by Food+City | Oct 21, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

Trust matters. As we study what makes our food system work, we find that enduring human relationships are the sinews that flex when the system is disrupted. Social media may be our new tool for building relationships, but speed may not replace our old, slow method of building trust.

Transactions based on trust make the food world go ’round. Food producers, processors, and distributors depend upon relationships built over time that result in trusted transactions and confidence in credit, quality, and consistency.

Long-term human networks that took much longer to build might be on the verge of being replaced or at least marginalized by our modern digital social networks. Our tweets and Facebook postings tend towards one-way communication, not two-way exchanges. Would you trust a new banker if the only way you could build trust with her was to receive her Tweets instead of meeting her for coffee?

Tom Standage, the author of A History of the World in 6 Glasses, and The Victorian Internet, just completed his latest historical hack of social media, Writing on the Wall: Social Media, the First 2,000 Years. It’s about time. Social media has been pleading for a historical accounting.

Standage posits that digital social media is similar to the old social networks in many ways. Short, informal messages have circulated for centuries, delivered via papyrus, paper, and in social settings such as coffee houses. Social exchanges became the underpinnings of business relationships and often led to trading practices that have endured until recent times.

Those concerned about the future of our food system are building mobile apps and big data assets with the intent to solve food supply problems through the Cloud. And they may be right. And in fact, we can see the benefits of digital farming already with improvements in precision agriculture and the improvements in resource sharing. But how will Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn build the trust so essential to trade and transactions? Will the speed and one-dimensionality of our modern social media provide enough depth to anchor the system during disruptions such as war and economic downturns? I’d guess that repeated handshakes that bring humans together in the same physical space matter more than repeated shout outs to your favorite supplier.

by Food+City | Oct 13, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

The Radio Lab recently featured a podcast called “Poop Train.” Guaranteed to grab your attention, the title referred to a system used by cities to eliminate human waste water. Surprisingly, we learn from the podcast that it wasn’t until the 1980s that New York City stopped dumping treated human waste into the ocean. Gradually, the treatment facilities improved and the resulting sludge was transported to farmers around the U.S. to dress their fields. Because the costs were so high to transport the stuff, sludge is now being kept nearer New York City, awaiting someone to innovate an inexpensive way to transform human waste to agricultural manure on a scale that makes economic sense.

The idea of spreading human waste on fields that produce food for human consumption, although elegantly circular, if off-putting to some. To others, manure is manure. Entrepreneurs in London during the nineteenth century felt the same.

When the London Embankment project was underway, men known as Gong Farmers, transported human waste to farmers outside London for use on agricultural land. When the railroads came to London, Joseph Balzalgette, the engineer who designed the Embankment sewerage system in the mid-1800s, suggested transporting waste on trains to farmers outside London. The history of this enterprise is told in a book by Stephen Halliday called The Great Stink(http://www.amazon.com/The-Great-Stink-London-Bazalgette/dp/0750925809/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1381715168&sr=8-1&keywords=great+stink+of+london). Maybe it’s time to get the topic back on the agenda for urban planners, big stink or not.

by Food+City | Sep 15, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, History, Stories

While the world watches Syria cross red lines, Syrians contend with breadlines. Hardly a grenade passes through rebel or military hands without making an impact upon the country’s food supply. Collateral damage inflicted on crops and animals rarely reaches consumers of news about the Syrian crisis.

Throughout history, governments have recognized the link between war, food, and national security. The Romans noticed the connection when they sought food sources throughout their empire; the French saw a revolution ignite over bread prices, and in 1812 Napoleon observed the starvation of his army in Moscow, leading to his famous remark that “an army marches on its stomach.”

