Not going to eat those carrots? Don’t throw them away. Once food reaches a landfill, its potential is lost. But unwanted food, captured before it’s tossed, can transform into energy, building materials — or even desirable food. Meet the new generation of hunters and gatherers.

Jake Milliner and Belinda Bonnen tend a towering vine of fresh malabar spinach at Joe’s Organics in Austin, Texas. Joe’s collects food waste from area restaurants and, with their composting partners, creates rich soil for their crops of baby greens.

Wherever there is food, there is food waste. Like water leaking from an aqueduct, food waste will find the gaps in the supply chain between field and plate, a journey filled with opportunities for loss.

A heartbreaking amount of produce rots in the field, unharvested. Some is culled for size, shape or another cosmetic factor. Even more food is thrown away or lost during cleaning, boxing, processing and distribution. It rots slowly in retail stores or commercial kitchens and in your fridge. Food is also tossed during meal preparation, at home or in restaurants or other commercial or institutional kitchens.

And then, far too often, the meal itself — or much of it — is thrown away. In the end, a third of the food we produce goes uneaten. Data from a new report issued by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) indicate that Americans throw out more 400 pounds of food per person per year. Sadly, in the shadow of this massive overproduction and loss of food, 10 percent of humanity still doesn’t have enough to eat.

But it’s not just about feeding the world: The environmental consequences are significant. The amount of cropland needed to produce the food that ends up as waste is roughly equivalent to the acreage of China and requires a fourth of the country’s irrigation water. Feeding people is the largest single contributor of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere of any human pursuit, and roughly 10 percent of greenhouse gases that humans release are in service of food that will not be eaten. When this wasted food rots in a landfill or is burned in an incinerator, the process releases even more greenhouse gases.

The holes in the food supply chain through which food slips away represent more than hunger and pollution. It’s wasted investment and fruitless effort that could have been channeled into something more useful. Entire cities could be built, or rebuilt, with the effort that goes into the food we throw away.

But there’s another side of the coin. The scale of this waste, and the problems it causes, have created opportunities. Wasted food is essentially money that’s being left on the table, available to whomever is crafty enough to grab it and put it to use. It has potential value as energy, soil fertility and calories — all of which can add up to dollars that can be earned from harvesting food from the waste stream, or intercepting food before it gets tossed.

Executive producer Anthony Bourdain takes a deep dive into this issue in “Wasted! The Story of Food Waste.”

Above, from top: uneaten restaurant meals contribute to the enormous amount of edible food discarded daily; byproducts from food preparation, such as this watermelon rind, can be composted or even pickled rather than chucked; food waste is a cause of greenhouse gases.

THE NEW HUNTERS AND GATHERERS

The highest good to which a piece of wasted food could aspire (if wasted food had aspirations) is to be rerouted to a hungry human mouth before being discarded. The next-best thing would be for it to be eaten by something else, like a chicken or a pig, or — in the case of food that can’t be routed to organisms with recognizable mouths — a bacteria. Today, most food waste diverted from landfills or incineration is digested by anaerobic bacteria to produce natural gas and fertilizer. Food scraps left over from food processing and retail food preparation are suited for this, as is the majority of household waste. The challenge is getting food out of the waste stream and sending it to a better place than the dump.

That best-case scenario, in which food is rescued from the edge of waste and routed to other human mouths, has been deeply explored in Europe in recent years, while the United States is playing catch-up. The players, increasingly, are for-profit waste hunters that are bringing high-tech solutions to the task of reducing food waste.

Sometimes that initiative comes from the (would-be) food wasters themselves. Campbell Soup Company has been an early corporate leader in reducing its share.

“Food that meets our rigorous safety standards is donated to local food banks in and around our manufacturing plants and distribution networks,” says Thomas Hushen, a Campbell spokesman. “In most cases, we partner with Feeding America and their network of food banks to make donations.”

While some corporations have been early and eager to embrace measures to curb food waste, other companies want to jump on the bandwagon but don’t know where to start.

Left: Malabar spinach stalk — the stalk and ugly leaves often get wasted, but they’re perfect for green juices. Right: Sorting sweet potatoes at Johnson’s Backyard Garden.

