by Cory Leahy | Dec 5, 2018 | History, Issue 5, Stories

For centuries, sailing ships offered the fastest, best option for transporting goods and people. The Age of Sail (1571–1862) marked the reign of tall ships, with clipper ships representing the apex of commercial sailing’s progression.

The visually striking clippers had strong lines, V-shaped bows that sliced through water and dozens of sails to capture wind. First developed around 1845 by American shipbuilders looking to give small fishing boats an edge over pursuing pirates, clipper ships evolved to carry modest amounts of cargo at unparalleled speeds. A clipper ship could reach more than 15 knots and cover 300 nautical miles in a day, easily outpacing a steamer ship’s 9 knots.

During the Gold Rush, in 1849 — 20 years before completion of the transcontinental railroad — ships carried 25,000 Americans west. While wealthier passengers could spring for Panama-bound steamers, take the train across Panama, then steam up the West Coast, most forty-niners endured a five- to seven-month journey around Cape Horn via clipper ship. Flying Cloud set a world record for this trip, which stood for more than 100 years, when it arrived in San Francisco after 89 days, 21 hours.

These greyhounds of the sea were the obvious choice for the British Empire’s most prized cargo: tea. Thirst for tea was such that a so-called tea clipper could earn £3,000 from one cargo load — roughly 20 to 25 percent of shipbuilding costs. The first ship of the season to reach London’s docks would win a premium.

The Great Tea Race of 1866 demonstrated the logistics underlying tea mania. Clipper ships lined the docks in Fuzhou. The first ship to clear customs had an early advantage, but favorable winds, stronger tugboats and the luck of the tides made for a competitive 16,000-mile race between five of the day’s fastest clippers, Flying Cloud among them. Ninety-nine days after leaving Fuzhou, Taeping and Ariel docked within 20 minutes of one another and split the premium.

But as 45 million pounds of tea flooded the market, tea prices plummeted, illustrating one of sail’s disadvantages: Ships couldn’t keep a schedule, which meant supply-side volatility.

The Great Tea Race occurred between two dips in the popularity of sailing. When American banks shuttered in the Panic of 1857, trade slowed, as did the demand for sailing ships. Later, in 1869, the Suez Canal opened and gave an advantage to steamer ships, which could complete the Europe- Asia route in 50 days. Overland transport improved, too, with railroad expansion.

By the turn of the 20th century, countries were abandoning sailing ships in favor of steamers, which offered reliability and greater cargo space. With the opening of the Panama Canal and the onset of World War I in 1914, sail’s demise seemed assured. By World War II, sailing ships were restricted to commercial fishing trades. Tall ships seemed destined for nostalgia, until — nearly a century later — the winds shifted once more.

From 2012 to 2017, shipping accounted for 3.1 percent of global CO2 emissions. The International Maritime Organization estimates that shipping emissions will increase by an additional 50 to 250 percent by 2050. As some in the industry look to lower their carbon footprint, there’s renewed interested in wind power.

In recent years, sail cargo projects have sprung up along old trade routes. U.K.-based Grayhound Lugger crosses the English Channel, trading Cornish ale and organic French wine. Dutch-based Tres Hombres crosses the Atlantic with cacao, coffee and rum. Schooner Apollonia plans to launch on the Hudson River by year end, bringing cider, beer and apples downstream to New York City.

In 2019, Sail Cargo Inc. will open a carbon-neutral shipyard in Costa Rica. Through its 3½-year build process for Ceiba (a 45-meter sailing cargo vessel with a chilled hold space and 25-ton cargo capacity, crafted from sustainably harvested wood), Sail Cargo Inc. plans to offer a traditional skills apprenticeship program, where participants can learn shipbuilding, blacksmithing or woodwork — all green jobs.

While sail may have traditional roots, its means have been updated. Today’s sailing ships have biodiesel engines or solar batteries to augment wind power, plus GPS and plotting technologies to plan efficient routes.

Still, challenges remain. Routes aren’t operable year-round, and — as in the past — sticking to a schedule can be difficult. Port infrastructure might be set up for recreational boats with floating docks that make loading tricky or for the giant post-Panamax cruise and cargo ships. What’s more, to realize a profit, sailing ships need premium cargo. Vermont Sail Freight’s founder, Erik Andrus, said only one crop would deliver an ROI of $0.50 to $1.00 per pound of weight: Pot.

