by Food+City | Nov 3, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

Michael Pollan recently spoke to a packed house here in Austin, Texas. The audience included members of “The Food Movement,” as Pollan called them, as well as his many loyal readers. His message was simple, direct, and eloquent. Eat simply, know where your food comes from and ….. beware of capitalism.

Six years ago, I attended a talk by Mr. Pollan in a small Cambridge, MA bookstore when his now award-winning book came out, The Omnivore’s Dilemma. The audience was about a tenth of the size of last night’s crowd and much less enthralled. His talk was just one in a series of authors who stopped by to promote their latest books. Pollan was impressive from the standpoint that he was as articulate in person as he was in his book and he seemed reasonable. Reasonableness is not always a quality shared by those in “The Food Movement” (in which I’ve held sporatic memberships).

Pollan follows the method championed by George Plimpton of The Paris Review: Get out in the field, literally, and experience your topic. His reasonableness arrives through his on-the-ground experience. One of his most famous was his travels with a steer who eventually became his hamburger. Pretty gutsy.

For the past six years, Pollan has convinced thousands of readers of the importance of good food and of our broken food system. But when asked by the articulate Addie Broyles, his interviewer for the evening last night, for his ideas about the future, he seemed circumspect. His early prescient call for alertness about the food we eat could turn now to some unreasonable leadership, the kind that crosses the boundaries between agribusinesses and local farmers. How to create that edgy leadership without losing his following … is the real dilemma.

by Food+City | Oct 28, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

In.gredients, a new Austin food startup, promises to change the way we shop for food. When the company’s founders announced its plan to eliminate wasteful packaging, foodies and the media celebrated the merits of the new enterprise, hopeful that in.gredients customers would arrive at the new store with reusable and recycled bags and containers. The founders announced they would provide package-free food that would begin the march towards a zero-waste food system. Major media outlets such as The New York Times and CNN piled on with accolades for the company, long before the business opened its doors.

Now that the doors are wide open, the company’s big vision seems smaller than advertised. While the beautiful repurposed Austin cottage sells some of Austin’s finest artisanal and local food (bread from Easy Tiger, quiches from Cake & Spoon), the building only contains three rows of bulk bins, hardly half of the bulk bin space in Central Market. After purchasing half a dozen eggs (egg cartons provided) and some peanut butter (plastic tubs provide), I left the store wishing that the founders would begin negotiations with one of the empty warehouses on the fringes of East Austin. In.gredients should return to and embrace that original mission to think bigger and bolder.

If you want to disrupt the food system by building a zero-waste outlet, you need lots of bulk, in the sort of space occupied by Home Depot or Costo. Maybe a package-less Costco, filled with local, healthy bulk food items. Disruptions require boldness, audacity, and the willingness to go all-in with an idea that could overwhelm the package-intensive weak areas of our food system.

The founders of in.gredients are probably not in negotiations with the owners of a large warehouse but they could be inspired by some early examples of bulk food storage that defy the unattractive optics of industrial warehouses, such as the King’s Cross grain depot in London during the 19th century.

London’s grain supply entered the City through rail depots positioned around the periphery, bringing food in bulk from all directions outside London. The train from northern England delivered grain into the King’s Cross rail terminus where Lewis Cubitt built a wheat storage facility in 1851-2. Trains rumbled down from Lincolnshire after the annual wheat harvest, supplied the grain depot at the King’s Cross rail terminus, and departed for London bakeries aboard urban canal boats. Up to 60,000 sacks of grain moved from rail to canal and to the roads in London, lifted up and moved from one conveyance to another by an impressive hydraulic lifting system, a modern innovation of the Victorian period. Acting like our modern “food hubs,” these 19th century bulk food storage buildings appeared in other European cities.

(You can learn more about granaries here: http://www.buildingconservation.com/articles/granaries/granaries.htm) Seems that the founders of in.gredients could find inspiring structures from these early granaries. Founders, Lane brothers, Christian, Joseph, Patrick, and Brian Nunnery, Christopher Pepe.

UPDATE: As of 2018, in.gredients is permanently closed. Read more about the closing here: https://www.austinchronicle.com/daily/food/2018-04-25/damn-it-all-in-gredients-is-closing/

by Food+City | Oct 14, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

During my food history class last week, I showed a video of Martha Stewart visiting our farm in Maine. The students were learning about the Agricultural Revolution in Britain. Late 18th century livestock improvers, such as Robert Bakewell, produced what we now call heritage breeds of livestock, such as Cotswold sheep and Gloucester Old Spots pigs. In 1994, I founded Kelmscott Rare Breeds Farm for the purpose of conserving these old-fashioned livestock breeds. Apparently this endeavor piqued Martha’s interest.

