Feeding Remote Places: When the Last Food Mile is the Middle of Nowhere

Provisioning the dwellers of far-flung places puts all the elements of the food supply chain on display — from production and distribution to preparation and consumption. But how do they actually get it there?

When the unmanned SpaceX Falcon blew up en route to the International Space Station (ISS) in June 2015, 4,000 pounds of food were lost. It was the third consecutive attempt to bring food to the orbiting astronauts that failed. The astronauts — though not in imminent danger — were left hanging.

Although there have been some preliminary, and successful, attempts to grow salad greens in the space station, the astronauts on board remain dependent on rations from earth. Luckily for them, subsequent vessels reached the space station in time to spare them a lettuce diet.

The ISS epitomizes the cliche, “So close, yet so far.” Its orbit is only 249 miles above the earth, but those are some problematic miles to cross. One can imagine the astronauts hovering above the earth, recognizing familiar cities and gazing toward the spot where they know an In-n-Out Burger to be.

And while the ISS is remote, there are many places on earth that are even trickier to get to, with situations that require similarly complex logistics. When feeding the dwellers of far-flung places, all the elements of the food supply chain are on display, including production, distribution, preparation and consumption. How the resulting waste is managed is also a reflection of how far away from home one is. At a certain point, that waste become less of a burden and more of a necessity.

Floating City

The U.S. Navy’s 10 Nimitz class aircraft carriers are the largest ships in the world. Nearly a quarter mile in length, these vessels are like floating cities, with many of the amenities of home, including a variety of foods. Unlike oil-powered ships of similar size that need to refuel every three days, the nuclear-powered Nimitz ships can cruise at 55 mph for 20 years straight — about 10 million miles — on a single “tank” of nuclear fuel.

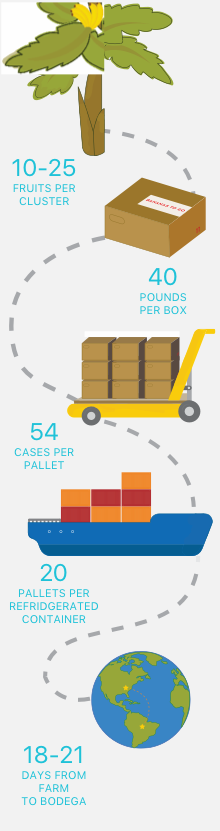

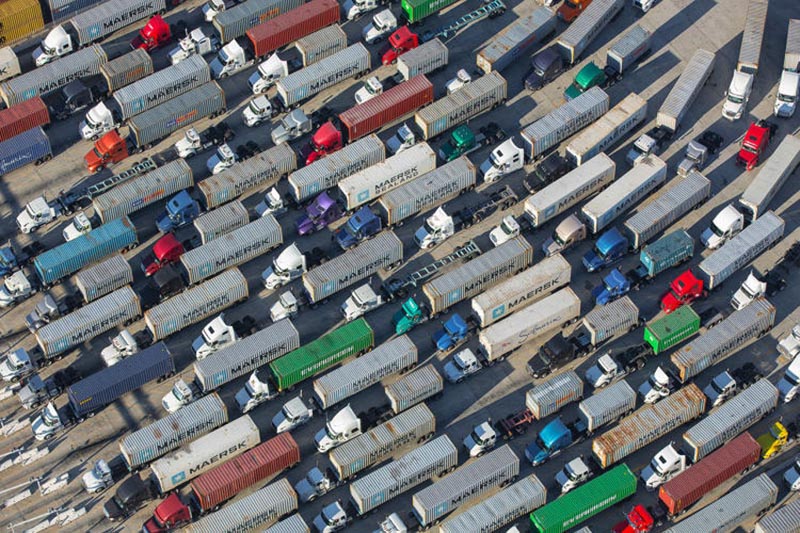

But while the ship’s engines aren’t in danger of going hungry, the 6,000 hard-working sailors on board will eat through 25 pallets worth of food a day — roughly what an average family eats in five years. The ship’s pantries can store more than 60 days’ worth of dried food and 30 days’ worth of frozen, but only approximately two weeks’ worth of fresh fruits and vegetables. Bringing these massive ships to port every 14 days during a seven- to nine-month deployment is neither convenient nor strategic. Instead, the carriers can remain in position thanks to a maneuver known as Replenishment at Sea.

