by Food+City | Sep 15, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, History, Stories

While the world watches Syria cross red lines, Syrians contend with breadlines. Hardly a grenade passes through rebel or military hands without making an impact upon the country’s food supply. Collateral damage inflicted on crops and animals rarely reaches consumers of news about the Syrian crisis.

Throughout history, governments have recognized the link between war, food, and national security. The Romans noticed the connection when they sought food sources throughout their empire; the French saw a revolution ignite over bread prices, and in 1812 Napoleon observed the starvation of his army in Moscow, leading to his famous remark that “an army marches on its stomach.”

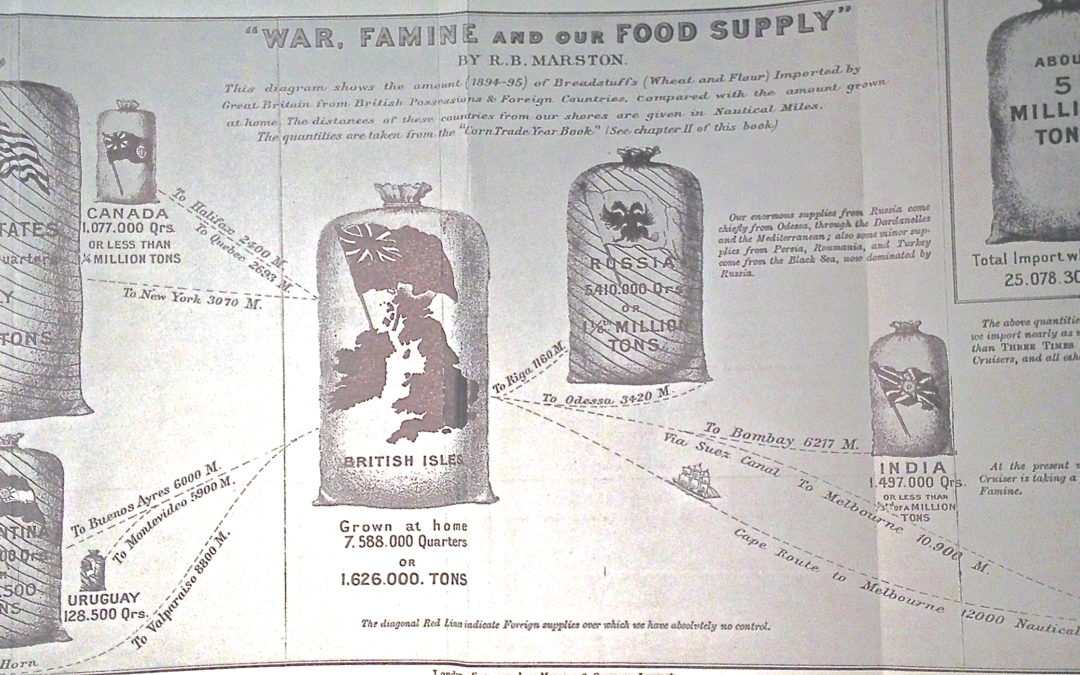

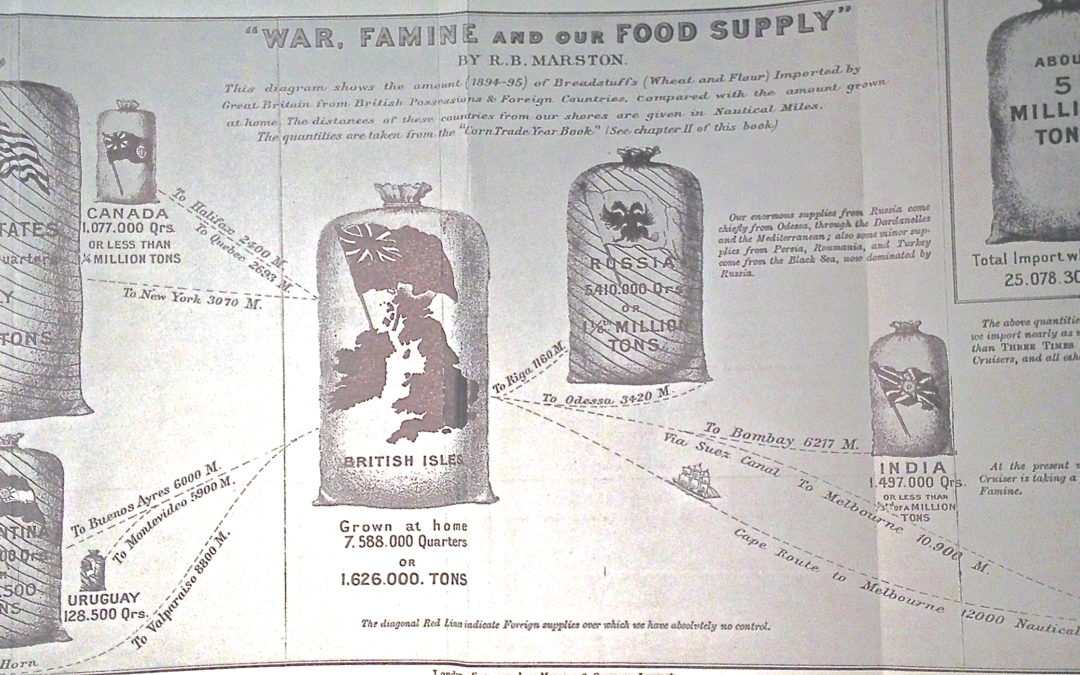

So in 1897, when Robert Bright Marston drew upon Napoleon’s observation to argue for greater food security for Britain, he was well aware of the link between a nation’s ability to feed itself and national security. In particular, he was worried about Britain’s reliance on Russia and the U.S. for wheat and corn. Marston envisioned the construction of grain storage buildings that would enable England to live for three months if a war cut the country off from Russian and American grain. You can see from his illustration how he saw the relationships between grain suppliers and the British grain supplies.

Marston, a British writer known for books about fly fishing, wrote War, Famine, and Our Food Supply to warn Britons that war could disrupt their food supply and somehow bring Britain to its knees. One wonders if urban designers in the early 20th century paid attention to his warnings.

The disruption of Syria’s food supply by civil war has been largely ignored by our media sources but nonetheless grave. While the media talks about casualties from weapons, little is said about deaths caused by famine and poison through the food systems in countries now at war. Few are aware of the destruction of livestock and cropland and the contamination of soil and water over the long duration of some of the modern conflicts.