As I watched the video with the class, I saw the students smile, beaming with bright, in-the-moment expressions of delight. Some were laughing at the rambunctious sheep and pigs; others were awestruck by our one-ton draft horse named Pete. Their faces reminded me of how magical time this farm experience had been for both my family and myself. We lived on top of a hill on a farm in mid-coast Maine surrounded by expansive views and pastures inhabited by sheep, cattle, pigs, chickens, turkeys, and those indomitable draft horses. I had forgotten, but my students reminded me, of how those days were so full of beauty and intensity, of earthiness and excitement.

My students watched as I introduced Martha to the animals on the farm, chatting on camera about their histories and the importance of their continued presence on farms today. Visitors to the farm strolled through the barns, touched their first sheep, stood in awe as our border collie, Tess, scurried around the sheep to bring into the pasture. I also noticed how visitors, farm staff, and the students in this classroom now never lost their bright and curious smiles. During the time it took to show the video, all of us in that room were in the fields and barns, smelling the sweet hay in the loft, feeling the energy of life on a thriving farm on the coast of Maine. Perhaps we owe Martha a word of thanks for bringing us back to those days in Maine, stunningly bright and full of hope.

You can see the video here: http://www.marthastewart.com/926681/endangered-farm-animals-kelmscott-farms

by Food+City | Oct 10, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

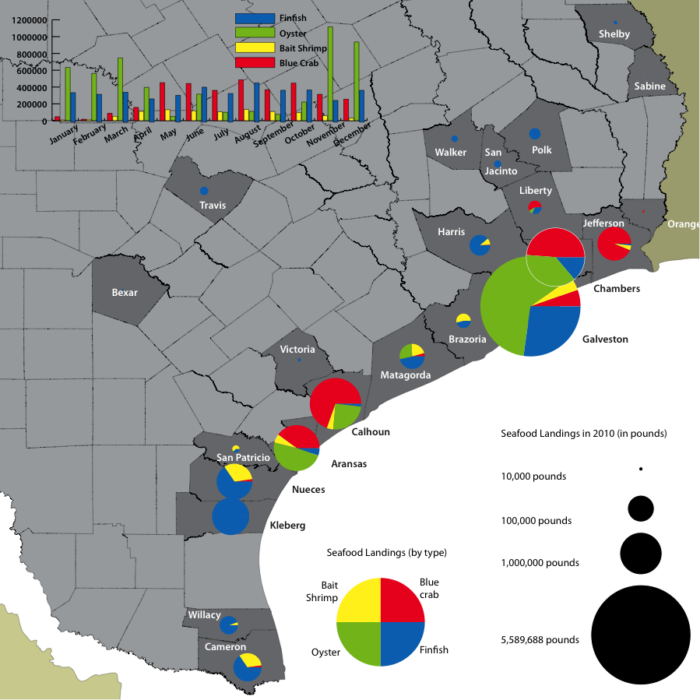

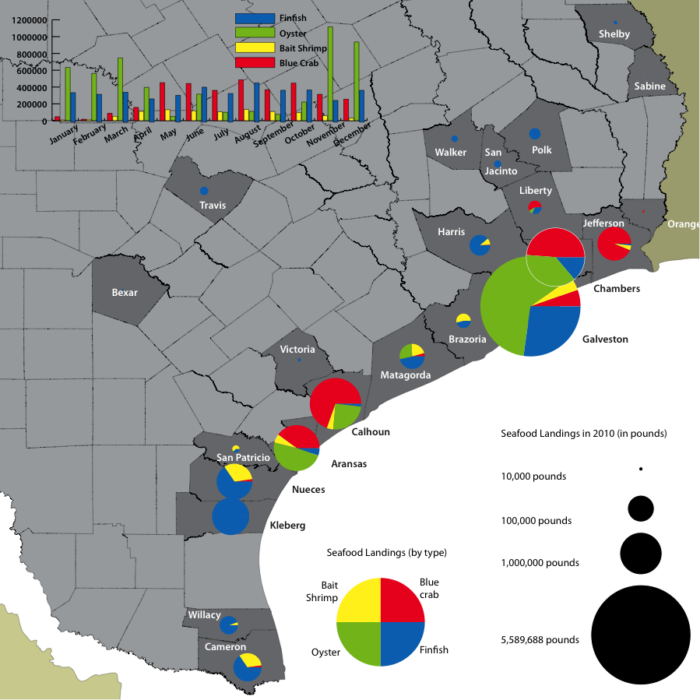

I’ve been working on a food-mapping project for the past several months called Food: An Atlas. The project is a non-profit venture launched by the CAGE (Cartography and GIS Education) Lab at the University of California at Berkeley. The project team intends to self-publish a map created by a network of content providers and cartographers over the web. The idea behind the project is to produce a food atlas in a short amount of time from a broad community of researchers. The Berkeley team, located in the Geography Department, received over 80 map submissions from 10 states in the U.S., South America, and Europe.

Content providers, like myself, provided map data; the project team provided me a cartographer, who happened to be the talented Jeff Ingebritson, a graduate student from the Geography Department at the University of Wisconsin. Together we hashed through my data and his GIS program to create a map of seafood provisioning in Texas.

This was so much fun and an incredibly cool platform. And, I learned what most data mappers already know: You look for data first, then map it. At first, I wanted our map to show how seafood enters Austin, Texas only to find that there is no data for that story. So, I used existing databases and found ways to tell a different story.

