Remember when you had to leave your house to eat restaurant fare? Today, eateries and delivery companies are working together to bring the restaurant dine-in experience straight to your dining room. Eating out in is just a click away. Here’s how it works.

“I ‘favor’ all the time.” Like many Austinites, Pete has co-opted the name of the local food delivery service Favor as a verb.

Exhausted after a multi-city business trip, he sinks into his gray green leather couch and plants stockinged feet onto an oversized ottoman. Plucking his smartphone from a row of remotes, he opens an app and scrolls past bright photos of tacos, pancakes and pho. He settles on an upscale neighborhood Italian restaurant and, within seconds, has sent an order into the ether. Almost immediately he receives notification that a runner named Joshua has grabbed his order.

Pete grins. “I cook at home when I have someone to cook with and for, but tonight it would cost me just as much to go to the store to buy food for a meal. And I’m lazy.” Pete’s not alone.

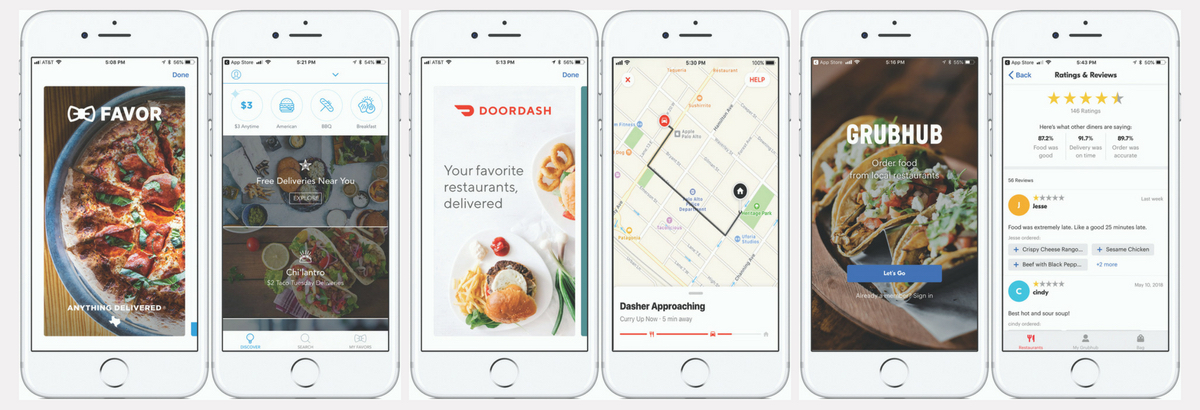

Favor, along with other meal delivery services like DoorDash, Uber Eats and GrubHub, is part of a rapidly growing niche within the foodservice industry. And they’ve become a boon to an otherwise mildly stagnant sector of the economy — restaurants. A recent study by industry analyst Bonnie Riggs, of market research company NPD Group, finds that half of meals purchased at restaurants are now eaten at home. She predicts that the future trajectory of the industry could improve if restaurants focus on providing consumers with the choices and fast delivery times they need and want.

In short, people from young professionals to busy families are increasingly taxed for time and stressed. One solution is to recover time typically devoted to shopping and cooking by browsing delivery menus. Five years ago, home delivery was largely still the realm of the pizzeria. In fact, Favor’s origin is intertwined with pizza through the college job experience of the company’s founders.

“Ben Doherty and Zac Maurais admit that they were probably the geekiest pizza delivery guys,” says Keith Duncan, senior vice president at Favor. “They were constantly calculating on spreadsheets the most efficient delivery routes.”

Favor, like many of its competitors, started about five years ago. Austin was its first market; now the company is concentrating on expanding into additional Texas cities. Duncan estimates that, since launching in 2013, Favor has completed more than seven million food deliveries — and 90 percent of these were prepared meals from restaurants.

“On the front end, we have a consumer app for placing an order, and on the back end there is a system that makes sense of all the orders and assigns them to delivery folks — runners — who can communicate with the customer once they accept the order,” says Duncan. “We are constantly optimizing the experience to increase the speed of delivery, and we encourage customers to order within a certain radius of their home because proximity is really important for the quality of what is essentially takeout.”

How has this new business model developed so quickly? A confluence of several factors — including the normalizing of cashless, online retail over the past decade, the fact that three people out of four Americans now own smartphones and a trend that sees half of all Americans using their phones for online purchases — has led to a rapid increase in mobile commerce. In fact, it is predicted that by 2020, m-commerce will catapult to include nearly half of total U.S. digital commerce, reaching $284 billion.

Even more critical to today’s digital meal delivery system is a new workforce made up of independent contractors. Favor, for example, uses more than 25,000 runners who snatch orders when they want to and deliver meals in cities using their own cars, scooters or bicycles. The benefit of this flexible workforce to restaurants — and pizza parlors! — is huge, since the delivery team is made up of on-demand contractors rather than regular employees, who would need to be paid by the hour regardless of whether they were out making deliveries.

More traditional restaurants also benefit by taking advantage of what is, essentially, a new revenue stream. According to a 2015 study by the delivery company GrubHub, restaurants that add digital ordering average a 30 percent increase in revenue from takeout. Anecdotally, Favor’s Duncan knows of hundreds of restaurants that avoided closing by capitalizing on this new revenue stream. Digital meal delivery is so successful that there is now a new trend in some cities: “ghost restaurants,” which are essentially just kitchens, with no table service or wait staff.

The growth of the meal delivery industry is also a boon to the companies who develop the digital apps. All seem to be capitalizing on the service provided by the flexible workforce. Favor delivers more than meals — everything from milk to medicine — which will only expand now that the company was recently acquired by regional supermarket chain H-E-B. DoorDash is no exception. Headquartered in the Bay Area, this company has expanded into numerous cities across the country to efficiently deliver any purchase.

“The vision for DoorDash is not just [being] a food delivery company but instead a logistics platform, [striving] to become experts in delivering anything in a city from point A to Point B,” says regional general manager Benjamin Lipson. “We get increasingly sophisticated and learn from our experience, incorporating it in our algorithms and focusing on optimizing travel time.”

Twenty-seven minutes after placing his order, Pete’s doorbell rings. There is Joshua, plastic carrier bag in hand. The exchange is seamless and short because Pete has already paid for his meal, delivery fee and tip through the app.

He now has the ultimate TV dinner for his night at home: delicate rounds of roasted beets and oranges resting amid bright specks of fennel and mint, followed by a perfect portion of beef nestled in polenta, shallots and savory gremolata.

Can you smell the sweet, layered herbs in the vinaigrette? Yum!

Author

Kristin Phillips never knew that — after half a decade observing how rhesus and woolly monkeys compete and forage for food — she would write about how Austinites procure dinner by tapping their smartphones to order a piping-hot meal from a favorite local restaurant. Previously the science publicist at The American Museum of Natural History and with degrees in journalism and biological anthropology, Kristin currently writes for the Office of Sustainability at The University of Texas at Austin.