The ripple effect of unrelenting conflicts is difficult to imagine. The most obvious effect is the breakdown of the infrastructure, especially the transportation of food. In Syria, even the perception of a disruption in the delivery of food causes an increase in black market activity, rising food prices, and higher incidences of hoarding. Pita bread, animal fat, and potatoes quickly disappear into basements and closets. More Syrians freeze and dry food for longer-term storage. As it becomes more and more difficult to transport food to Syria, Syrians look for more localized food sources. Commodities like fuel and flour begin to disappear, creating fears about being able to produce even the simplest but even more essential elements of their diet, flat bread. And, with the potential breakdown of Syrian’s government, comes the loss of state control of bread prices and ingredient supplies.

American cities see the connection between disruptions and urban food supplies mostly caused by natural disasters. New Orleans and New York City are keenly aware of the fragility of food supply chains when a natural disaster such as a hurricane destroys bridges and other food transport networks. In Manhattan, Hurricane Sandy’s impact upon fuel supplies alone immobilized food deliveries.

Cities today are routinely talking about three to five day food supplies, not the luxurious three month supply that Marston was angling for. Whether or not a city needs three days or three months … or three years is a question that needs more attention. Syrians are happy to have three minutes to consume a chemically free meal.

New York wants more than three days of food to keep it afloat in the future. Twelve months would be nice. But who’s to decide and how do we accomplish what Marston argued for in 1897, at least enough food for a country to adapt and find new sources of sustenance?

by Food+City | Sep 8, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

The Blanton Museum in Austin, Texas, is now showing Sam Taylor-Wood’s 2001“Still Life,” a three-minute video of fruit on a plate, rotting. The time-lapse images are transfixing, engaging your senses as you watch fruit decompose, moment by moment. (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BJQYSPFo7hk)

Food and art have enjoyed each other’s company for centuries. Rudolf Arcimboldo’s 16th century painting, “A Feast for the Eyes,” is an classic art/food mashup. (http://media.smithsonianmag.com/images/Arcimboldo-Rudolf-II-631.jpg.)

