Stories

Panama’s Big Bet on Big Ships

A century after the Panama Canal opened, Panama is opening a second set of locks this year that will welcome some of the world’s largest ships. This globe-changing expansion has U.S. farmers celebrating and port officials scrambling, but what does it mean for your plate?

In 2006, the Panama Canal had a problem.

Researchers predicted that by 2012 the canal would be maxed out. The 48-mile-long series of locks, an industrial miracle nearly forgotten by most of the people who benefit from it, would either have to turn ships away or raise prices to decrease demand. Panama’s President Martín Torrijos proposed an expansion of the canal, and in 2007 it began. That’s where our story begins, sort of.

America’s demands for growth — and for fresh food from the other hemisphere — shaped the canal as much as the canal has shaped Americans. Teddy Roosevelt’s brash international ambitions brought the canal into life, which in turn encouraged a century of accelerated consumption and a need to expand the domestic infrastructure to support it. These networks and consumption patterns underlie what foods we see in our supermarkets and how much they cost.

This year, the canal expansion will finally open, but most customers won’t notice anything different in their grocery cart. Why? Because when it’s working, infrastructure is invisible. Water, electricity and food flow in and out of our homes, but we don’t often consider how the links of the supply chain rely on each other. What happens when one of those links doubles in size?

CONNECTING THE OCEANS

Around the time gold was discovered in California, Frenchman Ferdinand de Lesseps secured permission to build a canal from the Khedive of Egypt in 1854. Construction on what became the Suez Canal began in 1859 and lasted just over 10 years. On the heels of completing the project, Lesseps began to eye Panama.

It took more than a decade, but by 1881 Lesseps had raised funds to build a sea-level canal. He underestimated the time and funds needed to complete the project, but even more daunting were the increasing deaths of his workers who fell ill and died faster than he could replace them. Still not known to transmit disease, mosquitoes were rampantly spreading yellow fever and malaria. By 1884, more than 200 men were dying every month.

Eight years after work began, all the money, more than 1.2 billion French francs, was gone. The project continued on life support until a suitable buyer was found. The asking price: $109 million U.S. dollars. But France was in a bind. They’d sunk hundreds of millions into their failed canal attempt and were still losing cash and workers as they attempted to slow the deterioration of machinery and excavation. The price tag left them with few options for buyers. The United States was an ideal prospect but had leverage — investing in a second canal route that had been found in Nicaragua. When the U.S. put in the lowball offer of $40 million, France had to take it.

The U.S. formally began its canal effort in 1904. By then, officials knew that mosquitoes were the root cause of many illnesses and had access to some preventive medicines. With a more stable workforce, the man running the project, John Frank Stevens, could solve the other major problem: how to build a canal that didn’t require removing millions of tons of dirt. Instead of a sea-level canal, he petitioned for a lock system on two sides of a man-made lake. Each lock would fill with water and empty itself to raise or lower a vessel.

Engineers built Gatun Lake, an artificial body of water 85 feet above sea level, and constructed the three locks on each side to manage the water level as ships passed through the main cut. In 1914, a thousand ships would navigate the canal locks. Nearly a century later, over 14,700 ships traversed the canal per year. Now, during the high season, it is not uncommon for vessels to wait 10 days before transiting the canal. It can cost shippers as much as $50,000 per day to sit idle, stymied by a complex bidding system for a slot in the canal.

The new locks, opening this year, are wider and run parallel to the current locks. The locks allow for ships that are 51 percent wider and 24 percent longer, which translates to 177 percent more containers per ship. Currently the project is $1 billion over budget, with estimates placing the total expansion cost at about $7 billion, about 20 percent of Panama’s. Though the canal expansion has only just been completed, Panama is considering a second expansion to build a fourth set of locks. Estimates put that project in the range of $15 to $20 billion.

The impact of this current expansion can only be imagined. About 55 percent of U.S. agricultural products are shipped through the Panama Canal. After the expansion, up to 80 percent of those products are expected to be shipped through that waterway. More grain passes through the canal than any other item or good. It’s difficult to calculate just how much the new canal will influence food prices, in part because the cost of fuel makes up half of a ship’s operating costs and bigger ships require more fuel to move. Whatever the outcome with regard to prices, it is likely that consumers will enjoy a wider variety of food ingredients as greater capacity will enable a more diverse food supply.

But the increased capacity may not be fully utilized until the global economy gets back on its feet. In 2015, shippers began seeing the impact of erratic movements in world currencies and the lagging economies of developing countries. This slowdown in global economic growth caused large shipping companies such as Maersk to cut back on plans for building new container ships. Stockpiles of empty containers sitting at ports without food to ship also signaled a dampening of hopes for full utilization of the canal expansion.

A wider channel and second set of locks that can accommodate post-Panamax ships now run parallel to the existing Panama Canal. These are the Miraflores locks, the closest to the Pacific. Image by Mike Kelley.

The Panama Canal took more than two decades to complete, including nine years to dig out the 9-mile-long Culebra Cut, which crosses Panama’s continental divide.

Skipping the Line

In 2006, a British oil tanker paid $220,000 to jump ahead of 83 other ships.

BIGGER AND BETTER

The new locks allow for ships that are 51 percent wider and 24 percent longer. This translates to 177 percent more containers per ship.

AN INTERSTATE HIGHWAY SYSTEM IS BORN

Forty years after the Panama Canal was completed, another globe-changing link in the shipping infrastructure came to life: The U.S. Interstate System.

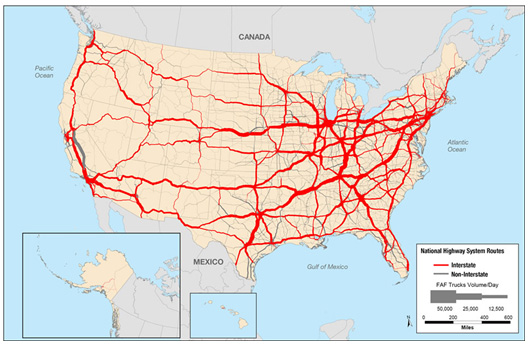

After the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration spent $4 billion (nearly $68 billion today) building and improving roads from coast to coast. With asphalt below the tires, the trucking industry started to take root, and by 1956, President Dwight D. Eisenhower authorized the interstate highway project that now encompasses 47,856 miles of road. Since the 1960s, the number of 18-wheelers has increased from fewer than than 1 million to more than 3 million, and the number of registered vehicles from 74 million to more than 255 million now.

After the highway system opened, intermodal shipping expanded quickly, but we were still missing one key piece, which would neatly link how we moved freight across both land and sea: the shipping container.

Average daily long-haul traffic on the national highway system in the U.S.

THE TWENTY-FOOT EQUIVALENT UNIT

At the same time as Eisenhower signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act, a shipping entrepreneur saw the possibilities of combining trucks with ships. Malcolm McLean, the founder of a small trucking company in North Carolina, sent the first modern cargo ship out to sea. He had converted two World War II tankers to carry removable containers. In the mid-1950s, he created the first container ship, Ideal-X, which transported trailers stacked above and below decks. Eventually, he built the Sea-Land Company and created shipping containers that were loaded on and off ships and transported to and from ports on trucks.

The large containers McLean developed are called TEUs — twenty-foot equivalent units — after the containers’ measurements. TEUs can move far greater quantities of goods than moving cargo one piece at a time into a ship’s hold, a long-used method known as break bulk. Today, there are more than 20 million active TEUs, and 90 percent of the things you purchase, including food, have spent time in a shipping container. According to Rose George, author of “Ninety Percent of Everything,” many of the largest container ships have the capacity to transport one banana for every person in Europe.

The modern intermodal system — moving containers from ships to trucks and back again — brought us more food at less cost. But it also resulted during the last century in unintended consequences, such as once-diverse agricultural regions shifting toward monoculture and commodity farming.

Once the full intermodal system opened up, the American diet, though more diverse because of an increased variety of food being transported, started to become standardized. The food sold in a grocery store in one part of the country looked a lot like the food sold in every other part of the country, but few people realized that infrastructure was what was shaping their diet.

BIGGER BOATS, BIGGER PORTS

As more containers came into circulation, an interesting trend began to appear. Instead of building more ships, companies were building larger ships. For the companies, this meant significant cost savings. For the canals and ports, it was one never-ending (and expensive) nightmare.

Without much regard for existing infrastructure, ships have continued to balloon in size, and if they can’t fit through one canal or port, they are then routed to another port that can accommodate them, creating a fairly tidy demonstration of supply and demand.

This competition has led to intense spending across the world to accommodate ever-growing cargo ships. Ports are dredging land under water to create deeper channels to the docks. They are buying larger cranes and investing in automated technologies, including driverless vehicles called AGVs (Automated Guided Vehicles) and automated straddle carriers that can move containers around a terminal. Some ports, like the one in Portland, Oregon, are struggling to stay profitable because they can’t keep up with the growth of the ships.

Likewise for canals, there’s a very real urgency to update because they feel the pressure of competition too. Though it’s convenient, a ship doesn’t have to take the Panama Canal. Those coming from Asia to the United States can go through the Suez Canal, which completed its own expansion in 2015, adding a second shipping lane and deepening the existing one to allow for increased traffic and larger ships.

