Rio’s Recipe for the Olympic Games

The usual weather in Rio de Janeiro during winter is somewhere between 71 F and 86 F. Around 9 a.m. in late July, the sun shines strong on the horizon. Rather than enjoying the warm winter weather last year, Romano Fontanive, the executive chef at Sol Ipanema Hotel, was exasperated.

That’s because two weeks before the Olympic Games began last August, he was dealing with a significant schedule change: having to purchase food for the restaurant at 7 a.m. instead of at midnight. The shift had more consequences than simple inconvenience. No air conditioning system can prevent what the heat, sun and long lines of traffic in Rio can do to a lettuce leaf at that time of day.

The chef had to stop buying food during the cooler temperatures of night because the Ceasa Market, the most important food market in the city, which provides 80 percent of everything consumed there, changed its working schedule during the Olympic Games from 12 a.m.–10 a.m. to 7 a.m.–5 p.m. Rio’s city government implemented restrictions for truck circulation during the 30-day event (including the Paralympics). With 800,000 tourists in the city, one of the government’s biggest concerns was to ensure fluid traffic for visitors. Unfortunately, the solution that eased road congestion created a nightmare for the supply chain of food and other goods. “I lose approximately 30 percent of the vegetables I buy every day,” Fontanive said last summer. “Life won’t be easy during the Games.”

Chef Romano Fontanive, executive chef at the Sol Ipanema Hotel in Río, had to make major changes to his food delivery schedule due to transportation rules changes during the Games. Nevertheless, he was optimistic about the Olympics’ success. “We need good news in this country right now,” he said in July 2016.

HAULING IN THE DARK

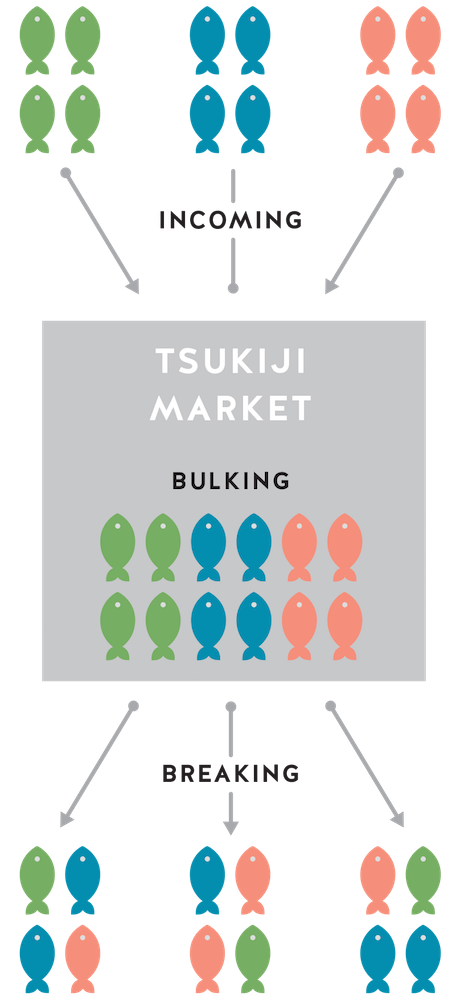

Ceasa is controlled by the state of Rio de Janeiro and works like a giant farmers’ market: food producers rent stalls to show and sell their products in a 20,000-square-foot hangar. There are 800 companies and 2,000 producers registered. Every day, 3,200 trucks pass through Ceasa’s gates. But between July 19 and Sept. 9 (the lead-up to the Olympic Games through the opening of the Paralympics), moving around the city was harder than ever. The plan to reduce traffic for the Olympics forbade trucks from crossing specific areas at different times of day. In Ipanema, for instance, the prohibition was from 6 a.m. to 9 p.m. on weekdays. Many of the vehicles had to wait at the market’s parking lot until the nightly driving window opened when they could drive back to their farms or transport products ordered by customers in the downtown areas. The regulations affected not only Ceasa, but all food providers. Trucks were only able to move freely from midnight to 6 a.m., which means establishments had to keep their employees waiting during non-commercial hours to receive deliveries. The Supermarket Association of Rio said before the Games that the rules wouldn’t affect product offerings in terms of quantity, but it might affect their prices, since the companies could decide to pass the extra costs along to the customer. The Cargo Transport Federation of Rio estimated that 3,000 companies would be strongly impacted, with losses of around 20 percent.

To prepare for the disruptions, the Sol Ipanema Hotel — located at Ipanema Beach, one of Rio’s postcard views — began organizing for the Olympics in the spring of 2016. “Our occupancy rate is high all year, so it’s not hard to adjust our supply,” said Fontanive at the time. But what did change was the amount of perishable food they bought each day. “We are buying more seafood, fish and vegetables to replace what is spoiled during transport” — 20 percent more, Fontanive said. Despite the turbulence with the food supply chain, the chef hoped for the best.

