by Food+City | Sep 7, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

Critics of our global food system will find the recent news about Walmart in South Africa disturbing. The Wall Street Journal reports that South African food companies are working hard to transform their products and business practices so they can work with Walmart. While this may appear a form of American cultural hegemony, South Africans are anxious to join the global food chain by joining forces with the U.S. food company. One South African food company executive said, “We are desperate not to be left behind.”

Not being left behind is a challenge for a country that has limited overnight food deliveries because of carjackings and whose culinary traditions include such as umgombothi (a beer made from maize). Moving from traditional African food companies to a global food company will likely draw the ire of those who want to keep business and food at home, but modernization will more than likely continue its inroads to the African food system. When Les Halles, a “big box” food store of sorts appeared in Paris during the mid-nineteenth century, Parisians were similarly conflicted between the promise of modernity with the market’s use of new technology (cast iron market hall construction) and the move away from historic food shops that had been serving customers since the ancien regime. Emile Zola, in his 1873 novel, The Belly of Paris, described the new Les Halles market as “some vast modern machine a steam engine or a cauldron supplying the digestive needs of a whole people, a huge metal belly…) Similar to these Parisians, some South African food producers are worried about being drawn unwillingly into a food system that will consume their own business. For the time being, South African food companies seem excited and positive about the prospects for their businesses and for the benefits that their customers will receive through lower prices and more choices.

by Food+City | Jun 27, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

The new exhibit at The New York Public Library, “ Lunch Hour,” is chock-full of artifacts, stories, and memories that will feed your curiosity about meals quickly consumed and forgotten. One enlightening tidbit is the definition of lunch during the 18th century. Samuel Johnson defined lunch “as much food as one’s hand can hold.” (From the “lunch” entry in Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language, 1755.)

Exploring New York City “lunch hour”, the rich displays reveal a complicated tale of time, culinary fashion, and social meanings. Anthropologists and school children will be amused by the wall display of metal lunchboxes irresistible. The entire exhibit covers the evolution of the luncheonette, cafeterias, school lunches, and the power lunch, just for starters. The limited time available for eating the midday meal put pressure on entrepreneurs and customers as industrialization put a premium on productivity at the office and factory.

By the mid-1800s, New Yorkers were finding new ways to eat that took less time out of their workday. The density of New York neighborhoods made it easy to capitalize on the proximity of “luncheonettes” and cafeterias. Old menus from some of these quick-lunch places reveal the expediency and inventiveness required by café owners in order to provide speedy and convenient ways to dine. Restaurant and luncheonette owners used rubber stamps to print the names of new dishes and prices on their printed menus, telegraphing a just-in-time adjustment to the availability of food and the desire to please their pressured clientele.