The Suez Canal isn’t the only other option for a shipping company. Melting ice has led to the development of arctic shipping lanes, and all eyes have been on Nicaragua, where a second Pacific-Atlantic canal is in the works. A slump in the Chinese economy has slowed the development of the canal, spearheaded by Chinese billionaire Wang Jing, but if the project can regain momentum, it will represent one of the largest earthmoving projects in history, employing 50,000 people. For context, the Panama Canal is 48 miles long, 15 miles of which is Gatun Lake. If the Nicaraguan Canal is completed it will be 170 miles long, with 66 miles on Nicaragua Lake.

When Panama saw its capacity ceiling approaching and ships widening, authorities made the call to add a third, wider set of locks. Almost immediately, ports, especially along the Eastern seaboard and Gulf Coast, began planning the improvements they’d have to make to attract more traffic.

The Port of New Orleans spent nearly $40 million to expand container handling capabilities, according to Director of External Affairs Matt Gresham. As reefer technology has improved, so has the demand for storage of these refrigerated containers. The Port of New Orleans spent $7.9 million to build a container racking system that can store 600 refrigerated containers, many holding imported bananas or poultry ready for export.

The Port of Miami is also hustling to attract the big ships. Last year, the port completed a dredging project that deepened the port by 50 feet, which allows them to service ships up to 22 containers wide. With this kind of volume, the Miami port is poised to become the primary entry point for products from South America, which would then be loaded onto trucks and distributed across the country.

These expansions are well-grounded. The Panama Canal expansion is going to unlock a huge amount of volume with roughly the same number of ships.

But the canal expansion and port renovations are still not enough for ships like Maersk’s Triple-E class and several Mediterranean Shipping Company vessels, which are among the largest container ships in the world. In 2014, the China Shipping Container Lines launched the CSCL, a container ship with a capacity of more than 19,000 containers. These newer, larger ships can load more containers, travel faster, and provide greater fuel efficiency. Bigger ships mean bigger capacity, and it’s easier to build a bigger ship than to dredge a port or expand a canal.

Farmers in the U.S. have also been pushing for port renovations and canal expansions because they know those changes to the supply chain infrastructure will mean more buyers for their goods. In 2011 China moved ahead of Canada as the largest importer of U.S. agricultural products. During 2012–2013, the U.S. provided almost a quarter of all agricultural imports to China. A significant percentage of those imported agricultural products are grains. The canal expansion is of particular interest to companies facilitating the shipment of those grains from the Midwest, where many of them are grown. And it appears that most developing countries will be net food importers due to rising incomes, lagging infrastructure and agricultural practices.

REEFER SHIP

A reefer ship is a refrigerated cargo ship; a type of ship typically used to transport perishable commodities which require temperature-controlled transportation, such as fruit, meat, fish, vegetables, dairy products and other foods.

LABOR DISPUTES

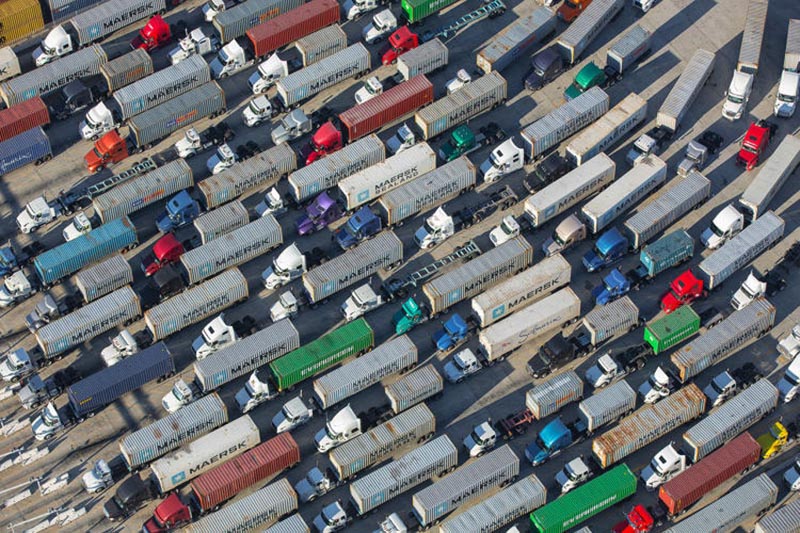

Labor disputes frequently bring intermodal shipping to a halt. In early 2015, dockworkers practically shut down nearly 30 ports along the West Coast of the United States, leaving dozens of cargo ships stranded all up and down the seaboard. This didn’t only mean that goods, including perishable foods, were floating offshore: It also meant that U.S.-grown food was rotting while waiting to be picked up.

The 2015 dockworker labor dispute forced a backlog of trucks at the Port of Los Angeles, where hundreds of trucks and dozens of cargo ships waiting to pick up and unload freight. This port, along with the port in Long Beach, handle more than 40 percent of goods entering the U.S. and almost 30 percent of its exports. Images by Mike Kelley.

EXPANDING A TASTE FOR GLOBAL FOOD

Expanding the canal will shift where ships dock, but it won’t shift our palate or our consumption levels, experts say. America has plenty of food. We import food because we like variety and we demand it all year. Not long ago, finding a fresh pineapple during a Minnesota winter would have been a miracle, but now, you can find plenty of them on produce shelves just about every day of the year.

The expanded canals will increase this kind of globalized eating in other places in the world. Asia’s consumption habits, for instance, have changed tremendously in the past 20 years, with per capita consumption of rice decreasing and consumption of wheat, protein and convenience food and drinks on the rise.

In building the interstate to unify the country, we created immense opportunities for trade while implicitly encouraging product standardization and the dissolution of regional mainstays. Ten general stores have given way to one central Walmart. States have become known for farming only one or two commodities. The same gas station burritos are sold along all 2,460 miles of I-10. These things aren’t inherently bad — except for the burritos — but they represent a shift in cultural values made possible by expanding infrastructure.

We’ve seen the interstate system revolutionize how we grow and transport food. We’ve seen reefers, shipping containers, ports and canals guarantee a consistent supply of produce from tropical countries. Alternatively, we’ve seen the food we have grown and the diet we created packaged up and exported to other countries through those very same channels.

Time will tell exactly what happens after the third locks — and maybe the fourth — open in the Panama Canal, and whether the Chinese-built Nicaraguan Canal, if completed, will turn everything that we know about canal economics on its head.

The Panama Canal expansion won’t show up on the average American consumer’s grocery receipt. The cost savings will be eaten up by shipping companies, and though your mango may arrive a day earlier, you won’t know it. That’s the way it’s supposed to be, but with our growing interest in food and where it comes from, maybe we’ll demand more transparency from a system that thrives on invisibility.

Meltdown, Roman Style

Licking a naturally made gelato in the heavily trafficked city of Rome only takes a few euros. But for its producers, making and moving gelato around Rome is nothing short of miraculous.

Penelope Cruz and her daughter were in Rome last May, and like everyone who visits Italy’s capital city, they wanted gelato.

So they turned to the guy who knows it best, Nazzareno Giolitti, president of the always-buzzing Giolitti gelato shop just steps away from the Pantheon.

Giolitti sat at one of his shop’s coveted outdoor tables, his black polo shirt, white hair and royal blue glasses perfectly matching his blue and black Lucky Strike box. Between sips of espresso and the occasional interruption from his telefonino, Giolitti boasted again and again about the statesmen and actors who visit his shop. Impressive, yes. But he was far less interested in discussing the quotidian set of miracles accomplished by his vast network of purveyors, deliverymen and chefs as they create homemade gelati for more than 2,000 customers a day.

“Rome is a chaotic city. It’s also the most beautiful city, so we pretend not to notice the problems,” he said.

Giolitti’s family started selling gelato in 1906 and opened this location on Via Uffici del Vicario in 1930, making it the oldest Roman gelato shop still in operation. The gregarious fourth-generation gelataio grew up in this elegant cafe, with its high ceilings and white-clad waiters, all of which feel a bit too serious for its clientele.

“It’s difficult,” said Giolitti on running a gelateria in a city with strict traffic regulations and regular strikes and protests. Driving is a real challenge. “But for those born into the chaos, it’s less difficult,” Giolitti explained.

Because Giolitti sells so much product, he receives daily deliveries of milk and eggs from trucks that double-park outside his shop. For the most part, these shipments arrive without a hitch. But when there are impenetrable strikes or heavy traffic, Giolitti gets the call from a frustrated deliveryman. That’s when he sends his motorino out to pick up the product himself.

Once a week, Giolitti drives 30 minutes northeast of Rome’s city center to buy fresh fruit and spices at the Centro Agroalimentare Roma (C.A.R.), the largest wholesale market in Italy and the fourth largest in Europe. The massive 346-acre market in Giudonia looks more like an airport than a place to buy fresh produce.

Each morning, seven of Giolitti’s employees use these ingredients to produce roughly 800 kilos of gelato a day. Most of the gelato is consumed at the shop, but Giolitti also delivers gelato to select restaurants and, if he needs a favor, friends in high places. To transport it, he uses furgoni, or vans sized to maneuver the tight streets of Rome better than the average truck.

