A century after the Panama Canal opened, Panama is opening a second set of locks this year that will welcome some of the world’s largest ships. This globe-changing expansion has U.S. farmers celebrating and port officials scrambling, but what does it mean for your plate?

In 2006, the Panama Canal had a problem.

Researchers predicted that by 2012 the canal would be maxed out. The 48-mile-long series of locks, an industrial miracle nearly forgotten by most of the people who benefit from it, would either have to turn ships away or raise prices to decrease demand. Panama’s President Martín Torrijos proposed an expansion of the canal, and in 2007 it began. That’s where our story begins, sort of.

America’s demands for growth — and for fresh food from the other hemisphere — shaped the canal as much as the canal has shaped Americans. Teddy Roosevelt’s brash international ambitions brought the canal into life, which in turn encouraged a century of accelerated consumption and a need to expand the domestic infrastructure to support it. These networks and consumption patterns underlie what foods we see in our supermarkets and how much they cost.

This year, the canal expansion will finally open, but most customers won’t notice anything different in their grocery cart. Why? Because when it’s working, infrastructure is invisible. Water, electricity and food flow in and out of our homes, but we don’t often consider how the links of the supply chain rely on each other. What happens when one of those links doubles in size?

CONNECTING THE OCEANS

Around the time gold was discovered in California, Frenchman Ferdinand de Lesseps secured permission to build a canal from the Khedive of Egypt in 1854. Construction on what became the Suez Canal began in 1859 and lasted just over 10 years. On the heels of completing the project, Lesseps began to eye Panama.

It took more than a decade, but by 1881 Lesseps had raised funds to build a sea-level canal. He underestimated the time and funds needed to complete the project, but even more daunting were the increasing deaths of his workers who fell ill and died faster than he could replace them. Still not known to transmit disease, mosquitoes were rampantly spreading yellow fever and malaria. By 1884, more than 200 men were dying every month.

Eight years after work began, all the money, more than 1.2 billion French francs, was gone. The project continued on life support until a suitable buyer was found. The asking price: $109 million U.S. dollars. But France was in a bind. They’d sunk hundreds of millions into their failed canal attempt and were still losing cash and workers as they attempted to slow the deterioration of machinery and excavation. The price tag left them with few options for buyers. The United States was an ideal prospect but had leverage — investing in a second canal route that had been found in Nicaragua. When the U.S. put in the lowball offer of $40 million, France had to take it.

The U.S. formally began its canal effort in 1904. By then, officials knew that mosquitoes were the root cause of many illnesses and had access to some preventive medicines. With a more stable workforce, the man running the project, John Frank Stevens, could solve the other major problem: how to build a canal that didn’t require removing millions of tons of dirt. Instead of a sea-level canal, he petitioned for a lock system on two sides of a man-made lake. Each lock would fill with water and empty itself to raise or lower a vessel.

Engineers built Gatun Lake, an artificial body of water 85 feet above sea level, and constructed the three locks on each side to manage the water level as ships passed through the main cut. In 1914, a thousand ships would navigate the canal locks. Nearly a century later, over 14,700 ships traversed the canal per year. Now, during the high season, it is not uncommon for vessels to wait 10 days before transiting the canal. It can cost shippers as much as $50,000 per day to sit idle, stymied by a complex bidding system for a slot in the canal.

The new locks, opening this year, are wider and run parallel to the current locks. The locks allow for ships that are 51 percent wider and 24 percent longer, which translates to 177 percent more containers per ship. Currently the project is $1 billion over budget, with estimates placing the total expansion cost at about $7 billion, about 20 percent of Panama’s. Though the canal expansion has only just been completed, Panama is considering a second expansion to build a fourth set of locks. Estimates put that project in the range of $15 to $20 billion.

The impact of this current expansion can only be imagined. About 55 percent of U.S. agricultural products are shipped through the Panama Canal. After the expansion, up to 80 percent of those products are expected to be shipped through that waterway. More grain passes through the canal than any other item or good. It’s difficult to calculate just how much the new canal will influence food prices, in part because the cost of fuel makes up half of a ship’s operating costs and bigger ships require more fuel to move. Whatever the outcome with regard to prices, it is likely that consumers will enjoy a wider variety of food ingredients as greater capacity will enable a more diverse food supply.

