Combatting “fish fraud” and ensuring sound fishing practices are two reasons net-to-plate tracking is on the rise. But high-tech tracing satisfies consumers’ curiosity, too.

Does it matter if your sashimi is not the fish it purports to be — or that your salmon was grown on a farm in Ireland, but labeled wild-caught from the Pacific?

When amplified globally, the answer is a resounding yes. In the last few years, DNA analysis of seafood samples from markets and restaurants has helped expose the prevalence of “fish fraud.” Many industry insiders assert that combating the problem hinges on one thing: end-to-end traceability.

A BOATLOAD OF RULES

Management of fisheries has been a long-standing practice. The Venetian Republic, for instance, enacted protective laws as early as 1173, taking the view that the Venetian lagoon and its resources were the critical underpinning of the Venetian economy. In the mid-20th century, global industrialization of fishing led to stock depletion in U.S. waters and ushered in the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (1972; revised 1996). This legislation created a complex quota and landings reporting system to manage and monitor the harvest.

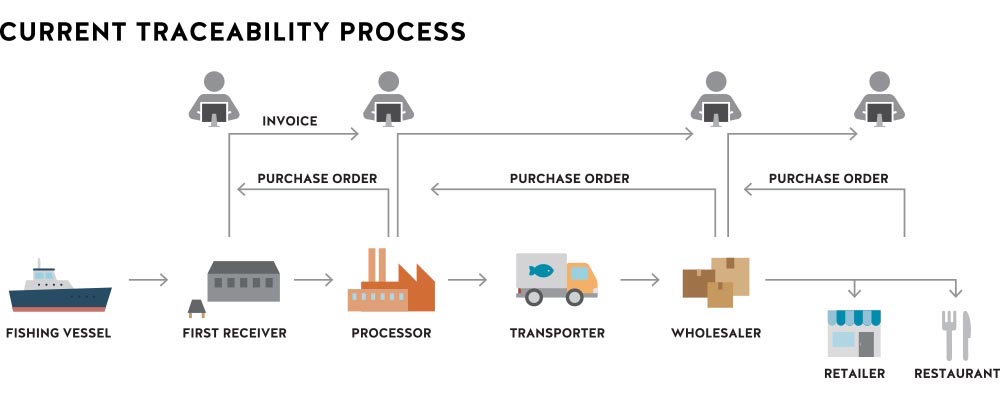

Separately, health and safety laws for handling food products in processing, transport, and at point of sale leave their own paper trail. Bringing the records from the two ends of the supply chain together into an integrated system is more complex than it might seem, but new technology is helping to make this possible.

CERTIFY THY FISH

Much credit goes to non-governmental organizations (NGOs) for raising awareness about the state of the commercial seafood industry. In the 1990s, the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) was formed to protect the world’s oceans by working directly with the seafood industry, encouraging best practices among all participants in a fishery. Companies that meet MSC criteria can carry the blue MSC ecolabel on their products and in branding. The MSC Chain of Custody Standard applies to all suppliers, processors and vendors handling MSC-certified seafood, and MSC performs periodic auditing to verify those standards are being followed.

Most major supermarket chains now require that the fish products they buy have an environmental certification or be associated with a Fishery Improvement Project (FIP). Yet problems persist. Continuing concerns over illegally harvested and mislabeled seafood, as well as human rights abuses in the seafood industry, led to the founding in 2002 of FishWise. The NGO now leads the charge for electronic, interoperable systems for end-to-end traceability that implicate all players in the commercial seafood supply chain. In 2014, President Obama issued an executive order to combat illegal unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing and seafood fraud.

This brought about a new traceability program for imported fish and fish products especially vulnerable to IUU fishing and/or seafood fraud, with a compliance deadline of January 1, 2018. Additional legislation on the federal and state levels may follow, in part as a protective measure for one of the country’s oldest industries.

INNOVATION IS ON THE MENU

As the hub of the New England commercial seafood industry, Boston is a rich testing ground for innovation in seafood traceability and tracking across the supply chain. Seafood restaurants and retailers have been particularly adept at responding to consumers’ concerns and capitalizing on growing interest in food production. For example, menus at Island Creek Oyster Bar and Row 34 list not only the name and place of origin for each shellfish offering but also its producer. Giving previously undifferentiated products, such as oysters, a provenance is a first step in building brands and customer affinity.