Growth potential aside, modern sail freight has neither the capacity nor efficiency to supplant tankers. Instead, cargo shippers will look to wind to lower emissions. Maersk is trialing rotor sails (invented 100 years ago) to add wind power to tanker ships, which will conserve some 1,000 tons of fuel. And Cargill, which charters over 500 vessels, is co-funding SkySails, a kite sail initiative.

Sail freight’s early adopters are largely companies with the desire (and cash) to align their business with their values by using emission-free shipping for organic, hand-crafted products. Other clients value the interactive marketing experience sail cargo offers: Guests can board the ship, sample products and form a powerful brand connection.

Unlike sailing ships of yore — which competed as fiercely as any 21st-century big-business rivals — today’s sailing ships operate as a network, sharing tips and routes. That unusual collaboration highlights the focus on relationships that could cement this trend as a viable shipping option.

Jason Marlow of Schooner Apollonia acknowledges that sail cargo’s client base is limited at present. Yet, he is optimistic. The more people start to identify sail transport as an option, the more they will request it.

“As it starts to scale up and there are more vessels and it’s more connected, then it starts to compete pricewise with other modes” of transportation, Marlow says. In the meantime, the new-old industry breathes life into port towns that may be struggling to redefine their economies.

by Cory Leahy | Jun 18, 2018 | History, Issue 4, Stories

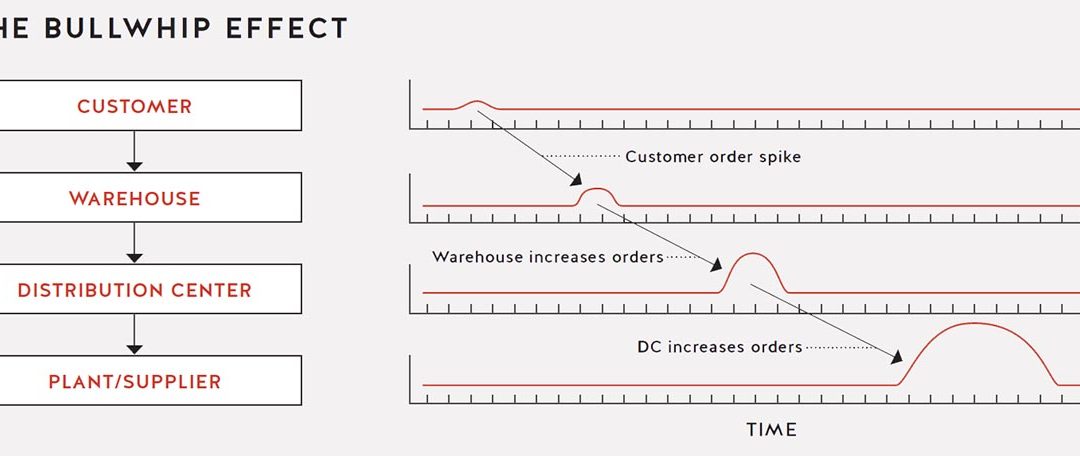

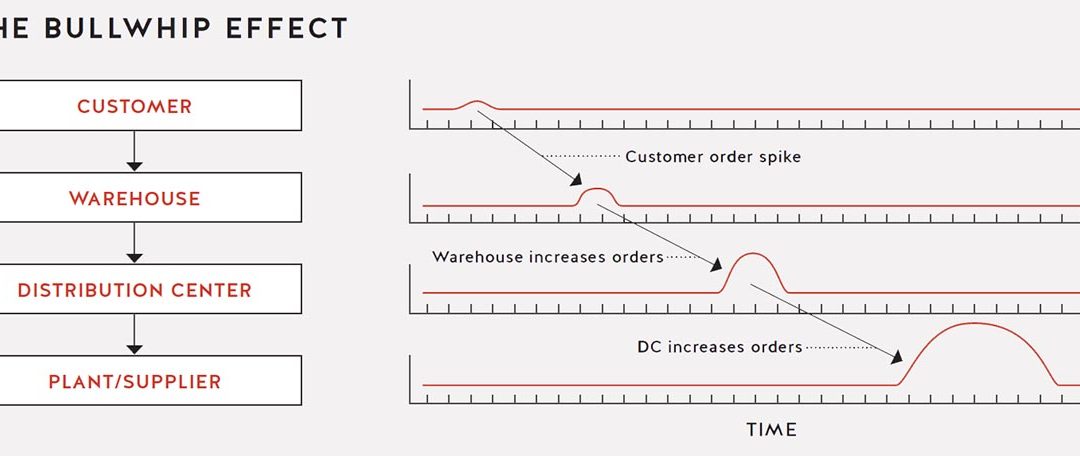

Only at MIT would students play a “Beer Game” to understand a supply chain phenomenon called the Bull Whip Effect. When you’re holding a whip, a small flick of the wrist creates ever-increasing amplitude down the length of the whip. It’s a problem food distributors deal with all the time because even the smallest variation in consumer demand can increase chaos and unpredictability upstream.

