by Food+City | Sep 15, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, History, Stories

While the world watches Syria cross red lines, Syrians contend with breadlines. Hardly a grenade passes through rebel or military hands without making an impact upon the country’s food supply. Collateral damage inflicted on crops and animals rarely reaches consumers of news about the Syrian crisis.

Throughout history, governments have recognized the link between war, food, and national security. The Romans noticed the connection when they sought food sources throughout their empire; the French saw a revolution ignite over bread prices, and in 1812 Napoleon observed the starvation of his army in Moscow, leading to his famous remark that “an army marches on its stomach.”

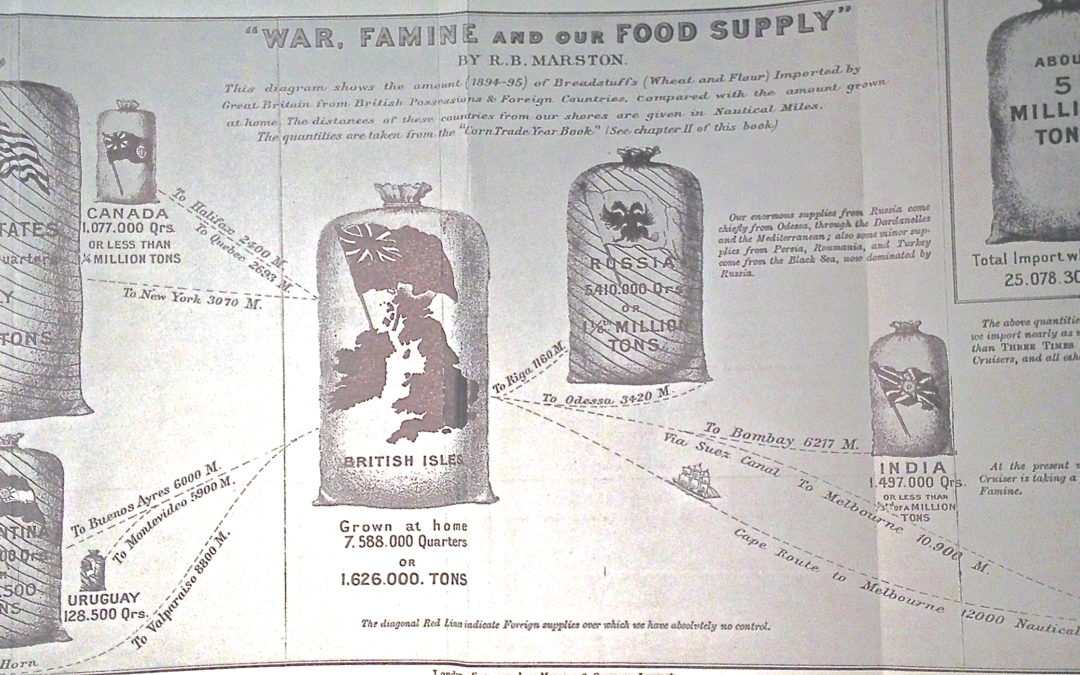

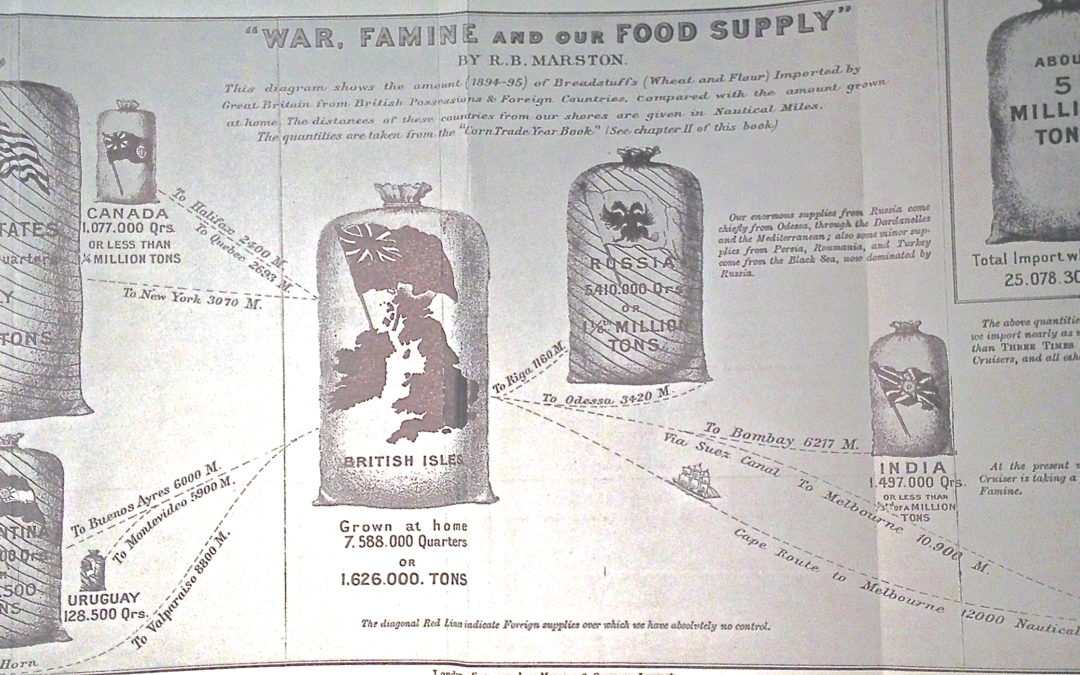

So in 1897, when Robert Bright Marston drew upon Napoleon’s observation to argue for greater food security for Britain, he was well aware of the link between a nation’s ability to feed itself and national security. In particular, he was worried about Britain’s reliance on Russia and the U.S. for wheat and corn. Marston envisioned the construction of grain storage buildings that would enable England to live for three months if a war cut the country off from Russian and American grain. You can see from his illustration how he saw the relationships between grain suppliers and the British grain supplies.

Marston, a British writer known for books about fly fishing, wrote War, Famine, and Our Food Supply to warn Britons that war could disrupt their food supply and somehow bring Britain to its knees. One wonders if urban designers in the early 20th century paid attention to his warnings.

The disruption of Syria’s food supply by civil war has been largely ignored by our media sources but nonetheless grave. While the media talks about casualties from weapons, little is said about deaths caused by famine and poison through the food systems in countries now at war. Few are aware of the destruction of livestock and cropland and the contamination of soil and water over the long duration of some of the modern conflicts.

The ripple effect of unrelenting conflicts is difficult to imagine. The most obvious effect is the breakdown of the infrastructure, especially the transportation of food. In Syria, even the perception of a disruption in the delivery of food causes an increase in black market activity, rising food prices, and higher incidences of hoarding. Pita bread, animal fat, and potatoes quickly disappear into basements