by Food+City | Jun 18, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

Austin is bursting with enthusiasm for food. Even better, our city fosters innovative startups that add to the richness and experience of the food scene.

Foodies, food trucks, and fans of food in general have thrived and grown over the last twenty years, driven by the mix of musicians, college students, and artists seeking cheap and delicious food. Thus the food truck phenomena hit Austin first, giving our city a reputation for being a scrappy player in the food scene.

The recent surge of interest in startups and entrepreneurship has encountered the food movement here, creating the ideal climate for food-related incubators fostering the birth of new food companies. One new innovator entering the market is Molly Lindner with her company, Choxolat.

Lindner’s description of the creation of Choxolat offers a glimpse into how her process might provide a model to other innovators who seek access to Austin’s unique and vibrant food culture. Her process includes methodical due diligence, careful gathering and curating of knowledge from experienced mentors, and experimentation with new ideas. Successful entrepreneurs build their companies by paying attention to this process, gathering first-hand knowledge that offers entrepreneurs entry into the business world in ways that give their startups a fighting chance to survive and thrive.

But what is noticeable and a bit unsettling is the number of young startup teams that want instant access to a food scene that is complicated and still emerging here. What these new teams lack is a sense of the importance of process.

While living in Mexico City and working for USAID, she became interested in the coffee business. With connections in Austin, she took a few research trips to explore the local coffee scene. She noticed that Austin’s baristas were doing just fine without her, a potentially disappointing discovery. Except she also observed that these coffee geeks infuse their chocolate flavored drinks with unexceptional syrups. This paradox inspired a different business concept: Lindner’s Choxolat would provide baristas with an equally exceptional and consistent drinking chocolate, called Sip, to match the quality of their coffee.

The process continued and included trips to the San Francisco Fancy Food Show where she found a food business coach. With a coach knowledgeable about launching a food business in tow, Lindner then assembled the rest of her “A” team of specialists: a chocolatier and a public relations and marketing company. These three individuals brought skills that compliment Lindner’s persistent discovery and education.

Why do many startups fail? They fail because they are in a hurry. Many new entrepreneurs are in a rush and forget the importance of not only meeting those in the food scene but of listening to them. Because many entrepreneurs are impatient, they are often motivated more by “running a company” than finding an opportunity for solving a problem. They often startup a business that is long on enthusiasm and short on knowledge.

A blend of three high-end chocolates finely ground into a powder quickly combines with milk to produce a rich dark chocolate drink that combines well with coffee or thrives on its own. Her powdered blend of Belgian chocolate is 60% cocoa with the addition of sugar and Himalayan pink sea salt, her signature Sip drink that is called Dark with Sea Salt.

Lindner and her family are moving to Austin as her drinking chocolate is hitting the stores. She is actually selling more to the local retail market, which has discovered that her blended, powdered drinking chocolate stands on its own. Spicy Spice, Peppermint, and Dark Cherry are some of the other flavors in her line of chocolate powders. And just for fun, her customers, baristas and chocolate-sippers alike, sell her marshmallows, which she describes as like “clouds on a sunny day.” Sip’s chocolate beverages are available at Austin’s farmers’ markets and Austin retail stores such as Whip In and Thom’s Market.

Sip is a product of Choxolat Concepts, Lindner’s company in Austin. Following in the tradition of 17th century European coffee houses, baristas in Austin will now be able to provide their customers with fine chocolate along with their artisanal coffee beans.

by Food+City | May 16, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

Back on their feet after weeks of having their reputation besmirched by tales of pink slime, cattle are drawing attention to the complexities and uncertainties of our food system. Chinese dairies, mad cows, and powdered milk illustrate how the milk and meat industry adapts, pivots, and innovates in a dynamic and rapidly changing global market.

While remotely connected, the occurrence of one mad cow in Tulare, California, powdered milk producers in the US and 25 shiploads of cattle moving from South America to China all point to an intricately connected food system. The production of meat and milk is linked not only to the emotions and ethics of consumers but also to food security crises and global restructuring of supply chains.