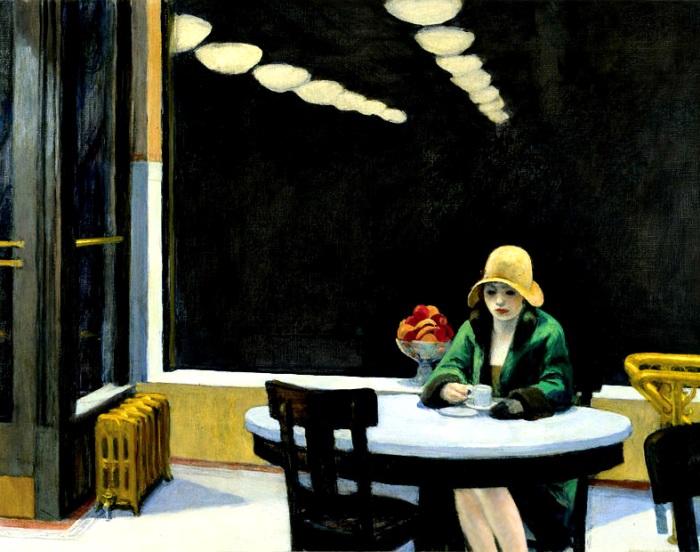

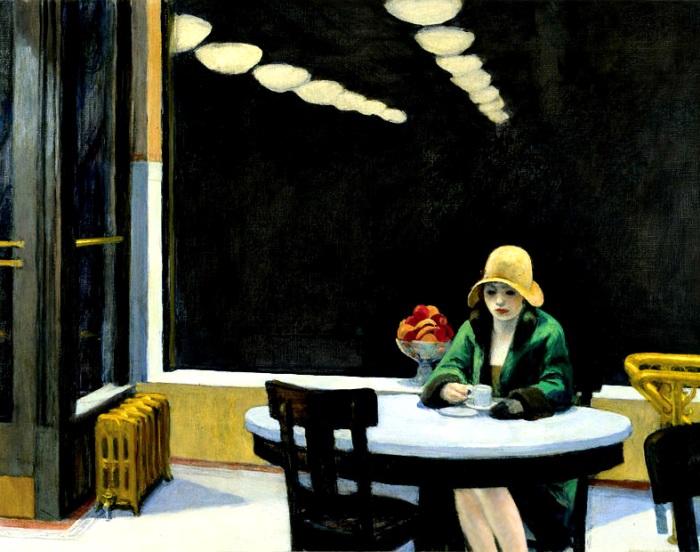

The displays about the New York Automat, the invention of two German immigrants, Joe Horn and Frank Hardart, tell how they launched a factory-like food dispensary that lasted until 1991. Walls of the windowed little boxes, containing such lunchtime fare as macaroni and cheese and fresh doughnuts, are reconstructed in the exhibit, providing a sense of what it must have been like to spin into one of these places with your handful of nickels, the amount required to unlock one of those little doors. Video displays show clips from movies shot on locations that featured Horn and Hardart Automats, including a film that portrayed a budding romance that blossomed between a beautiful woman and her nickel on one side of the boxes and a handsome man on the other side, who whispered his desires through the small portal.

The evolution of the sandwich, including the soft bouncy slices of Wonder Bread, and the invention of peanut butter (invented for children and at first made spreadable by the addition of chile sauce and mayonnaise), add meaning to a lunchtime standby that has recently reinvented itself into a burrito or a wrap.

Charity lunches occupy one room of the exhibit, introduced by urban reformers like Jacob Riis who saw the city fail to provide food for its poorer inhabitants. During the Depression, New York City attempted to solve unemployment by acquiring mountains of apples for the jobless to sell, filling street corners with apple vendors, but only solving the employment crisis until New Yorkers became fed up with apples.

The exhibit concludes with menus and photos from the heady years of the 1980’s “power lunch.” Iconic restaurants such as Sardis, The Algonquin Club and Delmonico’s provided a visible space to conclude business deals and to engage in the art of networking. Restaurant entrepreneurs worked to attract their celebrity clientele, creating lunchtime legends such as Dorothy Parker and Harold Ross.

“Lunch Hour” is a well-designed exhibit and reveals the many layers of New York’s food culture, including names such as Schrafft’s and Chock-full-of Nuts. You will leave with a new appetite for understanding the implications of our digital world. The only notable exception to an otherwise comprehensive display is the food truck. Mobile food, now so popular in today’s urban food scene, began decades ago and its story would complete the telling of “The Lunch Hour. Check out this exhibit here http://www.nypl.org/events/exhibitions/lunch-hour-nyc-0. Lunch Hour continues until February 2013.

by Food+City | Jun 18, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

Austin is bursting with enthusiasm for food. Even better, our city fosters innovative startups that add to the richness and experience of the food scene.

Foodies, food trucks, and fans of food in general have thrived and grown over the last twenty years, driven by the mix of musicians, college students, and artists seeking cheap and delicious food. Thus the food truck phenomena hit Austin first, giving our city a reputation for being a scrappy player in the food scene.

The recent surge of interest in startups and entrepreneurship has encountered the food movement here, creating the ideal climate for food-related incubators fostering the birth of new food companies. One new innovator entering the market is Molly Lindner with her company, Choxolat.

Lindner’s description of the creation of Choxolat offers a glimpse into how her process might provide a model to other innovators who seek access to Austin’s unique and vibrant food culture. Her process includes methodical due diligence, careful gathering and curating of knowledge from experienced mentors, and experimentation with new ideas. Successful entrepreneurs build their companies by paying attention to this process, gathering first-hand knowledge that offers entrepreneurs entry into the business world in ways that give their startups a fighting chance to survive and thrive.

But what is noticeable and a bit unsettling is the number of young startup teams that want instant access to a food scene that is complicated and still emerging here. What these new teams lack is a sense of the importance of process.

While living in Mexico City and working for USAID, she became interested in the coffee business. With connections in Austin, she took a few research trips to explore the local coffee scene. She noticed that Austin’s baristas were doing just fine without her, a potentially disappointing discovery. Except she also observed that these coffee geeks infuse their chocolate flavored drinks with unexceptional syrups. This paradox inspired a different business concept: Lindner’s Choxolat would provide baristas with an equally exceptional and consistent drinking chocolate, called Sip, to match the quality of their coffee.