and closets. More Syrians freeze and dry food for longer-term storage. As it becomes more and more difficult to transport food to Syria, Syrians look for more localized food sources. Commodities like fuel and flour begin to disappear, creating fears about being able to produce even the simplest but even more essential elements of their diet, flat bread. And, with the potential breakdown of Syrian’s government, comes the loss of state control of bread prices and ingredient supplies.

American cities see the connection between disruptions and urban food supplies mostly caused by natural disasters. New Orleans and New York City are keenly aware of the fragility of food supply chains when a natural disaster such as a hurricane destroys bridges and other food transport networks. In Manhattan, Hurricane Sandy’s impact upon fuel supplies alone immobilized food deliveries.

Cities today are routinely talking about three to five day food supplies, not the luxurious three month supply that Marston was angling for. Whether or not a city needs three days or three months … or three years is a question that needs more attention. Syrians are happy to have three minutes to consume a chemically free meal.

New York wants more than three days of food to keep it afloat in the future. Twelve months would be nice. But who’s to decide and how do we accomplish what Marston argued for in 1897, at least enough food for a country to adapt and find new sources of sustenance?

by Food+City | May 31, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, History, Stories

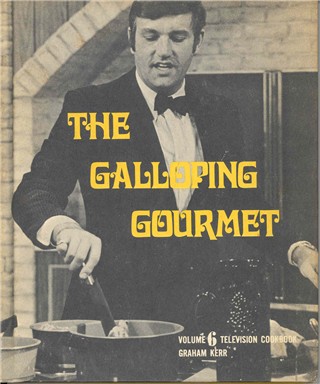

Graham Kerr. The Galloping Gourmet. The man and his brand are inseparable for most of us who got a taste of food programs on TV during the 1960s. Mr. Kerr first appeared on what was known as “experimental TV” on April 16, 1960, before the acclaimed Julia Child made her debut as The French Chef in 1963. But even before the two appeared on TV, Marcel Boulestin, a French chef living in England, appeared on the experimental television programs produced by the BBC during the 1930s. In January 1937, Boulestin demonstrated how to make an omelet for his first program called “Cook’s Night Out.”

Experimentation defined the 1960s, and television was no exception. Early television stations were called “experimental” from the 1920s through the 1950s when broadcast frequencies were not yet commercialized or available to the general public. The BBC’s 1937 program guide reads like a listing of experiments interspersed with articles touting the latest developments in broadcasting technology.