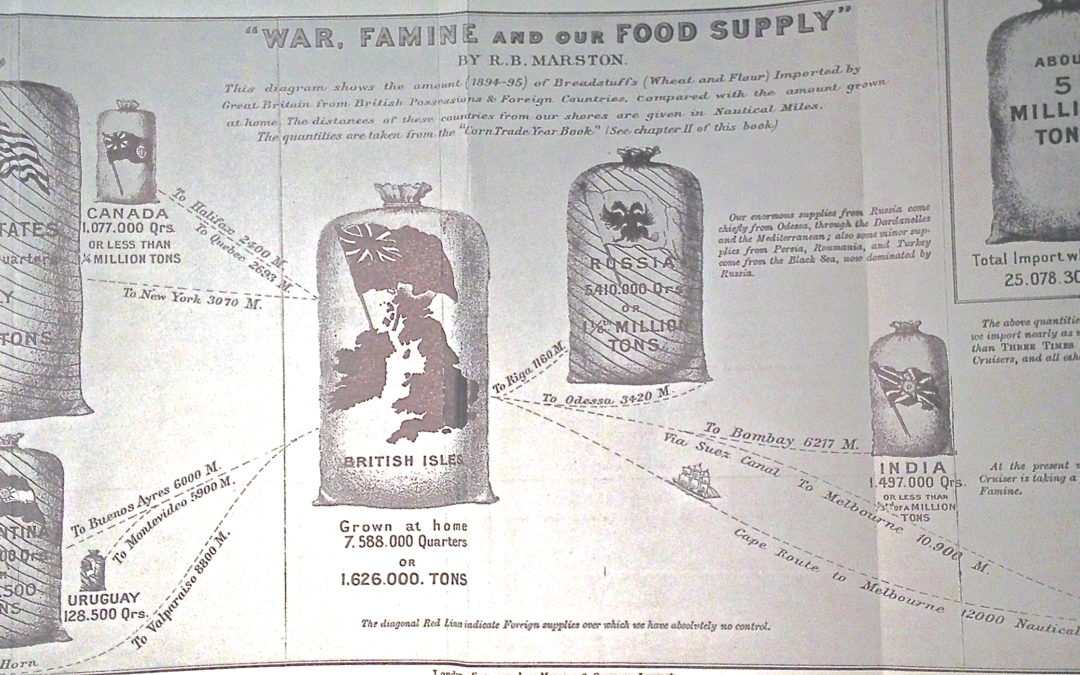

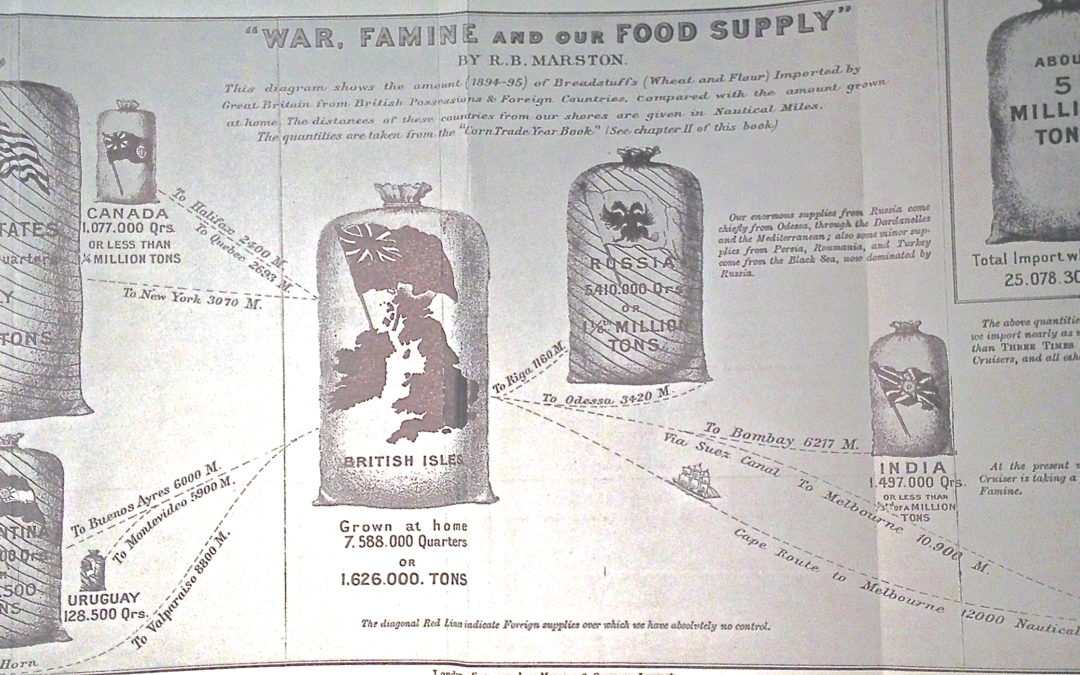

So in 1897, when Robert Bright Marston drew upon Napoleon’s observation to argue for greater food security for Britain, he was well aware of the link between a nation’s ability to feed itself and national security. In particular, he was worried about Britain’s reliance on Russia and the U.S. for wheat and corn. Marston envisioned the construction of grain storage buildings that would enable England to live for three months if a war cut the country off from Russian and American grain. You can see from his illustration how he saw the relationships between grain suppliers and the British grain supplies.

Marston, a British writer known for books about fly fishing, wrote War, Famine, and Our Food Supply to warn Britons that war could disrupt their food supply and somehow bring Britain to its knees. One wonders if urban designers in the early 20th century paid attention to his warnings.

