Have you ever had a compost bin full of bits and druthers that you think are almost edible? You know, the thin peels of broccoli or carrots or apples? What about a refrigerator drawer with wilted greens or the selection of cheeses you got for that cocktail party a month ago? Do you just chuck them out, concerned that they’re not fresh enough to use or be delicious?

And what about the money you spent on those ingredients? Or the costs of producing them? Does tossing no-longer-fresh food take a toll on your grocery budget, as well as your environmental conscience?

As landfills are increasingly brimming with food that was produced but never consumed (for a variety of reasons), it may be time to reconsider the ways in which we assign a value to ingredients. After all, in less affluent eras — or areas of the world and the U.S. — people couldn’t afford to waste food products that could still contribute to a tasty and nutritious meal. Think of it as a really good time to figure out how to be creative with your organic kitchen matter.

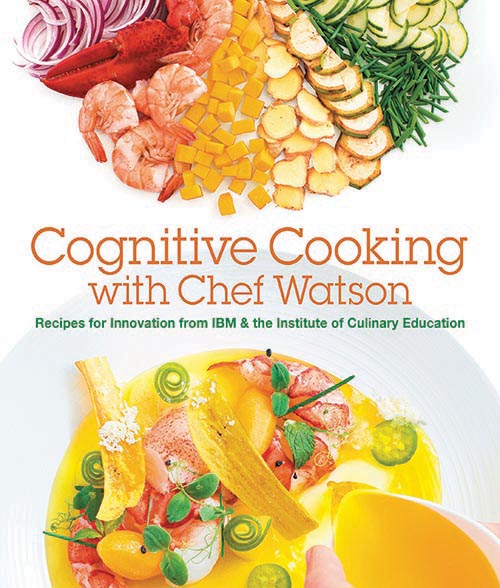

The good news is lots of people, including some of the world’s best chefs, are working on ways to address this very issue. In fact, two recent cookbooks — or, let’s say, sources of recipes — approach the notion of creating a dish from opposite ends of the spectrum. One, “Bread is Gold,” by the world-renowned chef Massimo Bottura, is a collection of recipes and stories by and about a variety of chefs who were called to cook using only products that arrived at a pop-up soup kitchen during the 2015 Milan World Expo as excess, day-old or deemed insufficiently fresh to sell.

The Expo’s theme, “Feeding the Planet, Energy for Life,” spoke directly to Bottura, who worked with a parish priest in the city to transform an old theater into a dining hall that could accommodate, restaurant-style, 100 guests each day — serving lunch to area school children and supper to local homeless people.

For the fancy chefs who came to Milan to cook for a day or two at the Refettorio, their constrained ingredient lists were the catalysts to their creativity. Deliveries included days-old bread, produce in various states of maturity or discoloration, cheeses and other dairy products that were nearing or past their sell-by dates. Each day’s supplies were different and unpredictable. After the initial shock of the arbitrariness of that day’s delivery wore off, the enterprising chefs got straight to work, creating delicious and comforting meals for their guests.

“Something of apparently no use could become a secret weapon in the kitchen, a super power that could magically transform a dull dish into a vibrant one,” Bottura writes about the solution Chef Cristina Bowerman devised for using the outer — and often discarded — leaves of vegetables: Dry them and grind them into intense powders that add stealthy flavor to dishes. (She’s not the only one who makes savory powders from dehydrated vegetable peels; read on.)

The chefs wasted nothing because very little was available to start with. Even banana peels were used to make a chutney. It was a revelation, even to one of the world’s top chefs, Bottura. “If you open your mind and start thinking differently about ingredients, then you no longer have to throw away a banana peel ever again,” he writes.

