by Food+City | Feb 7, 2018 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

If you want a new experience while visiting an art museum, try going as a food logistics nerd.

Recently, I had this pleasure at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, the home of such luminaries as John Singleton Copley and John Singer Sargent. The two ladies at the front desk, each sporting particularly colorful eyeglasses — one in flamingo pink and the other in cerulean blue — slowly warmed up to my request and began sketching a path through the museum on the printed floor plan. “Go to the Americas room and look for jars. Then go to the Classical Art rooms and see if you can find amphorae,” they offered, visibly surprised that they had discovered something.

For my part, I wanted to hunt down Winslow Homer’s images of fishermen lugging halibut.

Here’s what I found.

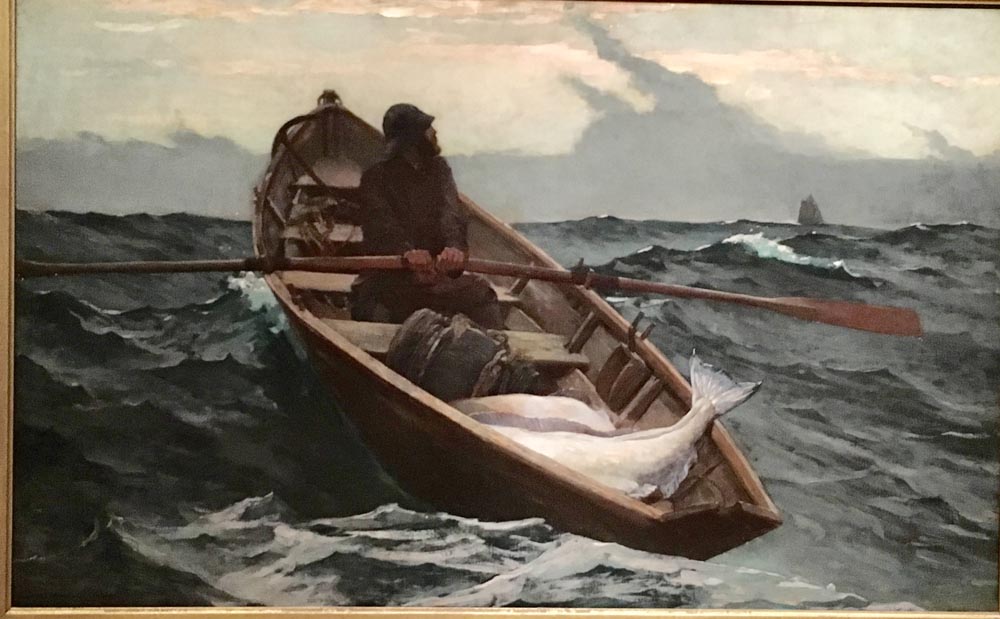

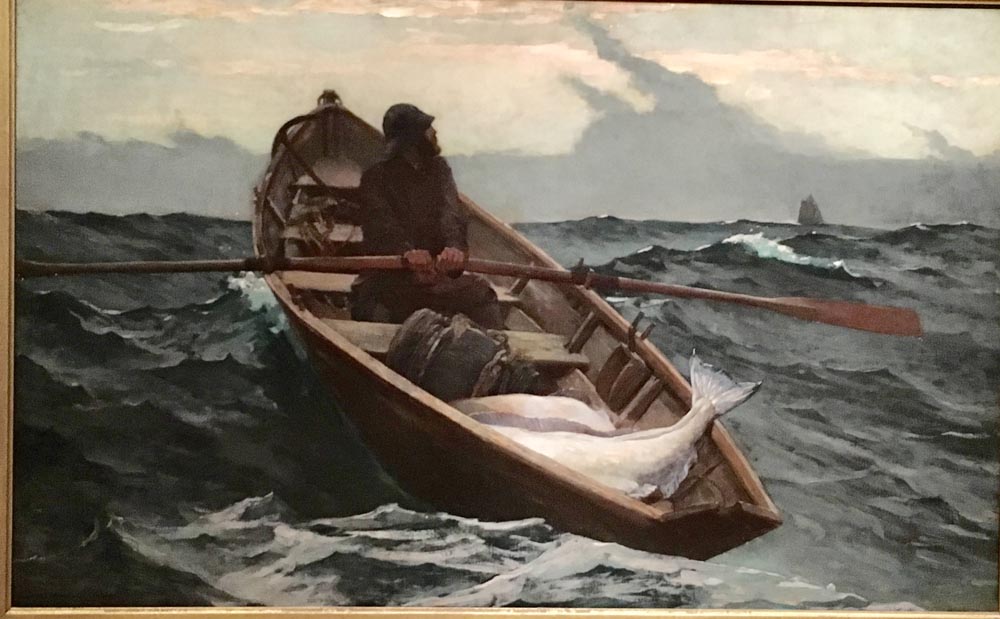

The Fog Warning, Winslow Homer

Winslow Homer’s The Fog Warning, is the dark, foreboding image of a solitary fisherman looking over his shoulder at the oncoming fog bank, his boat weighted down in the stern by two huge halibut. Does he make it home? There’s a schooner on the horizon in the distance. Does he know the ship? Does he reach them? His boat is a fishing dory, a flat-bottomed rowboat that was designed to carry large loads of fish caught at sea.