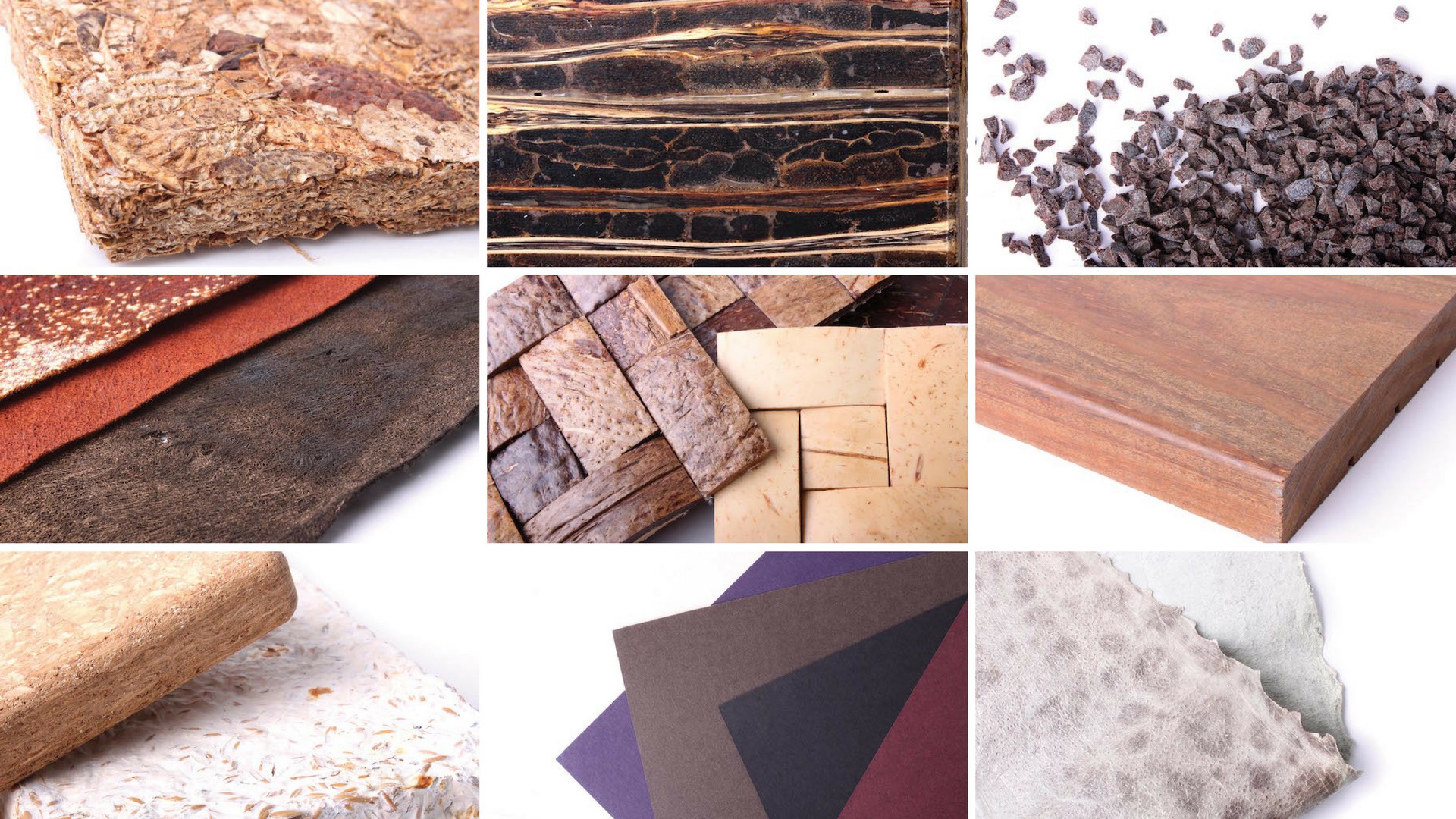

To see what kinds of value-add products are being made from uneaten food — from floor tiles made from coconut shells to plastic-like pellets made from blood meal, a byproduct of the meat industry — check out our gallery.