Far from experimental was the decision by both Boulestin and Kerr to begin their programs with an omelet. I asked Kerr why an omelet was the star attraction for his own television debut. He suggested that it was a dish that most viewed as complicated but that, with simple instruction, would enable viewers to achieve a quick victory in their own kitchens.

Watching an omelet take shape during these early years, those who could afford the new Marconi-EMI televisions required good eyesight. The TV had a screen size of only five to eight inches, miniscule compared to our high-definition 152-inch screens.

Why was food one of the first topics to appear through this experimental medium? It may be that the broadcast spectrum became a means for popularizing culinary skills as a way for consumers to save money. Before the WWII, middle class families often left culinary skills to their own chefs or ate at restaurants. The names of the early broadcast programs reflected the idea that a housewife prepared a good meal when her household staff took the night off. And before the war, during the 1920s, books and radio broadcasts included programs that suggested ideas for saving money, such as one program in 1927 called “Wastage in the Kitchen.”

These early years in broadcast are full of experimentation and enthusiasm. Mr. Selfridge, and American entrepreneur who brought Selfridges department stores to England (first one opened in 1909) the focus of a new Masterpiece Theater program currently running on PBS. Henry Gordon Selfridge introduced the first televisions in his department stores in 1927 with John Logie Baird, a Scottish inventor who is often called the “father of television.” Selfridge, an innovative impresario, was much like Graham Kerr, who began his television programs by running through the audience and vaulting over a couch. His wife, Treena, brought her experience in London theaters and pantomimes to choreograph Kerr’s kitchen presence on TV.

These early entrepreneurs, Boulestin, Kerr, and Selfridge should inspire us to think beyond our contemporary food programs and find new ways to popularize culinary skills and good food. Some early efforts are appearing on website and through software applications. But it will be the sparkling personalities and creativity that will engage us anew, much in the way of Julia Child and Graham Kerr.

by Food+City | Apr 1, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, Future, History, Stories

Some things are best left unsaid, and my experience as a pig cloner comes up in conversations only to cause nervous twitching on the part of my listeners. “How”, they wonder, “could someone dedicated to conservation and the environment wander off into the black art of biotechnology?”

During the years when I was raising heritage breeds of livestock in Maine, I found that one of our precious swine bloodlines was drying up. The farm, founded for the purpose of conserving rare breeds of livestock, operated on the rocky ledge of limited gene material for these minute breed populations. Our pigs, which came from England, had a gene pool consisting of four bloodlines and we had one sow from one of the four lines. She hadn’t had a litter in several years, despite repeated attempts at breeding, coaxing, and the normal veterinary treatments. Genetic diversity for our U.S. herd of Gloucester Old Spots pigs looked prematurely bleak.

Most of us attracted to farming on a large scale come to it with a desire for connection to the earth as an antidote the digitization of modern culture. So the idea of using technology to solve a problem related to animal conservation seemed crazily contradictory for a hands-on farmer.

The seeming contradiction began with a question. What if cloning technology could enable this pig to start all over again? Could we bootstrap her bloodline if a copy of her was able to breed? Might her problems be related to her, not her genetic makeup?

In 2000, Scientific American ran an article, “Cloning Noah’s Ark” and suggested that biotechnology could preserve genetic diversity for animals, which I assumed included domestic animals, such as dogs.

And so did most people. The first customers for laboratories that did cloning were pet lovers who longed for their family dog after the pet’s demise. Cats and dogs were rushed to these labs to reacquire Fido or Fluffy.

But what about a 350-pound hog? At our farm, the staff gathered for a contentious meeting and decision to try cloning to see if a new “copy” of our pig would breed naturally and restart the bloodline. Overcome with moral outrage, some staff quit, others walked gingerly on, but most of us came together with the desire to remain on mission.

Which included the humane treatment of animals. We learned that our sow only needed to have cells gathered from her ear, a process that could cause minimal discomfort. After the skin cells are collected, they are injected into the another sow’s eggs after the recipient’s chromosomes and polar bodies are removed. Once the injected egg contains the skin cells from our pig, an electric shock fuses the skin cell with the egg cytoplasm. The nucleus from our pig cells enters the cytoplasm, fuses, and begins to divide, yielding the development of an embryo. The “fertilized” embryo is injected into a surrogate sow who gives birth to the clone.

We learned about omnipotent cells and conducted a cloning workshop at the farm, offering hands-on experience to the willing and curious. Visitors to the farm explored nuclei and chromosomes under microscopes, winding their minds around complex ideas of ethics and biodiversity.