Salem Harbor, Fitz Henry Lane

Fitz Henry Lane, an American painter known for his ethereal use of light, lived in Gloucestershire, Massachusetts, where images of ships and the fishing industry surrounded him. Salem Harbor, painted in 1853, was the center of the China trade that brought not only silks but also tea from halfway around the world. Square-rigged schooners and other working boats fill the harbor, unloading cargo into the Salem warehouses.

Whaler in the Ice, Chopping Out, William Bradford

You can feel the chill of the Arctic wind in William Bradford’s Whaler in the Ice, Chopping Out. The black and white charcoal image illustrates the slow, cold journey whalers take as they hunt spermaceti and other whale oil to fuel American households and their cooking stoves.

The Wreck of Ancon, Loring Bay, Albert Bierstadt

Albert Bierstadt, the master of romantic, heroic American landscapes, recorded the demise of the ship Ancon, which was stranded on a ledge in Alaska with its cargo of canned salmon. This 1869 oil painting, The Wreck of the Ancon, Loring Bay, captures the fragility of 19th-century food logistics with ship’s cargo at risk of weather, ledges and pirates.

The rooms filled with Greek antiquities included numerous jars and amphorae that held food, water and wine for various purposes — some for rituals, others purely utilitarian. One two-handled amphora from the Archaic Period (540-520 BC) gleamed from one case, displaying figures and grapes all the way around its midsection. As with most Greek vessels, the surface tells an elaborate tale of gods and humans. On this amphora, you see Dionysus (the Greek god of the grape harvest and winemaking) drinking wine while satyrs make more. The amphora illustrates the process of winemaking, including each of the various steps between the vine and your plate. Other, less ornate amphorae transported oil and wine across the Mediterranean in ships’ holds.

