Food Movers: Paper or Plastic

The plastic grocery bag as we know it today comes from Sweden. Working for a plastics company called Celloplast in 1965, engineer Sten Gustaf Thulin developed a technique for sealing a folded tube of plastic and punching out a hole to create sturdy handles.

The polyethylene bag was waterproof, less likely to tear than paper, cheap to make and light to ship — and so cheap that stores have been giving them away since Day 1. Alas, they are so light that they blow into trees, fences and waterways with ease.

These single-use bags that revolutionized the retail world have now polarized it.

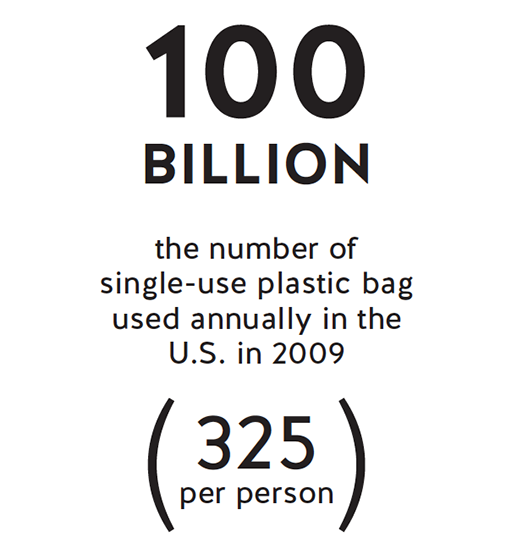

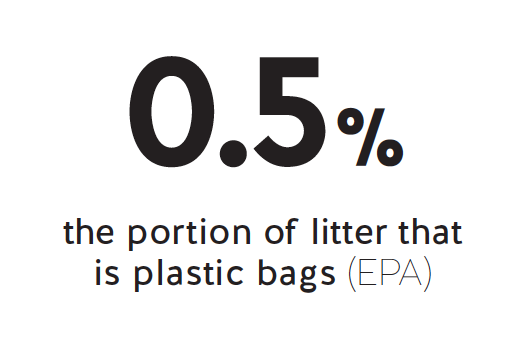

As one of the more visible forms of litter, plastics bags have over the past decade become the target of environmentalists around the world who advocate banning them. Some of the bag bans passed in cities such as Austin have been challenged by lobbyists and lawmakers who argue that plastic bags are more useful than they are harmful to the environment.

Even though bag bans in places like China and California have led customers to reduce all bag use by upwards of 70 percent, critics cite numerous studies that have found that manufacturing and shipping paper bags is two to three times more harmful to the environment than making and moving single-use plastic bags.

For example, a single truck can transport two million plastic bags, but it takes seven trucks to transport the same number of paper bags. That works out to five to seven times more cargo weight on both sides of the chain — i.e., coming to stores as new bags and transported in the waste stream — as well as added greenhouse gas emissions.

Scientists use what is called a life-cycle assessment to determine the global warming potential and environmental impact of how different kinds of bags are made, transported, used and recycled. The United Kingdom’s Environment Agency compared different kinds of bags for a life-cycle assessment study in 2011 and found that you’d have to use a paper bag four times for it to be more environmentally friendly than a standard single-use plastic bag. And what’s more surprising? A cotton bag would have to be used at least 173 times. In other words, because of the intensive resources used to make and manufacture cotton bags, you’d have to use a cloth reusable bag 173 times to have the same environmental impact as a single-use bag.

But there are other factors to consider in that study: Plastic bags are more toxic in aquatic environments, and they break down into micropieces; however, paper bags require more water, energy and chemicals to produce, which can be toxic to the environment during the manufacturing process.

As is often the case, the solution may not be a simple binary choice between paper or plastic. For example, in some countries with bans, such as Morocco, you’ll find flimsy recycled paper fiber bags that feel like soft fabric and are biodegradable, while Canada is leading efforts to create a recycling stream for existing polyethylene bags.

Even if the bag bans don’t last, the effort to use more sustainable, reusable packaging to move our food will continue. That requires changing consumers’ and retailers’ behavior, no small feat in the grocery business.

A cotton bag requires more resources to make and transport than a plastic bag. So many more, in fact, that you’d have to use it 173 times for it to be more environmentally friendly than a plastic bag. But, plastic bags are much more toxic to aquatic environments.