One of the new cloning companies in 2001 partnered with our farm to explore cloning livestock for conservation, a welcome diversion from Fido and Fluffy. Our sow, Princess, became the proud mother of two piglets, sort of, in April 2002, aptly named Xerox and D’NA. The spots on these pigs were different than those on Princess, providing a lesson in genetic transmission.

The company, Infigen, pioneered the application of cloning technology to breed conservation and was pleased, and so were we as Princess’ offspring went off to produce strapping piglets from her bloodline in subsequent natural breedings.

The uses of such technology can be problematic for the food and agriculture entrepreneurs. GMO technology, for example, taunts those who distrust the aims of technology while beckons to those who see technology as a tool when thoughtfully utilized can break through the limitations of our natural world.

Which shall it be? Could the solutions for feeding our future populations rest somewhere between Princess and the pea?

by Food+City | Feb 26, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, History, Stories

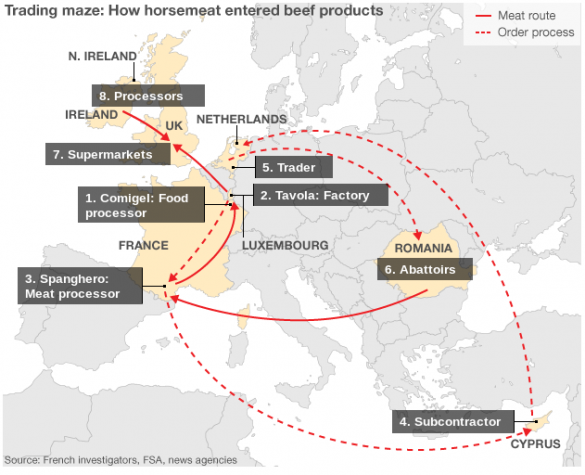

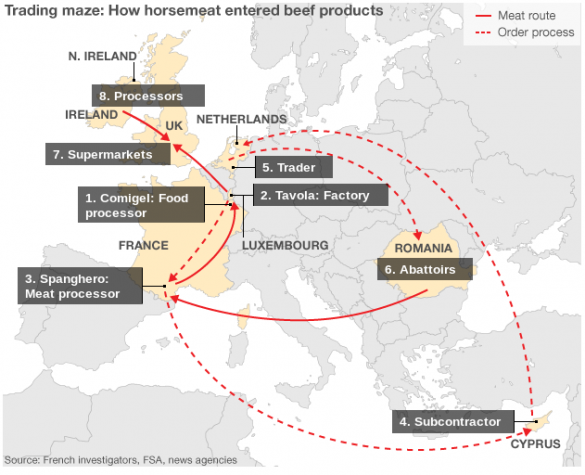

The daily revelations emerging from the discovery of horsemeat in lasagna purchased in Ireland reveal the complexities of our food system. When EU health commissioners tracked down the source of the horsemeat, they found a trail that passed through multiple countries, processors, dealers, brokers, Romania, England, Cyprus, Poland, the Netherlands, and in some cases, through illegal hands.

Since much of our meat is processed, ground up, blended with flavorings, shaped into meatballs and stuffed into sausage casings, each step closer to our plates creates opportunities for processors to succumb to pressures from consumers who want cheaper meat in poor economic times. And this poses a challenge to regulators and concerned consumers who want safe and uncontaminated food.

The current kerfuffle about horsemeat Europe’s food supply chain reveals our persistent concern over what one Victorian writer, Andrew Wyntner, called “culinary poisons.” And todays heightened awareness of food sourcing only raises the steaks over public confidence in our global food system. Frederick Accum wrote in 1820 about food adulteration that he found so ubiquitous in Victorian London. Later, in 1848, John Mitchell lauded the advances in the uses of chemistry to detect the addition of substances that “diminished its real strength without altering its apparent strength. He called this kind of adulteration “the deadly kind.” Andrew Wyntner in “Our Peck of Dirt” claimed German sausages were so contaminated that he called them “poison bags.”

Photo source: http://eluminix.linuxbsdos.com/horse-meat-gate-sweeping-across-europe/

The discovery of horsemeat in Ireland was upsetting on several levels. Not only did the revelation raise questions about food safety and transparency, the mingling of equine with bovine clashes with cultural identities. The British have never been that keen to eat horses while the rest of Europe has assimilated horsemeat into its culinary repertoire. The consumption of horsemeat in France was legalized in 1866 on the eve of the Siege of Paris. While the French have Escoffier included horsemeat in his repertoire claiming that, “Horsemeat is delicious when one is in the right circumstances to appreciate it.” Clearly, he wouldn’t approve of the current circumstances.