by Food+City | Jun 17, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

June 13th – Day One

Am setting off to track the ingredients of food items made in cities around the world. The purpose is to better understand how cities are fed, mapping out the movements of ingredients from the origin of raw materials to the plate of the consumer. So, starting in Paris, with a simple ham and cheese baguette.

Slept all the way through the 10+hour flight to Munich and then on to Paris, arriving during a one-day taxi strike on a rainy day. Am staying in a small hotel, Hotel Verneuil, located on a quiet street on the Left Bank St. Germain des Pré district. After a quick shower, a strong espresso from the cozy, wood-paneled lobby, I headed off to meet Lauren Shields, my researcher who has been soldiering on through her list of contacts to set up appointments for me during my visit.

Lauren is an American, born in Montana, studying international food policy at a French university. She graduated a few weeks ago and is now on the hunt for a job somewhere in the European food policy universe. She met me for tea at the Comptoir des Pères, where we talked about our plans for the next few days as I sipped a tisane and she a “noisette,” an espresso with a small pitcher of hot milk on the side. We talked for two hours, and developed a list of ideas, places to visit, and some questions. Such as, “Why don’t Parisians talk about locally food? Perhaps it’s because they think of all of France as their backyard, and thus all food produced in France as local.

June 14th – Market Day

Tumbled out of the hotel at 4:30am for a tour of Rungis Market, one of the largest wholesale food markets in the world located southwest of Paris. As the sun rose, we entered the Fish Hall, lights glaring, floor shimmering wet, and white Styrofoam boxes for the length of the icy-cool space. A display market, meaning that buyers and sellers see the fish, touch the merchandise, and settle on prices rather than purchase catches through an online auction system such as buyers in Boston. During the 1960s, Rungis replaced the famous and historic Les Halles market in central Paris, the site of Emile Zola’s novel The Belly of Paris.

The only way to officially see the market is to join tour or be a buyer. I joined a tour and was stunned (difficult at 4:30am) to find a large tour bus packed with tourists from all over the world who rallied early and paid to see a wholesale food market. Would anyone in New York get up at 5am and get in a tour bus to visit Hunters Point? Doubt it, but that might change.

We spent five hours walking through buildings that contained fish, beef, chickens, offal, vegetables, fruit, cheese, and more, much of which was contained in 40-degree Fahrenheit temperatures. The market is so big that the tour buses drive from one building to another, winding through trucks and forklifts that are trying to get business done before the market closes. And our group, like all the other touring groups, wandered wearing the required hairnet and white coats, making us look like clueless inspectors, pointing and asking questions that the vendors had answered at least a dozen times that morning.

The professionals in the market did not seemed annoyed with us, as we blocked traffic, got in the way of carts moving produce out onto waiting delivery trucks, and pointed cameras into the boxes of fish, meat, and chickens. The star attractions included the chickens with their heads looped around their carcasses, large bloodied beef hanging along with a photo of the animals when they were alive, tranquilly grazing in their home pasture, cases of foie gras, and piles of detached pigs feet, stomachs, and calves brains. Pretty tough going for a pre-breakfast visit.

In spite of all the fresh and glory food, the halls were amazingly clean, stainless steel gleaming, and floors immaculate with the exception of a few drops of blood left by those animals hanging unsold by the end of the market day.

More details of the market will be forthcoming, but to give you a flavor of the morning visit, here are some samples of what awaits you should you decide to become a wholesale market tourist in Paris.

June 15th – Say Cheese

Sounds simple, yet Parisians just can’t tell us what kind of cheese they use to make their traditional “jambon/fromage,” or baguette with ham and cheese sandwich. I’ve been asking Parisians now for almost a week and each person declares with absolute conviction that the cheese is Emmanthal. No, actually, it’s Gruyere. Oh, wait. It’s Comte cheese.

The ham is another story, but one that exacts almost a sense of apathy, which for a Parisian seems out of character. The ham used for the sandwich is sometimes call Jambon de Paris, or Parisian ham, but is really just a simple boiled ham, not tied to any location or terrior, which in other cases is the Parisian claim to culinary authenticity.