The disruption of Syria’s food supply by civil war has been largely ignored by our media sources but nonetheless grave. While the media talks about casualties from weapons, little is said about deaths caused by famine and poison through the food systems in countries now at war. Few are aware of the destruction of livestock and cropland and the contamination of soil and water over the long duration of some of the modern conflicts.

The ripple effect of unrelenting conflicts is difficult to imagine. The most obvious effect is the breakdown of the infrastructure, especially the transportation of food. In Syria, even the perception of a disruption in the delivery of food causes an increase in black market activity, rising food prices, and higher incidences of hoarding. Pita bread, animal fat, and potatoes quickly disappear into basements and closets. More Syrians freeze and dry food for longer-term storage. As it becomes more and more difficult to transport food to Syria, Syrians look for more localized food sources. Commodities like fuel and flour begin to disappear, creating fears about being able to produce even the simplest but even more essential elements of their diet, flat bread. And, with the potential breakdown of Syrian’s government, comes the loss of state control of bread prices and ingredient supplies.

American cities see the connection between disruptions and urban food supplies mostly caused by natural disasters. New Orleans and New York City are keenly aware of the fragility of food supply chains when a natural disaster such as a hurricane destroys bridges and other food transport networks. In Manhattan, Hurricane Sandy’s impact upon fuel supplies alone immobilized food deliveries.

Cities today are routinely talking about three to five day food supplies, not the luxurious three month supply that Marston was angling for. Whether or not a city needs three days or three months … or three years is a question that needs more attention. Syrians are happy to have three minutes to consume a chemically free meal.

New York wants more than three days of food to keep it afloat in the future. Twelve months would be nice. But who’s to decide and how do we accomplish what Marston argued for in 1897, at least enough food for a country to adapt and find new sources of sustenance?

by Food+City | Sep 8, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

The Blanton Museum in Austin, Texas, is now showing Sam Taylor-Wood’s 2001“Still Life,” a three-minute video of fruit on a plate, rotting. The time-lapse images are transfixing, engaging your senses as you watch fruit decompose, moment by moment. (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BJQYSPFo7hk)

Food and art have enjoyed each other’s company for centuries. Rudolf Arcimboldo’s 16th century painting, “A Feast for the Eyes,” is an classic art/food mashup. (http://media.smithsonianmag.com/images/Arcimboldo-Rudolf-II-631.jpg.)

Food is also fodder for contemporary performance artists and designers. Marti Guimé’s book Food Designing and Marije Vogelzang’s Eat Love portray food in tantalizing, subversive contexts, turning food as material culture into multimedia, multisensory experiences.

At first Taylor-Wood’s plate of pears, grapes, and apples appears static and your eyes search for meaning, observing the stems and small, brown defects of the pears’ skin. And then, as though taking its last breath, the fruit seems to slightly inflate, inhaling one last time before disintegrating, spoiling, rotting, into a final scene where the fruit, consumed by insects, now white, hoary with rot and spumes of gauzy mold becomes a nauseous disgorgement of putrefaction, amoebic shapes insinuating their original form.

How does a video that includes moving images of rotting fruit acquire the title “still life” in the first place? It’s hardly still or a celebration of life. Or is it? “”Still-Life” is part of a Blanton exhibit that describes ordinary objects that are “beguiling, loaded with narrative and metaphor,” which is another way of saying that the works of art aren’t what they seem to be.

A few years ago I visited the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in Boston. The museum had just moved into an audacious building at the edge of the waterfront and was drawing crowds eager to see new exhibits.

One room included an example of “performance art,” a pile of clothing pushed into a corner. Seemed like the emperor indeed had no clothes, at least at the ICA. By the time I returned home from the exhibit I felt compelled to react to what seemed at the time a display of an artist’s complete lack of creativity. But, for a week, I tossed down my clothes each night and took a photograph. By the third night, I was rearranging the clothing, observing where colors and textures overlapped or where the composition seemed out of balance, overwhelmed by a pant leg or disconnected from an orphaned sock.

The surprise came at the end of the week when I posted the gallery of photos here:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/90414796@N05/sets/72157635382777662/

Aha, I had become the perfect participant in the performance of art at the ICA, provoked to react, pushed to think more about the meaning of art. The pile of clothes wasn’t just a pile of clothes. The exhibit beguiled me, like the rotting fruit, just as the fresh apple beguiled Eve, into believing that clothing had other stories to tell.

