Smart Cities Are Forgetting Food

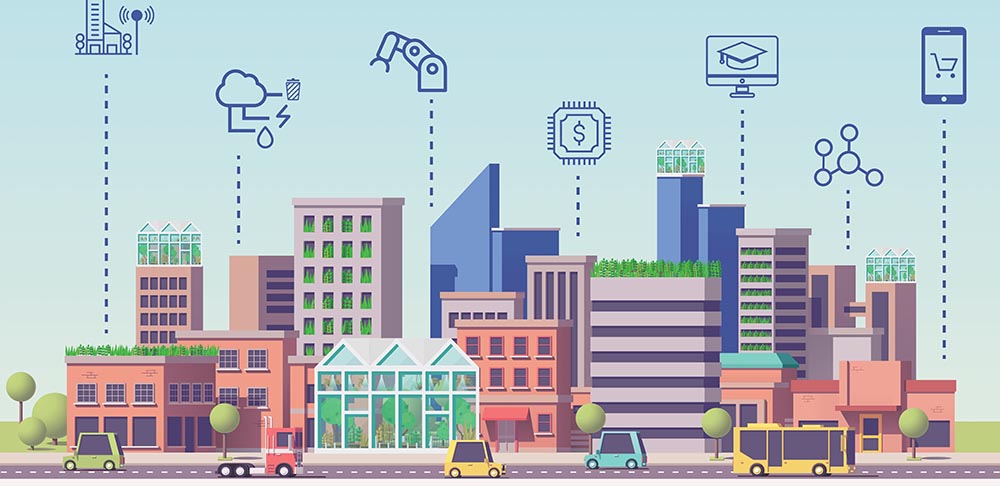

Smart cities use technology and data-driven solutions to make people’s lives better. But until recently, cities have failed to adopt this methodology for what is perhaps the most critical urban system: food. As urban agriculture builds momentum, now is the time for cities to embrace this young industry and foster urban food systems through a data-driven and “smart” approach.

Urban agriculture has the capacity to ameliorate many issues plaguing urban areas. It can contribute to green infrastructure efforts, create a food source that’s safeguarded against climate events and provide a variety of local jobs. But despite the potential of this nascent industry to improve the lives of city dwellers, urban agriculture is often left out of the Smart City discussions and policy decisions that have quickly gained popularity across the globe.

Nevertheless, the urban agriculture industry is growing rapidly as it tries to meet an ever-increasing demand for nutritious local produce. AgriFood Tech investment reached $10.1 billion in 2017, including $200 million in Series B funding for vertical farming company Plenty.

Let’s be clear: Urban agriculture is not the solution to our food system crisis. Other solutions are sorely needed as well, including ways of fostering stronger regional connections between farms and cities. Food waste is also a major issue that needs to be tackled. But urban agriculture is, and will continue to be, an essential component of how every country and city restructures its food system to make fresh food supplies more available, resilient and ecologically friendly.

The author, Henry Gordon-Smith, of Agritecture.

Cities and Agriculture

Just like energy, transportation and internet access, the processes of food production and distribution are integral parts of the urban ecosystem. And like those other system components, agriculture should be supported through smart policies that are data-driven and context specific. The path forward for resilient cities and communities must include thoughtfully planned urban agriculture.

Some cities around the U.S. and abroad are beginning to implement policies to encourage the industry’s growth as a critical part of local and regional food systems.

In Atlanta, for example, a director of urban agriculture within the mayor’s Office of Resilience ensures that municipal support is consistently available to local farmers via the AgLanta digital resource hub, along with a wide range of other initiatives. Through the city’s “Grows-A-Lot” program, Atlanta residents and nonprofit organizations can secure renewable five-year leases to farm vacant city-owned property.

Many other cities have passed zoning ordinances and started programs to promote the expansion of urban agriculture. In Boston, Article 89 comprehensively addresses where different forms of urban farms should be permitted within the city. In Minneapolis, the Homegrown local food program brings municipal and community actors together to research and plan out future supportive policies. In Paris, a municipal initiative called ‘Parisculteurs’ aims to cover the city’s rooftops and walls with 100 hectares of green space by 2020, and to dedicate a third of that space towards food production. And in Singapore, developers are incentivized to include urban farms as part of green building requirements.