Food is also fodder for contemporary performance artists and designers. Marti Guimé’s book Food Designing and Marije Vogelzang’s Eat Love portray food in tantalizing, subversive contexts, turning food as material culture into multimedia, multisensory experiences.

At first Taylor-Wood’s plate of pears, grapes, and apples appears static and your eyes search for meaning, observing the stems and small, brown defects of the pears’ skin. And then, as though taking its last breath, the fruit seems to slightly inflate, inhaling one last time before disintegrating, spoiling, rotting, into a final scene where the fruit, consumed by insects, now white, hoary with rot and spumes of gauzy mold becomes a nauseous disgorgement of putrefaction, amoebic shapes insinuating their original form.

How does a video that includes moving images of rotting fruit acquire the title “still life” in the first place? It’s hardly still or a celebration of life. Or is it? “”Still-Life” is part of a Blanton exhibit that describes ordinary objects that are “beguiling, loaded with narrative and metaphor,” which is another way of saying that the works of art aren’t what they seem to be.

A few years ago I visited the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in Boston. The museum had just moved into an audacious building at the edge of the waterfront and was drawing crowds eager to see new exhibits.

One room included an example of “performance art,” a pile of clothing pushed into a corner. Seemed like the emperor indeed had no clothes, at least at the ICA. By the time I returned home from the exhibit I felt compelled to react to what seemed at the time a display of an artist’s complete lack of creativity. But, for a week, I tossed down my clothes each night and took a photograph. By the third night, I was rearranging the clothing, observing where colors and textures overlapped or where the composition seemed out of balance, overwhelmed by a pant leg or disconnected from an orphaned sock.

The surprise came at the end of the week when I posted the gallery of photos here:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/90414796@N05/sets/72157635382777662/

Aha, I had become the perfect participant in the performance of art at the ICA, provoked to react, pushed to think more about the meaning of art. The pile of clothes wasn’t just a pile of clothes. The exhibit beguiled me, like the rotting fruit, just as the fresh apple beguiled Eve, into believing that clothing had other stories to tell.

Seems the convergence of art, science, and food is underway. Meanwhile, I can never look at a pile of clothes or a plate of fruit in the same way, can you?

by Food+City | Aug 29, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

In today’s noisy, scrappy conversation about food, a pitch-perfect note once in a while bubbles to the top. Bee Wilson, a food historian and author, recently brought us one of those sparkling notes in her review of William Sitwell’s new book, A History of Food in 100 Recipes. Wilson writes reviews in The New Yorker and sometimes her own books, such as Consider The Fork, published by Basic Books in 2012.

While offering her thoughts on Sitwell’s attempt to extract historical narratives from ancient recipes, Wilson slips in a short riff about storytelling and the idea that a recipe is a story. As a fictional story, a recipe hints at the possibility of a resolution. A recipe invites a reader to follow a narrative, a set of instructions, with ingredients that have their own character traits along a story arc that evokes both drama and denouement. The setting of the story belies the writer’s own attitude, place, and culture. Recipes can be stories within stories.