Consider the recent finding in California of a cow with mad cow disease (BSE, Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy). A consequence of eating meat from cattle fed animal byproducts, the disease causes brain degeneration in humans. BSE first appeared in North American in 1989. Since then, hundreds of thousands of cases have been detected and animals destroyed both in the US and UK. This recent case only puts cattle and consumers on tenterhooks, awaiting news about further outbreaks. Found on a farm in Tulare County, the cow raised concerns about the possibility that entire herds may be tainted, threatening human health. While the USDA continues its investigations, producers and consumers are left hanging about the impact of this incident. Having just recovered from the pink slime media hysteria, when the meat industry had to retool and pivot around concerns over meat processing, producers worried that this one cow will disrupt their business again.

While this fear lingers, China is concerned about scaling up its own dairy producing industry. More and more Chinese are drinking milk and enjoying ice cream, increasing China’s need for productive dairy herds. Seeing this as an opportunity, farmers outside of China are shipping cattle to China. According to The Wall Street Journal, 100,000 heifers arrived this year from New Zealand, Argentina, and Uruguay in response to a drive to produce a new generation of productive dairy cows in China. Chinese cows don’t produce much milk compared to cows in other countries. Lacking the spirit of innovation inspired by capitalism, Chinese farmers have cows that annually produce four tons of milk compared to nine in the U.S. Imparting years of experimentation and improvement of breeding knowledge, American farmers and others outside China, are sending their intellectual property (cattle) to China, seeing the short term advantage of new markets. In the long term, American farmers should consider the effects of exporting their best breeding stock.

American farmers are responding to this new demand by exporting cows, investing in the modernization of Chinese dairies and developing new products. Chinese producers are turning to the U.S. model of industrial dairy farming and are accepting financial support from such preeminent U.S. investment firms as Kohlberg, Kravis and Roberts.

In addition to shipping cattle to China, American milk producers have found another opportunity in China. U.S. powdered milk producers are retooling in order to satisfy a growing demand in China for milk. With rising incomes and a move towards Western food, the thirsty Chinese cannot quench their desires with Chinese milk and so purchase large amounts of powdered milk. U.S. farmers are changing their own production process in order to make powdered milk with a long shelf life, a requirement for Chinese milk consumers. Since many Chinese families lack refrigerators, the long shelf life is critical. Dairy companies such as California Dairies, a cooperative in Central California, have taken notice and have invested in new technology in order to produce this longer-lasting dry milk.

What these stories tell us is that American farmers are adapting and innovating to constant change and crises in the global food system. And these adaptations surfaced during just one week. One week since these news stories, U.S. cattle futures were already beginning to rebound, responding to the upcoming grilling season and low inventories due to herd reductions from lack year’s drought.

Imagine these adjustments and innovations for hundreds of thousands other subsystems and supply chains within the global food system. How can we connect all the cultural, economic, political and environmental changes that affect our food supply? I suggest we begin by digging deeper into our understanding of the system. Let’s explore those connections during the upcoming months. Want to join me? Add your ideas for who ought to be considered part of our global food system. Farmers, yes. That’s obvious. But what about the producers of ice? Or cookie sheet manufacturers? How far are you willing to go?

by Food+City | May 14, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

You don’t have to listen to Jim and Mike Richardson talk about their farm for very long before you know they are improvers. Their farm is a laboratory for experimentation with forage varieties, poultry houses, pig feeders, and grass-fed beef. Building upon the experience of Jim’s long career as a veterinarian and Mike’s enthusiasm and curiosity about farming, the two of them are well equipped to improve food production in Central Texas.