The French corporation Phenix (a 2017 Food+City Challenge Prize finalist) offers support services to businesses interested in diverting their food waste away from landfills and incinerators. The company has a solid track record in Europe, where the culture of food-waste recovery is more evolved than in the U.S.

But Sarah Lenoble, who heads Phenix’s push to set up shop in the States, is that rare French person who looks at America and sees a land of opportunity. The biggest reason food-waste recovery isn’t as advanced in the U.S., she says, is that the food-waste hunters are just getting started. “Even though it is happening, it’s not happening in a very structured way,” Lenoble says. To a veteran organization like Phenix, this youthful discombobulation amounts to low-hanging fruit.

Phenix uses a market-based approach that capitalizes on the fact that unused food has value even if it isn’t sold. American supermarkets, for example, must pay a waste disposal company to get rid of expired food, a fee they could forego if the food were collected by a charity. Last year, according to the NRDC, companies spent $1.3 billion disposing of food scraps, thanks largely to transport and disposal fees. Meanwhile, a surprisingly robust tax credit is available to companies that donate food: the Federal Enhanced Tax Deduction for Food Donation. It allows retailers to recover the higher retail price of their donations, even though they paid the lower wholesale price. Another law, passed in early 2017 with bipartisan support, amends the Good Samaritan Act to offer stronger liability protections to those who donate food. With laws like these in place, and companies eager to exploit them, Lenoble is optimistic about Phenix’s planned rollout into the U.S. food recovery space.

She notes that the U.S. charity scene is much stronger than in Europe, in part because in European governments often handle issues that in the States are left to charities. Even though it’s out to make a profit, Phenix won’t be competing with the food banks, churches and ugly-produce resellers. Instead, they’ll be partnering with them, providing logistical and strategic support to help these charities become more effective in their food-recovery efforts. A rising tide will lift all boats, Lenoble believes, and she likes what she sees. “We believe the market here is going in the right direction.”

In addition to its work with charities, Campbell recently doubled down on its corporate introspection, implementing its Food Loss and Waste Reporting Standard. It’s an effort to develop a benchmark of lost and wasted food, and to identify hotspots and opportunities for reduction and diversion. Like any other hunter, a food-waste hunter needs to know where the opportunities are. “We believe measurement improves management,” Hushen says.

Sarah Lenoble

After completing her MBA, Sarah worked in finance in the private sector before switching to microfinance and finally social business. Originally from France, Sarah has also lived and worked in Argentina and Italy. She is now based in Washington D.C., where she is launching the U.S. subsidiary of PHENIX, a French waste diversion social startup.

THE PERFECT FLAVOR OF IMPERFECT PRODUCE

The U.S. is so new at food recovery that one of the movement’s veteran waste hunters isn’t yet 30 years old. Fresh out of college in 2011, Claire Cummings started as a fellow at Bon Appétit Management Company (BAMCO), which runs more than 650 eateries on college and corporate campuses. A year later she became the company’s first food-waste specialist. She went on to create Imperfectly Delicious Produce (IDP), a BAMCO program that pursues ways to recover produce that usually goes to waste (mostly from farms and distributors) and serve it in the company’s many dining rooms.

Since it launched in 2014, IDP has recovered more than 3 million pounds of produce and served it as, for example, broccoli stem soup or cauliflower fritters made from small heads. While the figure sounds impressive, she admits it’s just a drop in the bucket.

“It’s a huge chunk of food that would have been wasted and was instead utilized in our operations, through purchasing and cooking it,” Cummings says. “But that is still such a small sliver of what actually is going to waste.”

She says many problems remain, but she believes they are solvable. “We’ve gone hunting for a lot of different products on farms. I’ve visited hundreds of farms at this point, large and small. I’ve seen all different types of operations: orchards, processing facilities, fields of produce,” she says. “There is so much product that is going to waste that could be rescued through purchasing if there were better systems for tackling those missed opportunities at harvest.”