“Parking tickets are always a problem,” said Giolitti, “but they are part of the job.” He’s able to keep these 70-euro violations to a minimum thanks to an annual 1,500-euro pass that enables him to move around the city center.

When important statesmen come to town, local officials try to close down Via Uffici del Vicario. Giolitti has to remind them that tourists come from all over the world to visit his shop. They expect it to be open. “So we offer the vigili (traffic police) free gelato,” he said with a smirk.

Giolitti compares Rome’s gelato industry to the tale of its rougher neighbor, Naples: “So many people conquered it and then left,” he said. “The ones left behind, they’re the strongest.”

Giolitti’s old-school approach of selecting produce at the C.A.R. and having milk and eggs delivered daily is too much trouble for the majority of gelato shops in congested Rome. Instead, they spin gelato on site using pre-mixed powders, which can be bought in bulk and have a long shelf life. This also means never having to turn customers away because an ingredient didn’t arrive on time.

“Before the war, gelato was a special treat — you needed access to a cow and you needed really expensive ingredients like sugar, fruit, nuts and chocolate,” said Elizabeth Minchilli, an American expat-turned-Roman food expert who leads food tours around the city. “Once these machines and products were designed, it enabled everyone to make ice cream with the push of a button.”

Minchilli sipped a Negroni and nibbled on peanuts at a trendy bar near her Monti home. The intense, auburn-haired St. Louis native met her Italian husband in her early 20s and settled here, where they raised their two now-grown daughters.

Most of the fruit used in Giolitti’s gelato comes from one of the 85 wholesale produce vendors at the 13-year-old Centro Agroalimentare (C.A.R.), a 346-acre market just outside of Rome that is the largest wholesale market in Italy and the fourth largest in Europe.

Rome’s food system depends on small, nimble methods of transportation, from the furgone truck to the three-wheeled ape and the ubiquitous motorino. Piaggio’s popular Vespa (which means wasp in Italian) is a popular motorino brand.

She explained that a major challenge for Roman businesses is the zona a traffico limitato (ZTL). Rome’s is the largest traffic limitation zone in Europe, meant to keep the historic sites free of pollutants, to encourage public transportation and to reduce traffic.

For the most part, general traffic is restricted from the city center between 6 a.m. and 6 p.m., which causes a rush just before and after, and makes on-time truck deliveries difficult.

But it’s not only the traffic, explained Minchilli. The mayor of Rome is trying to clean up government corruption, but in doing so he’s instigated a “white strike,” where employees do the minimum work required by their contracts.

This means potholes in the roads aren’t being fixed, and if you go to an office to contest a parking ticket, no one is there to help you. “The bureaucracy makes things hard,” said Minchilli.

It’s no surprise, then, that roughly 90 percent of gelato makers are eschewing tradition by using commercially made powdered bases in those push-button machines.

But, as long as that machine is on site, Minchilli said, the gelateria can call itself “artisanal.” This makes it difficult for consumers to know that they’re really eating processed powders.

Gelati made from powders are often overly bright in color. Impressive to look at, but, many argue, not as good as fresh gelato made from whole ingredients.

Overcoming delivery and distribution hurdles while still making ice cream from top-notch ingredients is what prompted Maria Agnese Spagnulo to start her unconventional gelato company, Fatamorgana, 12 years ago.

Maria and her husband, Francesco Simon, realized that in order to use the quality of ingredients they wanted while still selling gelato at a fair price, they needed to create their own economy of scale.

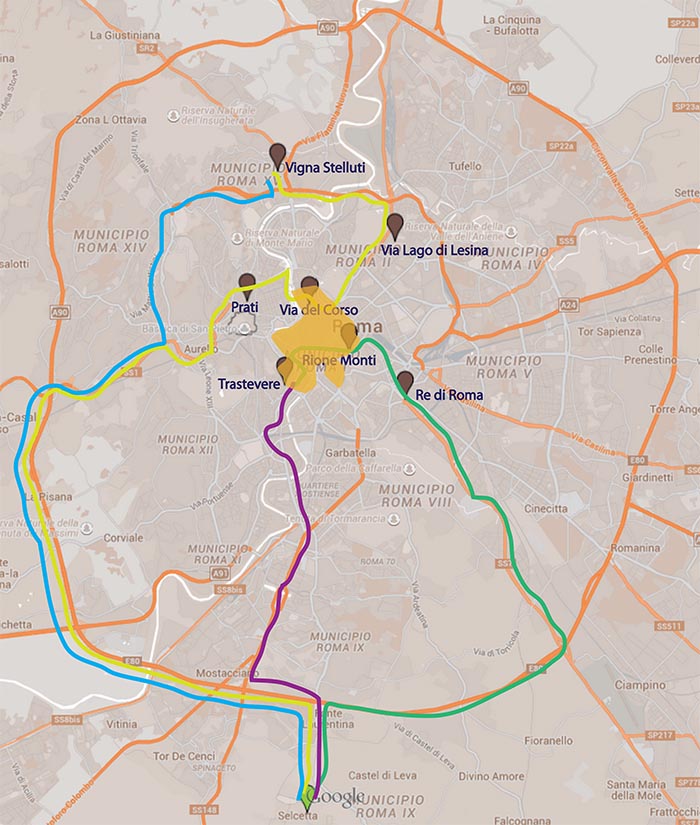

Unlike Giolitti’s traditional model, Spagnulo makes all of the gelato for her seven stores at a commercial kitchen in Trigoria, which is southwest of Rome’s city center and just outside the Grande Raccordo Anulare (GRA), or the “Great Ring Junction,” a 42-mile toll-free highway that encircles Rome.

Spagnulo set up her workspace outside the GRA so that she could easily access her stores within Rome. When you’re within the city, it’s harder to get from point A to point B. But when you can move around the GRA and enter at different points, it’s a lot faster, she explained.

Faster, sure, but this sensible method of distributing one of the freshest gelato products in the city does not qualify as “artisanal” like those powdered packets mixed on site, explained her fast-talking husband.

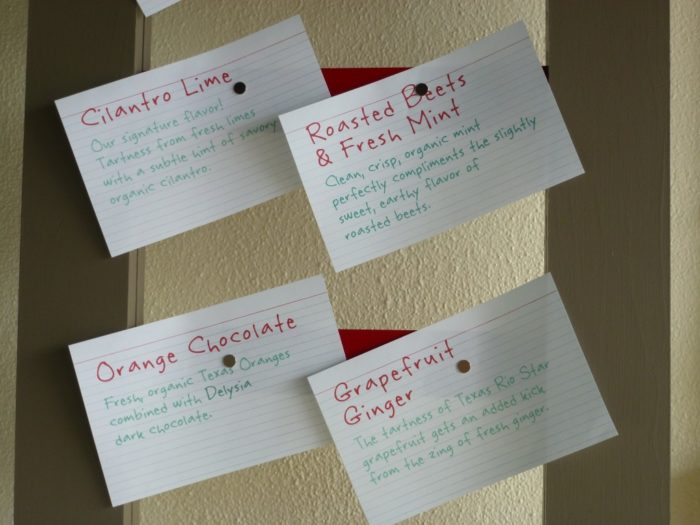

What customers might not know is just how obsessed Spagnulo is with ingredients. Her gelato base contains only milk, cream, sugar and flavors that come from whole ingredients such as saffron, hibiscus flower and lapsang souchong tea, to name a few. She uses these components to make some unexpected flavors such as Sorrento walnuts with rose petals and violet flowers or chocolate gelato with Kentucky tobacco leaves.

Every day, Fatamorgana’s main kitchen receives a milk delivery from Parmalat, one of the country’s largest dairy companies. For fruits and vegetables, Spagnulo goes to farmers’ markets three times a week to meet with producers. Sometimes she’ll schedule a delivery; other times she’ll carry them back in the company furgone.

For some ingredients, like the prized Bronte pistachios, she orders in bulk directly from a Sicilian farmer. Simon explained, “if the pistachios from Bronte don’t arrive, guess what, we don’t have pistachio gelato that day, and our clients understand that.”

Every day, Spagnulo makes just enough gelato to fill the cases of all seven ice cream shops. At the crack of dawn, two furgone, each fitted with a -22° Fahrenheit freezer cabin, deliver gelato.