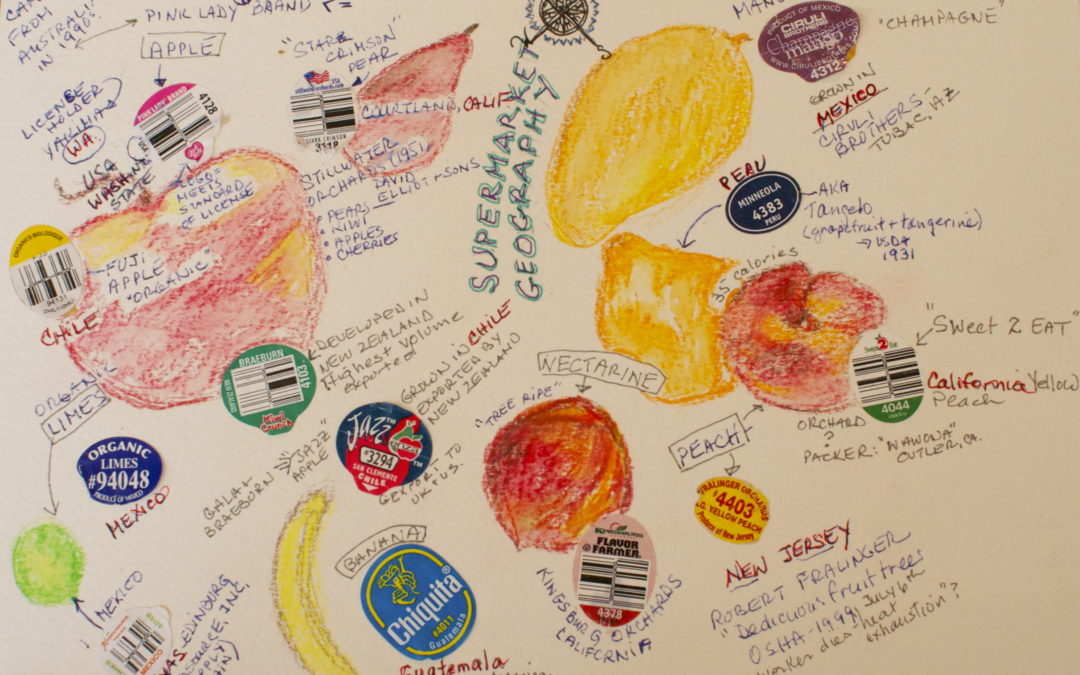

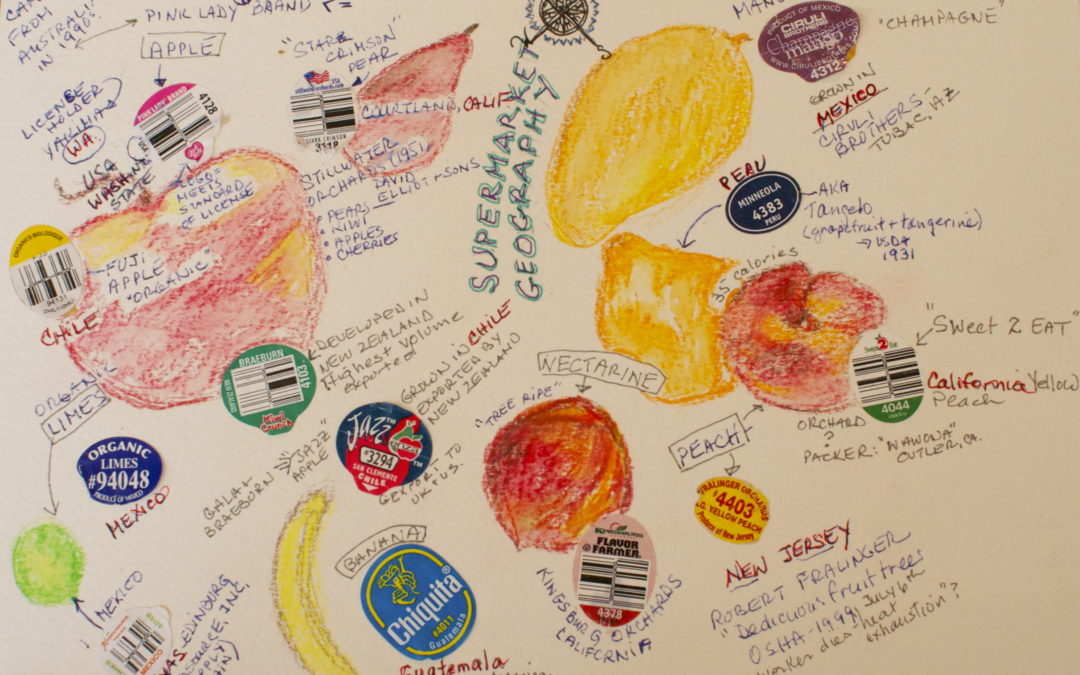

But so can other readable texts, such as those pesky stickers that adhere to the fruit we buy from grocery stores. For a week this summer, I began peeling off PLU stickers from the fruit that I purchased from two grocery stores. PLU stands for “Price-Look Up” and are codes that tell us where our fruit comes from and how it was produced. The codes first appeared in 1990 and are now sometimes accompanied with bar codes. They lubricate the trade of produce around the world.