The Richardson’s innovations join a long tradition of agricultural innovators. During the 18th century, British farmers were also improvers, experimenting with what has been called “scientific agriculture.” The raising of crops and animals drew upon the principles of the Enlightenment, rationalizing what was once only left in the hands of nature, the weather, the whim of the animals left outside to breed. Farmers like Jethro Tull came up with the seed drill; Robert Bakewell came up with a systematic way of breeding livestock. Agriculture moved away from common pastures that were dependent upon human labor to highly productive, enclosed pastures, feeding a rapidly growing British Empire by the 19th century. These new “scientific” farmers were innovators, creating new ways of looking at old knowledge.

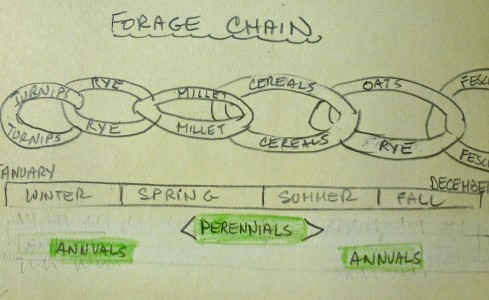

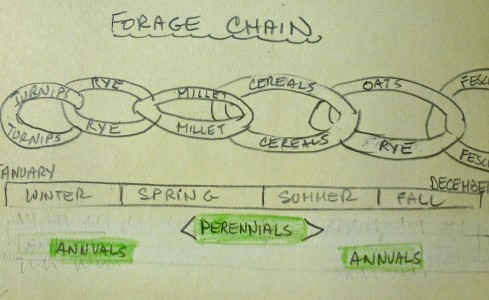

Improvement requires innovation. The Richardsons, 21st century improvers, bring grassfed/finished beef, pastured pork, and poultry to farmers markets and local grocery stores. Captivated by the possibilities of improving the forage chain and exploring ways of growing crops in a drought, they want to balance the use of technology with their desire to remain connected to the land and their customers. (A forage chain is a sequence of grasses and other forage that become ready to use at different times of the year, providing a steady supply of feed for livestock.)

The animals on their pastures are benefiting from the Richardson’s penchant for improvement. Their poultry lives in movable chicken houses, which are frequently moved in order to manage forage and provide grass to the ducks, chickens, and turkeys. Jim and Mike are learning about grading of eggs so that they can improve their farming practices. Instead of moving poultry houses by hand, they use the latest model John Deere farm equipment. And they are well-versed with social media. By talking to other farmers, agronomists, and university extension services, these two improvers are listening for ideas that they could use to make their farm more productive, enhance the quality of their animals and crops while addressing the requirements of the soil and climate of Central Texas.

Mike is intensely aware of the challenge they face with diminishing water supplies and increasing demand from their loyal customers. While he wants to use progressive ideas to improve his farm, he is alert to the potential for moving ahead while leaving his customers behind. The Richardson family thrives on their relationships with customers. They aren’t willing, it seems, to make any changes that would risk these relationships. Balancing the social and financial sides of farming certainly complicates life for these modern day improvers. But they aren’t the first improvers to feel this tension.

Joyce Chaplin, a history professor at Harvard University, wrote about Southern farmers in 18th century who were uncertain about modernizing their practices while at the same time enthusiastic about innovating and adapting to new, more scientific agricultural practices.

One of the reasons, as Chaplin points out, that the Southern farmers were uneasy about modernizing was that while they were moving towards more modern ideas and practices they were enmeshed with traditions, like slavery, for example. In some ways, they were somewhat selective about moving abandoning old ideas. Perhaps those farmers were worried that by moving too fast, rejecting the idea of slavery with too much abandon, they might be responsible for the unraveling of the fabric of southern society. So, they moved away from farming tobacco and began growing cotton, finding a crop that would grow in the depleted soils left behind from years of tobacco farming.

While it may seem like a stretch, to compare a slavery dependent 18th century farmer to a modern day family farmers like Richardson Farms, you can sense the same tension between farmers who want to improve in a complicated world. Those Southern farmers innovated with new crops even though they were slow to reject slave labor. The Richardsons are innovating with new forage systems while reluctant to use traditional practices such as grain-finishing cattle or drilling soil for seed planting.

