by Food+City | Oct 14, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

During my food history class last week, I showed a video of Martha Stewart visiting our farm in Maine. The students were learning about the Agricultural Revolution in Britain. Late 18th century livestock improvers, such as Robert Bakewell, produced what we now call heritage breeds of livestock, such as Cotswold sheep and Gloucester Old Spots pigs. In 1994, I founded Kelmscott Rare Breeds Farm for the purpose of conserving these old-fashioned livestock breeds. Apparently this endeavor piqued Martha’s interest.

As I watched the video with the class, I saw the students smile, beaming with bright, in-the-moment expressions of delight. Some were laughing at the rambunctious sheep and pigs; others were awestruck by our one-ton draft horse named Pete. Their faces reminded me of how magical time this farm experience had been for both my family and myself. We lived on top of a hill on a farm in mid-coast Maine surrounded by expansive views and pastures inhabited by sheep, cattle, pigs, chickens, turkeys, and those indomitable draft horses. I had forgotten, but my students reminded me, of how those days were so full of beauty and intensity, of earthiness and excitement.

My students watched as I introduced Martha to the animals on the farm, chatting on camera about their histories and the importance of their continued presence on farms today. Visitors to the farm strolled through the barns, touched their first sheep, stood in awe as our border collie, Tess, scurried around the sheep to bring into the pasture. I also noticed how visitors, farm staff, and the students in this classroom now never lost their bright and curious smiles. During the time it took to show the video, all of us in that room were in the fields and barns, smelling the sweet hay in the loft, feeling the energy of life on a thriving farm on the coast of Maine. Perhaps we owe Martha a word of thanks for bringing us back to those days in Maine, stunningly bright and full of hope.

You can see the video here: http://www.marthastewart.com/926681/endangered-farm-animals-kelmscott-farms