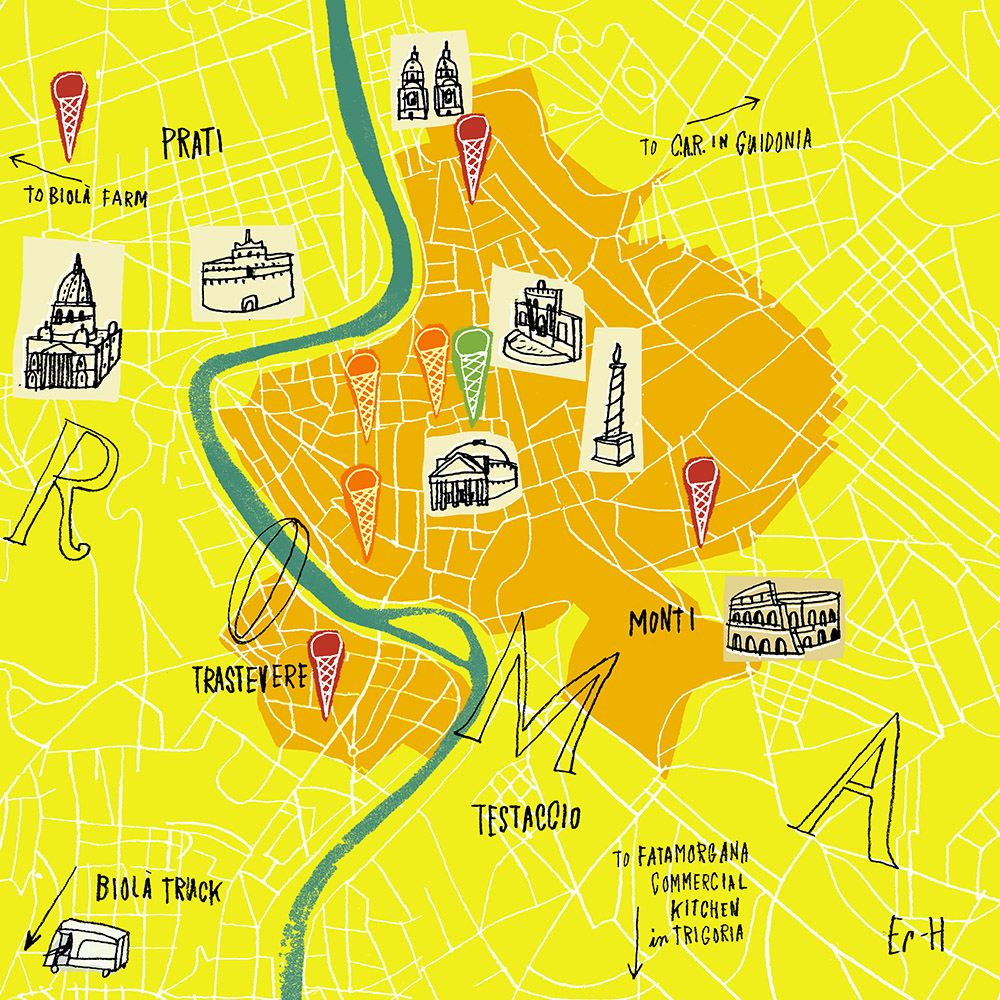

The orange area in the center of the map at left indicates Rome’s ZTL, or traffic limitation zone. Unless you have a special ZTL pass or are a resident you cannot enter this area of the city at certain times, which makes it difficult to deliver goods to shops, markets and stores of all kinds. The green cone is Giolitti. The red cones are Fatamorgana. The orange cones are Grom.

Simon explained that even with a pass to enter the ZTL, delivering gelato to the shops is fraught with challenges. “Before six in the morning, it’s pretty reasonable to get things around Rome,” said Simon. But by the eight o’clock rush hour, “it’s a mess, and from eight-thirty to ten, it’s a disaster.”

A few of their stores are located near 30-minute loading and unloading zones. “But when those are not available, we double park in true Roman style,” Simon said with a smile.

This mid-sized gelateria figured out a profitable model that allowed them to open several stores throughout Rome — so successful they’re discussing the idea of expanding to the U.S.

A gelateria that faces similar challenges to Fatamorgana, but on a much larger scale, is Grom, which has 55 stores in Italy, seven of which are in Rome. Despite their size difference, both companies are reinterpreting how natural gelato can be made, distributed and marketed.

Grom’s liquid gelato bases are all mixed in their Turin production facility from fresh ingredients — high-quality whole milk, as well as free-range egg yolks and many fruits from their own organic farm, Mura Mura, about one hour southeast of Turin in Costigliole d’Asti.

These bases are then frozen and shipped weekly in freezer trucks to their numerous locales. Once the gelato bases arrive at the shop, they are thawed and immediately spun into a rainbow of frozen confections that greet customers by 11 every morning.

Farmer-gelato maker Giudo Martinetti and CEO Federico Grom have grown their business from 19 stores in 2007 to 62 in 2015, including outposts in Dubai, Osaka, Jakarta, Paris, Los Angeles, Malibu and New York.

As a result, some of their products have changed to meet the demands of such expansion. When they first opened in 2003, they sourced the famous whole pistachios from Bronte that Spagnulo uses. They’ve since switched to using Tonda Gentile pistachio paste and pistachio flour. Their success, however, has allowed them to launch an organic farm and a bakery that makes homemade cones, a rarity even among the best gelato shops. To get a sense of how this new gelato model works, I squeezed into the company ape (pronounced AH-pay) next to Daniele Piva, a bearded, 20-something salesman.

Ape means “bee” in Italian and refers to the three-wheeled miniature trucks (about the size of a Smart car) that shuttle all kinds of products around the city. Like motorini, apes don’t need permits to pass in and out of the ZTL, which is one of the main reasons that companies like Grom use them to move supplies. Our job was to deliver dry goods like napkins, spoons and cups to the company’s three heavily trafficked stores at the Pantheon, Piazza Navona and Campo dei Fiori.

This was my first ride in an ape, which handles the road more like a Vespa (a moped that means “wasp” in Italian) than a car. We rolled over the uneven cobblestones, dodging the occasional divot in the road and frequent tourist. Motorini and pint-sized cars whizzed past us as we puttered around the twisty roads, crouched in a tiny truck, feeling only somewhat protected from the madness on the streets by thin doors and windows. “You have to have courage to drive in Rome,” explained Piva as I cringed.

Then traffic slowed and brought us to a sudden halt. “In the center of town, the biggest problem is driving around the tourists,” explained Piva, as a group crossed in front of us. Political manifestations and transit strikes usually don’t last for more than a day or two, but they can feel as prevalent as the tourists. “When they happen, you learn to be patient,” Piva said. Unilever, the third-largest consumer goods company, bought Grom last fall, just months after picking up the U.S.-based Talenti. How Grom’s production methods will change under the new ownership is still unclear.

FATAMORGANA DELIVERY ROUTES

The ring road around downtown Rome, called the GRA, helps Fatamorgana deliver gelato most efficiently to its seven stores throughout the city. This map shows the routes their furgone use from their commercial kitchen in Trigoria to their Roman shops and back again. Route #1 (in light green) departs Trigoria Kitchen (a.m.). Route #2 (in blue) returns to Trigoria Kitchen. Route #3 (in green) departs Trigoria Kitchen (p.m.). Route #4 (in magenta) returns to Trigoria Kitchen. Zona a Trafficato Limitato (in orange).

Grom founders, Federico Grom (left) and Guido Martinetti, launched their first store in 2003 with a model that allowed them to control their gelato product but expand exponentially. They just sold their company to Unilever for an undisclosed sum.

Biolà’s grass-fed Jersey cows produce milk, 70 percent of which goes to other dairy companies that bottle and sell it. The remaining milk is sold directly to customers or is made into value-added products.

If Grom and Fatamorgana are trying to make oldschool gelato in a new way, Biolà owner Giuseppe Brandizzi is taking that idea even further.

Brandizzi’s gelato starts at his family’s organic, raw cows’ milk dairy farm just 30 minutes west of Rome, which his grandfather started in 1954 and his father later ran. Today, the third-generation Brandizzi, who considers himself the custodian of his father and grandfather’s philosophies, now runs the farm and Biolà brand.

Over the years and due to its small production, Biolà expanded beyond just milk to sell more value-added products like cheese, yogurt, beef and gelato. Brandizzi only began making gelato a year ago and is hoping to increase production in the coming years due to its popularity and profitability. He can sell a pint for 9 euros.

Biolà differentiates itself further from other gelato companies by selling its products directly to consumers from a mobile freezer-furgone at designated times and locations throughout the week, mostly in Rome’s peripheries. This model was Brandizzi’s creative solution to the Italian law that forbids unpasteurized milk to be sold through a third party.

Unlike his competitors, however, Brandizzi deals with the challenges of raising livestock, producing milk and gelato, and selling the end products. Wearing a plaid shirt and Panama vest with cigarette in hand, Brandizzi walked past his 60 Jersey cows that are the heart of this intentionally small-scale operation. “Cows that are forced to make a lot of milk actually make less,” he explained. “They are stressed and have a shorter lifespan.”

Biolà produces only 500,000 liters of milk annually, which is a small amount compared to the 10 million liters that the nearby Maccarese dairy produces each year. Of that 500,000, 70 percent goes to other milk companies that bottle and sell it. The remaining 30 percent goes into their direct sales of milk and those value-added products.

Anywhere from one to three furgoni drive to various locations each day, making about three to four stops and parking in a locale for a few hours at a time.

Gerardo Della Vecchia, a jovial, rotund man in his 70s who has been working for Brandizzi for 10 years, parked his Biolà van along the busy Via Gianicolense in the Monteverde district just southwest of the city center.

Della Vecchia set his credit card machine on a small wooden table that hung over the passenger side door and opened the truck’s sliding door to reveal the milk dispenser — a mini door that led to the truck’s refrigerator unit. The sign above the dispenser said the milk had been milked at 4 a.m. that morning and should be consumed in just three days.

By 4:30 p.m. the first motorino pulled up. Helmut on, the driver yanked an empty bottle from his miniature trunk and handed it to Della Vecchia, who filled it with fresh milk. Most of his clients knew him by name. “I watched this kid grow up,” he said, after a teenage boy turned to leave with a bottle of milk.