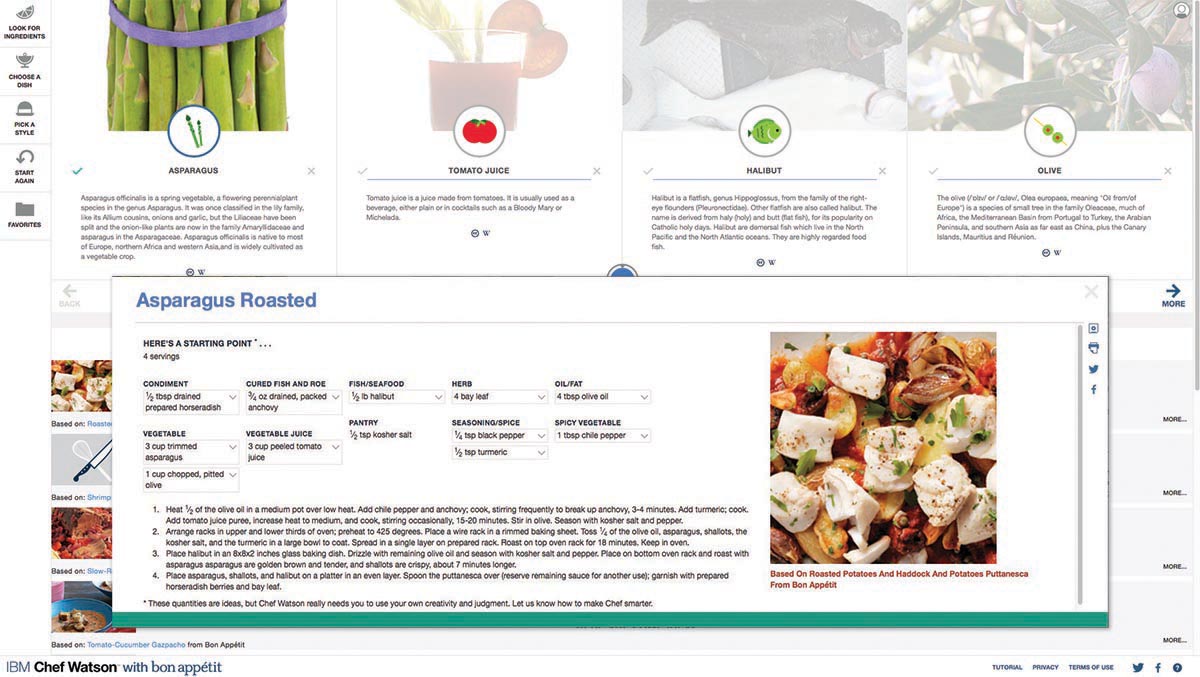

By contrast, for Chef Watson, developed by IBM — yes, that Watson — the sky’s the limit when it comes to ingredients. Through machine learning and algorithms, an online app called Chef Watson will take in up to four ingredients that you suggest (whether or not you see how they might result in something delicious) and output a set of instructions that it “believes” will create an edible dish. Chef Watson offers a never-ending source of combinations for any ingredient under the sun. [Editor’s note: Alas, IBM closed its Chef Watson site in June 2018.]

The computer ingested the entire archive of Bon Appetit magazine, as well as a huge dataset of different ingredients and their detailed flavor profiles. From there, Chef Watson learned to recognize synergies — ingredients that seem to go well together (understood perhaps by frequency of pairing or through the logic of their marrying profiles). Garlic and tomatoes. Mushrooms and butter. Pork and apples.

As the recipe appears on screen it displays three graphic measurements — synergy, pleasantness and surprise — that help the user determine how the hypothetical dish might turn out. Just as constraints fueled the chefs at the Milan Refettorio, the search for novelty drives Watson’s recipes.

While the platform is available online for anyone to use, Chef Watson has been on a few roadshows, employed by featured chefs to make novel dishes. The chronicle of these events is a book called “Cognitive Cooking,” another collection of experiential narratives and try-it-yourself recipes.

“Cognitive Cooking” shares stories and recipes by IBM’s Chef Watson, which generates recipes from any combination of ingredients. The key to success? Human chefs who applied their knowledge and experience to effect a delicious outcome.

Central to the recipe successes shared in the book are the chefs — the human cooks — whose expertise and creativity helped shape Watson’s “suggestions” of unusual ingredient combinations into viable outcomes. For instance, an early trial was a pastry recipe for Spanish Almond Crescent. But the ingredient list included more liquids than would work to make a stable dough. A chef at the Institute of Culinary Education tweaked the recipe, substituting some ingredients for others to ensure a satisfying outcome but still maintain the flavor profile Chef Watson suggested.

“This is the nature of the human-machine collaboration,” the book notes. “The computer doesn’t dictate. It suggests.”

For IBM Watson Group Engineer Florian Pinel, Chef Watson has great potential to help people eat more healthfully by personalizing recipes according to dietary constraint and personal preference. It also could help reduce food waste by making suggestions based on what lurks in your refrigerator, finding ways to use the last of those beets along with the remains of the star fruit and ground pork you bought for last weekend’s cooking project.

“People can create new, personalized recipes on the fly,” Pinel said in a 2014 TED@IBM talk. “People can cook food that’s flavorful and healthy without ever eating the same thing twice.”