The procedure has the look of an elaborate mating ritual between two ships. They move forward on parallel courses, about 150 feet apart. Sailors on the carrier fire rifles loaded with weighted slugs at the replenishment ship. The slugs trail thin lines to which progressively heavier cables are attached and pulled across the chasm, until cables large enough to be winched connect both forward-moving ships. Eventually, the cables are hooked up to hydraulic rigs and tensioned to several thousand pounds of pressure, and mini cable cars ferry pallets of food (and other goods) between the two ships.

To speed things up, helicopters ferry pallets directly to the carrier’s flight deck, where forklifts are waiting to bring them into the bowels of the ship’s warehouse-sized pantries. Other cables strung between the two ships function as zip lines across the chasm, on which more loads of food travel. As the supplies are loaded, fuel lines are also stretched across, because fighter jets have to eat, too.

For an in-depth look at life on an aircraft carrier, check out the PBS series “Carrier.”

Meanwhile, waste from the floating city is offloaded to the replenishment vessel. Waste plastic, which has been compressed into discs, will be returned to port and disposed of according to local law. Paper products are burned in filtered incinerators. Food waste goes overboard, presumably to the delight of local fish. When far from shore, human waste feeds the fish too.

The basic configuration of cables binding two moving ships was designed by Lt. Chester Nimitz himself—for whom the world’s largest aircraft carriers are named—during World War I. Stationed 300 miles south of Greenland on the replenishment vessel USS Maumee, Nimitz tweaked and refined his system while refueling and replenishing 34 destroyers in difficult conditions during the spring of 1917. Now, as then, time is of the essence in this drill, as both ships are vulnerable to attack when they are intertwined. And accidents happen.

“Any time you put a 95,000-ton aircraft carrier next to a 50,000-ton replenishment vessel in heavy seas, tied together, sometimes King Neptune will reach up and knock things off the line and into the water,” says retired U.S. Navy Captain Dan Grieco. In Grieco’s 30-year career he’s seen only two items lost during replenishment, including an aircraft part, which they recovered after hastily suspending the replenishment and beginning a search operation.

While the replenishment operation itself is a well-oiled machine, its success depends on finding the time to conduct it. During operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm, Grieco says, they couldn’t replenish as often as they wanted, and it wasn’t good. “We were down to drinking boxed milk at times,” he says.

Further Afield

The difficulties involved in feeding an aircraft carrier full of sailors are rooted in the sheer quantities of food and in the windows of vulnerability that open when the food is handed off. But for those who overwinter on Antarctic bases, the challenge is reversed. The number of mouths are fewer, but the intervals between replenishments are considerably longer. And getting there, especially in winter, can be more dangerous than an off-planet jaunt to the space station. In fact, winter travel is so dangerous that even medical evacuations from Antarctica are extremely rare. Winter residents of Antarctica are generally stuck with what ails them until winter breaks. And the same goes for what nourishes them.

On the shifting surface of the Brunt Ice Shelf, on the coast of Antarctica, the British-run Halley VI research station was built on skis to stay atop the ice—something its five predecessors failed to accomplish. And while the Nimitz carriers wait two weeks between replenishments, and the ISS is paid a visit every 40 or so days, Halley IV gets only two visits per year, courtesy of the British icebreakers Shackleton and Ross.

The first visit of the summer season lands just before Christmas, when a seasonal crew of about 100 people arrives. The Antarctic summer doesn’t linger long, and before you know it a ship is back in February to take the snowbirds home. Those two visits constitute the only opportunities for replenishment that the base sees for an entire year. The crew of 11 that overwinters for nearly 10 months must make that food last until the following December atop the hungry ice.

The pantry at Halley VI is stocked with canned supplies and staples that must last through the winter for a crew of 11 to 16. Once the February shipment comes and goes, the pantry won’t be restocked until the following December.