But the increased capacity may not be fully utilized until the global economy gets back on its feet. In 2015, shippers began seeing the impact of erratic movements in world currencies and the lagging economies of developing countries. This slowdown in global economic growth caused large shipping companies such as Maersk to cut back on plans for building new container ships. Stockpiles of empty containers sitting at ports without food to ship also signaled a dampening of hopes for full utilization of the canal expansion.

A wider channel and second set of locks that can accommodate post-Panamax ships now run parallel to the existing Panama Canal. These are the Miraflores locks, the closest to the Pacific. Image by Mike Kelley.

The Panama Canal took more than two decades to complete, including nine years to dig out the 9-mile-long Culebra Cut, which crosses Panama’s continental divide.

Skipping the Line

In 2006, a British oil tanker paid $220,000 to jump ahead of 83 other ships.

BIGGER AND BETTER

The new locks allow for ships that are 51 percent wider and 24 percent longer. This translates to 177 percent more containers per ship.

AN INTERSTATE HIGHWAY SYSTEM IS BORN

Forty years after the Panama Canal was completed, another globe-changing link in the shipping infrastructure came to life: The U.S. Interstate System.

After the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration spent $4 billion (nearly $68 billion today) building and improving roads from coast to coast. With asphalt below the tires, the trucking industry started to take root, and by 1956, President Dwight D. Eisenhower authorized the interstate highway project that now encompasses 47,856 miles of road. Since the 1960s, the number of 18-wheelers has increased from fewer than than 1 million to more than 3 million, and the number of registered vehicles from 74 million to more than 255 million now.

After the highway system opened, intermodal shipping expanded quickly, but we were still missing one key piece, which would neatly link how we moved freight across both land and sea: the shipping container.

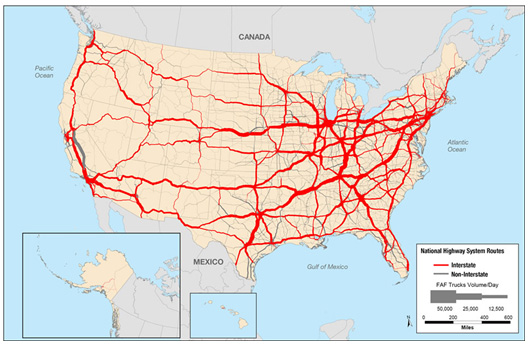

Average daily long-haul traffic on the national highway system in the U.S.

THE TWENTY-FOOT EQUIVALENT UNIT

At the same time as Eisenhower signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act, a shipping entrepreneur saw the possibilities of combining trucks with ships. Malcolm McLean, the founder of a small trucking company in North Carolina, sent the first modern cargo ship out to sea. He had converted two World War II tankers to carry removable containers. In the mid-1950s, he created the first container ship, Ideal-X, which transported trailers stacked above and below decks. Eventually, he built the Sea-Land Company and created shipping containers that were loaded on and off ships and transported to and from ports on trucks.

The large containers McLean developed are called TEUs — twenty-foot equivalent units — after the containers’ measurements. TEUs can move far greater quantities of goods than moving cargo one piece at a time into a ship’s hold, a long-used method known as break bulk. Today, there are more than 20 million active TEUs, and 90 percent of the things you purchase, including food, have spent time in a shipping container. According to Rose George, author of “Ninety Percent of Everything,” many of the largest container ships have the capacity to transport one banana for every person in Europe.

The modern intermodal system — moving containers from ships to trucks and back again — brought us more food at less cost. But it also resulted during the last century in unintended consequences, such as once-diverse agricultural regions shifting toward monoculture and commodity farming.

Once the full intermodal system opened up, the American diet, though more diverse because of an increased variety of food being transported, started to become standardized. The food sold in a grocery store in one part of the country looked a lot like the food sold in every other part of the country, but few people realized that infrastructure was what was shaping their diet.