Same for the bread. The baguette has no geographical identity, other than all of France, and comes in various combinations of flours. The only exactitude required is the government regulation for the combination of ingredients: flour, water, salt. The French state has had its hands in bread at least since Louis XV (1710-1774).

The temperamental French view of the cheese in their iconic sandwich led me down some blind alleys. Such as one at the end of a trip to the Jura, Comte region south of Paris to investigate the source of Comte cheese. The tour guide of the Comte cheese center proclaimed the excellence the forty-pound rounds of gruyere-like cheese, including the astounding fact that only one breed of dairy cow is allowed to make the cheese, the Montbéliarde. The cheese, while creamy and, depending upon its age, nutty, turns out not to be the cheese of choice for the “jambon/fromage.”

Two days later, the consensus is that it is Emmental, a Swiss cheese, is the traditional cheese eaten by most Parisians in this sandwich. For now, am running with the holy cheese, finding what French company is making the Swiss cheese for the French sandwich.

June 17th

The Sandwich: Jambon/Fromage

Tracking down a sandwich is my mission, this one in Paris, and made by the Martin family in the 10th arrondissement. By tracking down the ingredients for one sandwich, made by one shop, makes the task of understanding how Paris gets fed manageable, although still confusing and complicated. Ingredients for one food item at one location often change from one day to another; bakers buy their yeast from the best supplier at the most reasonable cost, for example.

The vagaries of supply chain dynamics means that you can’t track down all ingredients for all sandwiches made by one baker, but simply one made at one time on one day. Thus the challenge. And the opportunity.

So the tracking began today and thankfully, our bakers were all in, happy to share their shop, ovens, and interest in the adventure. They hauled out flour sacks, tubs of salt and yeast, and labels from packaged ham and cheese. Yes, Emmental. Next step: find those supply chain delivery trucks, the ham processor, cheesemaker, and yes, the cows and pigs.

by Food+City | Jun 8, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

My last post about the early years of food on TV brought back memories of those days of easy pleasures created by the mere presence of a TV in your home. In our house, the small black and white television sat near the kitchen and after school we gathered round to watch Engineer Bill drink milk in between cartoons that he ran with his program, Cartoon Express.

William Stulla, AKA, Engineer Bill, began his program in 1954 and rolled into living rooms at 6:30 in Southern California, when I was six years old. Our family wouldn’t miss a night.

For a few minutes every evening, around the dinner hour, he would appear in his railroad engineer garb clutching a glass of milk and challenge us to gather around the TV with our own full glasses of milk. He would announce the start of his game, Red Light, Green Light, a game that entailed drinking milk whenever “Freight Train” (his off-set announcer producer) shouted “green light.” Every few seconds he’d shout Red Light or Green Pants or some other feinting ploy to fool us into drinking at the wrong time.

Families like ours were gathered around our small sets, giggling and gulping all the while in an effort to finish our glasses of milk before we mistakenly drank at the wrong time. This required us to be riveted to the TV. Engineer Bill played with us and for those of us who succeeded in downing all of our milk, he’d ring a bright bell and for those of us who stood grasping a glass still full of milk, he rang the “lead bell.”

This was a time of cleaning one’s plate, drinking your milk, “building bodies 12 ways”, as the bag of Wonder Bread claimed.

The game was fun and apparently we must of gulped down gallons of milk over the years of our early childhood, me and my two brothers.

But wait, what if we replicated this program today, gathering around the TV, clutching bags of freshly picked green kale or a probiotic yogurt smoothie. Would the tactic work? Would this be our modern gamification of good eating habits? Could we engineer a new generation of vegetarians or even vegans? Or, would our children see through the thin veneer of good intentions? Would adults accuse the milk lobby of victimizing our children? Or would the competitive nature of the game put off those who are revolted by the ideas of winners and losers?

Still, maybe an opportunity to find a motivator for our younger generation to develop good eating habits. (Although gulping might not work.) Instead of wishing our children to eat kale because it’s “sustainable” and good for our planet, perhaps we could fast track their healthy diets by a new engineer, one that builds software, and introduce a game that counts towards building a generation of healthy kids.

