How the Bodega Gets the Banana

Like most New York City bodegas, Brooklyn’s 6th Ave. Deli is a practical place.

The narrow aisles in the bodega — the Big Apple term of endearment for the independently run corner stores that trade in a little of everything — are stocked with a dizzying display of the humdrum goods that shop owners know will sell: batteries, king-sized Butterfingers, garbage bags, potato chips, Powerball tickets and, sitting on the floor by the sandwich counter, a 40-pound case of bananas.

Counterman Eddie Gvd, who is originally from Yemen, often runs the register dressed in a tidy white apron. He will sell each of these ubiquitous yellow fruits for between 20 and 35 cents, lowering the price the closer their color deepens to fully brown. Since 6th Ave. Deli usually pays $20 to $25 per case, around 100 pieces of fruit, those bananas bring in just pennies of profit.

Gvd may be able to double the store’s money on candy bars, but he treats bananas like a super-market’s milk and eggs — as a loss leader, an item priced at or near cost in order to bring in buyers for the $1 bottles of Poland Spring that cost the bodega just 17 cents.

Plus for Gvd, selling freckled loosies on the counter for a quarter is just the way the bodega banana business works. The fellow who delivers the bananas to Gvd and a handful of bodega owners pays maybe $16 to $17 per case to a wholesaler, who bought them for a dollar or two less, and so on down the chain. “At least six to seven make a living off it,” says Gvd. “Everybody makes money.”

Gvd’s math isn’t that far off, considering the three-week journey each banana makes to his store. It is a produce paradox that while bananas might seem like an all-American fruit—ubiquitous and inexpensive, they beat out apples, oranges, grapes and strawberries in per capita consumption, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture — they always come from somewhere else, like most New Yorkers.

It requires a host of middlemen — growers, exporters, cargo ship operators, importers, trucking companies, wholesale produce sellers and delivery drivers — to bring bananas up from the humid plantations that flourish in the equatorial zones of Central and South America. They travel by cargo ship, through the Panama Canal if they’re coming from parts of Columbia or Ecuador, then up the Atlantic Ocean to industrial harbors like the Port Newark–Elizabeth Marine Terminal in New Jersey, the largest commercial dock on the East Coast.

Then, after a stint in humble storage centers and ripening rooms hidden in the industrial edges of the Bronx, New Jersey or Long Island, the bananas take their final ride through the city. The majority of them will travel in an army of plain white box trucks with hand-stenciled names like D&J Tropical Produce or D&B Deli Man. They drive from store to store and double-park while their drivers hand over cases of quickly expiring fruit to bodega clerks like Gvd — beloved brands like Chiquita and Dole, but also bunches with lesser-known names and perhaps lower price tags, like El Manaba, Bonita, Bello, Royal Gold and a recent upstart called Selvatica.

Remarkably, no one throws a ticker tape parade to announce the arrival of these exotic fruits, and within 24 hours, most bananas change hands — sold for just three for a dollar, or 79 cents a pound — for the final time.

ARE BODEGAS AT RISK?

The first bodegas were small groceries opened by Puerto Ricans and Dominicans, hence the use of the Spanish term bodega, which refers to a small grocery. Today, according to Jack Sagen of Jetro Cash & Carry, a food-service supply store that caters to bodegas, the owners are now primarily Dominican, Mexican and Arab. Recently, a dramatic increase in rents has led to a decrease in bodegas in upper Manhattan, according to the New York City-based Bodega Association of the United States, but for now, they still play a necessary role in many other city neighborhoods where other food options remain scarce. They are still widely considered one of the most iconic components of New York City life.

THE BUSINESS OF BANANAS

That the banana is a truly a modern agricultural marvel — remarkably affordable, fast-ripening, found in pristine condition for sale every day, everywhere, all year long — is a logistics miracle that has largely gone unnoticed by most New Yorkers.

Few are more aware of this complicated yet largely invisible process than Joe Palumbo. For the past four decades, Palumbo has been peddling produce, the first two delivering to markets and bodegas, the second running Top Banana, a wholesaler in the South Bronx that sells Dole, Del Monte, Chiquita and Bonita bananas, as well as Selvatica plantains and dozens of other fruits and vegetables. He bought the business from the Strik family in 1995: “I was a customer,” he says. “I used to tease them that I’d buy it…then one day they called me and said they were ready.”

Top Banana — whose motto is still “Strik-ly the best” and whose old-fashioned logo features a gorilla chasing after a banana that just lost its top hat — is a ripener, a required stop for every banana before it arrives at a bodega, fruit stand or grocery store. What Palumbo purchased from the Striks wasn’t their delivery routes, distribution network or a banana brand — the family didn’t own any of those — but their warren of refrigeration rooms.

