Since the Civil War, beef has been central to Texas’ agricultural economy. The movement of all those cattle, from ranch to slaughterhouse, shaped the state’s modern highway system — literally.

Fourteen-year-old Frank King, a cattle drover in the late 19th century, was responsible for moving cattle through Texas and points north. Back then, men and boys on horseback rode through the fields, plains and hills of what’s now the center of the country, forming trails that remained long after the last of the cattle drives — trails that became some of this country’s most well-traveled highways.

Conceptions of Texas, for natives and non-Texans alike, often begin with sepia-tinged images of cattle drives, visions of sprawling ranches and the smoky smell of slow-cooked beef briskets. Since the Civil War, beef has steadfastly remained at the center of Texas culture and its agricultural economy. But while beef is no longer the state’s largest export product, the paths taken by beef cattle to go from range to market had a lasting impact on paths developed for human travel. The legacies of moving cattle to market on the hoof still shape how people, animals and products move into and around Texas.

“I was only fourteen, but had been learnin’ the work on the Bill Chisholm Ranch on the Canadian River in the Chickasaw Nation,” recalled a much-older Frank King in an oral history recorded in the 1930s and housed at the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History. As he recounted the mechanization of his “Old West” way of life, he noted the stark changes he’d seen in the previous 60 years. “The young fellers can’t vision the broad Plains, now covered with wheat fields” — in the 1930s when he recorded these memories — “…as once bein’ the home of millions of buffalo grazin’ and runnin’ across ’em, lookin’ like great big black waves as they moved from North to South, changin’ with the seasons.”

Managing a herd of hundreds or even thousands of animals required a kind of choreography. A team of drovers, as cowboys were more accurately known, spread out around the herd, keeping strays from wandering too far off course. They were on the hoof together for weeks at a time, covering distances of hundreds of miles between ranch and beef processor. Image from “Cattle Drive,” from Flint Hills Cowboys, Jim Hoy. Click on the image to enlarge.

Erwin E. Smith (1886-1947); A coyote trapped at the carcass of a range critter. Three Circles Ranch, Texas.; 1906; nitrate negative; Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, TX; LC.S59.215

Erwin E. Smith (1886-1947); The loading yards at the railroad station; one of the first shipping points to be established on the Texas plains. Lubbock, Texas.; 1910; Nitrate negative; Erwin E. Smith Collection of the Library of Congress on Deposit at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas; LC.S59.585

Today, those waves moving along the north-south corridors of Texas are made of motor vehicles. Interstate 35 is the main road that runs north and south through Texas, forming a highway spine from Mexico through the American heartland all the way north to Lake Superior. Yet the very things that make it modern — its expanses of pavement and high speeds — also obscure the unique history of this strip of ground in Texas. When we drive up I-35 in Texas today, we are following a movement pattern carved out by bovine hooves — first by wild bison, as King remembered, and then by ranched cattle. That’s hard to imagine now, as the concrete hums under the tires and the landscape whizzes by in a blur.

Unbeknownst to most motorists today, including truckers moving cattle through various points of the beef commodity chain, Interstate 35 overlays the same path taken by cattle drovers, the first men on horseback to guide Texas cattle to northern markets in the 19th century. Men like Frank King. “When I started to ridin’ them North Texas ranges, barbed wire hadn’t been invented,” he remembered. “There was nothin’ to hold cows together but cowboys and hosses.”

Topography helped, too. King and his fellow drovers followed existing wild bison trails that hugged the geological guide of the Balcones Escarpment. The drovers were hired to walk Texas cattle to railroad depots in Missouri and Kansas, but in the early days there was no set route. The cattle themselves found and followed these tamped-down bison trails. “It was a wonderful sight to see herds of them lanky old cattle strung out along the trail. Folks didn’t drive cattle in them days,” he noted. “They moved ’em, lettin’ ’em graze along in the right direction ’til they reached the northern markets or grazin’ grounds.” Even for someone who was there, the past seemed very far away.