Seems the convergence of art, science, and food is underway. Meanwhile, I can never look at a pile of clothes or a plate of fruit in the same way, can you?

by Food+City | Aug 29, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

In today’s noisy, scrappy conversation about food, a pitch-perfect note once in a while bubbles to the top. Bee Wilson, a food historian and author, recently brought us one of those sparkling notes in her review of William Sitwell’s new book, A History of Food in 100 Recipes. Wilson writes reviews in The New Yorker and sometimes her own books, such as Consider The Fork, published by Basic Books in 2012.

While offering her thoughts on Sitwell’s attempt to extract historical narratives from ancient recipes, Wilson slips in a short riff about storytelling and the idea that a recipe is a story. As a fictional story, a recipe hints at the possibility of a resolution. A recipe invites a reader to follow a narrative, a set of instructions, with ingredients that have their own character traits along a story arc that evokes both drama and denouement. The setting of the story belies the writer’s own attitude, place, and culture. Recipes can be stories within stories.

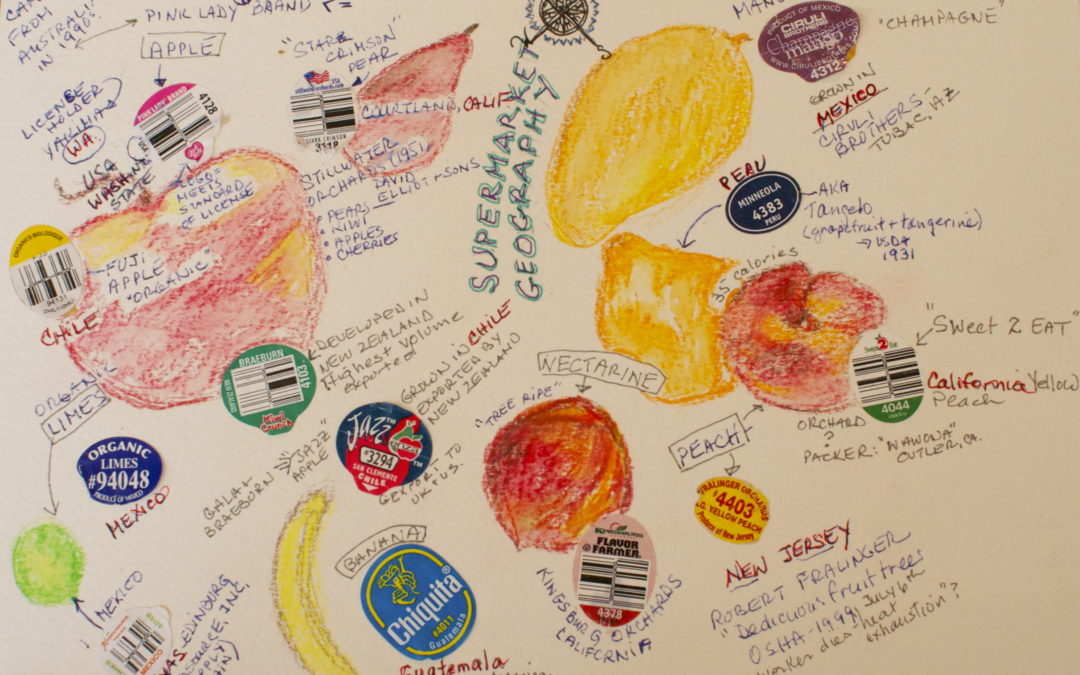

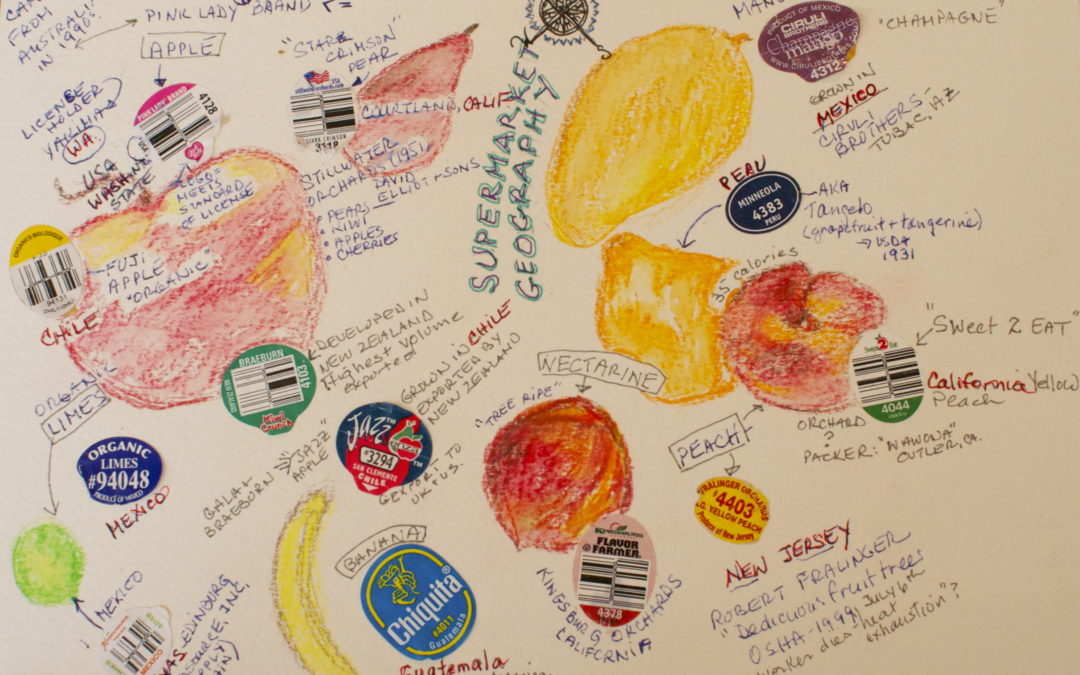

But so can other readable texts, such as those pesky stickers that adhere to the fruit we buy from grocery stores. For a week this summer, I began peeling off PLU stickers from the fruit that I purchased from two grocery stores. PLU stands for “Price-Look Up” and are codes that tell us where our fruit comes from and how it was produced. The codes first appeared in 1990 and are now sometimes accompanied with bar codes. They lubricate the trade of produce around the world.

The codes are easy to decipher: Four digits indicate the probable use of pesticides, five digits beginning with a eight mean that genetically modified organisms were used during production, and five digits beginning with an nine mean that the fruit was produced using organic methods.

I randomly chose the fruit, not intending to buy local or organic or non-organic, but buying what I needed at the time and looked fresh. The stories of these fruits emerged and included the following: None of the fruits were genetically modified. Out of twelve fruits, only two were organically produced, which was surprising since at least half of the fruit came from a Whole Foods Market in Maine. The rest were non-organic and came from California, Mexico, Guatemala, New Jersey, New Zealand, Chile, Washington state, and Peru. Here is my PLU Map.