Bananas we buy in the United States are nearly all a resilient monocropped cultivar called the Cavendish. Multinational corporations grow this sturdy species on large plantations in tropical places like Guatemala, Costa Rica, Honduras, Nicaragua, Colombia and Ecuador. Even so, to get the bananas from there to here before they turn to mush, they must be picked bright green, bitter and hard. They are refrigerated during transport via shipping containers on cargo ships and then ripened only once they hit New York.

Though many varieties of bananas are cultivated for sale around the world — and many would argue that most are even better tasting than the Cavendish — the American export market is literally built around the breed because it withstands travel and, more importantly, is resistant to a disease that decimated the tastier Gros Michel cultivar in the 1950s.

Monoculture — where just one kind of plant is cultivated — makes the crop more susceptible to disease, but it also means the farming process is extremely efficient: Plants are the same height at harvest and they mature at the same rate, so fruits are all the same size when they’re separated into bunches and put into a box.

Under a seemingly endless canopy of Cavendish leaves, rubber-booted workers harvest the bunches by hand with machetes, removing enormous hanging stalks that each typically hold hundreds of bananas growing in semi-circular groups of 10 to 20 fruits. Together, they look like upside-down umbrellas. (The banana is actually a flowering plant, and its trunk is technically a stem. Botanically speaking, the banana fruit itself is one big berry.)

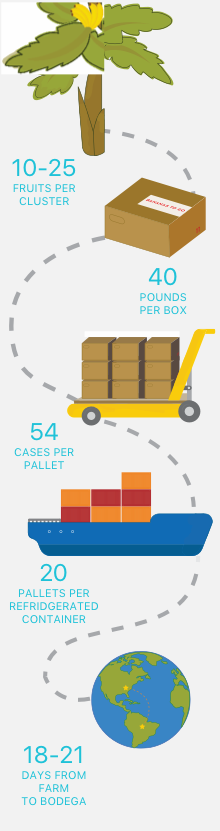

Growers like to refer to the groups as “hands” — the word banana is from an old Arabic term meaning “finger” — which are split up by plantation workers into what Americans fondly call bunches. Bunches are washed, tucked into a branded plastic bag perforated with holes to let in air and placed into a 40-pound cardboard case.

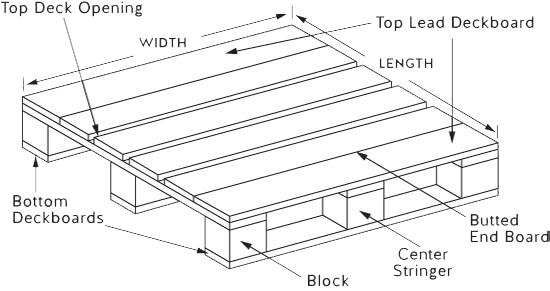

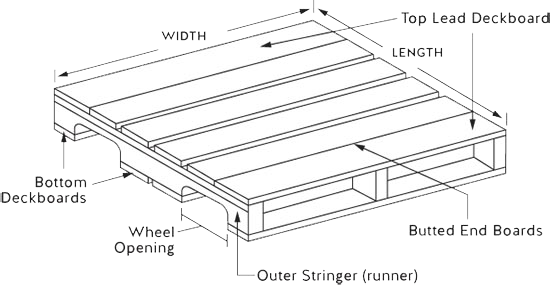

Fifty-four cases of bananas are loaded onto a pallet. Twenty pallets are forklifted into a refrigerated shipping container, and then those 40,000 pounds of bananas join hundreds more containers — loaded both with more bananas and some other exported goods — on a docked cargo ship readying for its journey to non-banana-growing countries.

All told, it takes just 18 to 21 days for those bananas to go from plantation to bodega, says Palumbo, a Brooklyn native who bears a faint resemblance to a young Rodney Dangerfield and shares his penchant for comedic delivery. That and his banana expertise have landed him recurring appearances on the “Produce Pete” segments on WNBC Channel 4 Television in New York, where he has talked about how to properly open a banana or use the inside of a banana peel to shine shoes.