WASTE ENERGY VERSUS WASTED ENERGY

Food contains energy, which powers life, makes the world go round — and happens to be worth money. The energy resides in the bonds between the carbon, oxygen, nitrogen and hydrogen atoms that make up the food molecules. When we eat, that energy is released into our bodies, where it fuels our daily escapades. Fed to animals, the energy transfers to other forms of edible potential energy, such as meat, milk and eggs, or some form of kinetic energy, such as chasing balls or pulling a plow.

Claire Cummings

Student activist turned garbage guru, Claire Cummings is the first-ever waste programs manager for Bon Appétit Management Company, the food service pioneer that operates more than 650 cafés in 33 states for universities, corporations and museums. Claire is one of Food Tank’s 30 Women Under 30 Changing Food, she’s a recipient of Saveur’s “Activist” Good Taste Award and her work has been featured in Bloomberg News, Sunset Magazine and The New York Times.

Keep up with the latest in food repurposing and follow Claire Cummings on Twitter @WasteAce.

Keep up with the latest in food repurposing and follow Claire Cummings on Twitter @WasteAce.

But most food that isn’t eaten by humans is discarded, where, depending on the local trash disposal situation, it either gets buried or burned. Incineration releases carbon dioxide and other pollutants. And food in a landfill will break down anaerobically and release methane, which is even worse (about 18 percent of U.S. methane emissions comes from food scraps in landfills).

The best-case scenario is far from the most common, but it could be. The energy in that wasted food can be extracted as methane in an anaerobic digestor and captured. The resulting energy can be used to generate green electricity or heat houses.

Anaerobic digester operations are popping up wherever there is enough available food waste to make them feasible. Sewage treatment plants are the ideal places to build these operations because co-digesting allows the food-waste recovery process to piggyback on the existing infrastructure of the water-recovery process, rather than requiring a new facility.

Construction began in June 2017 on the Wasatch Resource Recovery Project (WRRP), Utah’s first anaerobic digester facility. A partnership between South Davis Sewer District in North Salt Lake City and the private Alpro Energy and Water, the WRRP is going up adjoining the county sewage treatment plant. Morgan Bowerman, sustainability manager for WRRP, is pleased with the arrangement.

“The South Davis Sewer District has been operating the most efficient wastewater treatment in the whole state for years,” Bowerman says. “The fact that we have these guys on board to run our digesters is huge. The other major advantage is that here in the West we are in a massive, 17-year drought. When we co-locate, we can use their wastewater, which is a huge boon to us and so much better for the environment.”