Jay Forrester, a professor at MIT from 1956 to 1989, devised the idea in the early 1960s to illustrate how supply chain forecasts can create inefficiencies. In the Beer Game, a single item — a case of beer — travels through a multilevel distribution system in a supply chain. Players operate four stages of the supply chain, and the objective is to order beer and deliver it to customers. Sounds simple, right? Not so fast. The simple act of a player changing the amount of beer ordered sends a ripple throughout the supply chain.

As consumers — the demand side — change their behavior, the supply side adapts inventory and warehousing activities. Players also blame each other for feedback failures that result in a lack of beer. But a build-up of supplies in a warehouse also reflects a communication breakdown between consumers and producers. You lose if you create a large inventory while trying to adjust to the change in orders. Product sitting in a warehouse costs money, so having a stable supply chain and deftly adapting to changes in demand is the winning play.

Research shows that a variation of as little as 5 percent can lead to a variation of 40 percent up the chain. For example, if consumers order fewer bottles of beer, the grocery store will send a message up the supply chain. (“Up” in supply chain lingo means moving from farm to the table; “down” means moving from table to the farm.) That 5 percent decline in beer sales in April could lead to inventory build-ups within the chain, over- ordering of packaging material, and misguided communication between brewers and ingredient producers and processors.

Another way this concept affects the food supply chain is when weather forecasters predict bad weather. A prediction of icy roads in Texas leads to a rush on grocery stores to purchase food while roads are clear. Store shelves empty, and the store’s procurement team returns to its inventory system to squeeze out more stock, while suppliers downstream scramble to find additional ingredients or sources.

As Beer Game players discover, one strategy for variation in consumer demand is to have extra inventory on hand so they can absorb a temporary uptick in demand. But storage costs money, and many food suppliers, intent on creating a “lean” supply chain, want to minimize inventory to save money and avoid food waste. Sometimes, when consumers stop buying a product, stores offer discounts and promotions, but that may cause unpredictable surges in sales that create more problems downstream. You can only hold onto tomatoes for so long.

Forecasts seem to be the culprit here, and the bullwhip effect is more about the problems in forecast-driven supply chain than in supply chain dynamics in general. If your supply chain depends less on forecasts and is more aligned with actual consumer behavior, the bullwhip effect may be dampened. Food companies that link point-of-sales data and supply chain planning can tighten the loop between consumer behavior and other activities throughout the supply chain.

If nothing else, the Bull Whip and the Beer Game reveal the systems effect of the food supply chain. Everything is connected, and one failure has dire consequences. Lack of beer is just one of them.

by Food+City | Jan 31, 2018 | Food Tracks Blog, History, Stories

The Kimball Art Museum portrays a side of the meat business many visitors to Forth Worth, Texas, don’t see. If you only toured the Stockyards outside the museum, you’d miss the preceding centuries of carnivorous history.

In the late 1580s, Annibale Carracci painted two canvases that give us an idea of how meat fit into urban landscapes during Italy’s colorful Renaissance. By the late 16th century, Renaissance art entered the period of Mannerist painting, which led to the Baroque period, when the ideal proportions of High Renaissance art became exaggerated and even distorted. In the early 1580s painting, The Butcher’s Shop, Carracci’s two butchers and their gory background are examples of less-than-idealistic settings and out-of-proportion humans. The animal bodies outweigh the human bodies, and heads become dwarfed by torsos.

Called genre paintings, these images of everyday life stand in sharp contrast to the mythic portrayals of religious figures that hung in the Italian churches. Carracci, in one of his two paintings of butchers (the other, larger butcher scene is in the Christ Church Collection, Oxford, England), shows us one day — any day — in the life of a 16th-century butcher. He knew their lives because several of his family members were butchers in Bologna.