By looking up the codes, you can sometimes find the names of the growers, packers, family names and histories. Some of the stories that surfaced were personal. One grower had received an OSHA violation for a worker who died of heatstroke while harvesting fruit. Reading the details of the worker’s death, I felt uncomfortable, sensing that these details were not for public consumption. I wonder how this individual’s family would react to the knowledge that someone who casually bit into a nectarine shared the intimate details of his demise. I was left wondering if the grower was somehow responsible for the death, or was the worker already in poor health and in spite of being advised not to come to work, came anyway on one of the hottest days that year in California.

So even PLU stickers reveal stories, like recipes, complete with drama, tension, and resolution. Someday those stickers will be edible and we’ll eat the words of producers, food scientists, and processors.

Stickers, recipes and Bee Wilson’s fine story telling are contributing to my current interest in storytelling. How many ways can you tell a story? What makes a good story? What do you think?

by Food+City | Jun 25, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

Yes, just spent a week logging miles upward and downward. After a week in Paris, I joined my family for a week-long adventure in Bohemia, in Grainau, where the alps gather around the border between Germany and Austria. Three of us competed in the Zugspitz Ultratrail Race set in the shadow of the tallest alp in Germany. I ran 25 miles and my two children each ran 42. But the kicker was the 9,000 feet up and 9,000 down for the kids and 6,000 feet up/down for my distance. In the rain, and fog, and over rocky, slippery trails. I finished in 7 hours 21 minutes, Julia in 12 hours, 10 minutes and Max in 10 hours 49 minutes. A long day, but exhilarating in every sense, wet, rough, fragrant pine trees, and icy snow. It was one of our toughest trail races, mostly due to the wet, steep conditions. The event, known as a mountain trail run, was all about the elevation, not so much the distance. But the mountain came with new friends, stories, and a sense of awe at the group of 1,000 runners that shared the event with us. Most were German, but because of the proximity of the Marshall Center for Security Studies in Garmish Partenkirchen, Americans competed supported by their families waving American flags along the finish line. For our compatriots and the local German runners, the race brought us into sky-piercing mountains, fields of wildflowers, tinkling cowbells, and alpine streams, not to mention crusty, salty pretzels and endless amounts of hot, juicy German sausage. All good, now onward.