A young woman, who looked as though she had just come from the beach, bought a small cup of hazelnut gelato. It was clear that Della Vecchia had a good rapport with the nearby café, whose owner came out to chat. But for some Biolà salesmen this isn’t always the case. “Sometimes nearby shop owners call the police, and tell us to move on,” Brandizzi said. But when the municipal police arrive to ticket, that’s when he gifts them some fresh ricotta or gelato.

Brandizzi may not serve his gelato to movie stars or heads of state, but as he talked about currying favor with local officials, he wore a smirk similar to Giolitti’s when he described how he makes Rome’s complicated, often messy and maddening, food system work for him. Call it what you will — these little miracles make the world, and gelato biz, run.

Bad News for A&P

George Huntington Hartford and George Gilman, 19th century entrepreneurs, would flinch at this week’s news that the A & P grocery store chain was filing for bankruptcy. The two Georges created the iconic grocery chain in 1859 and built what we now know as the grocery supermarket. They developed the model for grocery stores that sell low-priced food across the U.S. Now, for the second time in ten years, the beleaguered company has less than 300 stores, down from the 16,000 it operated in 1929. The demise of A & P, the oldest supermarket chain, may be the beginning of the end of the big box, super-sized grocery chains.

Similar to the grocery industry, other economic institutions and industries — banks, taxi services, healthcare, and the hospitality industry — are experiencing “creative disruption.” And food distribution is ripe for repair. The local, personal, and transparent is colliding with accessibility, price, and quality. George Hartford and George Gilman, founders of The Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company, led the first wave of destruction by putting thousands of corner grocery stores out of business at the beginning of the 20th century, and now the effective equivalent of small and local distribution centers may be our future food distribution system.

Marc Levinson’s book, The Great A & P and the Struggle for Small Business in America (2011), tells the story of the rise of big grocery chains from the 1920s until the present day — and how A & P became the world’s largest grocery store chain. Levinson tells us how A & P innovated its way to success only to be come under attack for practices that benefited middle-class consumers by making low cost food accessible. A & P couldn’t find a way to re-create itself amidst pressures from low-priced competitors such as Wal-Mart and high-end stores such as Whole Foods.

By the 1950s the company began a long decline into bankruptcy, unable to resuscitate itself after the onslaught of regulations, attacks, competition, and the loss of its founding team. By building a new aggregated, or “combination store,” as the first supermarkets were called, Hartford and Gilman created often aggressive and innovative ways to bring down the cost of food. Buying directly from food producers instead of wholesales, A & P created some of the first discounted grocery stores. They vertically integrated some activities, such as baking their own bread. They contracted directly with farmers who grew crops specifically for A & P and developed recycling systems for packing materials. The consequence of the new A & P model was the demise of the mom-and-pop grocery store in the early 1920s.

These new approaches to food retailing benefited from the appearance of new technologies that directly improved access to food at lower costs. The first commercial refrigeration systems replaced huge blocks of ice and enabled A & P to hold more inventory. Shoppers could buy enough food for one week without returning for perishable meats and poultry on a daily basis. Open access to food products eliminated the need for a shopkeeper, lowering the store’s operating costs. And when cellophane was developed in France in 1909, the new transparent wrapping material made it possible for consumers to see the food they purchased, a development that increased consumer confidence in food safety.

A & P’s new model encountered feisty competitors and the ire of unions and wholesalers. They fought alongside politicians to push against the growth of the supermarket, joining politicians, journalists and industry associations that accused the brothers of “unfair completion.” The excesses of the Gilded Age and poverty left behind in the wake of the stock market crash in 1929 placed big business in the political crosshairs. Franklin Roosevelt, running on his Progressive ticket, set up regulations, oversight agencies, and rules that threatened the competitive advantages of A & P. Roosevelt called the company a “gigantic blood sucker.”

Accusations of “unfair competition” threaten today’s startups. Taxi cab drivers in both Massachusetts and California are among the many threatened by new economies. Taxi companies have united to sue Uber for “unfair competition.” Ironically, unions are cited by A & P as a significant reason for its bankruptcy filing. A & P officers say that union demands for benefit increases are key to the company’s inability to cut operating costs.

But the accusation of unfair competition raises questions about our current economic landscape. Companies have new competitors, often outside of their traditional industry. Wal-Mart competes with Amazon. And Wal-Mart may be competing with itself. Charles Fishman’s 2006 book, The Wal-Mart Effect (How an Out-of-Town Superstore Became A Global Superpower) suggests that Wal-Mart is so big that their practices are no longer unfairly competitive. Rather, the company is so big that it creates its own market forces. Other big supermarket chains, including Kroger and Costco, both cut their costs to compete with Wal-Mart to offer consumers lower prices.

The tension between Big Box grocery chains and small, independent food retailers continues today, fought with digital weapons and by new players, such as Amazon and Instacart. Signs of the disruption of the grocery industry are apparent across several sectors, from UPS to Google. The re-imagined grocery story is taking shape as a response to the newly food-aware customer who searches for healthy food from a transparent, hopefully human or human-like provider. And the landscape for food distribution may look very different in ten years, populated by Amazon, public food lockers, and encapsulated meals. Amazons’ “buy” button brings customers closer than ever before to a virtual warehouse. And the FAA released regulations for drone tests, the mini-aero service.

Hartford and Gilman’s legacy of supermarkets and low-priced food may continue to be with us but in a new incarnation, more as an aggregated virtual supermarket that utilizes high-tech, “last mile” delivery options. Let’s hope that our future food distribution system will continue to provide better food to more people at low prices. And maybe A & P will re-emerge, making George Hartford and George Gilman proud again.

Milan Expo 2015: Big Ideas

While “thought leaders” gather around the world to predict the future of food, Italians are hosting this year’s world’s fair, the Milan Expo 2015. The Italians are using the Expo to burnish its brand as the preeminent leader of food innovation. The Italians came up with the Maserati and the Moka pot, so why not edible packaging and digital delivery of food?

But wait, what happened to French leadership in all things food-related? If you attend the Milan Expo, you’ll be hard pressed to see where France fits in. Of course, since Italy is the host of the fair, the affair has an effusive Italian feel. Eataly has a large footprint, as does espresso, gelato, and pasta. And in almost every detail, from the kiosks to the drinking fountains, you can see the fingerprints of Italian designers.

Nations have used these fairs as a platform for nation-branding, so it’s no surprise that Italy emerges as the new leader of food design, taste, and innovation. No telling what the French will need to do to regain their preeminent position as the arbiter of food. Although a group of young chefs in Paris is rallying the new generation of French chefs, they will have to imagine how to regain the crown for leadership of all things food-related now that chefs in other countries have moved ahead without being tied to a stubborn French narcissism. And, in addition to the new generation of French chefs, French entrepreneurs are finding opportunities to regain their high regard for a blend of art and science in food. This summer, 33entrepreneurs, a French startup accelerator in Bordeaux, France, will be traveling throughout the US with its tour of food startup contests in the areas of food, beverages, wine, and travel. (The organization’s use of “33” comes from its goal of “disrupting the way 33% of the world’s GDP.”) Perhaps these young startups will put France back in the game.

After all, the French launched the world’s first industrial exposition in 1798, in Paris, and established France, in particular Paris, as the leader in food and fashion. Everyone, including the English, attended these events, enjoying food created by French chefs and delighting the French flair for fashion. The French expositions were really a display of how technology and art merged to make useful innovations. In 1885, Jules Burlat described the 1844 fair, noting how industrial art and fine art shared the stage. Almost 4,000 exhibitors crowded the pavilions during the 1844 world’s fair in Paris, displaying the latest inventions in industry and agriculture. Steam was the biggest game changer, giving inventors a new source of power. One exhibitor showed how he used steam to power a seawater-to-freshwater conversion system.

These French fairs launched a succession of world’s fairs, including the famous London Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations London Great Exhibition in 1851. The famous French chef Alexis Soyer set up a restaurant in the midst of the British fair, parading preeminent French gastronomy to the six million attendees.

But the Italians have the stage now and the Milan Expo is well worth attending.

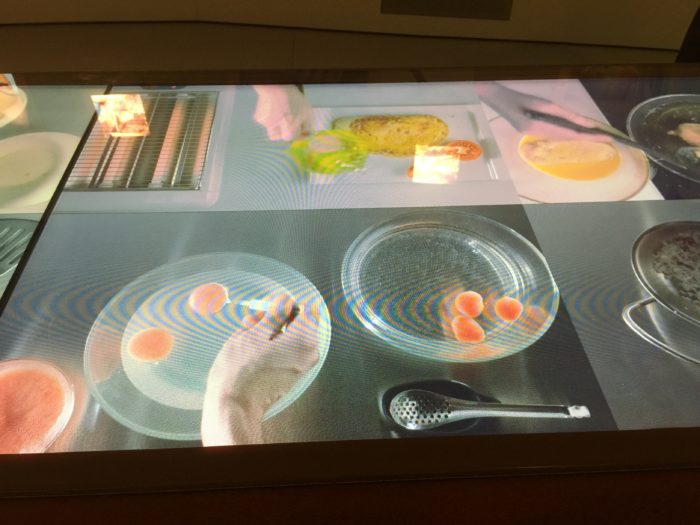

Most of the exhibits are breathtaking. In Europe, where the distances are shorter and the challenges are bite-sized, food innovations are stunning and at the Expo you can see what our food world might look like in 2050. For example, the Coop Market of Italy built a digital supermarket on the fairgrounds. If you want some apples for a snack, you can go to the market, and while you put them into your basket, you can read all about your apples and see who grew them, how they grew them, how the apples traveled to the market, the size of their carbon footprint, their full nutritional analysis, and suggested uses. All this data is stunningly displayed in real-time overhead as you move through the wide aisles. If ever you could imagine how big data might be merged and displayed to create a new transparency of the food system, this moment is telling.