The reluctance of these improvers might be a good sign, indicating thoughtful innovation that integrates social values, a slight handbrake to the rush to be new.

(For more about those Southern farmers, see Joyce Chaplin’s book An Anxious Pursuit: Agricultural Innovation and Modernity in the Lower South, 1730-1815, University of North Carolina Press.)

by Food+City | May 2, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

Lew Weil, a molecular biologist, grows seaweed for his company, Austin Sea Veggies. In his garage, Lew grows ogo, edible seaweed that looks a little like material for a gelatinous bird’s nest. Where else but Austin, Texas, hundreds of miles away from any coastline, would you find a scientist hunched over an aquarium full of seaweed. Yes, Austin is weird.

But beware of weird. More often than not, an Austinian’s weirdness leads to innovation and an audacious capacity for leapfrogging the rest of us. Lew began his metamorphosis from lab scientist to aquaculturalist when he wondered if there was a more sustainable way to grow agar, the substrate used in Petri dishes for growing microorganisms. Agar comes from polysaccharides in red algae; Japanese and South Asian companies grow most of the algae in farms along their coastlines. Lew thought there might be a way to grow algae and seaweed without relying on coastlines. Since seaweed enters our food chain more often than you may think, like through ice cream and carrageenan-toting apple cider (even your toothpaste has it), Lew foresaw the time when the need for seaweed would outstrip the supply of coastlines. Maybe Lew isn’t that weird.

In 2003, the Food and Agriculture Organization reported that the annual value of seaweed produced for human consumption in the U.S. was $5 billion.[1] But the largest producers are in China and South Asia. After testing and retesting types of seaweed, Lew embraced ogo, from Hawaii and popular with Hawaiians, he moved beyond agar to producing seaweed for human consumption. Enter Austin Sea Veggies. Growing edible seaweed became an obsession for a mad microbiologist. With a degree in biology from Texas A & M, Lew approaches his quest for sustainable seaweed aquaculture using scientific methods with all the geekiness of an agar-ian scientist, now an agrarian scientist.

Lew’s experiments seek an understanding of the seaweed’s growing seasons, its ability to endure temperature oscillations, like the furnace-blast heat during a summer in Texas. Last summer he lost his entire crop and is just now beginning to recover with a new set of “mother” plants. His ogo grows from these plants, its delicate, lacy fronds emerging from the tips of the mother branches. His customers, many of them members of the Hawaiian community in Texas, are anxiously awaiting fresh deliveries of his new crop, typically five to six pounds per month. Restaurants and grocery stores such as Wheatsville, snatch up his “sea veggies” on a regular basis.

But scaling is the entrepreneurs’ vexation. Success brings customer demand, and in Lew’s case, an aquarium in his garage won’t begin to produce enough ogo to satisfy his hungry customers. So look has been talking with other entrepreneurs, including one who has a saltwater quarry in West Texas, an auspicious discovery when oil drillers penetrated the Permian Sea basin, which exists throughout much of the Texas landscape. Salt water gushed into a quarry and sits underutilized for aquaculture, but not lost on Lew. He has a vision for using the saltwater quarry for growing seaweed and shrimp. All he needs is the cooperation of the quarry’s owner, some capital, and a little time off from his day job as a biologist. The scaling bugaboo is the barrier that many food entrepreneurs encounter, some successfully, others not. To get Lew’s food science out of his lab and into sustainable production will take the graces of another entrepreneur, one that turn the Permian Sea into an ogo incubator.

How enterprises like seaweed companies in Austin fit into the global food system, or even more miraculously, into Austin’s food system? As a food entrepreneur, Lew easily fits into Austin’s vibrant food culture. But what about seaweed? And seaweed grown in garages? Steve Jobs began in a garage.

by Food+City | Apr 25, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

“No cakey-ass brownies here,” declares Miles Compton about his baked chocolate dessert. In a food culture that insists on knowing the farmer who grows its corn and the exact percentage of butterfat in a cookie, how is it that Miles is so successful with his somehow unknowable chocolate dessert?