Skip to minute seven in this video to catch a clip of the Red Light, Green Light game. https://youtu.be/GzvdlE45XEI

by Food+City | May 31, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, History, Stories

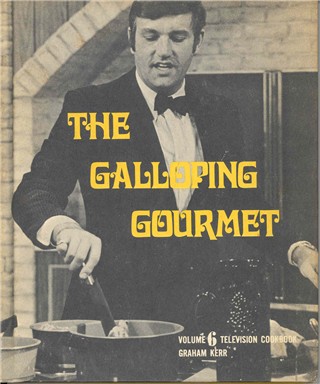

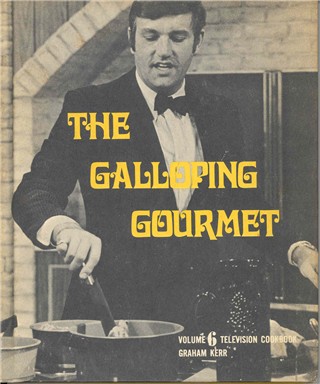

Graham Kerr. The Galloping Gourmet. The man and his brand are inseparable for most of us who got a taste of food programs on TV during the 1960s. Mr. Kerr first appeared on what was known as “experimental TV” on April 16, 1960, before the acclaimed Julia Child made her debut as The French Chef in 1963. But even before the two appeared on TV, Marcel Boulestin, a French chef living in England, appeared on the experimental television programs produced by the BBC during the 1930s. In January 1937, Boulestin demonstrated how to make an omelet for his first program called “Cook’s Night Out.”

Experimentation defined the 1960s, and television was no exception. Early television stations were called “experimental” from the 1920s through the 1950s when broadcast frequencies were not yet commercialized or available to the general public. The BBC’s 1937 program guide reads like a listing of experiments interspersed with articles touting the latest developments in broadcasting technology.

Far from experimental was the decision by both Boulestin and Kerr to begin their programs with an omelet. I asked Kerr why an omelet was the star attraction for his own television debut. He suggested that it was a dish that most viewed as complicated but that, with simple instruction, would enable viewers to achieve a quick victory in their own kitchens.

Watching an omelet take shape during these early years, those who could afford the new Marconi-EMI televisions required good eyesight. The TV had a screen size of only five to eight inches, miniscule compared to our high-definition 152-inch screens.

Why was food one of the first topics to appear through this experimental medium? It may be that the broadcast spectrum became a means for popularizing culinary skills as a way for consumers to save money. Before the WWII, middle class families often left culinary skills to their own chefs or ate at restaurants. The names of the early broadcast programs reflected the idea that a housewife prepared a good meal when her household staff took the night off. And before the war, during the 1920s, books and radio broadcasts included programs that suggested ideas for saving money, such as one program in 1927 called “Wastage in the Kitchen.”

These early years in broadcast are full of experimentation and enthusiasm. Mr. Selfridge, and American entrepreneur who brought Selfridges department stores to England (first one opened in 1909) the focus of a new Masterpiece Theater program currently running on PBS. Henry Gordon Selfridge introduced the first televisions in his department stores in 1927 with John Logie Baird, a Scottish inventor who is often called the “father of television.” Selfridge, an innovative impresario, was much like Graham Kerr, who began his television programs by running through the audience and vaulting over a couch. His wife, Treena, brought her experience in London theaters and pantomimes to choreograph Kerr’s kitchen presence on TV.

These early entrepreneurs, Boulestin, Kerr, and Selfridge should inspire us to think beyond our contemporary food programs and find new ways to popularize culinary skills and good food. Some early efforts are appearing on website and through software applications. But it will be the sparkling personalities and creativity that will engage us anew, much in the way of Julia Child and Graham Kerr.

by Food+City | Apr 23, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

Just returned from a three-day feast of ideas in Monterey, California at the seventh EG Conference (http://www.the-eg.com/). The annual gathering brings together individuals from media, technology, entertainment — and his year, education. This was my second year attending the event, intrigued by the entirely eclectic group of presenters.

