Markets Go It Alone

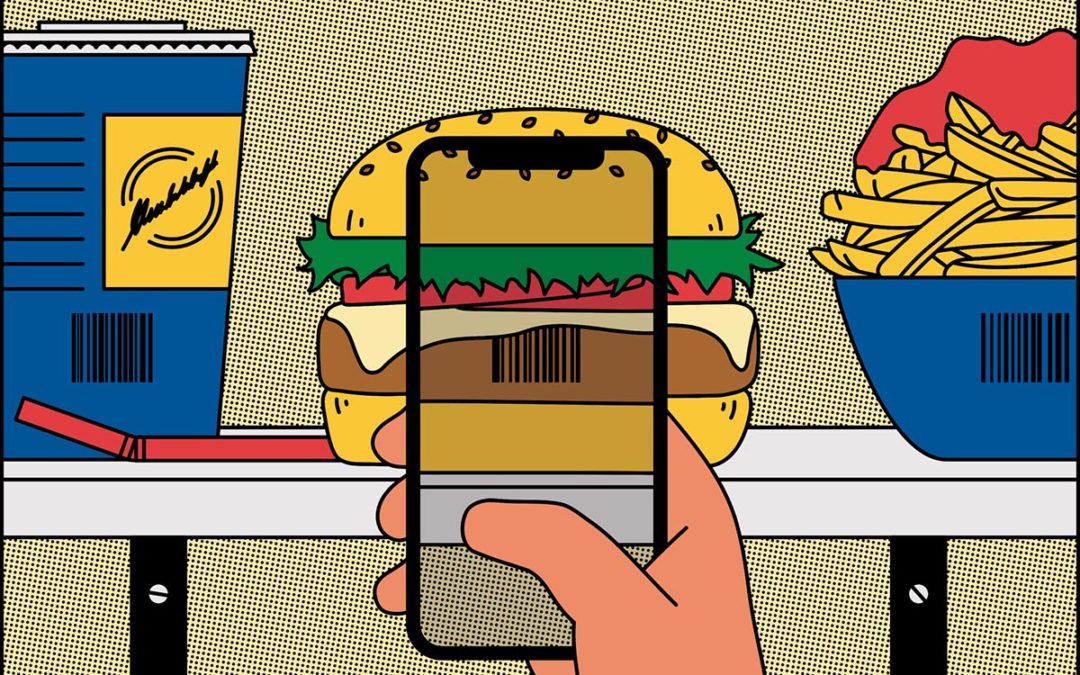

The buzzword for today’s brick-and-mortar retailer is “frictionless.” It refers to a shopping experience where customers can come and go with ease. It means not waiting in lines and never having to take cash or a credit card out of your wallet. Sounds dreamy, right? It’s happening now, and here’s where to find it.

Zippin: San Francisco, CA

When Krishna Motukuri’s wife sent him to Trader Joe’s for a bottle of milk, he came back empty-handed. Why? The checkout lines were too long. When he dug into a study from MIT that found 37 billion hours were lost waiting in line every year, he was stunned. Wanting to help solve this problem, Motukuri took his computer science background and co-founded Zippin.

But while most of us think of the physical store as the end goal, Zippin only wants to be the powerful back end. This month, the startup launched a basic concept store in San Francisco to showcase its technology. To get through the slick entry gate, customers scan a QR code on their mobile phones. Once identified, customers can pick up a can of mango La Croix, a bag of sea salt Boomchickapop popcorn or perhaps a deli sandwich. Soon after they pass through the exit gate, an electronic receipt is sent to the Zippin app. And that’s it. Zippin’s AI-based software platform will allow retailers to deploy a “frictionless” shopping experience that wipes out time spent standing in line. According to Motukuri, operators of physical stores would need only minor upgrades — weight sensors on the shelves and overhead cameras — at a cost of about $25 per square foot. These enhancements, along with Zippin’s software (charged on a monthly subscription) will tell a retailer precisely what has been taken off the shelves.

Amazon Go: Seattle, WA

In January, Amazon opened its first cashier-free store on the ground floor of one of its many offices in downtown Seattle. Called Amazon Go, the store is a free-for-all of convenience foods, meal kits; even beer and wine. As reported by Recode, by being first on the scene, Amazon hopes to “carve out a loyal customer base outside of its website and inside a physical store where the vast majority of food and grocery shopping still occurs.”

Shoppers with the Amazon Go mobile app gain access to the store with a QR code, shop for snacks, take whatever they want and then they “Just Walk Out” — the name for Amazon’s technology. This includes overhead cameras, weight sensors and deep learning technology that detects what shoppers take off the shelves or if they change their mind and put something back. When customers leave the store, the “Just Walk Out” technology debits their Amazon account for the items and sends a receipt to the mobile app. In August 2018, Amazon opened a second location in Seattle. Expect subsequent stores to crop up in San Francisco, Los Angeles and Chicago, where Amazon has already signed leases for two locations including one in the famed Willis Tower.

The Moby Mart: Shanghai, China

While Amazon wants to help us eat more snacks, Wheelys, a Stockholm startup, is developing a market on wheels stocked with hip sneakers, fashionable magazines and yes, milk and cookies. In collaboration with Hefei University of Technology and tech firm Himalafy, the team created a roving, train-shaped convenience store on the university campus, 450 miles west of Shanghai, that can be located using an app. Self-driving, drone-equipped, powered by solar and always open, The Moby Mart is a tech nerd’s space-age fantasy come true.

Wheelys’ foray into automation began with modular-bike cafes. The easy-to-schlepp coffee carts could be moved around Stockholm for anyone not ready to commit to a lease. It was so popular that by 2016 Wheelys had sold 550 bikes. Looking beyond their Nordic country for their next innovation, the founders settled on China because of its large population and the country’s near-ubiquitous adoption of phone payments. While The Moby Mart is still running in beta, Wheelys is moving ahead with what co-founder Tomas Mazetti is calling “magic tech,” or hidden tech.

“At the moment, we believe that hidden technology is the next revolution, not just in retail but in many industries,” Mazetti says. “Imagine walking in through an open door, seeing a beautiful pair of sneakers, trying them on and then leaving the store with them, without ever having talked to anyone or seen any security.”

Farmhouse Market: New Prague, MN

Thankfully, not every automated market is so hands-off. In Minnesota, married couple Kendra and Paul Rasmusson opened Farmhouse Market in 2015. The Rasmusson’s wanted to open a store that offered delicious goods from local farmers, but they knew that staffing a store (and raising their three small children) would be a big challenge. Undaunted, the pair came up with some ingenious ways to run a mostly automated farm store that has some human touches.

First, there’s a membership base — $99 to join and then $20 annually. Members (now in the hundreds) can drop by 24-7 and receive a 5 percent discount on all purchases. Nonmembers can get in on the action at specific hours during the day when there is an actual person behind the counter. And it’s not all that high-tech: Members and farmers use a keycard entry system, and motion-activated lights and tablets enable self-checkout. (There’s a one-theft-and-you’re-banned-forever policy.) The store, only 650 square feet, is monitored with remote cameras, and inventory is tracked digitally. As with every one of these stores, humans are still quite important. Ms. Rasmusson prices items from home and texts orders to suppliers.

Books

Books

Podcasts

Podcasts

Article

Article

Film/TV

Film/TV