BIGGER BOATS, BIGGER PORTS

As more containers came into circulation, an interesting trend began to appear. Instead of building more ships, companies were building larger ships. For the companies, this meant significant cost savings. For the canals and ports, it was one never-ending (and expensive) nightmare.

Without much regard for existing infrastructure, ships have continued to balloon in size, and if they can’t fit through one canal or port, they are then routed to another port that can accommodate them, creating a fairly tidy demonstration of supply and demand.

This competition has led to intense spending across the world to accommodate ever-growing cargo ships. Ports are dredging land under water to create deeper channels to the docks. They are buying larger cranes and investing in automated technologies, including driverless vehicles called AGVs (Automated Guided Vehicles) and automated straddle carriers that can move containers around a terminal. Some ports, like the one in Portland, Oregon, are struggling to stay profitable because they can’t keep up with the growth of the ships.

Likewise for canals, there’s a very real urgency to update because they feel the pressure of competition too. Though it’s convenient, a ship doesn’t have to take the Panama Canal. Those coming from Asia to the United States can go through the Suez Canal, which completed its own expansion in 2015, adding a second shipping lane and deepening the existing one to allow for increased traffic and larger ships.

The Suez Canal isn’t the only other option for a shipping company. Melting ice has led to the development of arctic shipping lanes, and all eyes have been on Nicaragua, where a second Pacific-Atlantic canal is in the works. A slump in the Chinese economy has slowed the development of the canal, spearheaded by Chinese billionaire Wang Jing, but if the project can regain momentum, it will represent one of the largest earthmoving projects in history, employing 50,000 people. For context, the Panama Canal is 48 miles long, 15 miles of which is Gatun Lake. If the Nicaraguan Canal is completed it will be 170 miles long, with 66 miles on Nicaragua Lake.

When Panama saw its capacity ceiling approaching and ships widening, authorities made the call to add a third, wider set of locks. Almost immediately, ports, especially along the Eastern seaboard and Gulf Coast, began planning the improvements they’d have to make to attract more traffic.

The Port of New Orleans spent nearly $40 million to expand container handling capabilities, according to Director of External Affairs Matt Gresham. As reefer technology has improved, so has the demand for storage of these refrigerated containers. The Port of New Orleans spent $7.9 million to build a container racking system that can store 600 refrigerated containers, many holding imported bananas or poultry ready for export.

The Port of Miami is also hustling to attract the big ships. Last year, the port completed a dredging project that deepened the port by 50 feet, which allows them to service ships up to 22 containers wide. With this kind of volume, the Miami port is poised to become the primary entry point for products from South America, which would then be loaded onto trucks and distributed across the country.

These expansions are well-grounded. The Panama Canal expansion is going to unlock a huge amount of volume with roughly the same number of ships.

But the canal expansion and port renovations are still not enough for ships like Maersk’s Triple-E class and several Mediterranean Shipping Company vessels, which are among the largest container ships in the world. In 2014, the China Shipping Container Lines launched the CSCL, a container ship with a capacity of more than 19,000 containers. These newer, larger ships can load more containers, travel faster, and provide greater fuel efficiency. Bigger ships mean bigger capacity, and it’s easier to build a bigger ship than to dredge a port or expand a canal.

Farmers in the U.S. have also been pushing for port renovations and canal expansions because they know those changes to the supply chain infrastructure will mean more buyers for their goods. In 2011 China moved ahead of Canada as the largest importer of U.S. agricultural products. During 2012–2013, the U.S. provided almost a quarter of all agricultural imports to China. A significant percentage of those imported agricultural products are grains. The canal expansion is of particular interest to companies facilitating the shipment of those grains from the Midwest, where many of them are grown. And it appears that most developing countries will be net food importers due to rising incomes, lagging infrastructure and agricultural practices.

REEFER SHIP

A reefer ship is a refrigerated cargo ship; a type of ship typically used to transport perishable commodities which require temperature-controlled transportation, such as fruit, meat, fish, vegetables, dairy products and other foods.