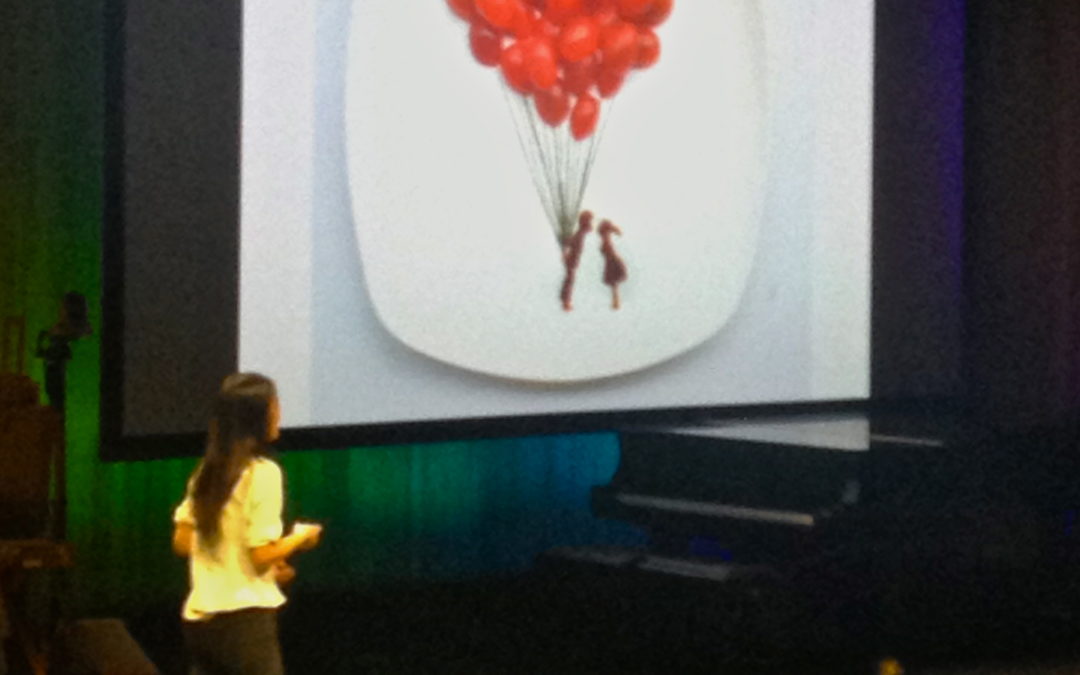

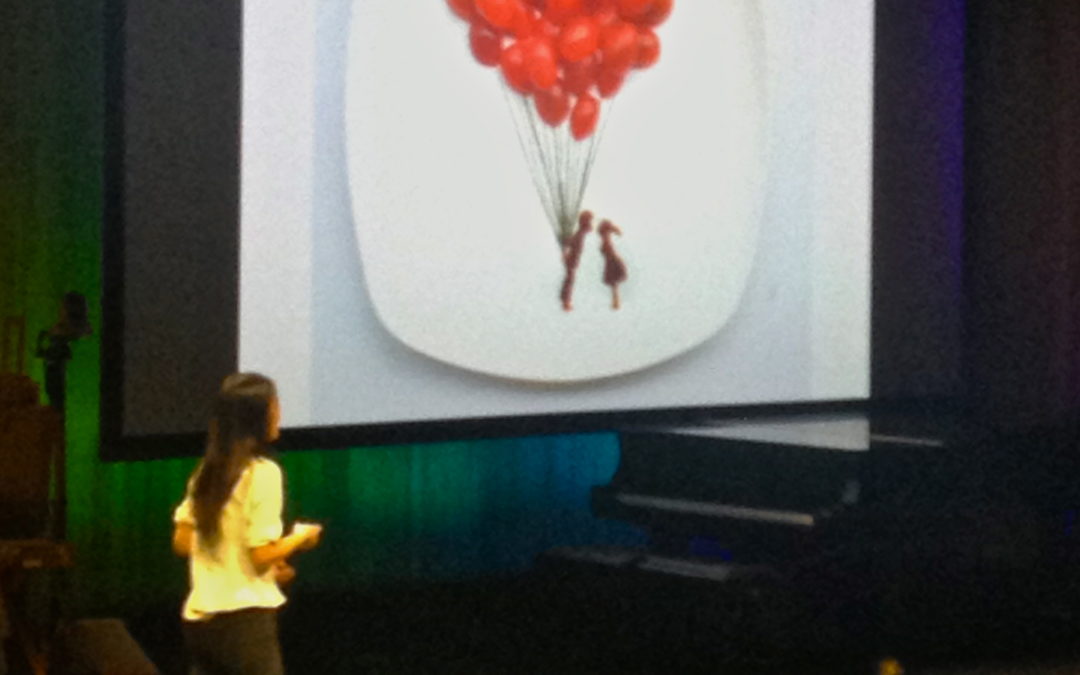

Magicians, musicians, jugglers, and acrobats, astronauts, nature photographers, pick pockets, and art forgers, gathered to explore new ways of thinking about education. With this gathering of intellectual explorers, we heard presentations that revealed a yearning to keep the human connection in sight while reaching to the outer edges of our digital experience. In one section called “Sustenance,” we heard about food as one of those connectors. “Red” (aka Hong Yi) an architect from Shanghai, plated art — literally created art using food on plates that represented “food painting” of maps and more.

Christopher Shi, a gastroenterologist and pianist, persuaded us that digestion of ideas through artistic expression such as music (which he demonstrated by eloquently playing the piano for us) bore similarities to biological digestion. Well, maybe. And Christopher Young, Nathan Myhrvold’s co-author for The Modernist Cuisine, explained life as a scientific chef, inventing experimental kitchens, food, and now his new website, ChefSteps (http://www.chefsteps.com/), where you can find Salmon 104, which describes cooking salmon at the temperature of 104 degrees Fahrenheit.