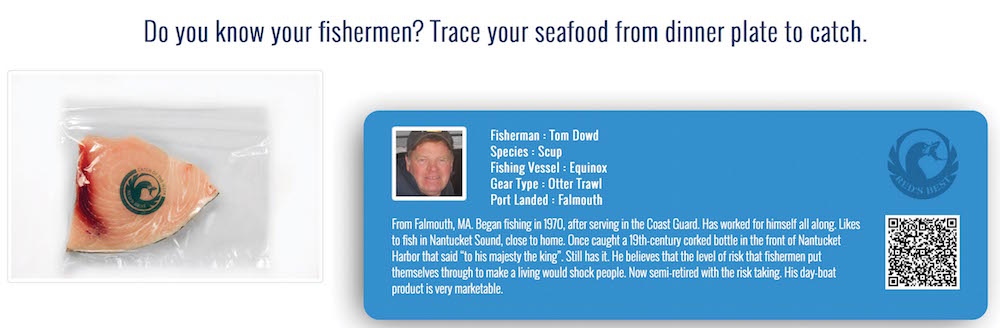

Based on the idea that consumers care about the source of their fish as well as the livelihood of the New England fishermen who provide it, seafood company Red’s Best has developed a traceability program for the products it sources and sells. Labels include QR codes, readable with smartphone apps, linking customers to information about where and how the fish was caught and about the life of the fisherman who caught it. On the tracking front, Maine Coast Lobster, which ships live lobsters globally from Boston’s Logan Airport, places sensors that record time, temperature and humidity within its specially designed shipping boxes. If a problem is detected upon arrival, data can be uploaded via USB and correlated with logistics records to pinpoint the problem in the transport process.

MOVING FORWARD WITH BACKTRACKER

Launching one of the most fully integrated solutions is BackTracker, the Boston-based startup with a data-driven seafood traceability system to eliminate operational errors and bad practices that can occur at any number of steps along the supply chain. Founder and CEO Michael Carroll is a former commercial fisherman who obtained a graduate degree in economics before becoming a fish buyer for a major supermarket chain and then working on fishery certification. He understands the commercial seafood industry, including its eccentricities, in a way that few people do. BackTracker accesses official government harvest records and uses them for an important secondary purpose: following the records through each participant in the supply chain — first receiver, processor, wholesaler and retailer — and verifying participant-provided output data at each step.

“If a landing record lists 10,000 pounds of haddock from a particular vessel on a particular day, and we know that haddock has a 36 percent yield when processed, we shouldn’t see more than 3,600 pounds of haddock tied to that landing from the processor,” Carroll explains.

As anyone who has watched an episode of “Wicked Tuna” knows, the fishing industry is a competitive business. While GPS technology makes it possible to collect data about where fish are being caught, for now traceability begins with what is reported at the dock.

In this context, unbiased third-party certification has its advantages. All data is encrypted and ownership remains with the parties who provide it. BackTracker issues unique tamperproof codes as records of verification for each individual package in a processed lot, and the app for managing the process is flexible. “Trade partners can determine collectively which information is shared downstream and which is kept confidential,” Carroll notes.

BackTracker’s pilot system is now underway in Boston with participants from each step in the supply chain, including first receiver Atlantic Coast Seafood, processor/wholesaler Ipswich Shellfish Group and supermarket chain Wegmans. The system also has support from the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries’ Seafood Marketing Program. Focusing on New England haddock, redfish and pollock, the program will enable product differentiation and help reduce the amount of imported groundfish sold erroneously as “local,” in turn increasing ex-vessel values — price paid for the catch upon unloading — for fishermen.

Over time, end-to-end traceability should also help reveal how well quotas and other regulations are working. Before you know it, that photo you post on Instagram of your haddock sandwich will tell a story not only about what’s on your plate but also about the entire supply chain. Solutions like these are one way of ensuring that sustainably harvested fish, and the industry players who source them, are at the table.

Author

Laurie Zapalac is the founder of Zapalac Advisors, a Boston-based urban planning firm providing research and strategic planning for urban revitalization and enhancement. Laurie is passionate about understanding how and why digital technology is making historic urban environments newly attractive as places to live, work and play. When not traveling farther afield, you can find her trekking the New England coastline and enjoying local bakeries.