Chisholm Trail

Chisholm Trail

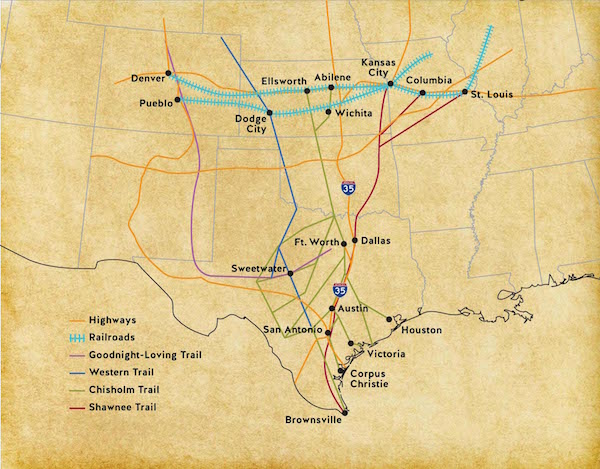

The trail known as the Chisholm Trail guided Texas cattle northward through Indian Territory, no matter where the cattle came from in Texas. It was first marked out by a Cherokee man named Jesse Chisholm to provide safe passage for cattle moving north from the Red River to Abilene. Later, the Chisholm Trail came to also include a route from San Antonio to the Red River, and today the route is mostly overlaid by Texas Highway 81.

FROM TRAILS TO RAILS TO ROADS

In contrast to the well-established east-west corridor known as the Old San Antonio Road — the Spanish Texas version of El Camino Real — north/south routes in Texas were inhospitable to Anglo settler colonists in the 1820s moving into what is now Texas. The east-west routes of the Old San Antonio Road were a series of trails blazed in the late 17th century to ferry people, animals and commodities from Louisiana deep into the Spanish Empire. But the route north from San Antonio remained remarkably unchanged, even in the days of the Texas Republic and Texas’ entry into the United States in 1845, and was used almost exclusively by bison and indigenous nations. More passable long-distance routes beyond El Camino Real didn’t emerge until after the Civil War.

This timing had much to do with the post–Civil War militarization of the western plains against indigenous people, which opened up territories to settler colonists. At this point, any new route across Texas was designed to funnel resources toward burgeoning markets. Yet even in this moment of rapid modernization, the most enduring route from southern to northern Texas was formed by bovine hooves with a twist: they were beeves, not bison.

From the 1840s to the 1890s, cattle moved northward from Mexico and Texas on the hoof, grazing on lush grassland prairies during autumn before boarding a train in winter to feed the meat demands of industrial cities to the east. The Shawnee Trail, an indigenous and bison-maintained trailway that prefigured I-35, was the first popular route to bring Texas cattle to northern markets in the 1840s and 1850s because it connected with rail and port systems in Missouri.

King rode the trails during the rise of ranching in the 1870s. As Anglo settlers took over more and more indigenous land, “there was no fences at first and cattle herds was located on ranges and kept there by line riders and sign riders,” effectively grazing within the living fences made by King and his fellow hired hands.