by Food+City | Oct 10, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

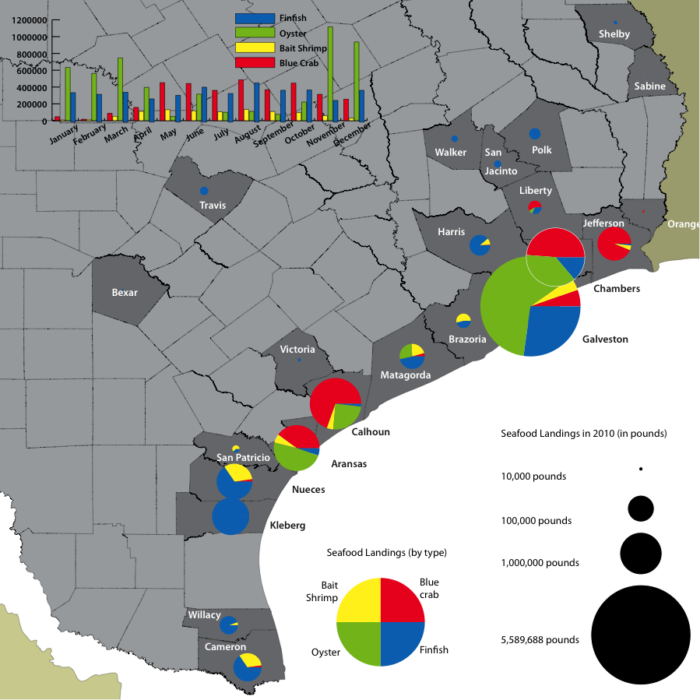

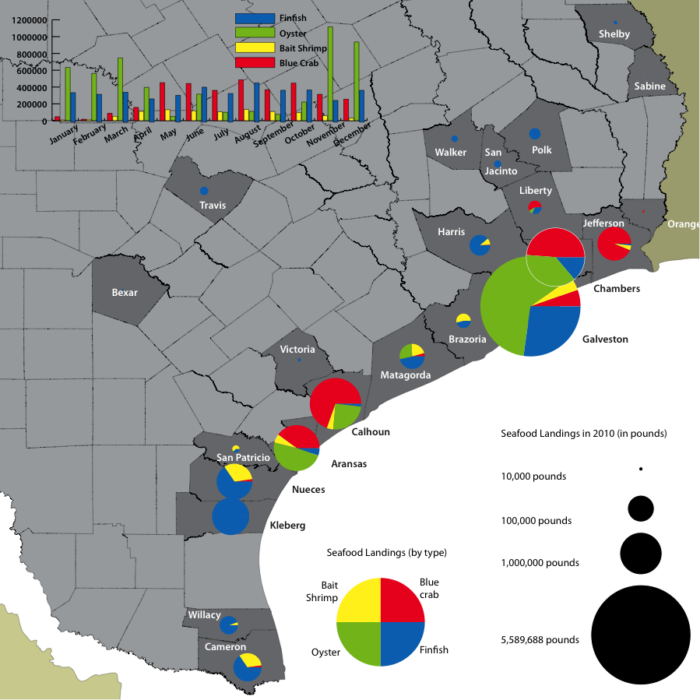

I’ve been working on a food-mapping project for the past several months called Food: An Atlas. The project is a non-profit venture launched by the CAGE (Cartography and GIS Education) Lab at the University of California at Berkeley. The project team intends to self-publish a map created by a network of content providers and cartographers over the web. The idea behind the project is to produce a food atlas in a short amount of time from a broad community of researchers. The Berkeley team, located in the Geography Department, received over 80 map submissions from 10 states in the U.S., South America, and Europe.

Content providers, like myself, provided map data; the project team provided me a cartographer, who happened to be the talented Jeff Ingebritson, a graduate student from the Geography Department at the University of Wisconsin. Together we hashed through my data and his GIS program to create a map of seafood provisioning in Texas.

This was so much fun and an incredibly cool platform. And, I learned what most data mappers already know: You look for data first, then map it. At first, I wanted our map to show how seafood enters Austin, Texas only to find that there is no data for that story. So, I used existing databases and found ways to tell a different story.

The CAGE team plans to publish the atlas online, funded by support acquired through a Kickstarter campaign. See here to add your support HERE.

by Food+City | Oct 5, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

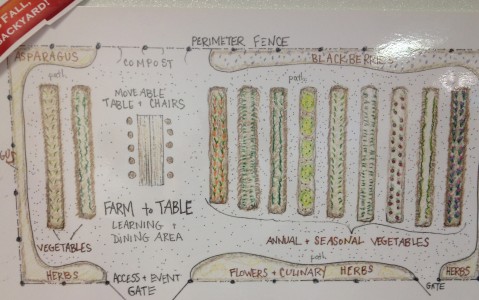

Texas peaches will soon disappear from the Hill Country roadside stands, removing star performers on local restaurant menus such as Peach Melba. Named after an Australian opera singer, Peach Melba was the invention of Auguste Escoffier, a nineteenth century entrepreneur who introduced the ice cream and peach dessert to the Paris Ritz. Demonstrating his creative culinary imagination, he convinced farmers in the Rhone Valley to grow thin-stalked, green asparagus for the British who paled at the white, stocky asparagus on the Continent.

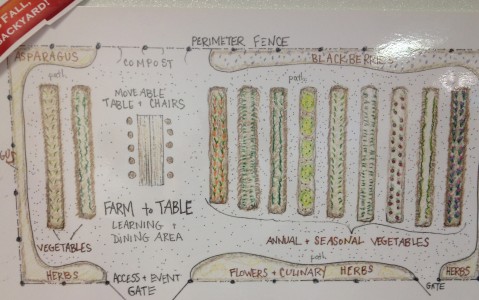

Escoffier’s innovative spirit was evident this week at the Escoffier School of Culinary Arts in Austin where a new Agricultural Learning Center drew the attention of Austin’s food community. Making the connection between food preparation and food production, the school’s new farm-to-table venture will launch culinary students out from the kitchen and into the garden as they learn how to connect what’s in the ground to what’s on their plates. The school is part of a larger movement in food education to connect growing food to making and eating food. Auguste would be delighted, as will be the employers of the new Escoffier graduates. To learn more about the school’s new project, visit http://www.escoffier.edu/.

by Food+City | Oct 1, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

My students have just read about the bread riots in France leading to the French Revolution in 1789. My course is about the history of food in Europe and we explore the ways food connects with change over time. Lots of change begins with a revolution. While we were reading about the women who flung loaves of bread at the king in Versailles, the faces of angry men in Cairo were raging over the price of grain as the Arab Spring portended a new revolution.