The CAGE team plans to publish the atlas online, funded by support acquired through a Kickstarter campaign. See here to add your support HERE.

by Food+City | Oct 5, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

Texas peaches will soon disappear from the Hill Country roadside stands, removing star performers on local restaurant menus such as Peach Melba. Named after an Australian opera singer, Peach Melba was the invention of Auguste Escoffier, a nineteenth century entrepreneur who introduced the ice cream and peach dessert to the Paris Ritz. Demonstrating his creative culinary imagination, he convinced farmers in the Rhone Valley to grow thin-stalked, green asparagus for the British who paled at the white, stocky asparagus on the Continent.

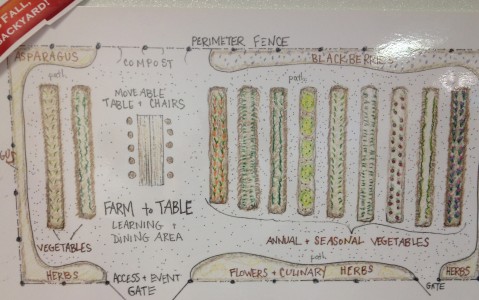

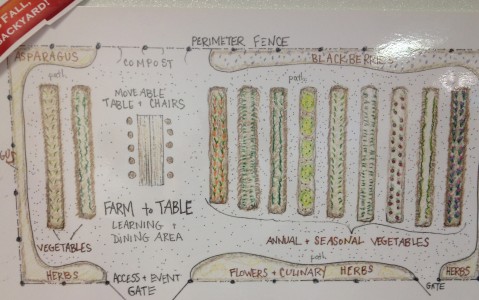

Escoffier’s innovative spirit was evident this week at the Escoffier School of Culinary Arts in Austin where a new Agricultural Learning Center drew the attention of Austin’s food community. Making the connection between food preparation and food production, the school’s new farm-to-table venture will launch culinary students out from the kitchen and into the garden as they learn how to connect what’s in the ground to what’s on their plates. The school is part of a larger movement in food education to connect growing food to making and eating food. Auguste would be delighted, as will be the employers of the new Escoffier graduates. To learn more about the school’s new project, visit http://www.escoffier.edu/.

by Food+City | Oct 1, 2012 | Food Tracks Blog, Stories

My students have just read about the bread riots in France leading to the French Revolution in 1789. My course is about the history of food in Europe and we explore the ways food connects with change over time. Lots of change begins with a revolution. While we were reading about the women who flung loaves of bread at the king in Versailles, the faces of angry men in Cairo were raging over the price of grain as the Arab Spring portended a new revolution.

Egypt, like other countries in its region, feels the effects of declining grain stocks all over the world. Since the Middle East and North Africa depend so much on imported food, drought and the use of grain for biofuels in places like the U.S. and Russia cause price spikes that ignite protest. Wheat and corn futures are up over 40 percent and the U.S. diverts about 40 percent to the production of fuel for cars.

The women in Versailles demanded that the king find a solution to crop failures and the high taxes placed on bread. The men in Cairo see their governments as unable to feed their countrymen. The connection between food and political stability has been apparent for centuries. But now, the options for governments are not quite as simple as sending the king to the guillotine.