LABOR DISPUTES

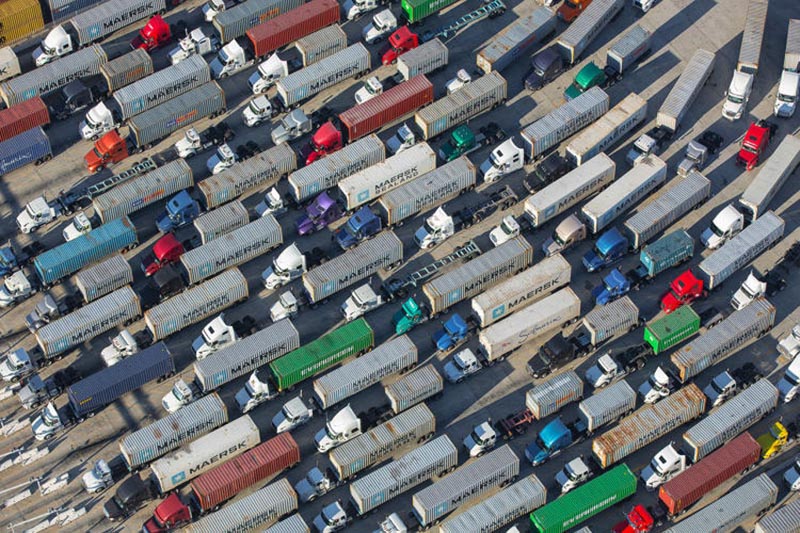

Labor disputes frequently bring intermodal shipping to a halt. In early 2015, dockworkers practically shut down nearly 30 ports along the West Coast of the United States, leaving dozens of cargo ships stranded all up and down the seaboard. This didn’t only mean that goods, including perishable foods, were floating offshore: It also meant that U.S.-grown food was rotting while waiting to be picked up.

The 2015 dockworker labor dispute forced a backlog of trucks at the Port of Los Angeles, where hundreds of trucks and dozens of cargo ships waiting to pick up and unload freight. This port, along with the port in Long Beach, handle more than 40 percent of goods entering the U.S. and almost 30 percent of its exports. Images by Mike Kelley.

EXPANDING A TASTE FOR GLOBAL FOOD

Expanding the canal will shift where ships dock, but it won’t shift our palate or our consumption levels, experts say. America has plenty of food. We import food because we like variety and we demand it all year. Not long ago, finding a fresh pineapple during a Minnesota winter would have been a miracle, but now, you can find plenty of them on produce shelves just about every day of the year.

The expanded canals will increase this kind of globalized eating in other places in the world. Asia’s consumption habits, for instance, have changed tremendously in the past 20 years, with per capita consumption of rice decreasing and consumption of wheat, protein and convenience food and drinks on the rise.

In building the interstate to unify the country, we created immense opportunities for trade while implicitly encouraging product standardization and the dissolution of regional mainstays. Ten general stores have given way to one central Walmart. States have become known for farming only one or two commodities. The same gas station burritos are sold along all 2,460 miles of I-10. These things aren’t inherently bad — except for the burritos — but they represent a shift in cultural values made possible by expanding infrastructure.

We’ve seen the interstate system revolutionize how we grow and transport food. We’ve seen reefers, shipping containers, ports and canals guarantee a consistent supply of produce from tropical countries. Alternatively, we’ve seen the food we have grown and the diet we created packaged up and exported to other countries through those very same channels.

Time will tell exactly what happens after the third locks — and maybe the fourth — open in the Panama Canal, and whether the Chinese-built Nicaraguan Canal, if completed, will turn everything that we know about canal economics on its head.

The Panama Canal expansion won’t show up on the average American consumer’s grocery receipt. The cost savings will be eaten up by shipping companies, and though your mango may arrive a day earlier, you won’t know it. That’s the way it’s supposed to be, but with our growing interest in food and where it comes from, maybe we’ll demand more transparency from a system that thrives on invisibility.

Author

Craig Cannon is the coauthor of The Container Guide, a field guide to shipping containers and the corporations that own them. He helps run the Infrastructure Observatory and also organizes Comedy Hack Day, an event series where software developers and comedians build apps together.