“One looks directly at you in defiant confrontation, as if he’s daring you to accept the reality of his profession with all its gore.”

There are two butchers in the Kimball Museum painting. One looks directly at you in defiant confrontation, as if he’s daring you to accept the reality of his profession with all its gore as he holds out a cut of meat for consideration. The other, eyes cast downward toward his knife, is preoccupied with the work of the day. Carracci studied with Titian in Venice, and the latter’s iconic red spills onto the canvas. There’s no blood on the floor — it’s not that messy — but the hanging carcasses are almost like stage backdrops surrounding the two men as they display their art and prepare for the next animal to slay. Nothing glorified here, but everything to see.

The carcasses suspended from sturdy meat hooks above the two figures appear to be from sheep. One sheep’s head lies at the feet of one of the butchers, one of its eyes cast in the direction of another sheep hanging above, eviscerated and waiting to be skinned.

A beef carcass dominates the left-hand side of the painting, cut in half as is still the custom for wholesale cuts of meat, which today would include all eight primal cuts. (Those are chuck, rib, loin, round, flank, short plate, brisket and shank.)

We can’t tell from the painting if these are retail or wholesale butchers, but both existed throughout Europe at the time.

Outside the Kimball

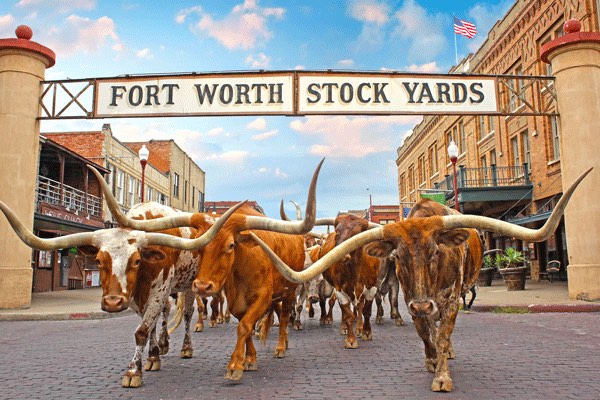

Outside the museum are the Fort Worth Stockyards, whose story is more familiar for Americans who know about the role that Forth Worth played in the history and development of the U.S. meat industry. The names of Armour and Swift, written in the embankment that surrounds the Stockyards, tell visitors who made Forth Worth the largest feeder of cattle from the Western ranges.

The entrance to the Fort Worth Stockyards, from fortworth.org.

In their new incarnation as a tourist site, the Stockyards entertain visitors with twice-daily reenactments of cattle droving. Texas Longhorns plod silently down the street attended by cowboys located in the traditional positions of a droving team.

Inside the surrounding buildings, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, packing houses practiced the art of butchering in much the same way as those Italian butchers in Carracci’s paintings. Now, in Brooklyn and other foodie destinations, shops like those in the paintings are few but gaining more appeal as consumers demand more transparency between their food (meat in this case) and their plates. Perhaps it’s time for a contemporary painter to record those new Brooklyn butchers — pristine white aprons and all.

by Cory Leahy | Sep 5, 2017 | History, Issue 2, Stories

We increasingly want more information about our food. We want to see, at least once, the faces of those who bring food from fields to plates. The farther we’ve gotten from the farm, the more important transparency has become. To better understand a system that is largely invisible, we need an introduction to food logistics. History is a good place to begin.

Ever find yourself behind a double-parked truck? Most likely, it’s delivering food. Trucks covered with images of pizza or a cornucopia of vegetables make their way into the hearts of cities around the world daily, and we hardly take note — except when they block our way to work. But truckers aren’t the only ones who dispatch our daily food supply. Container ships, cargo planes, bicyclists, camels and trains all conjoin in one complex global supply chain.

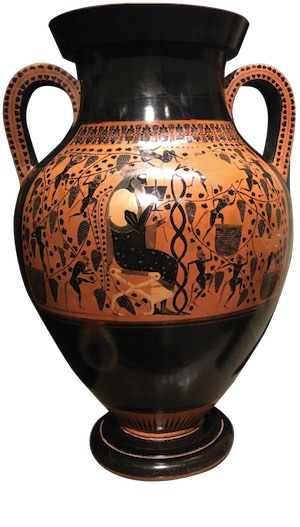

Although the tracks of our food as it travels today are well hidden, the flow of the food supply chain has existed for millennia. Pack animals and olive-oil-bearing clay amphorae delivered food from source to consumption before the birth of Jesus. But logistics, the complex systems that optimize the flow of food, originated with Alexander the Great.