The codes are easy to decipher: Four digits indicate the probable use of pesticides, five digits beginning with a eight mean that genetically modified organisms were used during production, and five digits beginning with an nine mean that the fruit was produced using organic methods.

I randomly chose the fruit, not intending to buy local or organic or non-organic, but buying what I needed at the time and looked fresh. The stories of these fruits emerged and included the following: None of the fruits were genetically modified. Out of twelve fruits, only two were organically produced, which was surprising since at least half of the fruit came from a Whole Foods Market in Maine. The rest were non-organic and came from California, Mexico, Guatemala, New Jersey, New Zealand, Chile, Washington state, and Peru. Here is my PLU Map.

By looking up the codes, you can sometimes find the names of the growers, packers, family names and histories. Some of the stories that surfaced were personal. One grower had received an OSHA violation for a worker who died of heatstroke while harvesting fruit. Reading the details of the worker’s death, I felt uncomfortable, sensing that these details were not for public consumption. I wonder how this individual’s family would react to the knowledge that someone who casually bit into a nectarine shared the intimate details of his demise. I was left wondering if the grower was somehow responsible for the death, or was the worker already in poor health and in spite of being advised not to come to work, came anyway on one of the hottest days that year in California.

So even PLU stickers reveal stories, like recipes, complete with drama, tension, and resolution. Someday those stickers will be edible and we’ll eat the words of producers, food scientists, and processors.

Stickers, recipes and Bee Wilson’s fine story telling are contributing to my current interest in storytelling. How many ways can you tell a story? What makes a good story? What do you think?

by Food+City | Jun 25, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

Yes, just spent a week logging miles upward and downward. After a week in Paris, I joined my family for a week-long adventure in Bohemia, in Grainau, where the alps gather around the border between Germany and Austria. Three of us competed in the Zugspitz Ultratrail Race set in the shadow of the tallest alp in Germany. I ran 25 miles and my two children each ran 42. But the kicker was the 9,000 feet up and 9,000 down for the kids and 6,000 feet up/down for my distance. In the rain, and fog, and over rocky, slippery trails. I finished in 7 hours 21 minutes, Julia in 12 hours, 10 minutes and Max in 10 hours 49 minutes. A long day, but exhilarating in every sense, wet, rough, fragrant pine trees, and icy snow. It was one of our toughest trail races, mostly due to the wet, steep conditions. The event, known as a mountain trail run, was all about the elevation, not so much the distance. But the mountain came with new friends, stories, and a sense of awe at the group of 1,000 runners that shared the event with us. Most were German, but because of the proximity of the Marshall Center for Security Studies in Garmish Partenkirchen, Americans competed supported by their families waving American flags along the finish line. For our compatriots and the local German runners, the race brought us into sky-piercing mountains, fields of wildflowers, tinkling cowbells, and alpine streams, not to mention crusty, salty pretzels and endless amounts of hot, juicy German sausage. All good, now onward.

by Food+City | Jun 17, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

June 13th – Day One

Am setting off to track the ingredients of food items made in cities around the world. The purpose is to better understand how cities are fed, mapping out the movements of ingredients from the origin of raw materials to the plate of the consumer. So, starting in Paris, with a simple ham and cheese baguette.

Slept all the way through the 10+hour flight to Munich and then on to Paris, arriving during a one-day taxi strike on a rainy day. Am staying in a small hotel, Hotel Verneuil, located on a quiet street on the Left Bank St. Germain des Pré district. After a quick shower, a strong espresso from the cozy, wood-paneled lobby, I headed off to meet Lauren Shields, my researcher who has been soldiering on through her list of contacts to set up appointments for me during my visit.