Whether you come to your starting line with leftovers and remainders or a motley collection of ingredients for your next unique Watson creation, a key component is a human willingness to see the value in every piece of the puzzle. Whether it goes into tonight’s dinner or becomes part of the stock for tomorrow’s sauce, just about every edible thing on Earth has a value that should prevent it from simply being next week’s landfill fodder.

IBM engineer Florian Pinel talks about the thinking behind Chef Watson in this 2014 TED@IBM Talk.

That’s certainly the philosophy that drives Chef Ian Thurwachter of Intero, an Italian-themed fine-dining restaurant in Austin.

Fine-dining restaurants are often known for their pristine ingredients and precise techniques, the combination of which should result in a mind-blowing dining experience that’s hard to replicate at home. But often, there’s a cost to this level of quality, and it’s not only found in the prices on the menu.

For example, to create carrot brunoise, the delicate ⅛-inch dice that often garnish soups or stews, one must start with an irregular, round vegetable and make it square. In the same vein, to get to the heart of a broccoli stem, arguably the sweetest, most tender and delicious part of the green brassica, the outer peel must be removed first.

In both instances, once you’ve finished cutting and have the finished ingredients, ready to sprinkle or roast or puree, you also have a pile of peel and other trimmings — byproducts that often end up in a compost bin, or worse, the garbage.

Not so at Intero, where Chef Thurwachter operates a no-waste kitchen in which every stem, peel, animal organ, off-cut of meat or other commonly tossed odd and end is put to flavorful use.

This Intero dish features a pesto made from radish tops, carrot tops and almonds. Extra carrot greens top the dish as a leafy garnish.

Yum Yum powder (dehydrated fermented broccoli scraps) sprinkled over a dish that highlights the rest of the broccoli plant, grilled florets and thin slices of pickled broccoli stem.

A branzino fish entree dusted with lemon powder.

Take the humble, fibrous broccoli peel. At Intero, they pack it with salt and sugar and leave it to ferment for several days. “It balloons up, is intensely pungent, with a very off-putting smell. But the flavor is really awesome — it’s got this tart saltiness,” Thurwachter explains. “We take all that and dehydrate it and turn it into a powder that’s got this background funkiness. It’s intensely savory, and we use it as a seasoning.” (Another clever dehydrated use for vegetable peels….)

The idea for this transformation came from a sous chef who had seen some something similar with mushrooms. Thurwachter engages his team in regular brainstorming sessions to figure out how best to use all the scraps.

“About once a week it’s a necessity,” he says, “but we try to make it an ongoing thing. Every day we have projects.” Projects such as dehydrating the smoked carrots his bartender used for a cocktail. The resulting powder will go into a pasta dough. Or using remnants from artichokes that were served as a bar snack in a stock that pairs with a rabbit tortelloni. “It’s just constantly trying to move these puzzle pieces around,” he says about the challenge of using all the parts.

It’s a challenge that resembles the no-waste reality of Italian farmers of earlier generations. “I love Italian cooking more than I love Italian food because it’s really a cuisine that historically is based on poverty,” Thurwachter says. He explains how veal farmers used to sell their prime cuts to fancy restaurants in Milan and keep the off-cuts — the lower-valued and harder-to-sell cuts — such as the shanks and head, for themselves.

But just as Bottura’s chefs made scrumptious meals from undervalued ingredients in Milan in 2015, Italian farmers of yore tapped into their own creative wells.

“They came up with things like osso bucco milanese (using the veal shank), which is the quintessential Italian dish,” Thurwachter explains. And it didn’t stop there. Arancini, fried rice balls, are made from leftover rice, stuffed with leftover veal and fried the next day for yet another meal originating from humble ingredients. “And then there are these really elaborate preparations where the farmer’s wife took the time to completely bone out the veal head and roll it up into this beautiful roulade and braise it and then slice it super thin and serve it with bitter greens and a salad. I would take that veal roulade with a salad over a veal chop any day of the week,” Thurwachter says, vividly illustrating an alternative way to value ingredients.

While he’s set a different challenge for himself than Massimo Bottura or Florian Pinel, Chef Thurwachter relies on a similar asset: “Our biggest resource in the kitchen is our collective creativity.”

Author

Cory Leahy — editor, writer, runner, enthusiastic cook and veggie-leaning omnivore — has spent more than 20 years as an editor of books, magazines and websites. She recently stepped out of familiar labels and into unknown territory to reimagine a next chapter that’s all about food.