Food Movers: The Secret Evolution of the Pizza Box

No other paper product evokes such hunger. The warm feeling of a pizza box on your lap as you copilot the family car makes anticipation peak for most 10-year-olds.

The mere sight of one — or even better, a stack of boxes — hints at an impending celebration. It may be the only piece of cardboard that makes a mouth water. The pizza box is one of those everyday items that seems ever unchanged, a constant in food transportation. But its technology has quietly evolved while most of us have remained distracted by the pie protected within. Upon closer inspection, the pizza box reveals an unseen story of the sometimes conflicting relationship between a package and the food it contains.

Ordering Out Is In

Although pizza boxes didn’t become mainstream until a decade after World War II, early reports of the use of pizza boxes go back to the 1930s. Prior to that, flat paper bags served as the first transportation vessels for American pizzas, like the paper that wrapped around their Italian counterparts. Back in Italy, a pizza was much smaller than it is in most of the world today — about the size of a tortilla — because it was intended for consumption by a single person. It was a street food consumed by peasants and never needed much in the way of packaging. Pizza’s move to America in the early 20th century, brought by a huge influx in Italian immigrants, greatly expanded the food’s market and led to a need for larger packaging.

The postwar boom of the 1950s convinced many Americans to move from urban areas to the suburbs, where they learned to appreciate the growing convenience-food industry. Frozen TV dinners and Chinese takeout began as a novelty but soon became part of families’ weekly dinner routine. The shape and customizability of pizza made it a perfect addition to the mobile food trend. As pizzeria orders increased, so did the need to stack multiple pies. The solution required ditching the flat paper bag in favor of a more rigid container. Early examples began as modified bakery boxes but came into their own as paperboard pizza boxes. This material, still in use today, is made from compressed paper about as thick as cardstock.

While this design does a decent job of housing the pizza as it travels from point A to point B, it has some shortcomings. First, the printing on these boxes is rather simplistic and inaccurate. Printer rollers don’t get much cushioning from thin paperboard, so ink tends to smudge. Second, and functionally more important, the box’s walls tend to buckle and gap, even without a pizza inside. Just imagine what happens when the box is loaded with a hot, steaming pie. Add to that the lack of structural integrity inherent in thin paperboard: It doesn’t take much weight to collapse the lid, pushing it into direct contact with the pizza itself. (You’ve probably seen those tiny, white plastic “dollhouse tables” inside the box — that’s the Package Saver, invented by Long Islander Carmela Vitale in the mid-1980s. The box wasn’t good enough on its own; it needed some support to get the job done.)

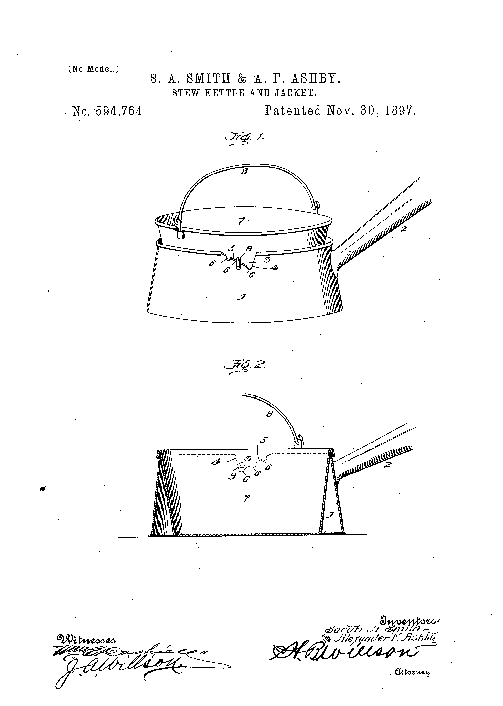

THE PACKAGE SAVER

was invented and patented by Carmela Vitale, whose device has saved the molten toppings of countless pizzas since 1985.

The GreenBox

It might look like a standard corrugated pizza box, but the GreenBox is designed to break down for two secondary uses. The lid has a pair of crossed perforations that allow it to transform into four plates. When you’ve had your fill, the base folds over itself to create a low-profile take-out container for your leftovers.

Corrugation Nation

By the late 1960s, the American pizza industry shifted from urban Italian communities to the suburbs. That meant more pizza being made for more customers — and most of it was being delivered. But the paper industry was slow to respond to demands for a stronger container. It took a little company from Michigan called Dominos to convince their box supplier to develop a product made of corrugated paper.

