You don’t have to listen to Jim and Mike Richardson talk about their farm for very long before you know they are improvers. Their farm is a laboratory for experimentation with forage varieties, poultry houses, pig feeders, and grass-fed beef. Building upon the experience of Jim’s long career as a veterinarian and Mike’s enthusiasm and curiosity about farming, the two of them are well equipped to improve food production in Central Texas.

The Richardson’s innovations join a long tradition of agricultural innovators. During the 18th century, British farmers were also improvers, experimenting with what has been called “scientific agriculture.” The raising of crops and animals drew upon the principles of the Enlightenment, rationalizing what was once only left in the hands of nature, the weather, the whim of the animals left outside to breed. Farmers like Jethro Tull came up with the seed drill; Robert Bakewell came up with a systematic way of breeding livestock. Agriculture moved away from common pastures that were dependent upon human labor to highly productive, enclosed pastures, feeding a rapidly growing British Empire by the 19th century. These new “scientific” farmers were innovators, creating new ways of looking at old knowledge.

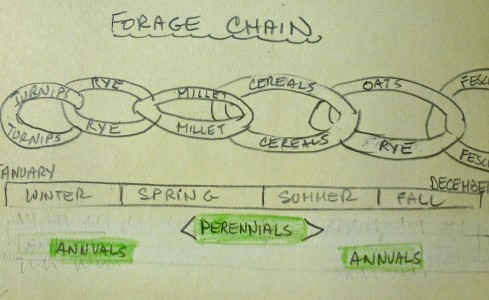

Improvement requires innovation. The Richardsons, 21st century improvers, bring grassfed/finished beef, pastured pork, and poultry to farmers markets and local grocery stores. Captivated by the possibilities of improving the forage chain and exploring ways of growing crops in a drought, they want to balance the use of technology with their desire to remain connected to the land and their customers. (A forage chain is a sequence of grasses and other forage that become ready to use at different times of the year, providing a steady supply of feed for livestock.)

The animals on their pastures are benefiting from the Richardson’s penchant for improvement. Their poultry lives in movable chicken houses, which are frequently moved in order to manage forage and provide grass to the ducks, chickens, and turkeys. Jim and Mike are learning about grading of eggs so that they can improve their farming practices. Instead of moving poultry houses by hand, they use the latest model John Deere farm equipment. And they are well-versed with social media. By talking to other farmers, agronomists, and university extension services, these two improvers are listening for ideas that they could use to make their farm more productive, enhance the quality of their animals and crops while addressing the requirements of the soil and climate of Central Texas.

Mike is intensely aware of the challenge they face with diminishing water supplies and increasing demand from their loyal customers. While he wants to use progressive ideas to improve his farm, he is alert to the potential for moving ahead while leaving his customers behind. The Richardson family thrives on their relationships with customers. They aren’t willing, it seems, to make any changes that would risk these relationships. Balancing the social and financial sides of farming certainly complicates life for these modern day improvers. But they aren’t the first improvers to feel this tension.

Joyce Chaplin, a history professor at Harvard University, wrote about Southern farmers in 18th century who were uncertain about modernizing their practices while at the same time enthusiastic about innovating and adapting to new, more scientific agricultural practices.

One of the reasons, as Chaplin points out, that the Southern farmers were uneasy about modernizing was that while they were moving towards more modern ideas and practices they were enmeshed with traditions, like slavery, for example. In some ways, they were somewhat selective about moving abandoning old ideas. Perhaps those farmers were worried that by moving too fast, rejecting the idea of slavery with too much abandon, they might be responsible for the unraveling of the fabric of southern society. So, they moved away from farming tobacco and began growing cotton, finding a crop that would grow in the depleted soils left behind from years of tobacco farming.

While it may seem like a stretch, to compare a slavery dependent 18th century farmer to a modern day family farmers like Richardson Farms, you can sense the same tension between farmers who want to improve in a complicated world. Those Southern farmers innovated with new crops even though they were slow to reject slave labor. The Richardsons are innovating with new forage systems while reluctant to use traditional practices such as grain-finishing cattle or drilling soil for seed planting.

The reluctance of these improvers might be a good sign, indicating thoughtful innovation that integrates social values, a slight handbrake to the rush to be new.

(For more about those Southern farmers, see Joyce Chaplin’s book An Anxious Pursuit: Agricultural Innovation and Modernity in the Lower South, 1730-1815, University of North Carolina Press.)

Author