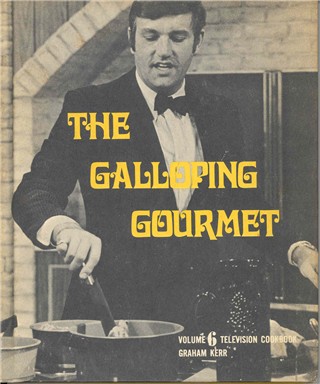

Graham Kerr. The Galloping Gourmet. The man and his brand are inseparable for most of us who got a taste of food programs on TV during the 1960s. Mr. Kerr first appeared on what was known as “experimental TV” on April 16, 1960, before the acclaimed Julia Child made her debut as The French Chef in 1963. But even before the two appeared on TV, Marcel Boulestin, a French chef living in England, appeared on the experimental television programs produced by the BBC during the 1930s. In January 1937, Boulestin demonstrated how to make an omelet for his first program called “Cook’s Night Out.”

Experimentation defined the 1960s, and television was no exception. Early television stations were called “experimental” from the 1920s through the 1950s when broadcast frequencies were not yet commercialized or available to the general public. The BBC’s 1937 program guide reads like a listing of experiments interspersed with articles touting the latest developments in broadcasting technology.

Far from experimental was the decision by both Boulestin and Kerr to begin their programs with an omelet. I asked Kerr why an omelet was the star attraction for his own television debut. He suggested that it was a dish that most viewed as complicated but that, with simple instruction, would enable viewers to achieve a quick victory in their own kitchens.

Watching an omelet take shape during these early years, those who could afford the new Marconi-EMI televisions required good eyesight. The TV had a screen size of only five to eight inches, miniscule compared to our high-definition 152-inch screens.

Why was food one of the first topics to appear through this experimental medium? It may be that the broadcast spectrum became a means for popularizing culinary skills as a way for consumers to save money. Before the WWII, middle class families often left culinary skills to their own chefs or ate at restaurants. The names of the early broadcast programs reflected the idea that a housewife prepared a good meal when her household staff took the night off. And before the war, during the 1920s, books and radio broadcasts included programs that suggested ideas for saving money, such as one program in 1927 called “Wastage in the Kitchen.”

These early years in broadcast are full of experimentation and enthusiasm. Mr. Selfridge, and American entrepreneur who brought Selfridges department stores to England (first one opened in 1909) the focus of a new Masterpiece Theater program currently running on PBS. Henry Gordon Selfridge introduced the first televisions in his department stores in 1927 with John Logie Baird, a Scottish inventor who is often called the “father of television.” Selfridge, an innovative impresario, was much like Graham Kerr, who began his television programs by running through the audience and vaulting over a couch. His wife, Treena, brought her experience in London theaters and pantomimes to choreograph Kerr’s kitchen presence on TV.

These early entrepreneurs, Boulestin, Kerr, and Selfridge should inspire us to think beyond our contemporary food programs and find new ways to popularize culinary skills and good food. Some early efforts are appearing on website and through software applications. But it will be the sparkling personalities and creativity that will engage us anew, much in the way of Julia Child and Graham Kerr.

Author