The implications of a convergence of Big Data and Big Food are just beginning to emerge. At the Institute for Food Technologists conference this month futurist Mike Walsh said, “The era of big data will impact not just the production, processing, and distribution of food, but the way that business leaders make decisions.” Seems that your Instagram photos, tweets, healthy metrics, and POS data will shape the our future food system. The data/food mashup will give a digital expression to Anthelme Brillat-Savarin’s infamous statement in 1826, “Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are.”

Other examples of how Big Data will shape an emerging personalized food system is at the McDonald’s exhibit. The new order entry kiosks make the fast food industry minimum wage debate somehow irrelevant. You can watch families crowd around the kiosks while they personalize their hamburgers, adding lettuce and gluten free options as they enter their own orders. A lone McDonald’s staff member stood by a checkout register, the last man standing in the world of mobile payment systems.

A mobile warehouse will deliver your bottle of water that you can sip while watching a mockup of a smart kitchen. The multiple displays and kitchen robots show how your future kitchen may integrate data gathered from your biometric tracking device to design personal food. Your smart kitchen will enable you a comfortable amount of work for you to do with your owns hands with ingredients taken from your pantry inventory that is connected to an online ordering system, connected to the local grocery delivery warehouse. Lots of imagination went into this display. The Expo has a number of displays that take the discussions at the growing number of food-related conferences into the prototyping stage.

The Milan Expo 2015, the international worlds fair with a food theme, brings home the importance of seeing our work in a global context. Innovation outside of the US is alive, fast-moving, and in some ways, ahead of our food innovators. Since countries outside the US, particularly those in Africa and Europe, operate within smaller jurisdictions, they are able to operate without the complexities of multi-state landscapes. That said, the exhibits in Milan are provocative and suggest an integrated, technology-based food system. The Expo was a reminded to think of our work in a global context. Startups and stories need connections to the rest of the world. The next fair, Expo 2017, will be held in Astana, Kazakhstan. Energy is the theme, food served at the fair will be all organic, they say.

A Rare Look at Genetic Diversity in Our Food System

What does a remote Norwegian island 800 miles from the North Pole have to do with our food supply? Much more than you may think. Dr. Cary Fowler, speaking at the American Livestock Breeds Conservancy’s (ALBC) Annual Conference last week in Austin, Texas, explained how the Svalbard Global Seed Vault will protect global crop diversity for the next few millennia. Rarely covered by media and or included in the public debate about our food system, these genetics preservationists are vital to the sustainability of future food production.

Listening to his description of the frigid Norwegian facility were about 75 rare livestock breeders, enduring one of Austin’s coldest autumn days with temperatures plunging into the “horrifying” low of 40 degrees. Gathered in a warm room, these mostly hobby farmers who tirelessly raise livestock such as Mulefoot hogs, gazed at Fowler’s images of a tunnel opening thrust into blue-ish Arctic glaciers.

The president of the ALBC, Dr. Eric Hallman, connected the room full of animal breeders to the business of seed breeding. For the past 40 years, the ALBC has been supporting farmers and ranchers who conserve genetic diversity in domestic livestock breeds as our food system has settled on a few breeds for our world’s large-scale meat production.

The selective breeding of livestock that draws upon specialized animal genetics increases the productivity of our protein supply. This practice has turned over less commercially viable genes to a small group of rare livestock breeders, many of whom were in the room that night.

Dr. Fowler shared his stories about the process of building the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, located on the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen. Working with the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), Fowler led an international team of government agencies, foundations, and private companies to build a secure vault to conserve hundreds of thousands (800,000 samples at last count) of the world’s seeds. The goal is to protect crop diversity against any natural or unnatural disaster. Before the vault was built, many developing countries, some of which are politically unstable, maintained seed vaults that were inadequate. A vault in the Philippines was flooded during a typhoon, destroying many of the country’s valuable seeds.

With predictions that the demand for food will increase by 60 percent during the next three decades, the need for conserving diversity in both crops and animals is critical. The future food supply won’t be produced by these rare breed and seed genetics but instead enhanced and invigorated by these genetics conservationists. Without these conservation efforts, plant and animal adaptations, ever more critical during this time of climate change, will be severely limited. Let us not forget that it was Charles Darwin in the mid-19th century who pointed out the connection between genetic diversity and adaptation.

The U.S. has been involved in promoting seed diversity, also during the inventive 19th century. The predecessor of the USDA, the US Patent Office, began to distribute seeds during the early1800s. The office sent small packets of seeds to farmers throughout the US, inviting them to experiment with the seeds, dispersing and sowing crop diversity, which is still evident today. The farmers planting those seeds created crops that adapted to local and regional conditions.

Because US farmers may have over 50 percent of the world’s wheat genetics, they are increasingly under the mindful eye of the government’s national security agencies. After 9/11 and a sequence of natural disasters such as Katrina in 2005, the USDA and other government agencies saw the protection of genetics underlying our food supply to be as important as the protection the nation’s infrastructure. The increasing sense of international insecurity and the concern about feed our growing world population brings together both the tiny island vault near the Artic and the small group of rare breed farmers listening to Dr. Fowler kindred souls. And while the Svalbard Seed Vault is a monument to Fowler’s astute leadership and international cooperation, these small farmers have no visibility in the current public conversation about food security. We should change this by sending the ALBC a little love.

You can reach them here: http://www.livestockconservancy.org.

Ebola and Your Chocolate Bar

I picked up a few extra dark chocolate bars at the checkout counter today at the grocery store. It never occurred to me that they might be my last in a very long while.

While the human cost of the Ebola crisis is holding our attention for now, other consequences are on the minds of those who move commodities like cocoa beans around the globe.

Two thirds of the world’s cocoa beans come from West Africa. While Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia are at the center of the current outbreak, other West African countries are on the lookout for the spread of the virus. Among them are the top producers of cocoa beans in Ivory Coast, Ghana, Nigeria, Cameroon, and Togo. Some chocolate candy companies are, as one spokesperson from Nestlé said, “On high alert.”[1]

The flow of cocoa beans to the producers of chocolate bars, not to mention the other cocoa-infused food items, just might find their supply chain disrupted as container ships full of beans are either not allowed to leave their West African ports or refused entry in ports where processors anxiously await their shipments.

Insurance companies try to plan for these acts of God or events beyond their control. Insurance policies call these situations “forces majeurs.” These unforeseen events could completely disrupt the food supply chain until the spread of Ebola abates. At a minimum, the spread of Ebola may delay ships or add to the costs of shipping as procedures are put in place by governments to allow for added security procedures and inspections.

Determining liability for those who operate within the food supply chain will occupy lawyers for years, since it is unclear if Ebola qualifies as an unforeseen act out of anyone’s control. And lawyers from different countries will inevitably resort to their own legal interpretations, only further complicating matters.

For now, I’ll grab a few extra dark chocolate bars when I’m in the grocery store and continue to discover how the world’s food supply chain in connected to almost every other system in our lives.

The Pan in Choripán

Most food in Argentina comes from somewhere else, at least in its earliest forms. Like wheat. Sure, there’s asado, an ubiquitous dish on Argentinian menus that is mostly a mound of barbequed meat. But in Argentina, the mishmash of culinary traditions that exists today reflects a long history of immigrants who left very little of anything that can be called truly Argentinian.

The view that the Argentinian national cuisine is actually a mix of British, Italian, and French food can be galling to some cultural purists. The Scots made significant cultural contributions, such as the introduction of football. The British brought tea drinking to Argentina while the native plants added the local flavors of yerba mate. And the British sailed to the Falkland Islands and the Argentinian mainland during the 19th century, hauling their sheep and cattle along as they established ranches (estancias) that survive today, even if only as useful buildings for a remote resort.

Estancia Christina, where our family spent the Christmas holidays, is one such compound, located in Glacier National Park. Visitors can wander through a museum on the ranch that exhibits shearing and branding equipment hauled to the estancia by John Percival Masters in the early 1900s. He and his family had almost 30,000 sheep and shipped wool to Buenos Aires on railroads built by British engineers. Asado was made possible by those decades of cattle, sheep, and pig importations during those years of British ranching.

Argentina is known for its football world championships, not for its bread. Football fans consume thousands of choripàns at their local stadiums. So choripàn bread, closely resembling French baguettes in taste and flavor, brings Argentina and France together if not for the duration of a rowdy football match, at least for the time it takes to consume a chorizo the sandwich.