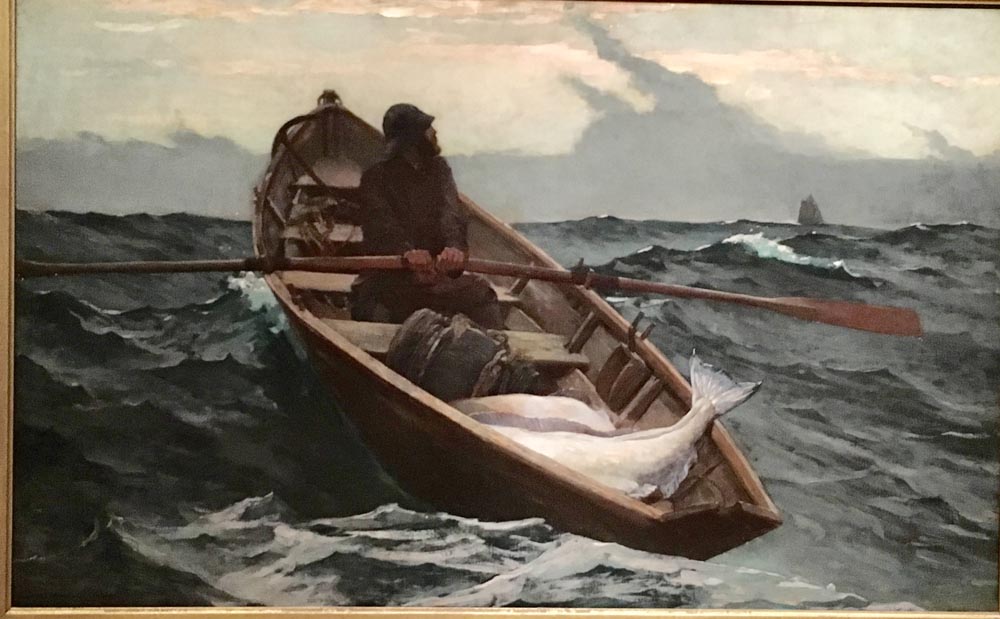

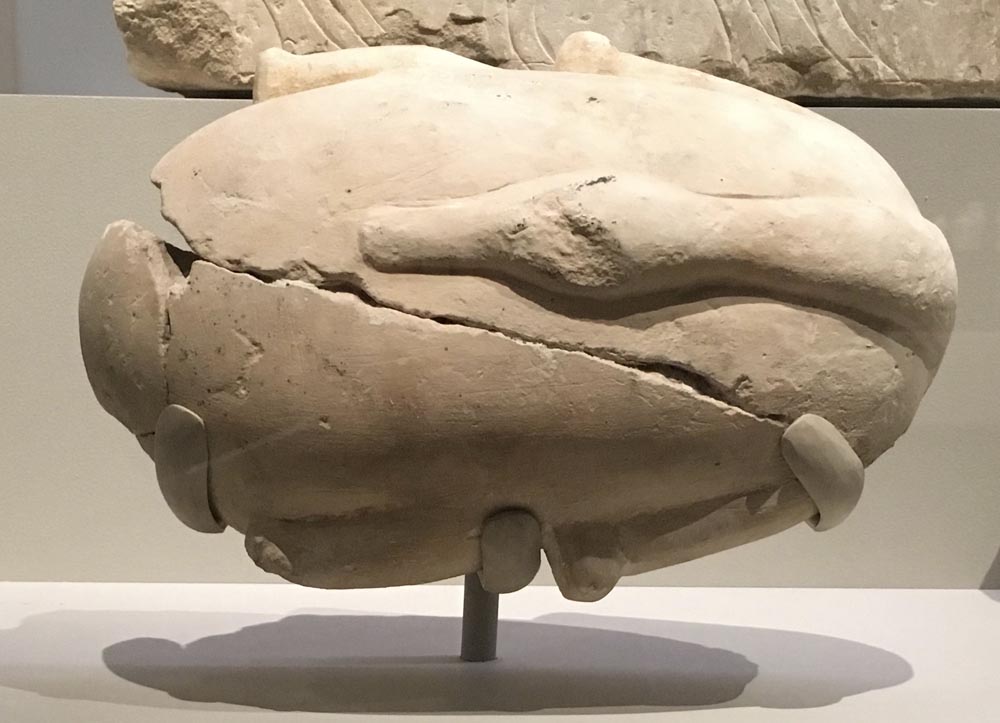

And finally, food transported to the dead is a food supply chain familiar to cultures that believe in an afterlife. The Egyptians assembled elaborate kits for those who departed from their world to the next. These stone containers, often depicting the food encapsulated within, contained the necessary sustenance to survive the next world. Called “food cases,” they were filled with provisions such as beef ribs and bread, sometimes wrapped in the same materials as the individual embalmed inside a sarcophagus. Notice that this one has a duck carved on the exterior, suggesting that a duck breast awaited the departed.

Imagining a museum as a repository of food logistics stories turned up some surprises and even more reminders that transporting food around the world has been going on at least since the Egyptians packed food for the afterlife. Whether in this life or the next, the movement of food can be a combination of art and science, utility and aesthetics. I can’t wait to visit another museum with food logistics goggles.

by Food+City | Jan 31, 2018 | Food Tracks Blog, History, Stories

The Kimball Art Museum portrays a side of the meat business many visitors to Forth Worth, Texas, don’t see. If you only toured the Stockyards outside the museum, you’d miss the preceding centuries of carnivorous history.

In the late 1580s, Annibale Carracci painted two canvases that give us an idea of how meat fit into urban landscapes during Italy’s colorful Renaissance. By the late 16th century, Renaissance art entered the period of Mannerist painting, which led to the Baroque period, when the ideal proportions of High Renaissance art became exaggerated and even distorted. In the early 1580s painting, The Butcher’s Shop, Carracci’s two butchers and their gory background are examples of less-than-idealistic settings and out-of-proportion humans. The animal bodies outweigh the human bodies, and heads become dwarfed by torsos.

Called genre paintings, these images of everyday life stand in sharp contrast to the mythic portrayals of religious figures that hung in the Italian churches. Carracci, in one of his two paintings of butchers (the other, larger butcher scene is in the Christ Church Collection, Oxford, England), shows us one day — any day — in the life of a 16th-century butcher. He knew their lives because several of his family members were butchers in Bologna.

“One looks directly at you in defiant confrontation, as if he’s daring you to accept the reality of his profession with all its gore.”

There are two butchers in the Kimball Museum painting. One looks directly at you in defiant confrontation, as if he’s daring you to accept the reality of his profession with all its gore as he holds out a cut of meat for consideration. The other, eyes cast downward toward his knife, is preoccupied with the work of the day. Carracci studied with Titian in Venice, and the latter’s iconic red spills onto the canvas. There’s no blood on the floor — it’s not that messy — but the hanging carcasses are almost like stage backdrops surrounding the two men as they display their art and prepare for the next animal to slay. Nothing glorified here, but everything to see.

The carcasses suspended from sturdy meat hooks above the two figures appear to be from sheep. One sheep’s head lies at the feet of one of the butchers, one of its eyes cast in the direction of another sheep hanging above, eviscerated and waiting to be skinned.

A beef carcass dominates the left-hand side of the painting, cut in half as is still the custom for wholesale cuts of meat, which today would include all eight primal cuts. (Those are chuck, rib, loin, round, flank, short plate, brisket and shank.)

We can’t tell from the painting if these are retail or wholesale butchers, but both existed throughout Europe at the time.

Outside the Kimball

Outside the museum are the Fort Worth Stockyards, whose story is more familiar for Americans who know about the role that Forth Worth played in the history and development of the U.S. meat industry. The names of Armour and Swift, written in the embankment that surrounds the Stockyards, tell visitors who made Forth Worth the largest feeder of cattle from the Western ranges.