EG, impresario Mike Hawley’s conference, provoked us to think about the relationship between art and science. As more artists (and let’s include cooks as artists) connect with scientists, we’ll get a new food system that integrates bits with bites, allowing the human spirit to simmer along with the structures of programming and networks. Let’s hope that we hear more about this integration. Congratulations to Mr. Hawley and all the presenters at the 7th EG Conference this year — A mighty meal with much to digest between now and the next EG gathering.

by Food+City | Apr 1, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, Future, History, Stories

Some things are best left unsaid, and my experience as a pig cloner comes up in conversations only to cause nervous twitching on the part of my listeners. “How”, they wonder, “could someone dedicated to conservation and the environment wander off into the black art of biotechnology?”

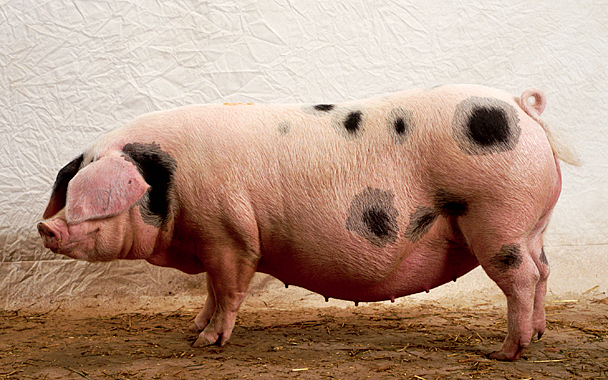

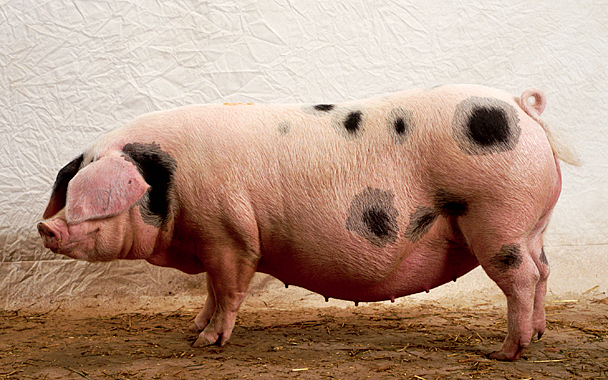

During the years when I was raising heritage breeds of livestock in Maine, I found that one of our precious swine bloodlines was drying up. The farm, founded for the purpose of conserving rare breeds of livestock, operated on the rocky ledge of limited gene material for these minute breed populations. Our pigs, which came from England, had a gene pool consisting of four bloodlines and we had one sow from one of the four lines. She hadn’t had a litter in several years, despite repeated attempts at breeding, coaxing, and the normal veterinary treatments. Genetic diversity for our U.S. herd of Gloucester Old Spots pigs looked prematurely bleak.