Wheat flour, used to make chorizo sandwiches, came from wheat brought by the Spaniards to South America during the sixteenth century. The bread in Argentina is almost exclusively white, a lingering imprint left by Europeans that saw white bread as the signature of upper class cuisine. In January, at the Central Market outside Buenos Aires, dozens of customers waited in line to buy freshly baked French baguettes for one kilo of baguettes for seven pesos. (The Argentinian government has set bread prices at ten pesos per kilo, so wonder the line for one kilo of bread at seven pesos wound around and around the bakery stall that day.)

Argentina got serious about growing wheat after the new nation (established in 1852) built a School of Agronomy in 1875. Soon Argentina exported grain for the first time and began to industrialize the country’s grain production system. Bad weather and crop failures in the early 1900s combined with a lack of demand for grains, a commodity not considered important to those waging World War I. When the war was over and the economic depression ended and workers began to demand protection from those who appeared to profit by the resurgence of grain production.

Today’s wheat market is in turmoil as Kirchner’s government restricts wheat exports, causing wheat farmers to lower production and in some cases move their fields into the more lucrative production of soybeans, which have no limits even though sales are taxed at thirty-five percent. Since farmers want to reap the benefits from the more liberal policy concerning soybeans, they are depleting the soil with the nutrient hungry soybeans.

The wheat farmers that remain in their field soldier on, producing grain for choripàn bread. One mill outside Buenos Aires, Melino Chacabuco, receives shipments of grain around the clock. Chacabuco is a sleepy semi-industrial town of just over 35,000 inhabitants located on the Saluda River, now the Laguna Rocha. The presence of a river must have been the attraction for building a mill, a winding conduit for grain to the mills. Tall smoke stacks, grain storage silos, and cylindrical billboards advertise Chacabuco both as a town and as a mill.

I visited the mill, driving three hours to Chacabubo on a long, flat highway through dusty agricultural towns. At the mill, a long queue of bright red trucks transferred grain from their bellies into the metal grates built into the flooring of the mill delivery courtyard. To show how all these shipments of grain become the refined, enriched white flour used in choripàn sandwich bread, two mill employees met me in the mill conference room. With a display more suited to a foreign dignitary, production manager Juan Rafael Errasti and food engineer Gabriela Benavidez sat at a long wooden conference table, slide projector perched at one end, American and Argentinian flags flanking each other, and a basket of sweet, sticky, shiny Argentinian pastries slowly circumnavigating the table.

Both Rafael and Gabriela explained how their mill made flour, and oh, pet food, a byproduct of milling flour. Molino Chacabuco S.A. was founded by Crespo & Rodriguez, a firm in the early 1900s. Don Tomás Crespo and Don Jose Maria Rodríguez acquired the milling equipment in Chacabuco in 1918.

Inside the old Chacabuco Mill, Rafael and Gabriel talk about their jobs. Rafael revealed that his recent promotion as a manager made him uncomfortable. Trained as a mechanical engineer, he confessed that he knows how milling equipment works, not people. He’s tall with silver hair and is wearing a short-sleeved shirt to keep cool in on this mid-summer day. The warm, damp air smells of ground flour.

Gabriela appears to thrive in her job as a food scientist, a position she has had for the last twenty-nine years. Slowly stirring her tea as she empties a series of sugar packets into her cup, she explained how flour continues to hold her interest. A simple loaf of bread, she says, is not easy to make. Not all grains of wheat are created equal, according to Gabriela, who described all the variances that can occur and all the adaptations and challenges that arise as a result of differences caused by different growing practices and weather changes.

Adding to the complexities of her flour world, she believes that bakers today are not as skilled as in the past, sometimes blundering through the making of bread, inconsistently, often tossing in ingredients without regard for precision or, she suggests, any concern for quality. As a result, Gabriela is in constant contact with her customers, advising, sometimes training them so they can create a stable, consistent loaf. After all, she wants them to stay in business and it’s the flour that will get a bad rap if a customer feels the bread doesn’t taste good.

Gabriela reports to Rafael, who towered over her with his wiry six-feet. Her hair is short and dark brown, drawn back over her face by her reading glasses. Wearing a white lab coat with the company logo on one side, she conveyed the competence of a scientist betrayed, in some moments, by an occasional twinkle and smile. During our tour through the factory, we caught each other’s attention when we approached a large area where the highly-polished wooden floor begged for a tango dancer, or two. Spontaneously, we both mimicked the motions of tango dancing, sliding across the floor for a few minutes undetected by the oblivious males in our group.

Rafael and Gabriela led us into the factory, a collection of buildings adjoining their offices. Winding our way in between the tall silos of grain awaiting the capacious maw inside the largest of the buildings, we began our trek up and down the five floors of 1950s style milling equipment.

The mill was impeccable. The machinery was either emitting soft grinding sounds or energetically quivering and rumbling as flour coursed throughout the different factory floors. Every machine seemed to be either grinding or sifting. In a quiet room shut off from these sounds and vibrations, Raphael and Christina presented a series of trays, each with tiny piles of ground grains in various stages of milling. Trays appeared and were whisked away in a performance designed by a team of millers who displayed the same sort of geeky-ness that you find in a chemistry lab. Christina and Raphael showed, with their small piles illustrating the progressive stages of milling how the grains became 00 or 000 flour, two specifications indicating fineness. (The Argentinians use the Italian system for grading flour according to fineness. The more zeros, the finer the grind.)

And the reveal of small piles of flour didn’t end in the small room filled with flour samples. On each floor, Raphael and Gabriela went from machine to machine, pulling out samples of flour to demonstrate how many times the wheat grains passed through the mill, up and down, back and forth, streaming through Plexiglas tubes, rustling and shaking their way towards some degree of 000s.

The floors, supported by the old columns from the mill’s early years, gleamed. While the columns appeared of recent vintage, the capitols were the old cast iron ones, black and decorative. Great care had been taken by someone in charge of the mill’s history to only patch small areas of the flooring, in an effort to keep as much of the early 19th century underfoot. In spite of the effort to keep the mill’s past intact, modern milling practices and the use of computers to manage every step of the process were evident at every turn. One turn took us to a room where bags of additives awaited someone who would measure out desired amounts of niacin and riboflavin to create “enriched” flour. (Seems like the flour industry spends its time stripping off the outer shell of a grain, removing protein and nutrients, and then replacing nutrients through the “enrichment” process. Must be a reason for this, and it might have something to do with the cultural preference for white bread, like the bread used in choripàn.)

Wheat is one of those crops brought to South America by the same Europeans that Niall Ferguson lauds in his book, Empire. Ferguson argues that the colonizers during the 19th century added to the conquered countries, adding such commodities such as grain, railroads, and cattle. Whether you agreed with Ferguson or not, you see the effects of foreign cultures in every choripàn. Argentinian wheat makes a significant contribution to the global economy and governments are wary of any shortage or distruption to the wheat supply chain. As Socrates said in one of his discussions with Plato, “No man qualifies as a statesman who is entirely ignorant on the problems of wheat.”

And Argentina has been having its wheat problems. How the choripàn will fare is unclear. But just ask any Argentinian if whole wheat or any other bread other than that white wheat bread would be worthy of their chorizo and you’ll get a grimace and denial, all in one motion. And the mill in Chocobuco may suffer if Argentina’s government doesn’t release its protectionist grip on production to allow agricultural industries to adapt to weather and market demand on their own.

On the way back from the mill, I passed through several highway tollbooths where police officers waved cars through, allowing cars to pass without paying any toll. My guide explained that the government passed a law making it illegal for tollbooths to detain drivers for longer than three minutes during peak traffic hours. This seemed to indicate that the government was alarmed that such delays could incite riots or other forms of social unrest. If a few minutes delay at the tollbooth could cause such a reaction, imagine what might ensue if choripàn bread became prohibitively expensive or even unavailable due to a wheat shortage. Beware any government that goes too far, threatening all those football fans with the loss of their beloved choripàn.

A Knish Disruption

OK, it’s just a knish, but a recent factory fire in New York put the kibosh on knishes. While the loss of knish production, 15 million a year from this one factory, is a raw deal for a food producer, the interruption in the knish supply chain illustrates how events such as a factory fire impact our food system.

The factory owners say that they will be making their famous square Coney Island knishes again by Thanksgiving. They will now be in the thick of adaptations that will stress every aspect of their business. The company must find ways to adapt the flow of raw materials that would have been on their way to the factory, dispose and replace perishable ingredients, find, purchase, and install the machine that makes the square knishes, and manage their labor force to minimize the impact of work loss. The impact of the fire is also absorbed by the retail stores that sell the square knishes. Those stores will turn away their own customers or find alternate suppliers, which mostly sell round knishes, a shape shunned by the fans of square knishes.

In spite of this local disruption, centered on one machine, the knish food system will manage to emerge in phoenix-like fashion to deliver delicious knishes to customers who consider the square knish an essential part of their food culture. Gabila, the factory in Copiague, New York, will undoubtedly recover, enabling the owners to plan their long-awaited 100-year anniversary of Gabila knishes.

Relationships

Trust matters. As we study what makes our food system work, we find that enduring human relationships are the sinews that flex when the system is disrupted. Social media may be our new tool for building relationships, but speed may not replace our old, slow method of building trust.