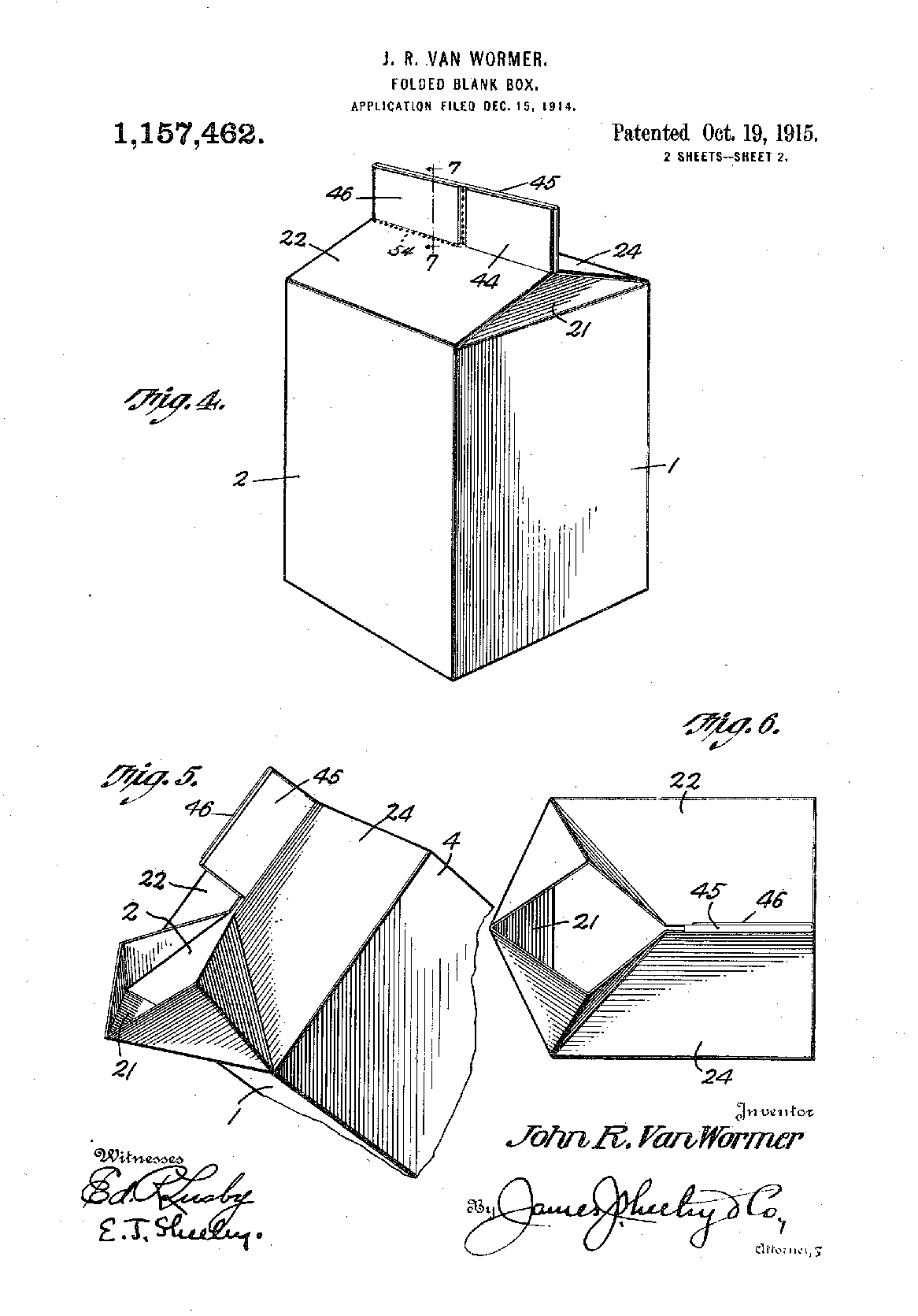

THE BANANA’S TRIP FROM FARM TO BODEGA

One Con of Monoculture

Some who monitor the banana industry, and the recent outbreaks of a new strain of disease known as Race 4, worry that the Cavendish will soon join the Gros Michel in the annals of commercial extinction. Monoculture makes the crop more susceptible to pests or pathogens, which can easily be delivered via soil or on the clothes of a visitor. One suggested solution lies in polycropping of many banana breeds, an exciting thought for those seeking diverse banana flavors.

An employee checks the inside of a banana for ripeness.

WAKING THE CHILDREN

A century ago, says Palumbo, bananas were brought in on the stalk and stored in “banana cellars.” Refrigeration revolutionized the business, as did the invention of the pallet and forklift. Until about 30 years ago, most ripening systems were refrigerated rooms with fans to circulate air around the bananas.

“Bananas are like children,” says Palumbo. “They have to be put to bed, and they have to be woken up.”

Waking the banana has become more technologically advanced over time, though temperature still provides the basic alarm clock. Today’s newest systems — Top Banana built four in the past few years, in addition to maintaining 12 older models — feature computer-controlled, multi-story, pressurized ripening rooms with built-in airflow. Each room can hold two-and-a-half containers worth of bananas at a time.

Not only is the ripening process more consistent — and designed to ripen tens of thousands of bananas in about a week — it is now possible to remotely track humidity, delivery of ethylene gas and airflow through the boxes. Like the bags, the boxes are punctuated with holes to aid the process. The crew even knows the temperature of the fruits themselves, thanks to pulp thermometers that are plunged into the flesh. “I can even see it on my phone if I have to,” says Dan Imwalle, who has worked for Top Banana for eight years.