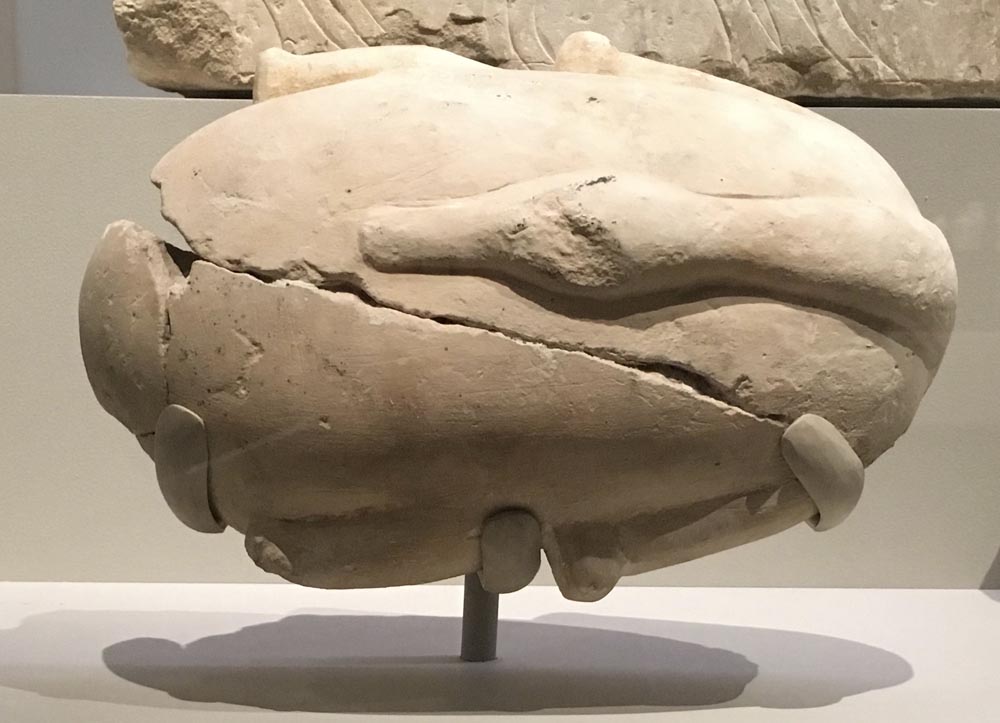

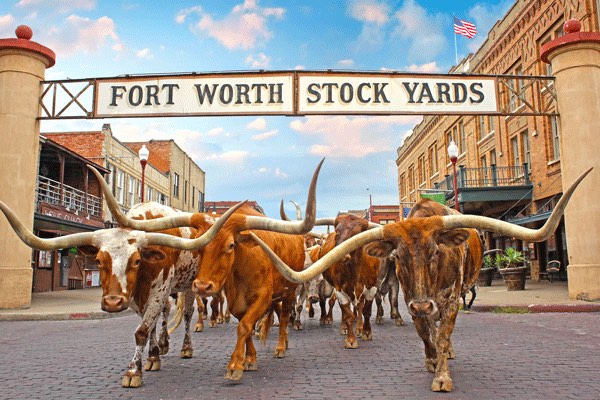

The entrance to the Fort Worth Stockyards, from fortworth.org.

In their new incarnation as a tourist site, the Stockyards entertain visitors with twice-daily reenactments of cattle droving. Texas Longhorns plod silently down the street attended by cowboys located in the traditional positions of a droving team.

Inside the surrounding buildings, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, packing houses practiced the art of butchering in much the same way as those Italian butchers in Carracci’s paintings. Now, in Brooklyn and other foodie destinations, shops like those in the paintings are few but gaining more appeal as consumers demand more transparency between their food (meat in this case) and their plates. Perhaps it’s time for a contemporary painter to record those new Brooklyn butchers — pristine white aprons and all.

by Food+City | Jan 22, 2018 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

Food waste is a messy subject. What can one person’s efforts to record her scraps teach us about reducing our footprint?

Logi, a mythological Nordic warrior, won an medieval eating contest that involved consuming a tray of meat and bones — and the tray itself. (The tray was made of bread in those days, so it’s not such a big deal as it appears.) His gluttonous display was typical of the way men proved they were, indeed, men. The more food consumed, the more powerful the man.

For centuries, now, eating enormous quantities of food has been as necessary among the elite — who use consumption as a marker of social status — as it has been among the poor, who never know when the next famine will occur. The abundance or scarcity of food is one of the world’s paradoxes. We eat a lot, though not quite like Nordic warriors. And at the same time, we waste a lot.

Food waste tops the list of concerns for food system reformers these days. And why not? The UN Food and Agriculture Organization claims that we waste about 1.3 billion tons per year of edible parts of food, or about 4o percent of the food we produce. That’s enough to motivate anyone to reconsider what goes into the trash bin after a meal. The 2013 FAO report, “Food Wastage Footprint, Impacts On Natural Resources,” dissects the mountain of food waste generated each year. Perishable fruits and vegetables occupy much of that mountain for obvious reasons. In spite of advances in food preservation, we haven’t yet found the right technology for eliminating perishability.

“…we waste about 1.3 billion tons per year of edible parts of food, or about 4o percent of the food we produce…”

But before wringing our hands, we should wonder about what constitutes “food wastage,” as the FAO calls food waste. We hear about food waste in the media and at events that reference the same FAO report. As much a consequence of recirculating Internet data, this reliance on a single source can’t be our only source for the war on waste. If the topic is so fundamental to improving our food system, should we be evaluating a range of studies from multiple perspectives? Even without reading the UN report, we might wonder about packaging and about all the leaks along the food supply chain where food becomes waste. Did the FAO really go to a significant number of landfills and weigh all the different types of waste? Might there be other methods for finding food leaks and breaks the food distribution system?

The whole topic is messy. But even without knowing the exact amount of food waste in our food system, I imagine we’d all agree that the problem could use a big solution.

But overwhelming problems often numb our ability to act individually. Wondering what just one person might contribute to heap of wasted resources, I spent a week photographing my food wastage footprint. I became so self-conscious about my food waste that I began eating more trimmings and food before taking a photo, simply because I was embarrassed by the amount of waste that was about to become public record. Being shunned by one’s peers because of an oversized waste footprint could become the next neurosis requiring treatment by modern psychiatrists.