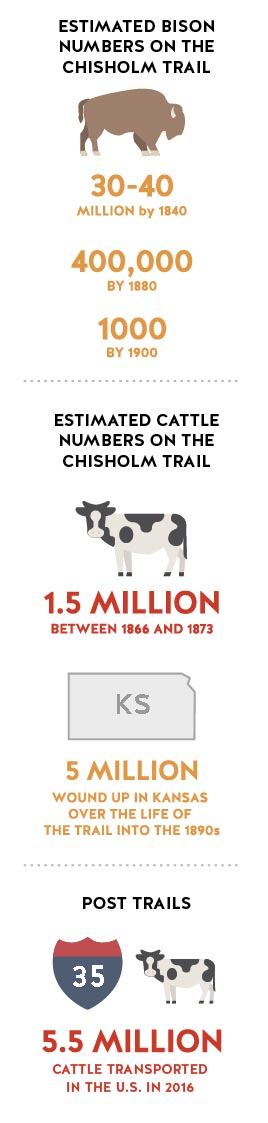

The financial stakes were high for this fast-growing industry. After the Civil War, Texas cattle numbered in the millions, and postwar cattle capitalists eagerly resumed the pre-war Shawnee Trail route in 1866. As railroads crept further west, cattle entrepreneur Joseph McCoy opened a depot in Abilene, Kansas. This reorientation to a more western terminus inaugurated the famed Chisholm Trail, guiding Texas cattle north straight through Oklahoma Indian Territory into Kansas. The Texas State Historical Association estimates that more than 1.5 million cattle tamped down the Chisholm Trail between 1866 and 1873; other sources estimate that more than 5 million cattle wound up in Kansas over the life of the trail into the 1890s. The powerful trail-making capabilities of thousands upon thousands of bovine hooves made parts of Texas navigable by settlers for the first time.

When cattle arrived in Kansas, they rested and grazed on the tallgrass prairie before loading up on trains. The locations of the northern railheads were ideally situated near grasslands to fatten cattle before their final journey to slaughter — a circumstance that kept cattle traveling out of Texas by hoof even after railways had been well established in the state. Indeed, Texas rails were plentiful in the era of on-the-hoof mobility. Rail access across eastern Texas flourished between 1870 and 1880, when the number of rail miles more than quadrupled, from 700 to 3,293. Much of this was passenger rail that connected towns to cities.

Connecting goods to markets was harder. In the 1870s, the explosion of Texas railways did not immediately affect cattle drives, in part because freight fees were far higher than drovers’ costs and most railroads were built in the eastern part of the state. This left the Chisholm Trail mostly free of rail crossings. The early Texas rail system was simply not designed to move beef north, but rather to move profitable cotton crops east and move people from town to town. Rails revolutionized human mobility across Texas, enabling many Texans to break free from their small towns when roads were few and far between. But as rails expanded east and west, cattle still cut the most important northward routes.

Texas Traffic: Cattle to Cars

The routes cattle drovers took laid the foundation for many of Texas’ modern highways. The ground, tamped down by decades of cattle drives — and millennia of migrating bison — gave way to roads in the middle of the 20th century. Interstate 35, the main north-south artery that bisects the state, follows the old Shawnee Trail. Click on the image to enlarge.

CATTLE TRAILS BY THE NUMBERS

The Texas State Historical Association estimates that more than 1.5 million cattle tamped down the Chisholm Trail between 1866 and 1873; other sources estimate that more than 5 million cattle wound up in Kansas over the life of the trail into the 1890s.

RAILS AND FENCES

In the 1880s, barbed wire began to replace men on horseback as the preferred method for keeping ranch cattle contained, and rails expanded westward into the state. By 1890, rails and fences blocked the Chisholm Trail, helping to bring the cattle drive era to an end. In 1900, the movement of cattle across Texas was no longer a long grazing walk, but rather a journey of multiple short segments. For example, North Texas cattle raisers would drive their cattle a short distance to Fort Worth on the hoof. Then, a major meatpacker like Swift and Co. would buy cattle from the Fort Worth stockyards and put them on a train to one of the 20 feed yards they ran in Texas. The last stop on the trail was the slaughterhouse, where the meat was packed and shipped by refrigerated rail car to markets across the nation.

Cattlemen no longer had to bear financial responsibility for their animals during the long walk northward. For men like King, this spelled the end of a way of life. “The younger generation will never have the thrills and experiences of the old-time fellers before, during, and immediately after the wire fence days, when a cowhand didn’t have anything to do but ride them side-wheel ponies after cows.” Cowhands still guided cattle a short distance to local rail yards, but for half a century — from about 1900 to after World War II — the grand and ancient bovine trails through Texas were barely used at all.