FORAGE AS FUEL

The concept of logistics appeared far earlier than the word. The word first appeared in the late 19th century to mean the art of moving and maneuvering armies, including their supplies and food. The first logisticians — working long before the 1800s — had to consider the seasonality of fodder, food for transport animals, the lack of roads for wheeled transport and the scarcity of ports, storage facilities, depots and communication networks.

During the fourth century BC, the Greek king Alexander the Great assembled an empire that stretched from Asia to Africa. His success was largely due to his understanding of logistics, the strategic movement of men and weapons that factored in harvest calendars, geography and the need for single points of control.

Other military commanders improved on Alexander’s strategies for moving food and materiel. For them, having seamless logistics was a combat strategy. When Hannibal Barca, a Punic commander from Carthage, crossed the Alps in 218 BC, more than 30 elephants joined his army. The imminent snowfall would slow their progress and make it impossible to reach their enemies in Italy. The logistics of moving his army and the food to feed his troops was complicated enough. But the challenge of feeding the animals that transported the food proved impossible.

“The Elements of the Science of War” appeared in 1811, written by an engineer named Wilhelm Muller. He wrote about military campaigns going back to 1667, citing the importance of balancing troop movements with the need for “victuals” and forage.

While today we move food to cities on various forms of wheeled and non-wheeled transport networks, our networks run on fossil fuel, not forage. Early logisticians were faced with the vagaries of growing seasons, changeable weather and the limited availability of enough forage to keep their equine and elephantine transport on their feet and moving. While we struggle to keep food cold and extend shelf life, those early logisticians had much more to contend with. Like no roads.

On this amphora, you see Dionysus, the Greek god of the grape harvest and winemaking, drinking wine while satyrs make wine — an illustration of the journey from vine to cup.

Victuals

Food or provisions, typically as prepared for consumption.

EARLY HIGHWAYS

Roman roads are mentioned in nearly every tourist guidebook. The Romans developed complex procurement and distribution of food supplies, mostly because the republic and then the empire did not produce enough food locally to feed its growing urban populations. While the Assyrians and Greeks knew how to feed their soldiers, it wasn’t until the Romans developed a complex system of roads, taxation and administration that the idea of optimizing the movement of food took shape. Roman roads and bridges show us how they distributed food across the empire.

Centuries later, when Napoleon led his Grand Armée to conquer Russia in 1812, he drew upon Greek and Roman logistics to enable his troops to stay in the field longer, sustained by a ready supply of food while destroying the supplies of their enemies. But his march on Stalingrad wasn’t so successful. The Cossacks in his path resorted to destroying food supplies along the way. Napoleon’s rations and forage for his animals were soon depleted as the Russian winter closed in. In the end, Napoleon lost almost 400,000 troops. His defeat precipitated his fall from power and the unraveling of the Napoleonic Empire. Logistics proved to be his nemesis.

As the Industrial Revolution mechanized much of civilian society, Frederick Winslow Taylor introduced the concept of the scientific management of process manufacturing. He promoted practices that optimized the workflow while eliminating waste. These included standardizing parts and practices as well as carefully measuring and maximizing the use of time and labor. Taylorism, as his theory was called, led to further developments that looked at how to produce and move products from factory to consumer. Food production was one of many processes that became Taylorized.

The food supply chain differs from other supply chains in its requirement for careful temperature control. The development of ice manufacturing and refrigeration led to the development of what is now called the cold chain. Entrepreneurs such as Augustus Swift revolutionized the meat supply chain, utilizing refrigerated rail cars and vertically integrating all aspects of meat production.

Railroads began to move food across long distances beginning in the mid-19th century. Shipping containers, developed by Malcom McLean during the 1950s and 1960s, transformed how food moved on ships, trucks and railroads. The integration of these transport networks eventually became our international, intermodal food distribution network. When computers arrived during the early 1950s and 1960s, the idea of logical workflows got an extra push through the acceleration of data processing. The development of computer-based forecasting systems and materials requirements planning came next. It wasn’t until the 1980s, however, that supply chain management became a thing, leading to the emergence of supply chain departments and centers in academic institutions. And now, food logistics has its own professional organizations, conferences and publications.

Look for this historical narrative to go into hyperdrive as railroads, computers, tracking devices, drones and robots bring new speed, safety and personalization to our daily meal.