Even so, the skill and experience of a professional ripener like Imwalle is important, notes Palumbo. “No load is the same,” he says of the refrigerated shipping containers that arrive at his loading bays directly from the ports. Each shipment has bananas at different stages of ripening, and his employees can quickly determine how quickly they are ripening and what the sales forecasts are from day to day. They’ll sort the containers based on how quickly or slowly they need to get the bananas where they need to go.

“Each morning I spend 20 minutes touching, feeling, looking,” says Imwalle. He usually wears custom Top Banana RefrigiWear jackets to keep him warm inside the ripening rooms, which typically hover somewhere between 56 and 67 degrees, depending on the season.

Like most ripeners, Imwalle thinks about a banana in roughly seven stages, which are helpfully listed on a color-coded guide put out by each brand. Though the color for each stage differs slightly for each brand of banana — a fact that both amuses and frustrates Palumbo — the ripeners get them at one (very green) and sell them to markets or distributors somewhere between three and five (when they have some green, but also some yellow). American customers usually eat bananas between a four and a seven, when they are sweeter, have more nutrients and are just beginning to freckle.

In New York City — where Africans, Jamaicans, Indians and others eat off-the-boat green bananas, and banana bread takes care of the brown ones — it’s fair to say that every color is desired by someone. Groceries and big markets buy bananas on the greener side, because they know boxes will sit around their basements and bunches will sit around in their customers’ kitchens. Bodegas usually buy bananas on the turn from green to yellow, because their customers will eat them right away. The overall goal for a ripener or wholesaler? Not to have too many or too few of the colors at any given time.

MUSA

One of two or three genera in the family Musaceae; it includes bananas and plantains. Around 70 species of Musa are known, with a broad variety of uses.

Beyond 4011

Most Americans typically eat only one type of musa — the botanical genus of bananas, including plantains. The commercially sold varieties are all hybridized, cultivated members — but around the world the fruit is cultivated and sold in many flavors and forms, some now centuries old. There is a chunky banana cultivar called Latundan that has a tart-apple flavor, and red-skinned bananas with pink flesh. For those lucky enough to live in banana-growing regions, you can also still find the original wild musa, some creamy and sweet, some largely inedible thanks to their tiny size and large seeds.

THE BEATING HEART OF THE NYC FOOD SYSTEM

Palumbo has plenty of colleagues in the ripening business, many of them with more ripening rooms. They include EXP Group, a New Jersey company that imports Latin American produce including many bodega-bound bananas; J. Esposito & Sons, a 60-year-old company from Brooklyn whose third generation of owners just built new ripening rooms on Long Island; Yell-O-Gold, located just outside of Boston; and Banana Distributors of New York, just around the corner from Top Banana. Each ripener also gets its bananas from various ports in the Northeast. Many of Top Banana’s brands come through the port in Wilmington, Delaware, for example, while J. Esposito & Sons gets its bananas at one of the few working ports in Brooklyn, ripens them in Long Island, then trucks them back to the city.

What makes Top Banana unique is that it is the only ripener in Hunts Point Produce Market, the city’s 48-year-old, 113-acre cooperatively owned commercial distribution center in the South Bronx. Surrounded by yards of battered, barbed-wire-topped fencing, the produce market is like a city unto itself, albeit one that looks like an Eastern European post-war public housing project. Cars have to pay $5 to a security guard at a flank of tollbooths to enter, unless the driver has a pass. The complex consists of four long, low-slung, rectangular buildings that are essentially a series of refrigerators and truck bays. The market has its own private rail yard and, from the wee hours of the morning until midday seven days a week, a vast parking lot bustling with fast-moving tractor trailers.

The produce market, as well as smaller dedicated markets for seafood and meat, make up New York City’s 329-acre Hunts Point Food Distribution Center, the beating heart of the city’s food system. The produce market’s website says it generates $2.4 billion annual in sales with 10,000 employees from 55 countries and 49 states. That’s why Banana Distributors of New York is just around the corner on Drake Street, along with companies like Arugula King, Mr. Hand Truck, Jetro Cash & Carry and also Big Farm Wholesale, which is one of many smaller produce resellers who will buy bananas from a ripener and re-sell them for maybe $14 a case, up or down a few dollars depending on how much quickly browning fruit they are sitting on.

BANANA RIPENESS CHART

Bananas are ranked in stages of ripeness from from 1 (very green) to 7 (with many brown spots). Distributors and bodegas buy them between 3 and 5 and most American consumers eat them between 4 and 7 when they are sweeter and have more nutrients.

What brain-tickling books, podcasts, movies or YouTube channels are you enjoying right now? Tweet us

What brain-tickling books, podcasts, movies or YouTube channels are you enjoying right now? Tweet us

DELI MAN

DELI MAN

Clover

Clover

GASTROPOD; 99 PERCENT INVISIBLE

GASTROPOD; 99 PERCENT INVISIBLE