Long-time Austin food columnist, the late Katie Crider said that Mile’s dessert is “anything you want it to be.” And she was right. Virginia Wood, another Austin food writer said the dessert was “a cross between a brownie and a melt-in-your-mouth chocolate truffle. And she was also right. Unable to endure the suspense, I followed Miles’ directions, ate his chocolate dessert cold, and found it almost fudgy, full of intense quality dark chocolate, and was surprised that the top crust could retain such a light, crisp texture. I was beginning to see why his customers come back for seconds.

For sale in Whole Foods or Central Market in Texas, his chocolate dessert looks like a brownie. But it’s not. But it’s also not a gooey fudge-like cake. Sitting in its clear plastic store container, Miles’ dessert begs for answers. Why does this mysterious dessert have such a loyal following in a food culture that expects to know the ingredients of everything else?

Miles is good at creating the mystique that follows his desserts to the table. No amount of subterfuge will divulge the source of his chocolate or his recipe. His website flaunts his main ingredients, butter, eggs, chocolate. But that’s all. Nothing about local eggs, exotic Valharona chocolate, or hand-made butter. His customers apparently give him a pass, consuming hundreds of pounds of Miles of Chocolate, as it’s called, over the past decades.

Miles of Chocolate, made by Miles, an ex-Marine, has what marketers call “stickiness.” Not to be confused with how his chocolate creation can feel in your hands, the stickiness of his dessert is more about how his customers remain loyal as culinary trends change and warning from health officials about the detrimental effects of eating butter. In his book, The Tipping Point, Malcom Gladwell points out that some products will survive because of a particular quality. Miles has found the sweet spot that causes his customers to remain stuck on his desserts, in spite of his mysterious recipe and unimaginative packaging.

These nine-by-thirteen rectangles of chocolateness could be mistaken for large brownies. Brownies, so called because of their color (originally from molasses in the early recipes), made their appearance in the 1897 publication of the Sears Roebuck Catalog but were also consumed at the 1893 Columbian Exhibition in Chicago. Somehow, Miles has transformed this enduring confection into “crack disguised as the best brownie you’ve ever had,” as one Yelp review exclaimed.

Two people run Miles of Chocolate, Miles and his business partner Ben, both in business for about eight years. Over two decades ago, Miles’ hairdresser/astrologist consulted the stars and announced that Miles should be a chef. Beginning as a dishwasher, Miles began baking after several years as a chef, working in Corpus Christi and then Austin. He soon discovered and tweaked his chocolate dessert recipe, now the star attraction of his business. Five stars glow from his logo, a self-assured declaration familiar to restaurant reviewers.

Not content to rest on his laurels as a recipient of the Austin Chronicle’s award for the best local chocolate for four years running, Miles fits into Austin’s food scene by displaying a familiar creative resistance and nonconformity the local culture. By refusing to admit his dessert is a brownie and concocting it with unimaginable amounts of eggs and butter, he plays to Austin’s creative audacity, the same audacity that evoked the “cakey-ass” comment. And there’s plenty of evidence that he knows what he’s doing: his customers eat up his culinary attitude, coming back year after year. Thank the stars for Miles of Chocolate.

by Food+City | Apr 17, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

While pondering the nature of our food system, I find parts of it in places that seem unrelated, at first. A bakery in Austin may seem connected to the system through the production of bread, the loaves and croissants traveling from the baker’s commercial kitchen into the hands and mouths of hungry Austinians every morning. But the system engages other less apparent components of the system, like dairy companies, flour manufacturers, and truck drivers. A recent visit to the bakery shed light on how these other companies contribute to the crusty loaves from one small bakeshop.