Transactions based on trust make the food world go ’round. Food producers, processors, and distributors depend upon relationships built over time that result in trusted transactions and confidence in credit, quality, and consistency.

Long-term human networks that took much longer to build might be on the verge of being replaced or at least marginalized by our modern digital social networks. Our tweets and Facebook postings tend towards one-way communication, not two-way exchanges. Would you trust a new banker if the only way you could build trust with her was to receive her Tweets instead of meeting her for coffee?

Tom Standage, the author of A History of the World in 6 Glasses, and The Victorian Internet, just completed his latest historical hack of social media, Writing on the Wall: Social Media, the First 2,000 Years. It’s about time. Social media has been pleading for a historical accounting.

Standage posits that digital social media is similar to the old social networks in many ways. Short, informal messages have circulated for centuries, delivered via papyrus, paper, and in social settings such as coffee houses. Social exchanges became the underpinnings of business relationships and often led to trading practices that have endured until recent times.

Those concerned about the future of our food system are building mobile apps and big data assets with the intent to solve food supply problems through the Cloud. And they may be right. And in fact, we can see the benefits of digital farming already with improvements in precision agriculture and the improvements in resource sharing. But how will Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn build the trust so essential to trade and transactions? Will the speed and one-dimensionality of our modern social media provide enough depth to anchor the system during disruptions such as war and economic downturns? I’d guess that repeated handshakes that bring humans together in the same physical space matter more than repeated shout outs to your favorite supplier.

The Big Stink for Farmers

The Radio Lab recently featured a podcast called “Poop Train.” Guaranteed to grab your attention, the title referred to a system used by cities to eliminate human waste water. Surprisingly, we learn from the podcast that it wasn’t until the 1980s that New York City stopped dumping treated human waste into the ocean. Gradually, the treatment facilities improved and the resulting sludge was transported to farmers around the U.S. to dress their fields. Because the costs were so high to transport the stuff, sludge is now being kept nearer New York City, awaiting someone to innovate an inexpensive way to transform human waste to agricultural manure on a scale that makes economic sense.

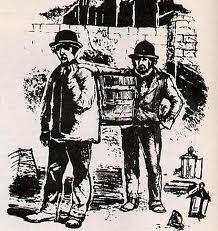

The idea of spreading human waste on fields that produce food for human consumption, although elegantly circular, if off-putting to some. To others, manure is manure. Entrepreneurs in London during the nineteenth century felt the same.

When the London Embankment project was underway, men known as Gong Farmers, transported human waste to farmers outside London for use on agricultural land. When the railroads came to London, Joseph Balzalgette, the engineer who designed the Embankment sewerage system in the mid-1800s, suggested transporting waste on trains to farmers outside London. The history of this enterprise is told in a book by Stephen Halliday called The Great Stink(http://www.amazon.com/The-Great-Stink-London-Bazalgette/dp/0750925809/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1381715168&sr=8-1&keywords=great+stink+of+london). Maybe it’s time to get the topic back on the agenda for urban planners, big stink or not.

Marching on Empty Stomachs

While the world watches Syria cross red lines, Syrians contend with breadlines. Hardly a grenade passes through rebel or military hands without making an impact upon the country’s food supply. Collateral damage inflicted on crops and animals rarely reaches consumers of news about the Syrian crisis.

Throughout history, governments have recognized the link between war, food, and national security. The Romans noticed the connection when they sought food sources throughout their empire; the French saw a revolution ignite over bread prices, and in 1812 Napoleon observed the starvation of his army in Moscow, leading to his famous remark that “an army marches on its stomach.”

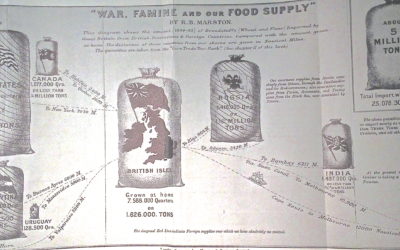

So in 1897, when Robert Bright Marston drew upon Napoleon’s observation to argue for greater food security for Britain, he was well aware of the link between a nation’s ability to feed itself and national security. In particular, he was worried about Britain’s reliance on Russia and the U.S. for wheat and corn. Marston envisioned the construction of grain storage buildings that would enable England to live for three months if a war cut the country off from Russian and American grain. You can see from his illustration how he saw the relationships between grain suppliers and the British grain supplies.

Marston, a British writer known for books about fly fishing, wrote War, Famine, and Our Food Supply to warn Britons that war could disrupt their food supply and somehow bring Britain to its knees. One wonders if urban designers in the early 20th century paid attention to his warnings.

The disruption of Syria’s food supply by civil war has been largely ignored by our media sources but nonetheless grave. While the media talks about casualties from weapons, little is said about deaths caused by famine and poison through the food systems in countries now at war. Few are aware of the destruction of livestock and cropland and the contamination of soil and water over the long duration of some of the modern conflicts.

The ripple effect of unrelenting conflicts is difficult to imagine. The most obvious effect is the breakdown of the infrastructure, especially the transportation of food. In Syria, even the perception of a disruption in the delivery of food causes an increase in black market activity, rising food prices, and higher incidences of hoarding. Pita bread, animal fat, and potatoes quickly disappear into basements and closets. More Syrians freeze and dry food for longer-term storage. As it becomes more and more difficult to transport food to Syria, Syrians look for more localized food sources. Commodities like fuel and flour begin to disappear, creating fears about being able to produce even the simplest but even more essential elements of their diet, flat bread. And, with the potential breakdown of Syrian’s government, comes the loss of state control of bread prices and ingredient supplies.

American cities see the connection between disruptions and urban food supplies mostly caused by natural disasters. New Orleans and New York City are keenly aware of the fragility of food supply chains when a natural disaster such as a hurricane destroys bridges and other food transport networks. In Manhattan, Hurricane Sandy’s impact upon fuel supplies alone immobilized food deliveries.

Cities today are routinely talking about three to five day food supplies, not the luxurious three month supply that Marston was angling for. Whether or not a city needs three days or three months … or three years is a question that needs more attention. Syrians are happy to have three minutes to consume a chemically free meal.

New York wants more than three days of food to keep it afloat in the future. Twelve months would be nice. But who’s to decide and how do we accomplish what Marston argued for in 1897, at least enough food for a country to adapt and find new sources of sustenance?

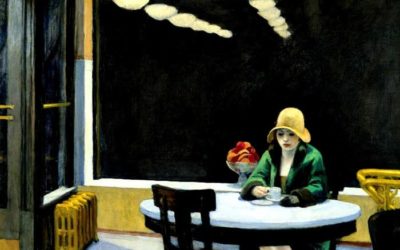

The Art of Food

The Blanton Museum in Austin, Texas, is now showing Sam Taylor-Wood’s 2001“Still Life,” a three-minute video of fruit on a plate, rotting. The time-lapse images are transfixing, engaging your senses as you watch fruit decompose, moment by moment. (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BJQYSPFo7hk)

Food and art have enjoyed each other’s company for centuries. Rudolf Arcimboldo’s 16th century painting, “A Feast for the Eyes,” is an classic art/food mashup. (http://media.smithsonianmag.com/images/Arcimboldo-Rudolf-II-631.jpg.)

Food is also fodder for contemporary performance artists and designers. Marti Guimé’s book Food Designing and Marije Vogelzang’s Eat Love portray food in tantalizing, subversive contexts, turning food as material culture into multimedia, multisensory experiences.

At first Taylor-Wood’s plate of pears, grapes, and apples appears static and your eyes search for meaning, observing the stems and small, brown defects of the pears’ skin. And then, as though taking its last breath, the fruit seems to slightly inflate, inhaling one last time before disintegrating, spoiling, rotting, into a final scene where the fruit, consumed by insects, now white, hoary with rot and spumes of gauzy mold becomes a nauseous disgorgement of putrefaction, amoebic shapes insinuating their original form.

How does a video that includes moving images of rotting fruit acquire the title “still life” in the first place? It’s hardly still or a celebration of life. Or is it? “”Still-Life” is part of a Blanton exhibit that describes ordinary objects that are “beguiling, loaded with narrative and metaphor,” which is another way of saying that the works of art aren’t what they seem to be.

A few years ago I visited the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in Boston. The museum had just moved into an audacious building at the edge of the waterfront and was drawing crowds eager to see new exhibits.

One room included an example of “performance art,” a pile of clothing pushed into a corner. Seemed like the emperor indeed had no clothes, at least at the ICA. By the time I returned home from the exhibit I felt compelled to react to what seemed at the time a display of an artist’s complete lack of creativity. But, for a week, I tossed down my clothes each night and took a photograph. By the third night, I was rearranging the clothing, observing where colors and textures overlapped or where the composition seemed out of balance, overwhelmed by a pant leg or disconnected from an orphaned sock.

The surprise came at the end of the week when I posted the gallery of photos here:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/90414796@N05/sets/72157635382777662/

Aha, I had become the perfect participant in the performance of art at the ICA, provoked to react, pushed to think more about the meaning of art. The pile of clothes wasn’t just a pile of clothes. The exhibit beguiled me, like the rotting fruit, just as the fresh apple beguiled Eve, into believing that clothing had other stories to tell.