The process continued and included trips to the San Francisco Fancy Food Show where she found a food business coach. With a coach knowledgeable about launching a food business in tow, Lindner then assembled the rest of her “A” team of specialists: a chocolatier and a public relations and marketing company. These three individuals brought skills that compliment Lindner’s persistent discovery and education.

Why do many startups fail? They fail because they are in a hurry. Many new entrepreneurs are in a rush and forget the importance of not only meeting those in the food scene but of listening to them. Because many entrepreneurs are impatient, they are often motivated more by “running a company” than finding an opportunity for solving a problem. They often startup a business that is long on enthusiasm and short on knowledge.

A blend of three high-end chocolates finely ground into a powder quickly combines with milk to produce a rich dark chocolate drink that combines well with coffee or thrives on its own. Her powdered blend of Belgian chocolate is 60% cocoa with the addition of sugar and Himalayan pink sea salt, her signature Sip drink that is called Dark with Sea Salt.

Lindner and her family are moving to Austin as her drinking chocolate is hitting the stores. She is actually selling more to the local retail market, which has discovered that her blended, powdered drinking chocolate stands on its own. Spicy Spice, Peppermint, and Dark Cherry are some of the other flavors in her line of chocolate powders. And just for fun, her customers, baristas and chocolate-sippers alike, sell her marshmallows, which she describes as like “clouds on a sunny day.” Sip’s chocolate beverages are available at Austin’s farmers’ markets and Austin retail stores such as Whip In and Thom’s Market.

Sip is a product of Choxolat Concepts, Lindner’s company in Austin. Following in the tradition of 17th century European coffee houses, baristas in Austin will now be able to provide their customers with fine chocolate along with their artisanal coffee beans.

by Food+City | May 16, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

Back on their feet after weeks of having their reputation besmirched by tales of pink slime, cattle are drawing attention to the complexities and uncertainties of our food system. Chinese dairies, mad cows, and powdered milk illustrate how the milk and meat industry adapts, pivots, and innovates in a dynamic and rapidly changing global market.

While remotely connected, the occurrence of one mad cow in Tulare, California, powdered milk producers in the US and 25 shiploads of cattle moving from South America to China all point to an intricately connected food system. The production of meat and milk is linked not only to the emotions and ethics of consumers but also to food security crises and global restructuring of supply chains.

Consider the recent finding in California of a cow with mad cow disease (BSE, Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy). A consequence of eating meat from cattle fed animal byproducts, the disease causes brain degeneration in humans. BSE first appeared in North American in 1989. Since then, hundreds of thousands of cases have been detected and animals destroyed both in the US and UK. This recent case only puts cattle and consumers on tenterhooks, awaiting news about further outbreaks. Found on a farm in Tulare County, the cow raised concerns about the possibility that entire herds may be tainted, threatening human health. While the USDA continues its investigations, producers and consumers are left hanging about the impact of this incident. Having just recovered from the pink slime media hysteria, when the meat industry had to retool and pivot around concerns over meat processing, producers worried that this one cow will disrupt their business again.

While this fear lingers, China is concerned about scaling up its own dairy producing industry. More and more Chinese are drinking milk and enjoying ice cream, increasing China’s need for productive dairy herds. Seeing this as an opportunity, farmers outside of China are shipping cattle to China. According to The Wall Street Journal, 100,000 heifers arrived this year from New Zealand, Argentina, and Uruguay in response to a drive to produce a new generation of productive dairy cows in China. Chinese cows don’t produce much milk compared to cows in other countries. Lacking the spirit of innovation inspired by capitalism, Chinese farmers have cows that annually produce four tons of milk compared to nine in the U.S. Imparting years of experimentation and improvement of breeding knowledge, American farmers and others outside China, are sending their intellectual property (cattle) to China, seeing the short term advantage of new markets. In the long term, American farmers should consider the effects of exporting their best breeding stock.

American farmers are responding to this new demand by exporting cows, investing in the modernization of Chinese dairies and developing new products. Chinese producers are turning to the U.S. model of industrial dairy farming and are accepting financial support from such preeminent U.S. investment firms as Kohlberg, Kravis and Roberts.

In addition to shipping cattle to China, American milk producers have found another opportunity in China. U.S. powdered milk producers are retooling in order to satisfy a growing demand in China for milk. With rising incomes and a move towards Western food, the thirsty Chinese cannot quench their desires with Chinese milk and so purchase large amounts of powdered milk. U.S. farmers are changing their own production process in order to make powdered milk with a long shelf life, a requirement for Chinese milk consumers. Since many Chinese families lack refrigerators, the long shelf life is critical. Dairy companies such as California Dairies, a cooperative in Central California, have taken notice and have invested in new technology in order to produce this longer-lasting dry milk.