Lauren is an American, born in Montana, studying international food policy at a French university. She graduated a few weeks ago and is now on the hunt for a job somewhere in the European food policy universe. She met me for tea at the Comptoir des Pères, where we talked about our plans for the next few days as I sipped a tisane and she a “noisette,” an espresso with a small pitcher of hot milk on the side. We talked for two hours, and developed a list of ideas, places to visit, and some questions. Such as, “Why don’t Parisians talk about locally food? Perhaps it’s because they think of all of France as their backyard, and thus all food produced in France as local.

June 14th – Market Day

Tumbled out of the hotel at 4:30am for a tour of Rungis Market, one of the largest wholesale food markets in the world located southwest of Paris. As the sun rose, we entered the Fish Hall, lights glaring, floor shimmering wet, and white Styrofoam boxes for the length of the icy-cool space. A display market, meaning that buyers and sellers see the fish, touch the merchandise, and settle on prices rather than purchase catches through an online auction system such as buyers in Boston. During the 1960s, Rungis replaced the famous and historic Les Halles market in central Paris, the site of Emile Zola’s novel The Belly of Paris.

The only way to officially see the market is to join tour or be a buyer. I joined a tour and was stunned (difficult at 4:30am) to find a large tour bus packed with tourists from all over the world who rallied early and paid to see a wholesale food market. Would anyone in New York get up at 5am and get in a tour bus to visit Hunters Point? Doubt it, but that might change.

We spent five hours walking through buildings that contained fish, beef, chickens, offal, vegetables, fruit, cheese, and more, much of which was contained in 40-degree Fahrenheit temperatures. The market is so big that the tour buses drive from one building to another, winding through trucks and forklifts that are trying to get business done before the market closes. And our group, like all the other touring groups, wandered wearing the required hairnet and white coats, making us look like clueless inspectors, pointing and asking questions that the vendors had answered at least a dozen times that morning.

The professionals in the market did not seemed annoyed with us, as we blocked traffic, got in the way of carts moving produce out onto waiting delivery trucks, and pointed cameras into the boxes of fish, meat, and chickens. The star attractions included the chickens with their heads looped around their carcasses, large bloodied beef hanging along with a photo of the animals when they were alive, tranquilly grazing in their home pasture, cases of foie gras, and piles of detached pigs feet, stomachs, and calves brains. Pretty tough going for a pre-breakfast visit.

In spite of all the fresh and glory food, the halls were amazingly clean, stainless steel gleaming, and floors immaculate with the exception of a few drops of blood left by those animals hanging unsold by the end of the market day.

More details of the market will be forthcoming, but to give you a flavor of the morning visit, here are some samples of what awaits you should you decide to become a wholesale market tourist in Paris.

June 15th – Say Cheese

Sounds simple, yet Parisians just can’t tell us what kind of cheese they use to make their traditional “jambon/fromage,” or baguette with ham and cheese sandwich. I’ve been asking Parisians now for almost a week and each person declares with absolute conviction that the cheese is Emmanthal. No, actually, it’s Gruyere. Oh, wait. It’s Comte cheese.

The ham is another story, but one that exacts almost a sense of apathy, which for a Parisian seems out of character. The ham used for the sandwich is sometimes call Jambon de Paris, or Parisian ham, but is really just a simple boiled ham, not tied to any location or terrior, which in other cases is the Parisian claim to culinary authenticity.

Same for the bread. The baguette has no geographical identity, other than all of France, and comes in various combinations of flours. The only exactitude required is the government regulation for the combination of ingredients: flour, water, salt. The French state has had its hands in bread at least since Louis XV (1710-1774).

The temperamental French view of the cheese in their iconic sandwich led me down some blind alleys. Such as one at the end of a trip to the Jura, Comte region south of Paris to investigate the source of Comte cheese. The tour guide of the Comte cheese center proclaimed the excellence the forty-pound rounds of gruyere-like cheese, including the astounding fact that only one breed of dairy cow is allowed to make the cheese, the Montbéliarde. The cheese, while creamy and, depending upon its age, nutty, turns out not to be the cheese of choice for the “jambon/fromage.”