Derek Stilson, owner of Moonlight Bakery in Austin, Texas has been observing the moonlight for decades. A graduate from the University of Texas in Linguistics, he picked Moonlight for the name of his bakery with an eye towards descriptive meanings of words, connecting the moon, light, moonrise, and bread rising. Derek comes to bread through years of training, first as Whole Foods first in-house baker, then through stints at local Austin restaurants and bakeries before attending the American Institute of Baking in Kansas and teaching culinary arts at an Austin high school for eight years. Since 2003, he and his wife, Norma, owned the Moonlight Bakery, a small bakery that produces classic breads and pastries.

While bakers adopt adjectives like “artisanal,” Derek simply bakes well-known and well-loved breads and pastries. During the week preceding Easter this year, his bakery case was bulging with Hot Cross buns, classic Easter treats, emblazoned with sugary crosses. The baked apple fritters revealed chunks of apples and cinnamon rolls could hardly contain the ribbons of melted sugar and spice within their creases. All sorts of classic breads filled the wicker baskets: whole wheat, multi-grain, Italian, sourdough, and focaccia breads and rye loaves. The ciabatta was perfect, a hard outside crust around a soft, chewy interior that filled the room with the aroma of caramel when toasted. It’s the kind of ciabatta that enveloped huge wells of butter and jam in pockets created by yeasty bubbles. A new restaurant, The Hillside Farmacy, in East Austin uses Moonlight ciabatta for a mushroom, caramelized onion, Brie sandwich.

Understandably, a visitor to the bakery could become transfixed by the scrumptious goods in the pastry case; but other sights in the small shop reveal other stories implicit in the provisioning of Austin with Derek’s admirable loaves. Piled high to one side, on pallets, were bags of flour awaiting entry to the back of the shop where the flour became bread. Two suppliers’ names identified the source of the bags: King Arthur Flour and Johnson Bros. Bakery Supply. Both purveyors provide histories that add texture to the bread supply chain. They also represent those many other players in the food system that are often over looked in the provision of some of our very basic food products. For the Stilsons, flour and baking pans are the bread and butter of their business.

King Arthur Flour is the oldest flour company in the U.S. Founded in Boston, Massachusetts 1790 by Henry Wood, the company sold flour imported from England and unloaded from British ships as they docked in Boston. The company began milling its own flour and by the 1890s announced its American-grown flour at the Boston Food Fair. Now, after 222 years, King Arthur flour operates from its corporate headquarters in Vermont, ideally suited to the state’s culture of culinary traditions. You can buy industrial bags of flour, like Moonlight Bakery does, or peruse American-made cookie sheets in King Arthur’s catalog. Moonlight, old-school with its line of classic baked goods, seems perfectly aligned with its source of flour from a company named after classic myths with deep historical ties to New England.

Johnson Bros. Bakery Supply Inc. lacks the long historical roots of King Arthur Flour but instead comes to Moonlight with connections to Texas history. Founded in 1994, a mere eighteen years ago, the company headquarters is in Houston. Two brothers raised by parents who ran bakeries in Minnesota and Texas, learned their trade by making doughnuts and decorating cakes. In the 1990s, they formed a company to supply the bakers, including the flour that sits in the front of Moonlight’s bakery shop. Twenty trucks deliver bakery supplies in Texas, operating in Texas and Oklahoma. The two brothers, Kevin and Blaine sell all kinds of bakery supplies, from flour to icing to chocolate for cake fillings.

These bags of flour, some from Vermont, some from Texas, convey an all-purpose, no frills approach to the Stilson’s bakery. They also represent two of dozens of other suppliers that bring paper bags, butter, eggs, cash register paper tape, and light bulbs. They all go into the loaf that Norma and Derek bake. Seems like to appreciate and understand how our food system works, we need to cast a wider net, think more broadly while we think deeply about the food we eat. Our findings may lead us to a much broader landscape that includes surprising participants in the business of feeding urban populations. Cookie sheet manufacturers, the fuel required to transport the sheets, the packing materials, labor, and metals used to produce the sheets, combine in our food networks. One inspired baker in Austin is only one location on the long road traveled by a grain of wheat to the breakfast table. Unraveling this network could be one of the most interesting and revealing projects yet.