While I worked to overcome the fear of disapproval, I saw that my food waste footprint had grown to the size of Sasquatch by the end of the week. This wasn’t a complete surprise, since the amount of food that I was required to buy in the grocery store was more than one person could eat in a week; remains of a head of lettuce and a quart of milk were all spoiled by the end of the week. Perhaps this is an admonition to never eat alone. More fun and less waste.

While my experiment wasn’t life-transforming, taking the photos did tell an interesting micro-story about one person’s waste footprint.

So what are the takeaways?

I wonder if there is a better way for single people to buy and prepare food. Would more single-serving packaging alleviate the problem? Lately I’ve noticed “Ready to Serve Brown and Wild Rice” from Riviana Foods in packages of two servings, ready to microwave. It might help, but packaging still needs a solution: even my single-serving yogurt leaves me with a foil top and plastic container at the end of the snack.

Would growing my own food lessen the amount of waste, since I could pick just what I needed for a meal and compost the remains each day? Maybe, but that would require a lifestyle change for many of us.

How about portion controls? When I ate out, the waste trail increased. Restaurants, unless you eat exclusively at over-priced, small-plate restaurants, typically serve more than you can eat. In my case, a sandwich was served with a side of coleslaw, which I don’t eat and didn’t see on the menu.

While my micro-experiment was both fun and enlightening, the exercise missed some of the bigger-picture considerations. How can we see beyond the FAO report? Bjorn Lomborg joins the United Nations Food and Agriculture to emphasize the amount of food wasted in the global food system. Lomborg moves beyond the statistic to consider systemic solutions, such as the need for improvements in our global transportation infrastructure. Ronald Bailey’s book The End of Doom points out that we have a highly productive food system that will produce enough food in the future. There’s enough food, it seems, just in the wrong places.

So how do we get all the food to all the right places in the right condition: unspoiled, nutritious and tasty? We could use a focused, concerted effort to address distribution and minimize food left in the field, on the loading dock and in the waste bins of food processors. Those efforts include new packaging, tracking and transport technologies. Everyone, from chefs to consumers, needs a behavior-changing incentive to prepare, serve and consume food in smaller quantities. The move toward selling food in smaller-portioned packages is just a small step in that direction.

These innovations, many of them in the works now, will do much more to lower the amount of food waste than anything revealed in my photos. But, hey, try it yourself. Take your cellphone and snap a few post-meal images of your food trail. What do you see?

by Food+City | Apr 11, 2016 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

Steve Case’s new book, The Third Wave, describes how a “third” wave of Internet innovation will dramatically change innovation in the coming decades.

According to Case, the first wave occurred between 1985 and 1999 when the Internet became almost ubiquitous. During the second wave, beginning in 2000 and ending in 2015, apps appeared, adding ecommerce and Internet entrepreneurs a platform for startups. Now, the rise of the third wave, as Case sees it, is the era of the Internet of Things when the Internet will bring connectivity to solve problems in widely disparate industrial sectors.

If Case is right, entrepreneurs interested in the food industry should look for opportunities to leverage connectivity in ways that will increase food output, optimize logistics, bring transparency, and improve our methods for ensuring the safety of our food supply. Look to developers of agricultural technology for a glimpse of what the third wave will offer: Driverless tractors that are smart and precise enough to better manage water resources, personalize growing in micro-acreage lots, and adjust to all the variables inherent in a changing climate. The cost of technology-driven devices will plummet, big data will make devices smarter, and we will figure out how to solve problems that are not that sexy, but that are fundamentally in need of improvement. Like the elimination of traffic and food recalls. If you think that we’re seeing the disruption of the food supply system now, look again. The crest of the third wave is hard to imagine from where you are today.

Disruption, Case says, will come from unexpected places, not necessarily from the labs at Google or Apple but instead from John Deere, Carghill, Mars, Walmart, and Costco. These companies are investing in innovation, aware that their industry is being disrupted and fearful of not wanting to miss out on the developments occurring in other industries that may or may not appear related to their businesses. Case says, “Corporate executives are too shortsighted to understand how technology that is disrupting a different industry might be adapted to do the same to their own.” Seems like an invitation to the traditional food industry players to look far and wide for new ideas and an enlightened understanding of their customers.

Case can take the view of collaboration too far. He fails to question the government’s increasing reach into our food system. The laws and regulations that limit innovation and creativity within the food system, such as some requirements outlined in the new Food and Safety Modernization Act, need to be reviewed with greater concern for flexibility and affordability for smaller producers and processors. With the coming wave of connectivity between things, government regulations may inhibit connectivity in ways that could keep food costs down and enable healthier food to go to more people. Case feels we should embrace the federal government’s role, accepting its expanding role as inevitable. Government regulation won’t go away, and there are circumstances when it’s a welcome barrier to food fraud. But shouldn’t we proceed with greater caution if we want our new food system to transform in unimaginable ways?

by Food+City | Jul 24, 2015 | Food Tracks Blog, History, Stories

George Huntington Hartford and George Gilman, 19th century entrepreneurs, would flinch at this week’s news that the A & P grocery store chain was filing for bankruptcy. The two Georges created the iconic grocery chain in 1859 and built what we now know as the grocery supermarket. They developed the model for grocery stores that sell low-priced food across the U.S. Now, for the second time in ten years, the beleaguered company has less than 300 stores, down from the 16,000 it operated in 1929. The demise of A & P, the oldest supermarket chain, may be the beginning of the end of the big box, super-sized grocery chains.