What these stories tell us is that American farmers are adapting and innovating to constant change and crises in the global food system. And these adaptations surfaced during just one week. One week since these news stories, U.S. cattle futures were already beginning to rebound, responding to the upcoming grilling season and low inventories due to herd reductions from lack year’s drought.

Imagine these adjustments and innovations for hundreds of thousands other subsystems and supply chains within the global food system. How can we connect all the cultural, economic, political and environmental changes that affect our food supply? I suggest we begin by digging deeper into our understanding of the system. Let’s explore those connections during the upcoming months. Want to join me? Add your ideas for who ought to be considered part of our global food system. Farmers, yes. That’s obvious. But what about the producers of ice? Or cookie sheet manufacturers? How far are you willing to go?

by Food+City | May 14, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

You don’t have to listen to Jim and Mike Richardson talk about their farm for very long before you know they are improvers. Their farm is a laboratory for experimentation with forage varieties, poultry houses, pig feeders, and grass-fed beef. Building upon the experience of Jim’s long career as a veterinarian and Mike’s enthusiasm and curiosity about farming, the two of them are well equipped to improve food production in Central Texas.

The Richardson’s innovations join a long tradition of agricultural innovators. During the 18th century, British farmers were also improvers, experimenting with what has been called “scientific agriculture.” The raising of crops and animals drew upon the principles of the Enlightenment, rationalizing what was once only left in the hands of nature, the weather, the whim of the animals left outside to breed. Farmers like Jethro Tull came up with the seed drill; Robert Bakewell came up with a systematic way of breeding livestock. Agriculture moved away from common pastures that were dependent upon human labor to highly productive, enclosed pastures, feeding a rapidly growing British Empire by the 19th century. These new “scientific” farmers were innovators, creating new ways of looking at old knowledge.

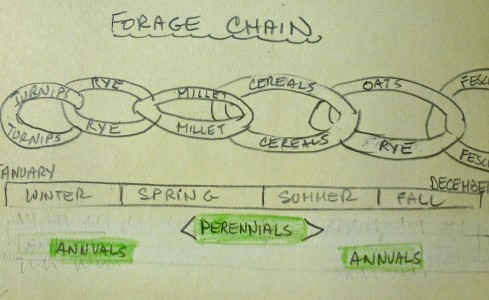

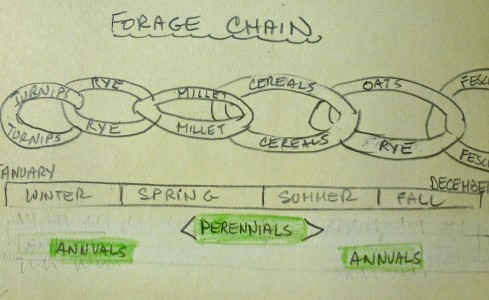

Improvement requires innovation. The Richardsons, 21st century improvers, bring grassfed/finished beef, pastured pork, and poultry to farmers markets and local grocery stores. Captivated by the possibilities of improving the forage chain and exploring ways of growing crops in a drought, they want to balance the use of technology with their desire to remain connected to the land and their customers. (A forage chain is a sequence of grasses and other forage that become ready to use at different times of the year, providing a steady supply of feed for livestock.)

The animals on their pastures are benefiting from the Richardson’s penchant for improvement. Their poultry lives in movable chicken houses, which are frequently moved in order to manage forage and provide grass to the ducks, chickens, and turkeys. Jim and Mike are learning about grading of eggs so that they can improve their farming practices. Instead of moving poultry houses by hand, they use the latest model John Deere farm equipment. And they are well-versed with social media. By talking to other farmers, agronomists, and university extension services, these two improvers are listening for ideas that they could use to make their farm more productive, enhance the quality of their animals and crops while addressing the requirements of the soil and climate of Central Texas.

Mike is intensely aware of the challenge they face with diminishing water supplies and increasing demand from their loyal customers. While he wants to use progressive ideas to improve his farm, he is alert to the potential for moving ahead while leaving his customers behind. The Richardson family thrives on their relationships with customers. They aren’t willing, it seems, to make any changes that would risk these relationships. Balancing the social and financial sides of farming certainly complicates life for these modern day improvers. But they aren’t the first improvers to feel this tension.

Joyce Chaplin, a history professor at Harvard University, wrote about Southern farmers in 18th century who were uncertain about modernizing their practices while at the same time enthusiastic about innovating and adapting to new, more scientific agricultural practices.

