Based on what I saw at the Summit, toasters — and practically all other kitchen appliances — are about to be unfamiliar in every way. Manufacturers promised that my appliances will recognize my face and voice to know my food preferences and biomedical data to produce the most perfect toast the world has ever tasted. And it won’t be a toaster, but a device that may toast, boil, sous-vide, fry or braise. Transforming ingredients into meals will be the goal of our new Smart Kitchen.

Imagine this: Your kitchen in 2030 will use voice activation to operate the handful of kitchen tools and appliances that remain after designers remove wires, Instapots, trash cans and microwaves. Your kitchen will be smaller and wireless, maybe even portable. Croatian startup Dizzconcept makes portable, pop-up kitchens that fit into any space. Perhaps our new homes will come without kitchens, and we’ll simply select these movable, modular, personal kitchens to drop into our new spaces.

Countertops will be charging surfaces for your devices. Screens will be voice activated (so you don’t have to touch a screen with fingers sticky from the syrup dispenser). These new surfaces will show what’s in your refrigerator and pantry, with data about the shelf life of all perishables. Your fridge will sense when you need to buy more milk — and will order it for delivery when your house knows you will be home. Garbi, another startup, is working on a trash can that recognizes what you discard, sorts it for recycling and reorders items.

Recipes will be personalized. No more single recipes from that book on the shelf, printed on paper, that may be good for someone but not you, with your recent calcium deficiencies and preference for mild flavors. Your kitchen will know what’s in your pantry and will design what to cook based on its knowledge about your health and preferences. Big Data for food has arrived.

Where does that leave grocery stores and restaurants? Many will be left out of this new food landscape, while others will get smaller and prepare food for delivery services. Still others will become experience centers, with more grocerants (restaurants in grocery stores) where you select your ingredients and the grocery store chef cooks it for you to eat in the store. Grocery stores, themselves smarter because of all the customer data they now own, will be fulfillment centers, some modeled after Amazon, and many integrated into Amazon’s platform.

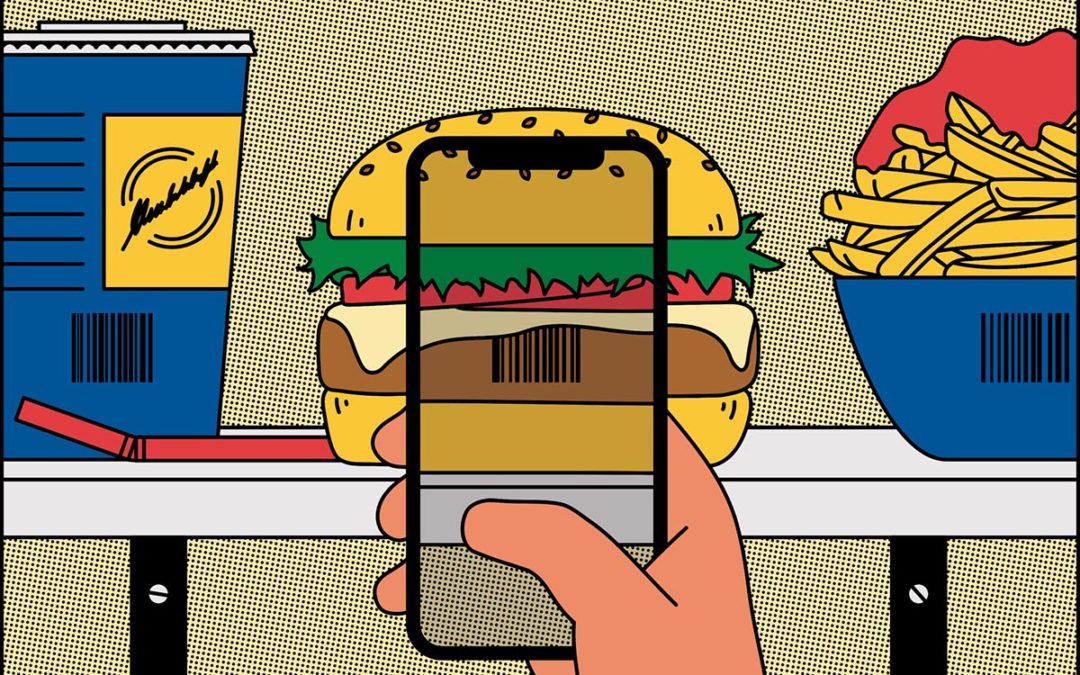

Because your kitchen will be so smart, it will become a commerce center. You will shop from home, with tools such as augmented and virtual reality that give the sensation of being at the store. You will smell and touch what you buy, without the headache of parking or standing in a checkout line.

Perhaps these new kitchens will be maker spaces, educational centers that will teach us how to cook, what to cook and inspire us to tell stories around our food making. We’ll be content makers for a new media — food — a far cry from the static food photos we post on Instagram. We’ll stream our cooking experiences in our kitchens.

And who really likes to peel potatoes or chop onions? Food printers now produce fresh food from organic ingredients, freeze-dried and pulverized. The Last Mile is now no mile at all.

Kitchens, grocery stores and restaurants will be hubs for innovation. The engineers and designers at Bosch, GE, Kenmore and Siemens are fiddling with a whole new world in our former kitchens. Appliance makers have become hardware and software companies. Grocery stores and restaurants will fill new roles as they adapt to these new “platforms,” as our kitchen counters and frying pans will come to be known.

We might miss the joy of cooking. Or the satisfaction of making. Or the delight of creativity and the unexpected. Where along the road of automation will we pause? As our kitchens change into service centers that defrost and heat food delivered to our home, will we yearn for the temperamental toaster?

Wi-Fi

Wi-Fi Bluetooth

Bluetooth Apps on Our Mobile Phones

Apps on Our Mobile Phones Hidden Cameras

Hidden Cameras