four stops and parking in a locale for a few hours at a time.

Gerardo Della Vecchia, a jovial, rotund man in his 70s who has been working for Brandizzi for 10 years, parked his Biolà van along the busy Via Gianicolense in the Monteverde district just southwest of the city center.

Della Vecchia set his credit card machine on a small wooden table that hung over the passenger side door and opened the truck’s sliding door to reveal the milk dispenser — a mini door that led to the truck’s refrigerator unit. The sign above the dispenser said the milk had been milked at 4 a.m. that morning and should be consumed in just three days.

By 4:30 p.m. the first motorino pulled up. Helmut on, the driver yanked an empty bottle from his miniature trunk and handed it to Della Vecchia, who filled it with fresh milk. Most of his clients knew him by name. “I watched this kid grow up,” he said, after a teenage boy turned to leave with a bottle of milk.

A young woman, who looked as though she had just come from the beach, bought a small cup of hazelnut gelato. It was clear that Della Vecchia had a good rapport with the nearby café, whose owner came out to chat. But for some Biolà salesmen this isn’t always the case. “Sometimes nearby shop owners call the police, and tell us to move on,” Brandizzi said. But when the municipal police arrive to ticket, that’s when he gifts them some fresh ricotta or gelato.

Brandizzi may not serve his gelato to movie stars or heads of state, but as he talked about currying favor with local officials, he wore a smirk similar to Giolitti’s when he described how he makes Rome’s complicated, often messy and maddening, food system work for him. Call it what you will — these little miracles make the world, and gelato biz, run.

Author

Jill Santopietro is a food writer, cooking instructor, food stylist and recipe developer-tester with a master’s in gastronomy from Boston University. She spent six years as a columnist for The Boston Globe food section and worked as a chef for the PBS show, “Simply Ming.” She is somewhat obsessed with anchovies and ice cream (just not together).