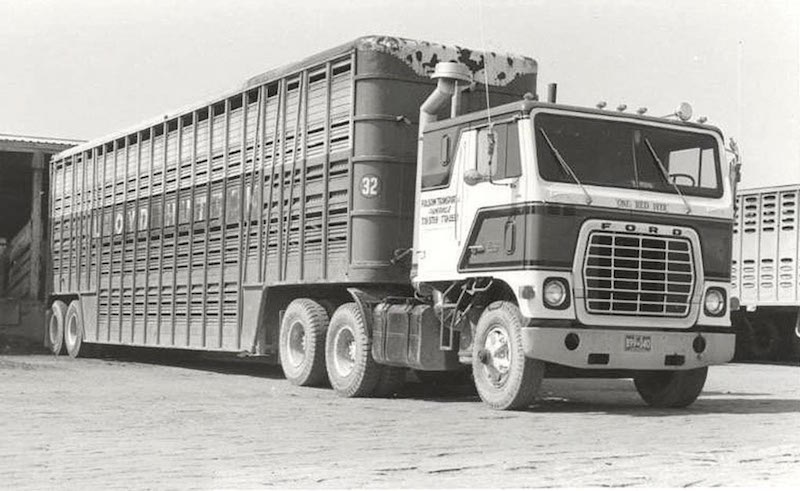

The Shawnee Trail was reborn as Interstate 35 through Texas in the early 1960s. It joined a 24,000-mile network of rural roads in Texas that was paved between 1945 and 1955. Turning the Shawnee trail into Interstate 35 opened this route back up to cattle, but it also heralded the end of cattle walking across Texas. By 1965, flatbed semitrailers brought cattle north from their home ranches — whether to be fed in a Panhandle lot, to graze on the Tallgrass Hills of Kansas or to be distributed as meat products to grocers and food producers around the country.

Roads like Interstate 35 reproduced some of the oldest navigable routes that bovine critters had used to cross Texas for centuries — routes that had been generally unavailable to them since the end of the 19th century, but to which they returned on wheels, no longer on the hoof. This pattern of movement from ranch to lot, facilitated by the rural and interstate highway system, still describes how beef cattle move around and out of Texas.

Trail Boss

Margaret Heffernan Borland ran a large cattle operation from Victoria, Texas, with her husband, Alexander, in the 1860s. She took over the business when he died of yellow fever in 1867. Within a few years she grew her herd to a whopping 10,000 head and regularly sent herds of 2,500 or more up to Kansas railheads. She procured and organized the supplies and hired the laborers for these drives. In 1873, she led a drive from Victoria to Wichita herself. Like many at that time, she caught an illness along the trail. She died shortly after arriving in Kansas.

TRAIL LEGACIES

Frank King witnessed a wholesale transformation of the way cattle were raised and sold. These changes were hard to miss because they were geographical as much as they were logistical: Indian territories shrank and disappeared, fence posts appeared on landscapes and rail beds rose up across well-tamped trails. King did not live to see the day cattle were loaded up on highway haulers, but he did observe one way in which rural roads affected the lives of cattle workers in 20th-century Texas. While cattle droving was “sometimes scary when the Comanches were on the prod,” it was not “half as dangerous as it is nowadays tryin’ to cross a street or highway on foot when a band of modern Apaches is passin’ along armed with one of them high-powered automobiles. Personally,” he added, “I’ll take my chances with the Comanches.” Perhaps he had an inkling that paved roads would spell the end of his kind of work for good.

Change in the cattle industry is harder to see now. While the geography of modern cattle logistics has remained steady, changes affecting the beef industry have occurred in the less-visible areas of veterinary medicine and nutrition, market regulation and animal reproduction.

King, who experienced an era of incredible change from the back of a horse, could not foresee the days of the 75-mile-per-hour cattle trail, just as the Shawnee, Apache and Comanche residents of Texas could not have foreseen the transformation of their bison trails into commercial cattle routes. But for the last 500 years, the route they followed has remained the same.

Author

Jeannette Vaught is an American Studies Ph.D. who splits her time between Austin, Texas, and Long Beach, Calif. Her veterinary background and interest in technology and culture inform her writing about animals, agriculture, food and science. She produces the podcast “The Range” for Foodways Texas, and is working on Locust for Reaktion Books’ Animal Series, when not lavishing carrots upon her aged horse.