Farther away from Ipanema, going up to Babilônia Hill, one of Rio’s slums, David Bispo seemed less concerned. Bispo is well known in the city after winning several food contests with recipes inspired by the favela’s cuisine, like a mix of seafood with beans. Since the favela was pacified by Rio’s police force in 2010, the Bar do David has become an exotic destination for tourists. Like the Sol Ipanema, Bar do David relies on Ceasa Market as its main food provider. But unlike Chef Fontanive, Bispo wasn’t worried about the food supply during the Olympics, explaining that one has to dance according to the music to make it work. “It’s the jeitinho brasileiro [the Brazilian way of life]: we make it last minute, but we make it work,” Bispo said in July, referring to both his bar and the city’s planning for the Olympics. He decided to wait and see how the first days of the games went before changing his menu or buying more supplies.

JEITINHO BRAZILEIRO

A typically Brazilian method of social navigation where a person may use emotional appeals, family ties, promises, rewards or money to obtain favors or to get an advantage. The expression also comes from the necessity associated with a lack of resources and help. “Jeitinho” comes from the expression dar um jeito, literally, “to find a way.” It implies the use of resources at hand, as well as personal connections and creativity.

One of the largest food markets in all of Latin America, Ceasa covers 7.5 million square feet. Famous for its flower and plant markets, Ceasa serves citizens as well as restaurants and other businesses in Rio. Image by: Luis Barrios

FEEDING CHAMPIONS

Tourists weren’t the only visitors in Rio last summer. Some 11,000 competitors chasing medals descended on the city, and all of them had to be fed, too. Despite early concerns that the Olympic Village wouldn’t be ready for the thousands of athletes, coaches and trainers when the delegations arrived, the restaurants opened for business. In the Olympic Village, Sapore — a São Paulo-based catering firm that managed food in 12 stadiums during the 2014 Rio World Cup — ran five restaurants with a total combined area equivalent to three soccer fields. They served European, American, Asian and Brazilian specialties 24 hours a day, including pizza, salads, hamburgers, several kinds of pasta, Japanese food, cold sandwiches and some typical Brazilian food, like feijoada (a stew of beans with beef and pork) and coxinha (chopped chicken meat, covered in dough, molded into a shape resembling a chicken leg), with meals also prepared according to Jewish and Islamic specifications. More than 250 tons of food was served per day. That included 100,000 loaves of bread and 3,000 pizzas.

One of the requirements of the Brazilian Olympic Committee (COB, in the Portuguese initials) during the bidding for caterers was to use as much local food as possible, starting with food produced in Rio, followed by products from the rest of Brazil, then South America and finally internationally. Sapore didn’t have to go that far. All the ingredients in the Olympic Village were procured from Brazilian farms, except for a species of foliage typical of Korean cuisine that is not produced in large quantities in the country.

Ingredients arrived at Sapore’s kitchen all day. Twenty-five heavy-load sealed vehicles transporting food for the Olympic Village received permission to circulate on a different schedule than the one followed by other trucks in the city. “The truckers working with us have authorization to make the deliveries on time,” said Veridiana Corrêa, Sapore’s executive director for the Olympics, last summer. Before disembarking to the kitchen, however, products were taken to Sapore’s Food Quality Center in Duque de Caxias, a nearby city. A team of specialists checked the products according to rules set by Anvisa (Brazil’s authority on health surveillance) and the International Olympic Committee. The suppliers were instructed to send fruits, meat and vegetables already peeled, chopped and ready to cook as a way to reduce waste and facilitate work in the Olympic Village. There, another team was responsible for a final inspection of the ingredients.

Sapore’s Food Quality Center in Duque de Caxias. Before being delivered in the Olympic Village, the food is inspected here.

Technology helped Sapore’s 2,000 employees working in the operation. Computers monitored the temperature of 345 ovens, refrigerators and freezers 24 hours a day. A cloud-based system used cameras in the dining halls to count how many people were in the restaurant and send the kitchen an estimate of the amount of food needed. A digital spreadsheet with previously collected data also helped the chefs calculate how much food should be bought and prepared, according to the number of athletes in the Olympic Village.

All food served was free to the athletes, who could choose from healthy meals, like light sandwiches and salads, or fast food items — a choice that proved vexing for delegations’ nutritionists during past games. (Some teams, like the Australians, brought suitcases with supplements to ensure their competitors keep their diets on track.) In fact, Corrêa said, during the first days of competition, athletes ate a lot more fast food than the company thought they would. But as more events got underway, “the demand for salads and vegetables began to increase as more and more of them started to compete,” Corrêa said. And once those competitions were over, many athletes tossed their strict training regimens. “We don’t have a number of how much fast food was consumed, but I can tell you this: The swimming teams, specially the American team, can eat burgers as I have never seen someone eat before,” Corrêa said.

“A TASTE OF THE GAMES”

The plan for feeding the athletes was published in a 37-page document called “A Taste of the Games.” When it was created in 2012, one of the COB’s biggest commitments was using organic ingredients in the Olympic Village and the rest of the buildings. The plan was to encourage the catering companies to participate in an organic food supply program, called Rio Sustainable Food, by making that a distinctive factor during the bidding. With enormous quantities of food served in the Olympic buildings, it made sense to use this as an opportunity to help organic farmers, who usually lack a formal education and money to invest in their business, and often suffer from the competition of bigger and non-organic farms. But in the end, only one of four caterers hired by the COB signed up to participate in the program. The impact was negligible: R$4,000 (about $1,200) during the Olympic and Paralympic Games.