Similar to the grocery industry, other economic institutions and industries — banks, taxi services, healthcare, and the hospitality industry — are experiencing “creative disruption.” And food distribution is ripe for repair. The local, personal, and transparent is colliding with accessibility, price, and quality. George Hartford and George Gilman, founders of The Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company, led the first wave of destruction by putting thousands of corner grocery stores out of business at the beginning of the 20th century, and now the effective equivalent of small and local distribution centers may be our future food distribution system.

Marc Levinson’s book, The Great A & P and the Struggle for Small Business in America (2011), tells the story of the rise of big grocery chains from the 1920s until the present day — and how A & P became the world’s largest grocery store chain. Levinson tells us how A & P innovated its way to success only to be come under attack for practices that benefited middle-class consumers by making low cost food accessible. A & P couldn’t find a way to re-create itself amidst pressures from low-priced competitors such as Wal-Mart and high-end stores such as Whole Foods.

By the 1950s the company began a long decline into bankruptcy, unable to resuscitate itself after the onslaught of regulations, attacks, competition, and the loss of its founding team. By building a new aggregated, or “combination store,” as the first supermarkets were called, Hartford and Gilman created often aggressive and innovative ways to bring down the cost of food. Buying directly from food producers instead of wholesales, A & P created some of the first discounted grocery stores. They vertically integrated some activities, such as baking their own bread. They contracted directly with farmers who grew crops specifically for A & P and developed recycling systems for packing materials. The consequence of the new A & P model was the demise of the mom-and-pop grocery store in the early 1920s.

These new approaches to food retailing benefited from the appearance of new technologies that directly improved access to food at lower costs. The first commercial refrigeration systems replaced huge blocks of ice and enabled A & P to hold more inventory. Shoppers could buy enough food for one week without returning for perishable meats and poultry on a daily basis. Open access to food products eliminated the need for a shopkeeper, lowering the store’s operating costs. And when cellophane was developed in France in 1909, the new transparent wrapping material made it possible for consumers to see the food they purchased, a development that increased consumer confidence in food safety.

A & P’s new model encountered feisty competitors and the ire of unions and wholesalers. They fought alongside politicians to push against the growth of the supermarket, joining politicians, journalists and industry associations that accused the brothers of “unfair completion.” The excesses of the Gilded Age and poverty left behind in the wake of the stock market crash in 1929 placed big business in the political crosshairs. Franklin Roosevelt, running on his Progressive ticket, set up regulations, oversight agencies, and rules that threatened the competitive advantages of A & P. Roosevelt called the company a “gigantic blood sucker.”

Accusations of “unfair competition” threaten today’s startups. Taxi cab drivers in both Massachusetts and California are among the many threatened by new economies. Taxi companies have united to sue Uber for “unfair competition.” Ironically, unions are cited by A & P as a significant reason for its bankruptcy filing. A & P officers say that union demands for benefit increases are key to the company’s inability to cut operating costs.

But the accusation of unfair competition raises questions about our current economic landscape. Companies have new competitors, often outside of their traditional industry. Wal-Mart competes with Amazon. And Wal-Mart may be competing with itself. Charles Fishman’s 2006 book, The Wal-Mart Effect (How an Out-of-Town Superstore Became A Global Superpower) suggests that Wal-Mart is so big that their practices are no longer unfairly competitive. Rather, the company is so big that it creates its own market forces. Other big supermarket chains, including Kroger and Costco, both cut their costs to compete with Wal-Mart to offer consumers lower prices.

The tension between Big Box grocery chains and small, independent food retailers continues today, fought with digital weapons and by new players, such as Amazon and Instacart. Signs of the disruption of the grocery industry are apparent across several sectors, from UPS to Google. The re-imagined grocery story is taking shape as a response to the newly food-aware customer who searches for healthy food from a transparent, hopefully human or human-like provider. And the landscape for food distribution may look very different in ten years, populated by Amazon, public food lockers, and encapsulated meals. Amazons’ “buy” button brings customers closer than ever before to a virtual warehouse. And the FAA released regulations for drone tests, the mini-aero service.

Hartford and Gilman’s legacy of supermarkets and low-priced food may continue to be with us but in a new incarnation, more as an aggregated virtual supermarket that utilizes high-tech, “last mile” delivery options. Let’s hope that our future food distribution system will continue to provide better food to more people at low prices. And maybe A & P will re-emerge, making George Hartford and George Gilman proud again.

by Food+City | Jul 17, 2015 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

While “thought leaders” gather around the world to predict the future of food, Italians are hosting this year’s world’s fair, the Milan Expo 2015. The Italians are using the Expo to burnish its brand as the preeminent leader of food innovation. The Italians came up with the Maserati and the Moka pot, so why not edible packaging and digital delivery of food?

But wait, what happened to French leadership in all things food-related? If you attend the Milan Expo, you’ll be hard pressed to see where France fits in. Of course, since Italy is the host of the fair, the affair has an effusive Italian feel. Eataly has a large footprint, as does espresso, gelato, and pasta. And in almost every detail, from the kiosks to the drinking fountains, you can see the fingerprints of Italian designers.