But these efforts are largely piecemeal. Few cities, if any, are using data-driven urban-agriculture planning and analysis to ensure future resilience in this burgeoning sector of municipal economies. By performing in-depth analysis on where the greatest vulnerabilities lie within their local food systems, cities can change what today is mostly a feel-good concept into a critical framework that can be scaled to transform local food production. Using data can help determine the best opportunities to bolster urban and peri-urban production to achieve goals such as food access or stormwater management.

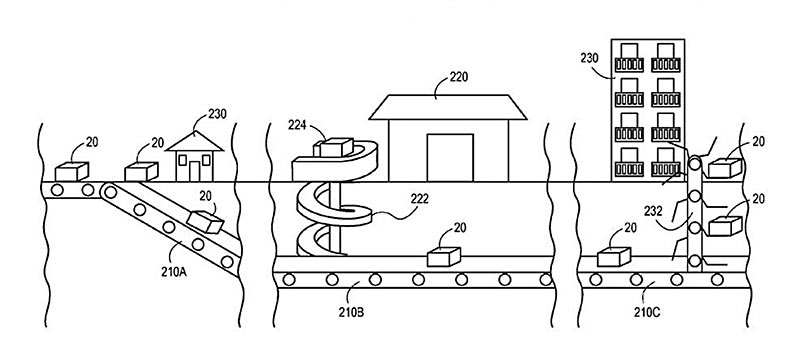

The idea here is not to turn urban agriculture into a top-down model. The decentralized and diverse nature of urban farming models is a major contributing factor to the industry’s rapid pace of innovation and its ability to be a resilient source of food production. Rather, the idea is for cities and regions to understand where the greatest vulnerabilities and opportunities lie within their local food systems, and then to plan out and provide support to targeted areas of the food economy, perhaps through local food distribution hubs and farming incubators for entrepreneurs and startups.

Advances in urban agriculture planning are happening — slowly. Cities and communities are starting to work together across sectors and silos to recognize and promote agriculture’s role as an integral component of smart, resilient cities. But there is plenty of work to be done.

Taking the Next Step

Now, like passionate entrepreneurs first entering the food- system space, many cities have great intentions for urban agriculture. Unfortunately, many cities also lack the capacity and technical knowledge to understand where the local food system should be strengthened to most effectively make it smarter and more resilient against environmental, social and economic stressors.

For cities to become smart in this sector, they no longer need to recognize the many benefits of urban agriculture — that has already happened throughout mayoral administrations, academic halls and even more recently in Congress. The time for putting energy into persuasion is over.

For our part, at Agritecture we have designed a new service called Urban Agriculture Scenario Analysis to assist cities in analyzing and strengthening their local food capabilities. Using site-specific and scale-specific data and modeling, Scenario Analysis can transform a city’s piecemeal farming community into a diversified urban agriculture economy.

The good news: There is a wealth of burgeoning technology around urban and peri-urban food production and distribution. Many urban farms are already “smart,” using sensors and data to tailor everything from lighting to crop nutrition. This is true in large farms such as AeroFarms, which dominates an entire converted warehouse in Newark, New Jersey, and also in smaller farms like Farm.One, which takes advantage of underutilized basement space in Manhattan to cultivate rare specialty crops for the city’s restaurants.

But if cities are going to be successful in integrating advances in food system technology into their wider metropolitan planning efforts, they must apply a data-driven methodology similar to the approach that many urban farmers are taking to more effectively grow crops.

A Smart City revolution is currently sweeping the world. Although we remain in the early stages, this revolution will soon transform the way that cities support the most essential components of urban life. To ensure that food isn’t left out of the equation, cities must start supporting urban agriculture in targeted ways that work with the urban agriculture industry to reconstruct our food production and distribution systems into smarter, more localized and more resilient networks.

Don’t be surprised when you begin to notice your sidewalk cluttered with electronics instead of people. DoorDash, an on-demand food delivery service based in San Francisco, is testing out robots as an addition to its food-delivery workforce. [Read more about DoorDash in our story, “

Don’t be surprised when you begin to notice your sidewalk cluttered with electronics instead of people. DoorDash, an on-demand food delivery service based in San Francisco, is testing out robots as an addition to its food-delivery workforce. [Read more about DoorDash in our story, “