Another vow was to minimize food waste. Approximately six tons of produce and other ingredients went uneaten every day in the Olympic Village. But their destination was not the trash. Each day during the Olympic and Paralympic Games, the excess was transported to Refettorio Gastromotiva, a soup kitchen created by the Italian chef Massimo Bottura (the best chef in the world, according to the 2016 World’s 50 Best Restaurants ranking) and social initiatives in Brazil. The items were ingredients that would have been wasted, such as vegetables considered out of the norm for sale in supermarkets: “We are talking about an ugly tomato, an imperfect zucchini, already mature mangos or flour to make bread,” Bottura explained to the BBC. Bottura and his army of volunteer chefs from all over the world served the extra food from the Olympic Village to the poor people of Rio (2.8 percent of the city’s population live on less than one dollar a day, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics). “This is not just a charity; it’s not just about feeding people,” Bottura said in a New York Times article last August. “This is about social inclusion, teaching people about food waste and giving hope to people who have lost all hope.”

Italian Chef Massimo Bottura created the Refettorio Gastromotiva, a large pop-up soup kitchen repurposed food from the Olympic Village into meals for Rio’s poor during the Games. Image by: Angelo Dal Bo

As for Chef Fontanive and David Bispo, they managed to withstand the major logistical hurdles. Bar do David was operating on full capacity during the Olympic Games and the Paralympics. “We had long lines of people at our door on the weekends,” Bispo says. He estimates that the number of clients was up 30 percent during the games. To manage the traffic snarls, he hired two helpers and avoided Ceasa Market altogether. “We decided to buy food in another farmer’s market, farther away,” Bispo says. “It was faster to cross town than to go to Ceasa.”

Fontanive took a different approach. After the first truck regulations were published in mid-July, Fontanive predicted chaos with deliveries. As part of his early planning, he decided to stock all non-perishable items used by the hotel’s restaurant, especially grains and beverages. “I had to reduce my dependence on the delivery trucks,” Fontanive explains. “We had to adapt. It was a very busy time for business, but the city didn’t plan well enough for the business owners.”

LIVING WITH THE LEGACY

“The Olympic Games bring more than the Olympic Games.” The quote, printed on a giant billboard in the middle of Rio de Janeiro in the lead-up to the Games, tried to remind cariocas (the term for Rio natives) why hosting the event would be good for the city. It will leave legacies, it claimed. According to Datafolha Institute, 60 percent of the population was against the Olympics in Rio, because they believed the resources of a country in crisis should be destined to deficient areas like the public health system and schools. During the opening ceremony, though, this pessimism was momentarily forgotten, as the country put on a simple but energetic performance to receive the 207 participating delegations.

But almost six months after the games ended, many of the touted “legacies” are not part of the population’s reality. Many construction projects weren’t finished, and certain plans, like Rio Sustainable Food, weren’t fulfilled. The houses and apartments in the Olympic Village still aren’t being used for social housing programs, as the government planned. Nobody, not even the leaders of those programs, is sure why. The promise of visibility for the city, in the expectation of attracting tourists and investments, also might be compromised with news reports of political corruption, financial crises and violence spreading all over Brazil. Police, firemen and many public employees have not been paid since June 2016, and the unemployment is 11 percent and rising. Even Rio’s other well-known splashy events are being scaled back: the 2016 New Year’s Eve party was the smallest in 10 years because of a budget shortfall.

As of December 2016, food-related expenses of the Olympics were still not quantified by Brazilian Olympic Committee, which is keeping a low profile as the city faces a major economic crisis. Overall, the games are projected to cost $12 billion, with 57 percent paid for by Brazil’s government and 43 percent by sponsors. There were some good outcomes: the 1.6 million tourists that came to the games spent R$424 (USD$125) a day, and international media coverage was largely positive.

“I was so proud of my city and my country,” says Fontanive. “We were facing a huge financial crisis, we still are, but we were able to create a beautiful event for everyone. But it is over and, now we have to deal with tough reality.”

INTERNATIONAL MEAT STANDARDS

For the athletes’ sake, failure was unacceptable in any of the 1.8 million meals provided in the Olympic Village, especially when it came to cooking meat. The main concern was the presence of substances like clenbuterol, used as treatment for breathing-related diseases in cattle. The drug has anabolic effects that can be identified by doping tests — and no athlete wants that. Brazil is one of the few countries that still authorize clenbuterol use in food-producing animals (the Food and Drug Administration banned it in the U.S. in 1991). But Sapore, the catering company chosen to provision the Olympic Village, ensured them the village would be free of the supplement. “All suppliers have certificates attesting a clenbuterol-free diet for the cattle,” said Veridiana Corrêa, Sapore’s executive director for the Olympics.