In his autobiography, “Pizza Tiger,” Domino’s founder Tom Monaghan writes about developing a corrugated pizza container with a Detroit-based company called Triad. Corrugated paper is composed of a flat liner and a fluted medium. The latter is a wavy sheet of paper affixed to the flat liner with food-safe glue. Besides enhanced strength, corrugation also enhances insulation to keep the pizza hotter longer.

The Modern Box

The result is the box you know best — it’s thicker and stronger than its paperboard predecessor and always need the little plastic dollhouse table. As a bonus, images print more sharply on corrugated than on paperboard because the corrugation provides cushioning for the printing rolls.

Alas, the trouble with insulation is that it leads to soggy crust. The steam that keeps the pizza hot leads to its downfall. The sad truth is that most consumers have grown accustomed to this tradeoff — but that doesn’t stop inventors from trying to solve the problem. One novel approach enables the offending steam to escape. A corrugated paper company in India called Shree Krishna Packaging invented Ventit, a box with indirect ports that exhaust steam without losing heat. At trade shows, the company demonstrates its ingenious design by holding a lit incense stick inside the box. Viewers can see the smoke exit the box without the implementation of direct ports.

In a 2007 study, the Institute of Chemical Technology in Mumbai confirmed the company’s claims that their design keeps food contents hotter than standard boxes. Blind taste tests by pizzeria customers back up these laboratory claims. But despite expressed consumer preferences for a box that would deliver the best pizza — even for a few more cents per box — food distributors are wary of the extra cost.

Ventit’s Breathing Pizza Box

Pizza boxes have always fought a battle between retaining heat and evicting moisture. This innovation uses indirect venting through the flutes of corrugated board to allow steam to escape while retaining more heat than the common pizza box. It’s currently available only in India and Dubai, but more smart pizza companies are bound to catch on.

The Table Box

Leaving a pizza box on the kitchen table means losing valuable surface area — until now. The lid of the Table Box flips beneath the container and transforms the box base into a pedestal. With your pizza elevated six inches above the table, you have plenty of room for cups of pepper flakes, oregano and grated cheese.

B Flat

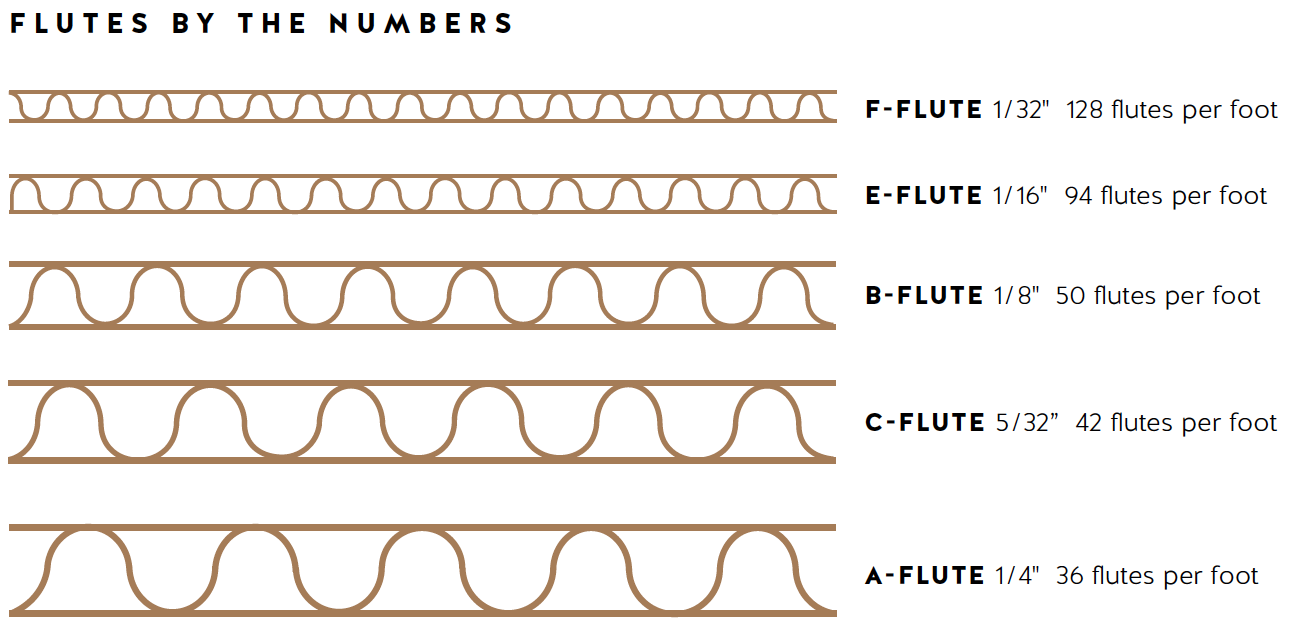

Old school pizzerias, particularly those in the northeastern U.S., tend to avoid change in fear of damaging their legacy. Corrugated pizza boxes are composed of a pair of flat paper liners sandwiching a wavy paper layer. The resulting peaks and valleys — or flutes — determine a box’s thickness and strength. Flutes are labeled with letters that correspond to the order in which they were brought to market and also happens to match their thickness in descending order.