Egypt, like other countries in its region, feels the effects of declining grain stocks all over the world. Since the Middle East and North Africa depend so much on imported food, drought and the use of grain for biofuels in places like the U.S. and Russia cause price spikes that ignite protest. Wheat and corn futures are up over 40 percent and the U.S. diverts about 40 percent to the production of fuel for cars.

The women in Versailles demanded that the king find a solution to crop failures and the high taxes placed on bread. The men in Cairo see their governments as unable to feed their countrymen. The connection between food and political stability has been apparent for centuries. But now, the options for governments are not quite as simple as sending the king to the guillotine.

by Food+City | Sep 7, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

Critics of our global food system will find the recent news about Walmart in South Africa disturbing. The Wall Street Journal reports that South African food companies are working hard to transform their products and business practices so they can work with Walmart. While this may appear a form of American cultural hegemony, South Africans are anxious to join the global food chain by joining forces with the U.S. food company. One South African food company executive said, “We are desperate not to be left behind.”

Not being left behind is a challenge for a country that has limited overnight food deliveries because of carjackings and whose culinary traditions include such as umgombothi (a beer made from maize). Moving from traditional African food companies to a global food company will likely draw the ire of those who want to keep business and food at home, but modernization will more than likely continue its inroads to the African food system. When Les Halles, a “big box” food store of sorts appeared in Paris during the mid-nineteenth century, Parisians were similarly conflicted between the promise of modernity with the market’s use of new technology (cast iron market hall construction) and the move away from historic food shops that had been serving customers since the ancien regime. Emile Zola, in his 1873 novel, The Belly of Paris, described the new Les Halles market as “some vast modern machine a steam engine or a cauldron supplying the digestive needs of a whole people, a huge metal belly…) Similar to these Parisians, some South African food producers are worried about being drawn unwillingly into a food system that will consume their own business. For the time being, South African food companies seem excited and positive about the prospects for their businesses and for the benefits that their customers will receive through lower prices and more choices.

by Food+City | Jun 27, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

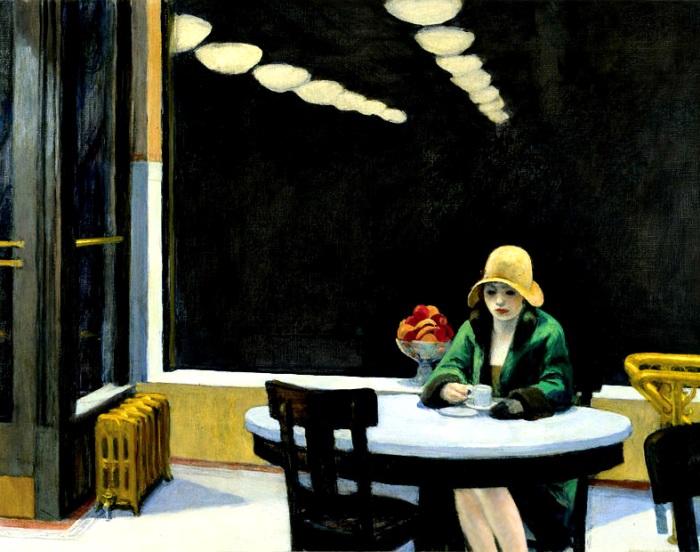

The new exhibit at The New York Public Library, “ Lunch Hour,” is chock-full of artifacts, stories, and memories that will feed your curiosity about meals quickly consumed and forgotten. One enlightening tidbit is the definition of lunch during the 18th century. Samuel Johnson defined lunch “as much food as one’s hand can hold.” (From the “lunch” entry in Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language, 1755.)

Exploring New York City “lunch hour”, the rich displays reveal a complicated tale of time, culinary fashion, and social meanings. Anthropologists and school children will be amused by the wall display of metal lunchboxes irresistible. The entire exhibit covers the evolution of the luncheonette, cafeterias, school lunches, and the power lunch, just for starters. The limited time available for eating the midday meal put pressure on entrepreneurs and customers as industrialization put a premium on productivity at the office and factory.