Two days later, the consensus is that it is Emmental, a Swiss cheese, is the traditional cheese eaten by most Parisians in this sandwich. For now, am running with the holy cheese, finding what French company is making the Swiss cheese for the French sandwich.

June 17th

The Sandwich: Jambon/Fromage

Tracking down a sandwich is my mission, this one in Paris, and made by the Martin family in the 10th arrondissement. By tracking down the ingredients for one sandwich, made by one shop, makes the task of understanding how Paris gets fed manageable, although still confusing and complicated. Ingredients for one food item at one location often change from one day to another; bakers buy their yeast from the best supplier at the most reasonable cost, for example.

The vagaries of supply chain dynamics means that you can’t track down all ingredients for all sandwiches made by one baker, but simply one made at one time on one day. Thus the challenge. And the opportunity.

So the tracking began today and thankfully, our bakers were all in, happy to share their shop, ovens, and interest in the adventure. They hauled out flour sacks, tubs of salt and yeast, and labels from packaged ham and cheese. Yes, Emmental. Next step: find those supply chain delivery trucks, the ham processor, cheesemaker, and yes, the cows and pigs.

by Food+City | Jun 8, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

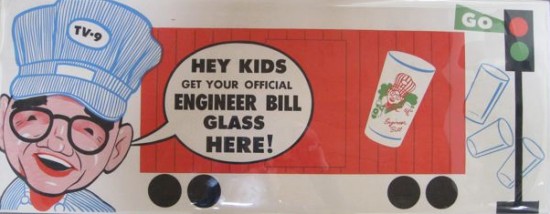

My last post about the early years of food on TV brought back memories of those days of easy pleasures created by the mere presence of a TV in your home. In our house, the small black and white television sat near the kitchen and after school we gathered round to watch Engineer Bill drink milk in between cartoons that he ran with his program, Cartoon Express.

William Stulla, AKA, Engineer Bill, began his program in 1954 and rolled into living rooms at 6:30 in Southern California, when I was six years old. Our family wouldn’t miss a night.

For a few minutes every evening, around the dinner hour, he would appear in his railroad engineer garb clutching a glass of milk and challenge us to gather around the TV with our own full glasses of milk. He would announce the start of his game, Red Light, Green Light, a game that entailed drinking milk whenever “Freight Train” (his off-set announcer producer) shouted “green light.” Every few seconds he’d shout Red Light or Green Pants or some other feinting ploy to fool us into drinking at the wrong time.

Families like ours were gathered around our small sets, giggling and gulping all the while in an effort to finish our glasses of milk before we mistakenly drank at the wrong time. This required us to be riveted to the TV. Engineer Bill played with us and for those of us who succeeded in downing all of our milk, he’d ring a bright bell and for those of us who stood grasping a glass still full of milk, he rang the “lead bell.”

This was a time of cleaning one’s plate, drinking your milk, “building bodies 12 ways”, as the bag of Wonder Bread claimed.

The game was fun and apparently we must of gulped down gallons of milk over the years of our early childhood, me and my two brothers.

But wait, what if we replicated this program today, gathering around the TV, clutching bags of freshly picked green kale or a probiotic yogurt smoothie. Would the tactic work? Would this be our modern gamification of good eating habits? Could we engineer a new generation of vegetarians or even vegans? Or, would our children see through the thin veneer of good intentions? Would adults accuse the milk lobby of victimizing our children? Or would the competitive nature of the game put off those who are revolted by the ideas of winners and losers?

Still, maybe an opportunity to find a motivator for our younger generation to develop good eating habits. (Although gulping might not work.) Instead of wishing our children to eat kale because it’s “sustainable” and good for our planet, perhaps we could fast track their healthy diets by a new engineer, one that builds software, and introduce a game that counts towards building a generation of healthy kids.

Skip to minute seven in this video to catch a clip of the Red Light, Green Light game. https://youtu.be/GzvdlE45XEI