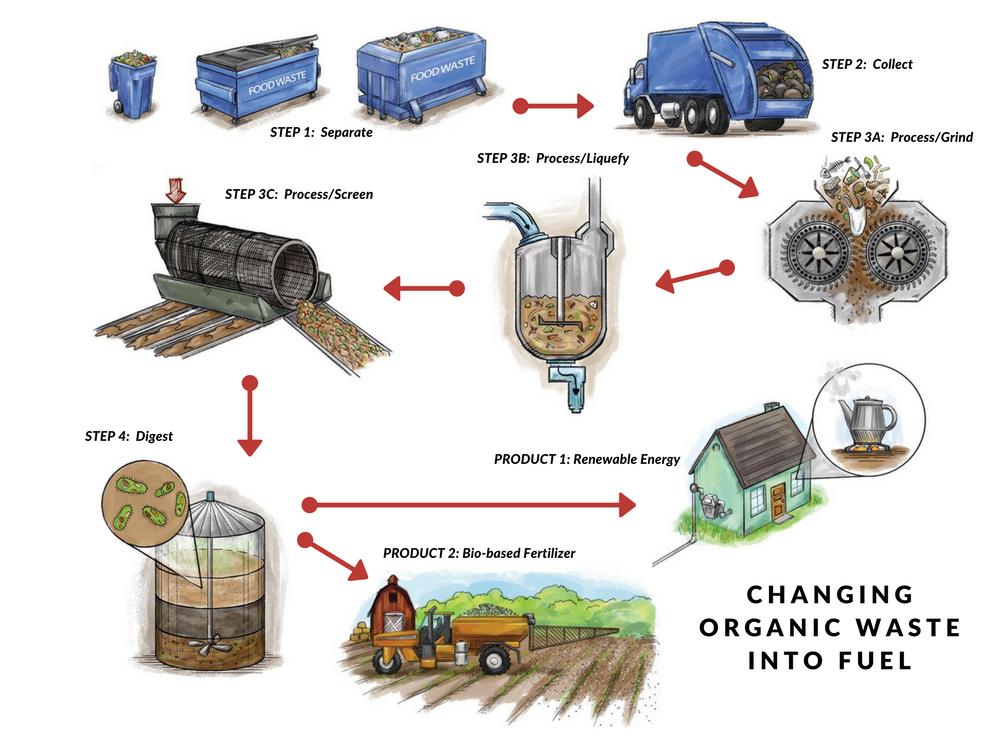

Step 1: Organic waste is separated into a designated container at a food business. Step 2: Waste is collected and delivered to Wasatch Resource Recovery facility. Step 3: Machines process the waste to remove contaminants or non-food. A. It goes into a grinder to be chopped into small pieces. B. Secondary (not potable) water is added to ground-up waste and mixed until it liquifies. C. The material passes through a screen where packaging or contaminants are washed free of remaining organic material, which is fed into the digester. Step 4: In the digester, waste is heated to aid growth of microbes, which break down organic matter without using oxygen. This produces biogas. Product 1: Biogas is captured and purified before being converted into biomethane (renewable natural gas), fed into nearby gas pipeline and sold as renewable “green” power. Product 2: The remaining product is a nutrient-rich, carbon-based fertilizer for crops.

Phase one of the project involves two 2.5-million-gallon digesters, to be operated, as mentioned, by the county sewer district. There will also be a “depackaging facility” to relieve expired edible goods of their containers. “It exponentially increases how much we can recycle. They can send it to us completely boxed and packaged, and we can do the depackaging and suddenly it’s viable,” Bowerman says.

They also have a F.O.G. (fats, oils and grease) receiving station and a depackaging station specifically for expired cans and bottles. “We can use the product inside to make energy and recycle the packaging.”

After the methane is recovered, what comes out is a nutrient-rich sludge, high in nitrogen, potassium, phosphate and organic matter — basically, fertilizer. Bowerman anticipates theirs will eventually be certified organic, once they determine its final form. Meanwhile, they’re also separating the ammonia and carbon gas from the methane for beneficial use. Wasatch plans to be operational in fall 2018.

Of the more than 1,000 sewage treatment plants in the U.S., about 216 are co-digesting food waste alongside sewage. That means 83 percent don’t yet have a food-waste digester, which amounts to a lot of money and energy being left on the table.

While pioneers like Wasatch are taking this plunge, the whole waste-to-energy industry is still coming of age. Groundbreaking advancements are frequent: Scientists at Cornell University have been playing with a process called hydrothermal liquefaction, which is a fancy way of saying “pressure-cook the food waste into oblivion.” It’s a process that recalls the way dinosaurs and their ecosystems were turned into oil under the ground. In the case of hydrothermal liquefaction, heat and pressure combine to turn food waste into an oily liquid that digests in days, rather than weeks, with more complete digestion and energy extraction.

Meanwhile, 97 percent of food waste is still getting away — for the moment anyway. But it’s only a matter of time before this low-hanging food waste will be plucked, because we can’t can afford not to.

“We wouldn’t take a barrel of oil and bury it,” Bowerman says. “And that is what we are doing with our food waste.”

COUNTERTOP COMBUSTION

The largest garbage disposal company in the world, Emerson, wants into the food-waste energy business. Any food industry player of a certain size that deals with large amounts of raw food can install Emerson’s subunit called Grind2Energy in a food disposal area. It includes a stainless steel work area, sink and a very powerful garbage disposal. Plumbing connects it to a special holding tank for the slurry, which features a sensor that notifies Grind2Energy when it’s time to be emptied. The free service saves the client in waste transport, disposal fees and kitchen labor.

Author

Ari LeVaux writes Flash in the Pan, a weekly syndicated food column that appears nationally in newspapers. His work has appeared in Outside Magazine, Slate and elsewhere. He lives with his family in Missoula, Montana.