Nations have used these fairs as a platform for nation-branding, so it’s no surprise that Italy emerges as the new leader of food design, taste, and innovation. No telling what the French will need to do to regain their preeminent position as the arbiter of food. Although a group of young chefs in Paris is rallying the new generation of French chefs, they will have to imagine how to regain the crown for leadership of all things food-related now that chefs in other countries have moved ahead without being tied to a stubborn French narcissism. And, in addition to the new generation of French chefs, French entrepreneurs are finding opportunities to regain their high regard for a blend of art and science in food. This summer, 33entrepreneurs, a French startup accelerator in Bordeaux, France, will be traveling throughout the US with its tour of food startup contests in the areas of food, beverages, wine, and travel. (The organization’s use of “33” comes from its goal of “disrupting the way 33% of the world’s GDP.”) Perhaps these young startups will put France back in the game.

After all, the French launched the world’s first industrial exposition in 1798, in Paris, and established France, in particular Paris, as the leader in food and fashion. Everyone, including the English, attended these events, enjoying food created by French chefs and delighting the French flair for fashion. The French expositions were really a display of how technology and art merged to make useful innovations. In 1885, Jules Burlat described the 1844 fair, noting how industrial art and fine art shared the stage. Almost 4,000 exhibitors crowded the pavilions during the 1844 world’s fair in Paris, displaying the latest inventions in industry and agriculture. Steam was the biggest game changer, giving inventors a new source of power. One exhibitor showed how he used steam to power a seawater-to-freshwater conversion system.

These French fairs launched a succession of world’s fairs, including the famous London Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations London Great Exhibition in 1851. The famous French chef Alexis Soyer set up a restaurant in the midst of the British fair, parading preeminent French gastronomy to the six million attendees.

But the Italians have the stage now and the Milan Expo is well worth attending.

