Food Movers: The Pallet Puzzle

One hundred years ago, on any dock, you could find longshoremen with sore muscles and calloused hands. Many of them would have spent days unloading each parcel by hand from the hull of a ship. Think “On the Waterfront,” but in color.

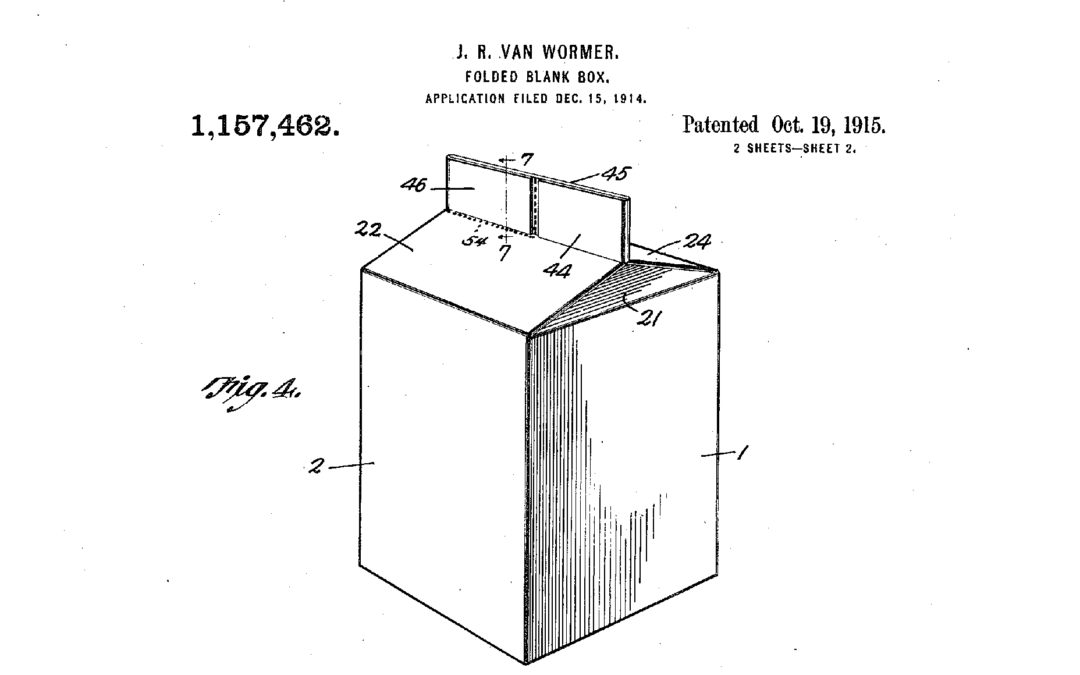

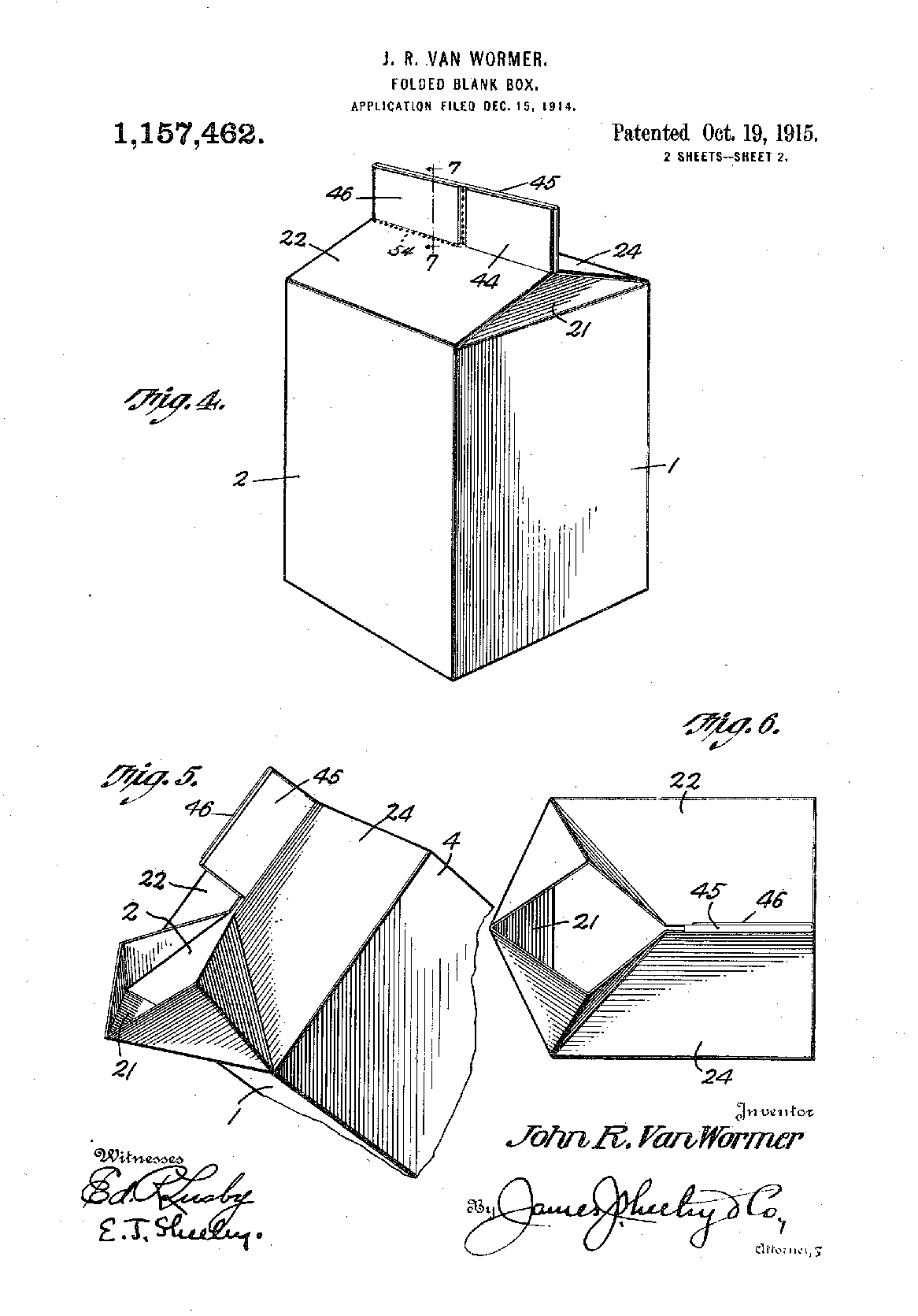

With the introduction of the pallet in the early 20th century, and with its wider use after World War II, what would have taken hours or even days with break bulk shipping — where each item is individually unloaded by hand — took a fraction of the time, allowing more goods to be moved more efficiently.

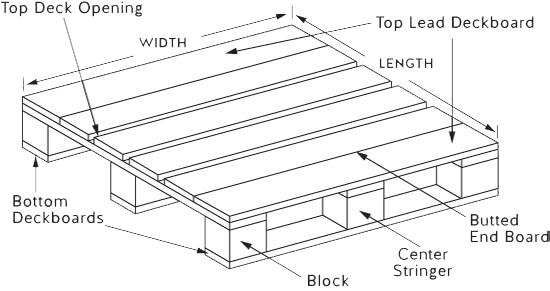

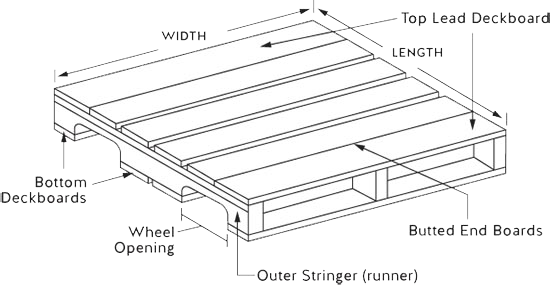

Pallets are platforms, moveable beds of sorts, for just about anything you’d want to ship. Key to their design is the ability of a forklift to pick up the pallet and whatever is sleeping on top of it and put it onto a train, truck, ship or airplane, or move it around a warehouse.

Today, more than 450 million pallets are manufactured each year. In the United States, 2 billion pallets pulse through the channels of the national supply chain — just like platelets through the human bloodstream — carrying vital cargo, often with little recognition of the role they play globally.

Pallets are so integral to the supply chain that they are subject to scrutiny in labs such as one at Virginia Tech, where researchers use stress machines and extreme conditions to test durability.

John Clarke spent 11 years at the Pallet Lab and now serves on its advisory board. He is also technical director at Nelson Company — a manufacturer and supplier of pallets. When it comes to materials, Clarke explains that while some industries favor plastic, steel or cardboard pallets, wooden pallets still dominate.

Ninety to 95 percent of U.S. pallets are made of wood, but even though wood offers affordability and reliability, the porous material risks bringing more than just cargo to its destination. Mold, bacteria and pests can quickly contaminate an already perilous food supply chain. To protect cargo, wood pallets must be sterilized by being heated to 133 degrees Fahrenheit.

“There aren’t many things as old as the pallet that are still made out of the same material as they were originally,” Clarke remarks. “That’s because wood is a very balanced material.” It’s stiff yet strong, cheap yet durable.

