Some things are best left unsaid, and my experience as a pig cloner comes up in conversations only to cause nervous twitching on the part of my listeners. “How”, they wonder, “could someone dedicated to conservation and the environment wander off into the black art of biotechnology?”

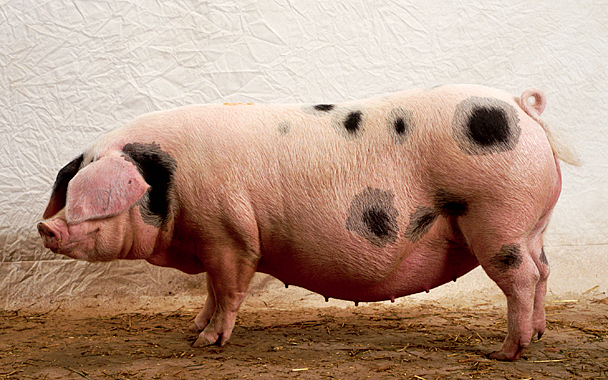

During the years when I was raising heritage breeds of livestock in Maine, I found that one of our precious swine bloodlines was drying up. The farm, founded for the purpose of conserving rare breeds of livestock, operated on the rocky ledge of limited gene material for these minute breed populations. Our pigs, which came from England, had a gene pool consisting of four bloodlines and we had one sow from one of the four lines. She hadn’t had a litter in several years, despite repeated attempts at breeding, coaxing, and the normal veterinary treatments. Genetic diversity for our U.S. herd of Gloucester Old Spots pigs looked prematurely bleak.

Most of us attracted to farming on a large scale come to it with a desire for connection to the earth as an antidote the digitization of modern culture. So the idea of using technology to solve a problem related to animal conservation seemed crazily contradictory for a hands-on farmer.

The seeming contradiction began with a question. What if cloning technology could enable this pig to start all over again? Could we bootstrap her bloodline if a copy of her was able to breed? Might her problems be related to her, not her genetic makeup?

In 2000, Scientific American ran an article, “Cloning Noah’s Ark” and suggested that biotechnology could preserve genetic diversity for animals, which I assumed included domestic animals, such as dogs.

And so did most people. The first customers for laboratories that did cloning were pet lovers who longed for their family dog after the pet’s demise. Cats and dogs were rushed to these labs to reacquire Fido or Fluffy.

But what about a 350-pound hog? At our farm, the staff gathered for a contentious meeting and decision to try cloning to see if a new “copy” of our pig would breed naturally and restart the bloodline. Overcome with moral outrage, some staff quit, others walked gingerly on, but most of us came together with the desire to remain on mission.

Which included the humane treatment of animals. We learned that our sow only needed to have cells gathered from her ear, a process that could cause minimal discomfort. After the skin cells are collected, they are injected into the another sow’s eggs after the recipient’s chromosomes and polar bodies are removed. Once the injected egg contains the skin cells from our pig, an electric shock fuses the skin cell with the egg cytoplasm. The nucleus from our pig cells enters the cytoplasm, fuses, and begins to divide, yielding the development of an embryo. The “fertilized” embryo is injected into a surrogate sow who gives birth to the clone.

We learned about omnipotent cells and conducted a cloning workshop at the farm, offering hands-on experience to the willing and curious. Visitors to the farm explored nuclei and chromosomes under microscopes, winding their minds around complex ideas of ethics and biodiversity.

One of the new cloning companies in 2001 partnered with our farm to explore cloning livestock for conservation, a welcome diversion from Fido and Fluffy. Our sow, Princess, became the proud mother of two piglets, sort of, in April 2002, aptly named Xerox and D’NA. The spots on these pigs were different than those on Princess, providing a lesson in genetic transmission.

The company, Infigen, pioneered the application of cloning technology to breed conservation and was pleased, and so were we as Princess’ offspring went off to produce strapping piglets from her bloodline in subsequent natural breedings.

The uses of such technology can be problematic for the food and agriculture entrepreneurs. GMO technology, for example, taunts those who distrust the aims of technology while beckons to those who see technology as a tool when thoughtfully utilized can break through the limitations of our natural world.

Which shall it be? Could the solutions for feeding our future populations rest somewhere between Princess and the pea?

Author