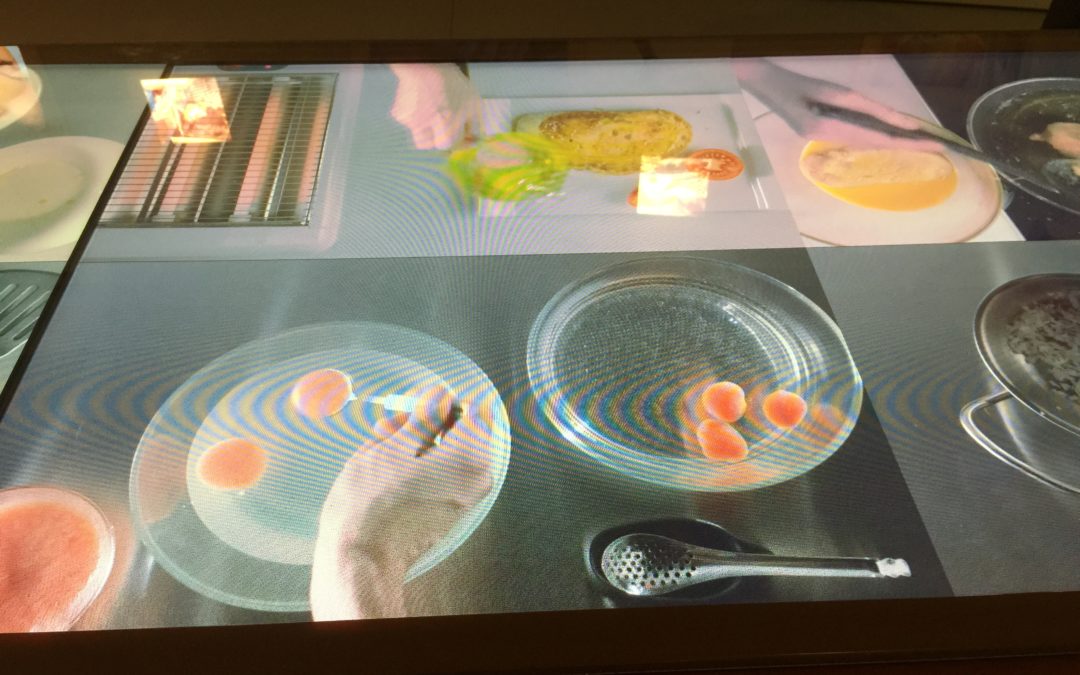

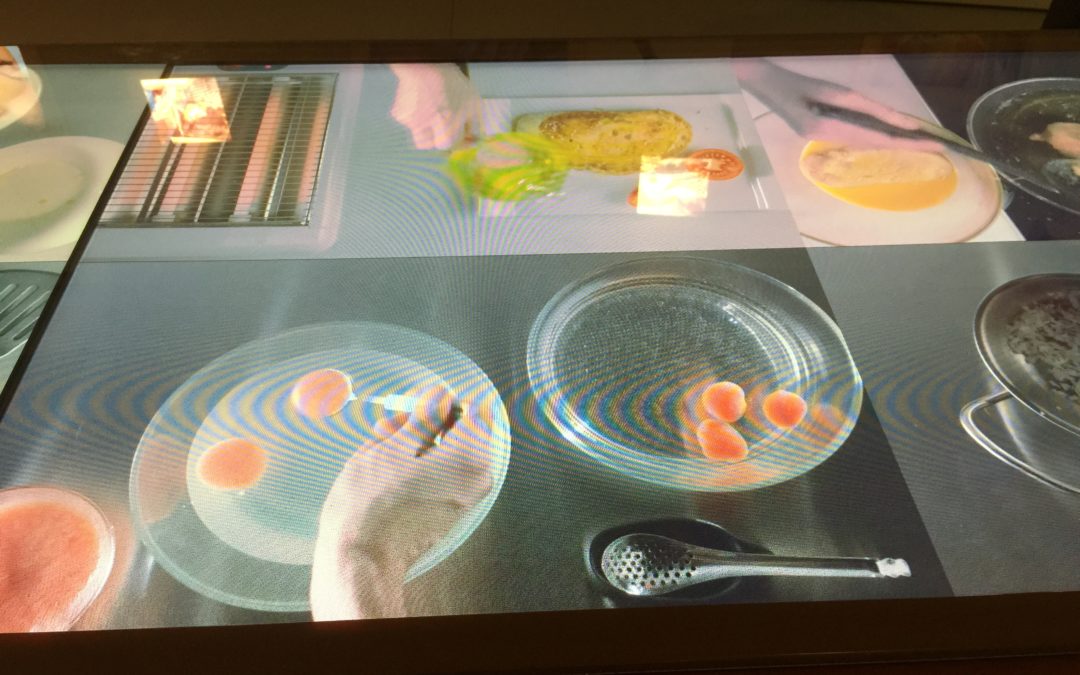

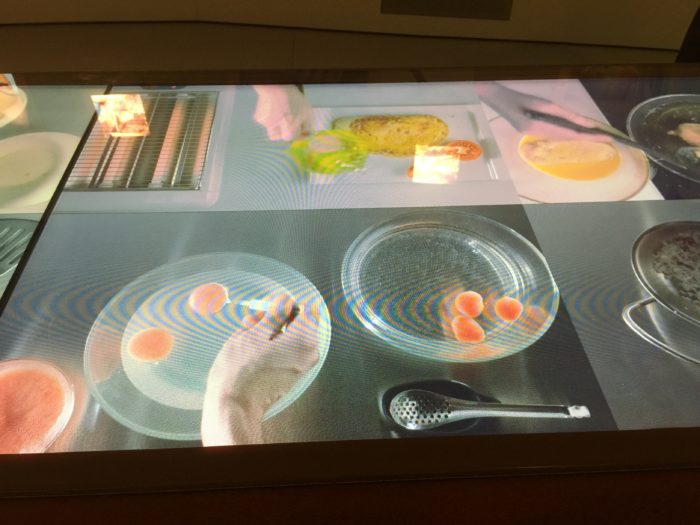

Most of the exhibits are breathtaking. In Europe, where the distances are shorter and the challenges are bite-sized, food innovations are stunning and at the Expo you can see what our food world might look like in 2050. For example, the Coop Market of Italy built a digital supermarket on the fairgrounds. If you want some apples for a snack, you can go to the market, and while you put them into your basket, you can read all about your apples and see who grew them, how they grew them, how the apples traveled to the market, the size of their carbon footprint, their full nutritional analysis, and suggested uses. All this data is stunningly displayed in real-time overhead as you move through the wide aisles. If ever you could imagine how big data might be merged and displayed to create a new transparency of the food system, this moment is telling.

The implications of a convergence of Big Data and Big Food are just beginning to emerge. At the Institute for Food Technologists conference this month futurist Mike Walsh said, “The era of big data will impact not just the production, processing, and distribution of food, but the way that business leaders make decisions.” Seems that your Instagram photos, tweets, healthy metrics, and POS data will shape the our future food system. The data/food mashup will give a digital expression to Anthelme Brillat-Savarin’s infamous statement in 1826, “Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are.”

Other examples of how Big Data will shape an emerging personalized food system is at the McDonald’s exhibit. The new order entry kiosks make the fast food industry minimum wage debate somehow irrelevant. You can watch families crowd around the kiosks while they personalize their hamburgers, adding lettuce and gluten free options as they enter their own orders. A lone McDonald’s staff member stood by a checkout register, the last man standing in the world of mobile payment systems.

A mobile warehouse will deliver your bottle of water that you can sip while watching a mockup of a smart kitchen. The multiple displays and kitchen robots show how your future kitchen may integrate data gathered from your biometric tracking device to design personal food. Your smart kitchen will enable you a comfortable amount of work for you to do with your owns hands with ingredients taken from your pantry inventory that is connected to an online ordering system, connected to the local grocery delivery warehouse. Lots of imagination went into this display. The Expo has a number of displays that take the discussions at the growing number of food-related conferences into the prototyping stage.

The Milan Expo 2015, the international worlds fair with a food theme, brings home the importance of seeing our work in a global context. Innovation outside of the US is alive, fast-moving, and in some ways, ahead of our food innovators. Since countries outside the US, particularly those in Africa and Europe, operate within smaller jurisdictions, they are able to operate without the complexities of multi-state landscapes. That said, the exhibits in Milan are provocative and suggest an integrated, technology-based food system. The Expo was a reminded to think of our work in a global context. Startups and stories need connections to the rest of the world. The next fair, Expo 2017, will be held in Astana, Kazakhstan. Energy is the theme, food served at the fair will be all organic, they say.