The Christmas arrival delivers a summer stash of fresh veggies, but its main non-human cargo is a year’s supply of frozen and canned goods. The February delivery brings almost exclusively fresh veggies, explains John Eager, a former chef at the base who now does kitchen and meal planning from Halley’s administrative headquarters in the United Kingdom. The nature of the fresh vegetables tends to be along the lines of what you might find in a homesteader’s root cellar.

BUTTERNUT SQUASH AND FETA CHEESE TARTLETS

Take squash that’s just past fresh, roast and freeze it to make this fresh-tasting dish in the depths of the Antarctic winter. The tartlets make a great starter with reduced balsamic vinegar during the 105 days of darkness at Halley.

3 tbsp. olive oil

600 grams squash, peeled and diced

375 grams puff pastry

150 grams feta cheese

1 red chili, deseeded and finely chopped

2 tsp. thyme leaves

Salt and black pepper, freshly ground

2 baking trays, one lined with Teflon sheet

Set the oven to 400°F. Heat a baking tray with 1 tablespoon oil on it. Add the diced squash and roast for 30 minutes, stirring occasionally, until softened. Meanwhile, roll out the pastry and cut into 6 equal pieces. Put them on the Teflon-lined baking sheet. Mark a thin border around each one. Chill for 30 minutes.

Divide the cooked squash and place it on the pastry squares, inside the borders. Crumble cheese over top, then sprinkle with chili and thyme. Season and drizzle with the rest of the oil. Bake for 30 minutes, until golden and cooked through. Serve hot, with reduced balsamic vinegar dressing.

“We stick to hard, dense stuff that lasts a lot longer. Potatoes, carrots, onions, squash, turnips,” Eager says. “They store incredibly well, as the atmosphere is very dry. Eggs keep well, too. We can make them last six months by turning them over every week.”

Because it can take several weeks for the icebreakers to make their way to the station, anything more perishable might not even survive the journey to Antarctica, much less stick around through the winter. “Anything like salad is in a sorry state by the time it gets there,” Eager says.

Frozen foods, meanwhile, are in their element on the frozen continent. While the base itself endeavors to stay atop the ice, most of the frozen goods are buried about 10 feet down — which makes more sense than using electricity to power a freezer.

As veggies like squash approach their expiration dates, the cook will make them last longer by preparing finished dishes and freezing them. Many holiday meals are prepared and frozen months ahead of time.

Waste in Antarctica is carefully dealt with, in accordance to the Protocol for Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, signed in 1991. Solid waste is sent home for incineration, while sewage and greywater are treated on site so that minimal trace is left behind.

Waste may be a liability in Antarctica, with massive effort and expense invested in its disposal. But when you get further away than the end of the Earth, waste suddenly becomes too valuable to part with.

Waste as Fuel

Any journey beyond the moon would reach the limits of the earthly supply chain. It’s not that food couldn’t be brought along; it’s just that replenishments can’t be counted on. If you don’t come back soon you will run out of food — unless you produce your own.

NASA hopes to complete a two-year mission to Mars by the 2030s. SpaceX hopes to get there a decade sooner. The present, consequently, is a fertile time for research into how to feed astronauts aboard space ships and on different planets. Because a growing portion of space exploration is being conducted by private enterprises, much of the research is closely guarded as trade secrets. But the studies being done in the public sphere are enough to shed light on how the space-age food scene could look.

For long-haul journeys through space, and for colonizing Mars, the primary means of food transport will be in the form of information, including knowledge about how to grow plants in space and in alien environments. And no information is more valuable, and less replaceable, than the DNA of seeds. These genetic blueprints are the primary way humans could transport food to places that are too far away to be replenished or to bring sufficient supplies. In the case of the two-year journey to Mars, it may be possible to pack enough calories to keep the astronauts alive. But growing edible plants on board the spacecraft would likely be vital to survival for other reasons entirely.