Although the 48-by-40-inch pallet is known as the “grocery pallet” for its common use in the food industry and beyond, there is no universal pallet size. Even grocery pallet dimensions are standardized only in the United States. Of the billions of pallets used in the world, there are thousands of sizes, materials and designs.

Some companies don’t own pallets at all. They rent them, creating “pools” of pallets. PECO and CHEP are two major pallet rental companies that appeared on the U.S. shipping logistics scene in the 1990s. As retail chains like Walmart and Costco gained more clout, they began mandating that products from manufacturers arrive on pallets instead of by clamp truck or in smaller loads. PECO and CHEP offered rental pallet services that would save manufacturers that had never used pallets the expense of buying, repairing and retrieving their own pallets.

Although it makes sense for some companies to own their own pallets and use them multiple times, Clarke says that many pallets are never returned to their owners. “You might have a custom pallet, but because of the weight and fuel costs, it’s just not economical to have it returned for ten dollars when you could replace it for five.”

As soon as a company finds a pallet strategy that works, changes in fuel or lumber costs can force another shift in the pallet puzzle.

In high-volume supply chains, all of this fuss over design, calculation and recalculation at the margin matters — especially for time-sensitive, perishable commodities like food. In 2010, Costco decided it would only accept block pallets, with forklift openings on all four sides instead of only two, in the case of skids. This eliminated the need to rotate the pallets if the side without openings was facing the forklift. If Costco unloads millions of pallets a year and saves just two seconds per pallet not having to rotate it, they will have saved hundreds of hours per year.

Pallets remain useful even after their days in the transportation system end. They might pile up outside a grocery store or end up at a special recycling or mulch grinding facility. Thanks to Pinterest, they might get upcycled into a photo frame or coffee table. Useful again, but this time, in full view.

PALLET JACK

another name for a hand-driven forklift that moves pallets; not unlike a dolly.