No Lunch Pass

Not a day goes by when we aren’t told how Big Food conspires to make us fat while exploiting our environment. Is this really the end of our debate about the state of our food system?

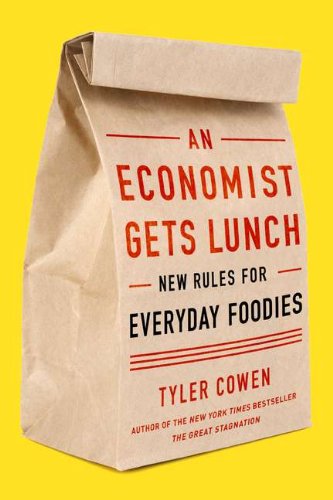

Tyler Cowen’s book, An Economist Gets Lunch (2012), offers an alternative view, one that might spread the blame rather than give us all a pass. He suggests that regulation, television, war, and changing demographics in the 20th century shaped a food system that looks industrial and often tasteless — and in some cases, harmful to our health.

Cowen’s view is this: First, Prohibition in the 1920s put many restaurants out of business, since they relied on revenue from alcohol sales to financially sustain them. Many of the restaurants that went out of business were serving more creative, gastronomic meals to their customers. So culinary innovation left the American food culture with the closure of their restaurants. The restaurants that survived were those who catered to customers who did not drink alcohol with meals and were less discriminating, happy with diners, coffee shops, and less inventive cuisine. (Europe, on the other hand, had no Prohibition Era, so they kept their creative juices flowing, keeping culinary standards high.)

World War II kept culinary standards low with the onslaught of rationing, the disappearance of quality ingredients, and the entry of women in the workforce. Women moved their families to convenience food and stopped creating an American food culture while burying home economics in schools. More preservatives appeared in food as households relied on meals made in advance of the workweek. Long distance supply chains developed to enable more food to travel through a more industrialized system so that Americans could have low-cost, easy to make food while women disappeared from the kitchen. Convenience food arrived. Big Food, as it’s called today, was created by the consumer as the consumer changed, eating habits changed and American food culture stalled.

“Big Food, as it’s called today, was created by the consumer as the consumer changed, eating habits changed and the American food culture stalled.”

Added to this was a move toward nativism during the mid-19th century, depriving American cuisine of the lusty, creative, and diverse favors brought to the table by immigrants. That’s changed now, but in the 1920s and 1930s, restrictions collided with war, Prohibition, and the Depression. And the arrival of television, which, as we know, brought TV dinners, endless gawking at cheesy shows, the demise of family meal times, and the emergence of children as the arbiters of taste. Families, even now, allow kids to determine the food on the table. Usually, that’s not kale and brown rice, salads or vegetables.

Tyler Cowen offers us an opportunity to look in more places for the source of (and solution to) our current predicament. Maybe Big Food is an easy target, but our curiosity can be fed by a more diverse range of topics by diving into American culture, finding how to change our media addiction, being curious about new ingredients and cooking a meal in our own kitchen.