“B flute” boxes are the most common in New York pizzerias, but newer “E flute” boxes are thinner and cost less to ship. They even print better than thicker “B flute” boxes because their flutes are closer together, providing a more even surface. Even with all these advantages, most pizzerias in the New York area are stuck on B.

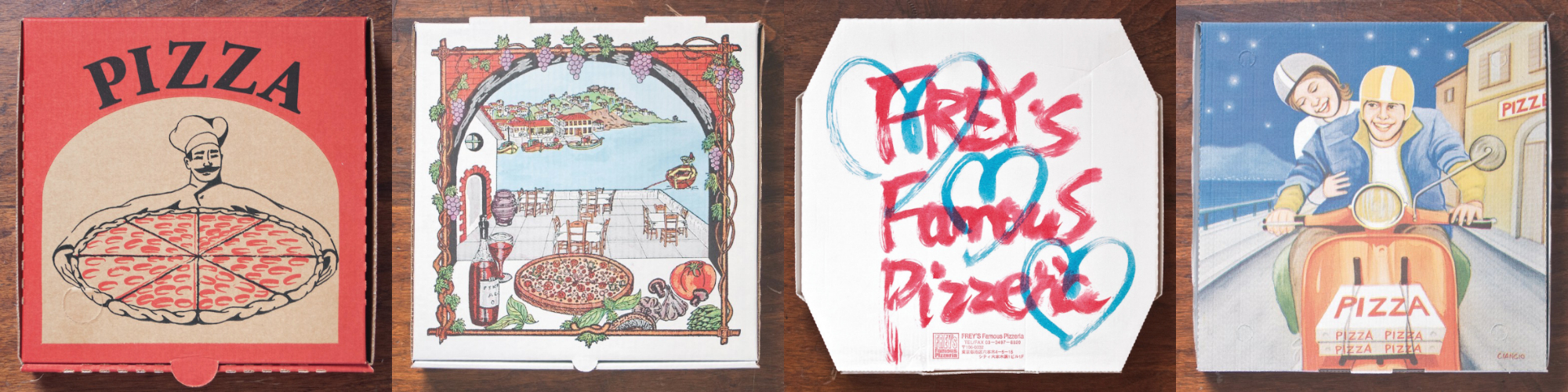

Such is not the case in Italy, a place known for design that integrates art and technology. Although they’ve had pizza much longer than their American counterparts, the Italians have only recently adopted the practice of take-out and delivery. With a younger pizza box industry, Italian pizza box makers have newer equipment that enables more detailed printing. Their pizzas are also smaller and less hefty than their American cousins, alleviating the need for thick boxes.

This combination of thinner boxes and newer equipment has led to an explosion of beautiful artwork on pizza box lids in Italy. They look more like paintings than disposable food containers. It’s worth noting that these treasures reach the hand of the consumer after a purchase has been made, so the art comes as a surprise, rather than a tool for marketing.

Pizza boxes have long been a silent aspect of the pizza buying experience. We tend to overlook the box, relegating it to the dumpster as soon as the last slice disappears. All the while, innovators plug away at solutions to problems most of us don’t even realize exist. Only recently are consumers waking up to the fact that the vessel can be just as important at the food it holds.

The Pizza Pod

Zume Pizza, a startup in Mountain View, Calif., has created the pizza box of the future. Their entire concept is futuristic, starting with the use of robots to make the pizza rather than temperamental humans. It only makes sense that they invented a pizza box to match. Dubbed the “Pizza Pod,” this odd container is made of compressed sugarcane fiber. It absorbs moisture, leaving the pizza dry and crispy. The shells are also completely biodegradable.

For more images from Scott Wiener’s collection of more than 1,300 pizza boxes, get his book, “Viva La Pizza.”

What brain-tickling books, podcasts, movies or YouTube channels are you enjoying right now? Tweet us

What brain-tickling books, podcasts, movies or YouTube channels are you enjoying right now? Tweet us

DELI MAN

DELI MAN

Clover

Clover

GASTROPOD; 99 PERCENT INVISIBLE

GASTROPOD; 99 PERCENT INVISIBLE