Process Manufacturing

The production of goods typically produced in bult quantities — as opposed to discrete and countable units — including chemicals, food and beverages, gasoline, paint and pharmaceuticals.

by Food+City | Jul 24, 2015 | Food Tracks Blog, History, Stories

George Huntington Hartford and George Gilman, 19th century entrepreneurs, would flinch at this week’s news that the A & P grocery store chain was filing for bankruptcy. The two Georges created the iconic grocery chain in 1859 and built what we now know as the grocery supermarket. They developed the model for grocery stores that sell low-priced food across the U.S. Now, for the second time in ten years, the beleaguered company has less than 300 stores, down from the 16,000 it operated in 1929. The demise of A & P, the oldest supermarket chain, may be the beginning of the end of the big box, super-sized grocery chains.

Similar to the grocery industry, other economic institutions and industries — banks, taxi services, healthcare, and the hospitality industry — are experiencing “creative disruption.” And food distribution is ripe for repair. The local, personal, and transparent is colliding with accessibility, price, and quality. George Hartford and George Gilman, founders of The Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company, led the first wave of destruction by putting thousands of corner grocery stores out of business at the beginning of the 20th century, and now the effective equivalent of small and local distribution centers may be our future food distribution system.

Marc Levinson’s book, The Great A & P and the Struggle for Small Business in America (2011), tells the story of the rise of big grocery chains from the 1920s until the present day — and how A & P became the world’s largest grocery store chain. Levinson tells us how A & P innovated its way to success only to be come under attack for practices that benefited middle-class consumers by making low cost food accessible. A & P couldn’t find a way to re-create itself amidst pressures from low-priced competitors such as Wal-Mart and high-end stores such as Whole Foods.

By the 1950s the company began a long decline into bankruptcy, unable to resuscitate itself after the onslaught of regulations, attacks, competition, and the loss of its founding team. By building a new aggregated, or “combination store,” as the first supermarkets were called, Hartford and Gilman created often aggressive and innovative ways to bring down the cost of food. Buying directly from food producers instead of wholesales, A & P created some of the first discounted grocery stores. They vertically integrated some activities, such as baking their own bread. They contracted directly with farmers who grew crops specifically for A & P and developed recycling systems for packing materials. The consequence of the new A & P model was the demise of the mom-and-pop grocery store in the early 1920s.

These new approaches to food retailing benefited from the appearance of new technologies that directly improved access to food at lower costs. The first commercial refrigeration systems replaced huge blocks of ice and enabled A & P to hold more inventory. Shoppers could buy enough food for one week without returning for perishable meats and poultry on a daily basis. Open access to food products eliminated the need for a shopkeeper, lowering the store’s operating costs. And when cellophane was developed in France in 1909, the new transparent wrapping material made it possible for consumers to see the food they purchased, a development that increased consumer confidence in food safety.

A & P’s new model encountered feisty competitors and the ire of unions and wholesalers. They fought alongside politicians to push against the growth of the supermarket, joining politicians, journalists and industry associations that accused the brothers of “unfair completion.” The excesses of the Gilded Age and poverty left behind in the wake of the stock market crash in 1929 placed big business in the political crosshairs. Franklin Roosevelt, running on his Progressive ticket, set up regulations, oversight agencies, and rules that threatened the competitive advantages of A & P. Roosevelt called the company a “gigantic blood sucker.”

Accusations of “unfair competition” threaten today’s startups. Taxi cab drivers in both Massachusetts and California are among the many threatened by new economies. Taxi companies have united to sue Uber for “unfair competition.” Ironically, unions are cited by A & P as a significant reason for its bankruptcy filing. A & P officers say that union demands for benefit increases are key to the company’s inability to cut operating costs.

But the accusation of unfair competition raises questions about our current economic landscape. Companies have new competitors, often outside of their traditional industry. Wal-Mart competes with Amazon. And Wal-Mart may be competing with itself. Charles Fishman’s 2006 book, The Wal-Mart Effect (How an Out-of-Town Superstore Became A Global Superpower) suggests that Wal-Mart is so big that their practices are no longer unfairly competitive. Rather, the company is so big that it creates its own market forces. Other big supermarket chains, including Kroger and Costco, both cut their costs to compete with Wal-Mart to offer consumers lower prices.