Most of us attracted to farming on a large scale come to it with a desire for connection to the earth as an antidote the digitization of modern culture. So the idea of using technology to solve a problem related to animal conservation seemed crazily contradictory for a hands-on farmer.

The seeming contradiction began with a question. What if cloning technology could enable this pig to start all over again? Could we bootstrap her bloodline if a copy of her was able to breed? Might her problems be related to her, not her genetic makeup?

In 2000, Scientific American ran an article, “Cloning Noah’s Ark” and suggested that biotechnology could preserve genetic diversity for animals, which I assumed included domestic animals, such as dogs.

And so did most people. The first customers for laboratories that did cloning were pet lovers who longed for their family dog after the pet’s demise. Cats and dogs were rushed to these labs to reacquire Fido or Fluffy.

But what about a 350-pound hog? At our farm, the staff gathered for a contentious meeting and decision to try cloning to see if a new “copy” of our pig would breed naturally and restart the bloodline. Overcome with moral outrage, some staff quit, others walked gingerly on, but most of us came together with the desire to remain on mission.

Which included the humane treatment of animals. We learned that our sow only needed to have cells gathered from her ear, a process that could cause minimal discomfort. After the skin cells are collected, they are injected into the another sow’s eggs after the recipient’s chromosomes and polar bodies are removed. Once the injected egg contains the skin cells from our pig, an electric shock fuses the skin cell with the egg cytoplasm. The nucleus from our pig cells enters the cytoplasm, fuses, and begins to divide, yielding the development of an embryo. The “fertilized” embryo is injected into a surrogate sow who gives birth to the clone.

We learned about omnipotent cells and conducted a cloning workshop at the farm, offering hands-on experience to the willing and curious. Visitors to the farm explored nuclei and chromosomes under microscopes, winding their minds around complex ideas of ethics and biodiversity.

One of the new cloning companies in 2001 partnered with our farm to explore cloning livestock for conservation, a welcome diversion from Fido and Fluffy. Our sow, Princess, became the proud mother of two piglets, sort of, in April 2002, aptly named Xerox and D’NA. The spots on these pigs were different than those on Princess, providing a lesson in genetic transmission.

The company, Infigen, pioneered the application of cloning technology to breed conservation and was pleased, and so were we as Princess’ offspring went off to produce strapping piglets from her bloodline in subsequent natural breedings.

The uses of such technology can be problematic for the food and agriculture entrepreneurs. GMO technology, for example, taunts those who distrust the aims of technology while beckons to those who see technology as a tool when thoughtfully utilized can break through the limitations of our natural world.

Which shall it be? Could the solutions for feeding our future populations rest somewhere between Princess and the pea?

by Food+City | Mar 5, 2013 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

I recently visited the new exhibit at The American Museum of Natural History in New York called Our Global Kitchen, Food, Nature, Culture. As more and more Americans learn about their food, they can now feast on a museum exhibit that attempts to tell the whole story.

To tackle food as a broad subject is to launch upon a vast ocean in a small barque amidst thousands of hidden reefs. Topics such as genetic modification of foods lurk beneath the surface of most conversations about food. But this exhibit manages to stay afloat, informing visitors without sinking into political or cultural debates. You can wander through displays that explain how humans have shaped food through plant and animal breeding and how food is exchanged through complex trading networks. The exhibit employs statistics and charts, in excess at times, to provide enough information for visitors to come to their own conclusions about the state of our food system.

One display celebrates all the ways that food connects the human family while innovating different tools and cuisines. You can experiment with your own sense of taste by visiting the exhibit’s food science laboratory where you can learn how we sense taste and flavor. One room contains examples of what people ate during different time periods, such as Ancient Rome and Early America. The exhibit curators provided a creative way to tell those stories, using models of what cuisines looked like in their own cultural settings. In all, Our Global Kitchen, is well worth a visit. My only lament is that the exhibit doesn’t come with a printed catalog in addition to a website.

Our Global Kitchen (http://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/current-exhibitions/our-global-kitchen-food-nature-culture), is open until August 11, 2013.