By the mid-1800s, New Yorkers were finding new ways to eat that took less time out of their workday. The density of New York neighborhoods made it easy to capitalize on the proximity of “luncheonettes” and cafeterias. Old menus from some of these quick-lunch places reveal the expediency and inventiveness required by café owners in order to provide speedy and convenient ways to dine. Restaurant and luncheonette owners used rubber stamps to print the names of new dishes and prices on their printed menus, telegraphing a just-in-time adjustment to the availability of food and the desire to please their pressured clientele.

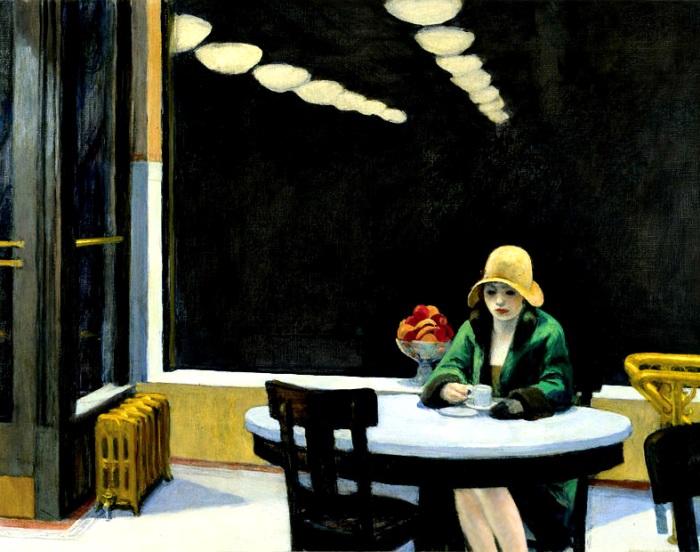

The displays about the New York Automat, the invention of two German immigrants, Joe Horn and Frank Hardart, tell how they launched a factory-like food dispensary that lasted until 1991. Walls of the windowed little boxes, containing such lunchtime fare as macaroni and cheese and fresh doughnuts, are reconstructed in the exhibit, providing a sense of what it must have been like to spin into one of these places with your handful of nickels, the amount required to unlock one of those little doors. Video displays show clips from movies shot on locations that featured Horn and Hardart Automats, including a film that portrayed a budding romance that blossomed between a beautiful woman and her nickel on one side of the boxes and a handsome man on the other side, who whispered his desires through the small portal.

The evolution of the sandwich, including the soft bouncy slices of Wonder Bread, and the invention of peanut butter (invented for children and at first made spreadable by the addition of chile sauce and mayonnaise), add meaning to a lunchtime standby that has recently reinvented itself into a burrito or a wrap.

Charity lunches occupy one room of the exhibit, introduced by urban reformers like Jacob Riis who saw the city fail to provide food for its poorer inhabitants. During the Depression, New York City attempted to solve unemployment by acquiring mountains of apples for the jobless to sell, filling street corners with apple vendors, but only solving the employment crisis until New Yorkers became fed up with apples.

The exhibit concludes with menus and photos from the heady years of the 1980’s “power lunch.” Iconic restaurants such as Sardis, The Algonquin Club and Delmonico’s provided a visible space to conclude business deals and to engage in the art of networking. Restaurant entrepreneurs worked to attract their celebrity clientele, creating lunchtime legends such as Dorothy Parker and Harold Ross.

“Lunch Hour” is a well-designed exhibit and reveals the many layers of New York’s food culture, including names such as Schrafft’s and Chock-full-of Nuts. You will leave with a new appetite for understanding the implications of our digital world. The only notable exception to an otherwise comprehensive display is the food truck. Mobile food, now so popular in today’s urban food scene, began decades ago and its story would complete the telling of “The Lunch Hour. Check out this exhibit here http://www.nypl.org/events/exhibitions/lunch-hour-nyc-0. Lunch Hour continues until February 2013.