The tension between Big Box grocery chains and small, independent food retailers continues today, fought with digital weapons and by new players, such as Amazon and Instacart. Signs of the disruption of the grocery industry are apparent across several sectors, from UPS to Google. The re-imagined grocery story is taking shape as a response to the newly food-aware customer who searches for healthy food from a transparent, hopefully human or human-like provider. And the landscape for food distribution may look very different in ten years, populated by Amazon, public food lockers, and encapsulated meals. Amazons’ “buy” button brings customers closer than ever before to a virtual warehouse. And the FAA released regulations for drone tests, the mini-aero service.

Hartford and Gilman’s legacy of supermarkets and low-priced food may continue to be with us but in a new incarnation, more as an aggregated virtual supermarket that utilizes high-tech, “last mile” delivery options. Let’s hope that our future food distribution system will continue to provide better food to more people at low prices. And maybe A & P will re-emerge, making George Hartford and George Gilman proud again.

by Food+City | Nov 24, 2014 | Food Tracks Blog, History, Stories

What does a remote Norwegian island 800 miles from the North Pole have to do with our food supply? Much more than you may think. Dr. Cary Fowler, speaking at the American Livestock Breeds Conservancy’s (ALBC) Annual Conference last week in Austin, Texas, explained how the Svalbard Global Seed Vault will protect global crop diversity for the next few millennia. Rarely covered by media and or included in the public debate about our food system, these genetics preservationists are vital to the sustainability of future food production.

Listening to his description of the frigid Norwegian facility were about 75 rare livestock breeders, enduring one of Austin’s coldest autumn days with temperatures plunging into the “horrifying” low of 40 degrees. Gathered in a warm room, these mostly hobby farmers who tirelessly raise livestock such as Mulefoot hogs, gazed at Fowler’s images of a tunnel opening thrust into blue-ish Arctic glaciers.

The president of the ALBC, Dr. Eric Hallman, connected the room full of animal breeders to the business of seed breeding. For the past 40 years, the ALBC has been supporting farmers and ranchers who conserve genetic diversity in domestic livestock breeds as our food system has settled on a few breeds for our world’s large-scale meat production.

The selective breeding of livestock that draws upon specialized animal genetics increases the productivity of our protein supply. This practice has turned over less commercially viable genes to a small group of rare livestock breeders, many of whom were in the room that night.

Dr. Fowler shared his stories about the process of building the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, located on the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen. Working with the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), Fowler led an international team of government agencies, foundations, and private companies to build a secure vault to conserve hundreds of thousands (800,000 samples at last count) of the world’s seeds. The goal is to protect crop diversity against any natural or unnatural disaster. Before the vault was built, many developing countries, some of which are politically unstable, maintained seed vaults that were inadequate. A vault in the Philippines was flooded during a typhoon, destroying many of the country’s valuable seeds.

With predictions that the demand for food will increase by 60 percent during the next three decades, the need for conserving diversity in both crops and animals is critical. The future food supply won’t be produced by these rare breed and seed genetics but instead enhanced and invigorated by these genetics conservationists. Without these conservation efforts, plant and animal adaptations, ever more critical during this time of climate change, will be severely limited. Let us not forget that it was Charles Darwin in the mid-19th century who pointed out the connection between genetic diversity and adaptation.

The U.S. has been involved in promoting seed diversity, also during the inventive 19th century. The predecessor of the USDA, the US Patent Office, began to distribute seeds during the early1800s. The office sent small packets of seeds to farmers throughout the US, inviting them to experiment with the seeds, dispersing and sowing crop diversity, which is still evident today. The farmers planting those seeds created crops that adapted to local and regional conditions.

Because US farmers may have over 50 percent of the world’s wheat genetics, they are increasingly under the mindful eye of the government’s national security agencies. After 9/11 and a sequence of natural disasters such as Katrina in 2005, the USDA and other government agencies saw the protection of genetics underlying our food supply to be as important as the protection the nation’s infrastructure. The increasing sense of international insecurity and the concern about feed our growing world population brings together both the tiny island vault near the Artic and the small group of rare breed farmers listening to Dr. Fowler kindred souls. And while the Svalbard Seed Vault is a monument to Fowler’s astute leadership and international cooperation, these small farmers have no visibility in the current public conversation about food security. We should change this by sending the ALBC a little love.

You can reach them here: http://www.livestockconservancy.org.

Watch Ceiba’s building progress through a

Watch Ceiba’s building progress through a