As plants grow, they remove carbon dioxide from the air and replace it with oxygen. On the long flight to Mars, this action would purify the air on board. Meanwhile, the sequestration of that atmospheric carbon, in the form of plants, would take care of the astronauts’ waste.

The interconnectedness of food, oxygen and waste disposal has led to a focus on closed-loop systems in research laboratories. In one study, rats are being kept alive with oxygen produced by algae. Depending on oxygen levels in the rats’ enclosure and the rats’ metabolic requirements, scientists can shine light on the the algae to trigger photosynthesis, the process by which plants consume carbon dioxide and produce oxygen. This is a simplified version of how astronauts and their food production systems could help regulate their shared atmosphere.

Any food grown in such a system could be considered a byproduct of the processes of waste management and atmospheric purification. The astronauts would have to do their part in the cycle by eating the food and excreting the waste products therefrom. As the astronauts would be eating much more than what they grow, thanks to the food they brought with them, the volume of their waste would likely exceed what they need for their little garden. But that extra poop would not be jettisoned. You don’t throw away gold.

While some researchers are studying the biospheres of space travel, others are looking into how food could be produced when and where the spaceship lands. Dutch scientists are attempting to grow crops like tomatoes, peas and wheat in red earth, dug from a Hawaiian volcano, thought to closely resemble Martian soil. According to Wieger Wamelink, an ecology researcher at Wageningen University, it took a little tweaking and some animal refuse, but plants eventually began growing quite well in the red dirt, which was purchased from NASA. On Mars, he explains, the plants will similarly have some extra help.

“The feces of the astronauts [produced] during the travel have to be stored and brought to Mars, where it can be used as fertilizer,” Wamelink explains.

SEED DATA

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault in arctic Norway has been nicknamed the “Doomsday Vault” because its location and construction were designed to withstand a variety of manmade and natural disasters. North enough to withstand rising temperatures, high enough to avoid tsunamis and rising sea levels, remote enough to survive a nuclear war and deep enough in a mountain to withstand meteorites, bombs and tornadoes, Svalbard has as good a chance as any place on earth of surviving the big one.

While Svalbard is often referred to as a seed bank, it technically isn’t, as no regeneration of seed takes place on site. “We built a tunnel in a frozen mountain and put seeds in it,” explains Cary Fowler, executive director of the Global Crop Diversity Trust, which funded Svalbard’s construction and now covers its operating costs.

Humble remarks aside, Svalbard is no joke. The vault holds copies of seed collections from seed banks around the world, including ancient strains of wheat, lentil and chickpea from Aleppo’s imperiled seed collection. Every time a depositor seed bank regenerates any of its seed, they update Svalbard’s collection, which currently contains 860,000 varieties.

Sowing nitrogen-binding plants like clovers, lupine, green bean and pea is another vital step in the process, according to the Dutch scientists. “Together with nitrogen-fixing bacteria they can take nitrogen gas from the air and turn that into eventually nitrate, which the plants can use for growth,” says Wamelink.

Obviously, growing food in actual Martian soil could present a host of obstacles. The food would have to be grown in some kind of space greenhouse that would be pressurized to Earth’s atmospheric pressure. It would need to be heated, lit and protected from cosmic radiation, which damages plant DNA. Perhaps it could be partially buried, with electric lights at night, powered by solar panels. The first colonists to arrive on Mars will have no shortage of work to keep them busy, as they attempt to construct a real-life biosphere experiment—not in the red sands of Arizona, but on the red planet itself.

Despite the challenges of feeding people in remote places, humans continue to push the limits of their range. When the distance from home reaches the point where growing food is more practical than bringing it, the journey from “farm” to table resets. Space travelers millions of miles from home, counterintuitively, will be eating more locally than the person on Earth who shops at his or her local grocery store. And in the closed-loop systems where plants and humans thrive on each other’s waste, some basic facts underlying the Earth’s ecosystems become crystal clear, even as our home planet fades in the rearview mirror. Food and waste are different sides of the same coin, part of an endless cycle.

If you were embarking on a two-year trip to Mars, what foods would you be sure to take? Tweet us. #FeedingMars