One of the reasons, as Chaplin points out, that the Southern farmers were uneasy about modernizing was that while they were moving towards more modern ideas and practices they were enmeshed with traditions, like slavery, for example. In some ways, they were somewhat selective about moving abandoning old ideas. Perhaps those farmers were worried that by moving too fast, rejecting the idea of slavery with too much abandon, they might be responsible for the unraveling of the fabric of southern society. So, they moved away from farming tobacco and began growing cotton, finding a crop that would grow in the depleted soils left behind from years of tobacco farming.

While it may seem like a stretch, to compare a slavery dependent 18th century farmer to a modern day family farmers like Richardson Farms, you can sense the same tension between farmers who want to improve in a complicated world. Those Southern farmers innovated with new crops even though they were slow to reject slave labor. The Richardsons are innovating with new forage systems while reluctant to use traditional practices such as grain-finishing cattle or drilling soil for seed planting.

The reluctance of these improvers might be a good sign, indicating thoughtful innovation that integrates social values, a slight handbrake to the rush to be new.

(For more about those Southern farmers, see Joyce Chaplin’s book An Anxious Pursuit: Agricultural Innovation and Modernity in the Lower South, 1730-1815, University of North Carolina Press.)

by Food+City | May 2, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

Lew Weil, a molecular biologist, grows seaweed for his company, Austin Sea Veggies. In his garage, Lew grows ogo, edible seaweed that looks a little like material for a gelatinous bird’s nest. Where else but Austin, Texas, hundreds of miles away from any coastline, would you find a scientist hunched over an aquarium full of seaweed. Yes, Austin is weird.

But beware of weird. More often than not, an Austinian’s weirdness leads to innovation and an audacious capacity for leapfrogging the rest of us. Lew began his metamorphosis from lab scientist to aquaculturalist when he wondered if there was a more sustainable way to grow agar, the substrate used in Petri dishes for growing microorganisms. Agar comes from polysaccharides in red algae; Japanese and South Asian companies grow most of the algae in farms along their coastlines. Lew thought there might be a way to grow algae and seaweed without relying on coastlines. Since seaweed enters our food chain more often than you may think, like through ice cream and carrageenan-toting apple cider (even your toothpaste has it), Lew foresaw the time when the need for seaweed would outstrip the supply of coastlines. Maybe Lew isn’t that weird.

In 2003, the Food and Agriculture Organization reported that the annual value of seaweed produced for human consumption in the U.S. was $5 billion.[1] But the largest producers are in China and South Asia. After testing and retesting types of seaweed, Lew embraced ogo, from Hawaii and popular with Hawaiians, he moved beyond agar to producing seaweed for human consumption. Enter Austin Sea Veggies. Growing edible seaweed became an obsession for a mad microbiologist. With a degree in biology from Texas A & M, Lew approaches his quest for sustainable seaweed aquaculture using scientific methods with all the geekiness of an agar-ian scientist, now an agrarian scientist.

Lew’s experiments seek an understanding of the seaweed’s growing seasons, its ability to endure temperature oscillations, like the furnace-blast heat during a summer in Texas. Last summer he lost his entire crop and is just now beginning to recover with a new set of “mother” plants. His ogo grows from these plants, its delicate, lacy fronds emerging from the tips of the mother branches. His customers, many of them members of the Hawaiian community in Texas, are anxiously awaiting fresh deliveries of his new crop, typically five to six pounds per month. Restaurants and grocery stores such as Wheatsville, snatch up his “sea veggies” on a regular basis.

But scaling is the entrepreneurs’ vexation. Success brings customer demand, and in Lew’s case, an aquarium in his garage won’t begin to produce enough ogo to satisfy his hungry customers. So look has been talking with other entrepreneurs, including one who has a saltwater quarry in West Texas, an auspicious discovery when oil drillers penetrated the Permian Sea basin, which exists throughout much of the Texas landscape. Salt water gushed into a quarry and sits underutilized for aquaculture, but not lost on Lew. He has a vision for using the saltwater quarry for growing seaweed and shrimp. All he needs is the cooperation of the quarry’s owner, some capital, and a little time off from his day job as a biologist. The scaling bugaboo is the barrier that many food entrepreneurs encounter, some successfully, others not. To get Lew’s food science out of his lab and into sustainable production will take the graces of another entrepreneur, one that turn the Permian Sea into an ogo incubator.

How enterprises like seaweed companies in Austin fit into the global food system, or even more miraculously, into Austin’s food system? As a food entrepreneur, Lew easily fits into Austin’s vibrant food culture. But what about seaweed? And seaweed grown in garages? Steve Jobs began in a garage.