Tsukiji on the Verge of Change

During the chaotic early-morning auctions, some of the best seafood in the world passes through the crowded stalls, bound for restaurants in Tokyo and around the world. How will this beloved institution handle a controversial move to a new location?

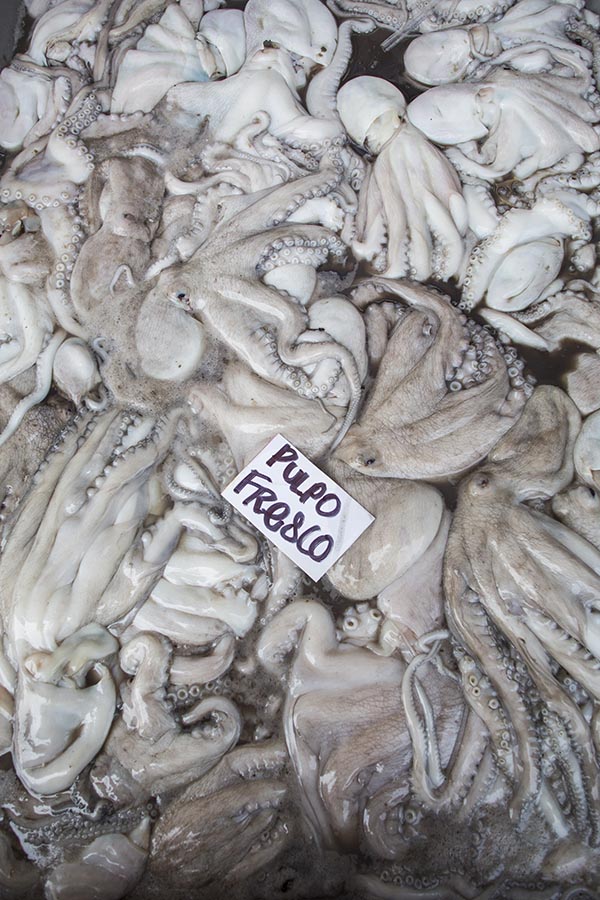

Tokyo’s Tsukiji (SOO-kee-jee) Market is the largest wholesale fish and seafood market in the world. Nearly 2,000 tons of fish pass through the market daily. Everything from flounder, red snapper, mackerel and bonito to uni (sea urchin), conger eel and blue crab — more than 400 different varieties of fish and seafood — is found there. It’s a veritable edible fish aquarium, where one can see thousands of sea animals, living and dead, fresh and frozen, whole and sliced, stored in tanks, Styrofoam boxes and containers of all shapes and sizes. The whine of circular saws cutting through chunks of frozen tuna mutes the sound of machetes as they hit cutting boards, swung by apprentice wholesalers like samurai swords. Seafood and fish sit in boxes just above the ground, the floor wet from melting ice. This market has rows and rows of narrow aisles, a line of stalls that seems to never end.

Despite being regarded as an eternal institution, Tsukiji is on the verge of a controversial planned move. The old facilities, built in 1935 and squeezed between the Sumida River bank and Ginza shopping district, were scheduled to close in November 2016, when the market was to move to its new location two kilometers to the southeast in the less central area of Toyosu. But lingering doubts about the environmental quality of the new premises and ongoing soil tests prompted Tokyo’s new governor to push the schedule out to 2017. Since the government announced the move in 2010 — citing, among other reasons, the need for larger and more modern market facilities — nostalgia about the end of an era for a major institution in Toyko’s sushi culture turned the spotlight on Tsukiji Market and raised questions about what this local market means for Tokyo and the world.

Nihonbashi Fish Market

Boats docked at the old fish market in Tokyo’s Nihonbashi district in the 1890s. The predecessor to today’s Tsukiji Market, Nihonbashi was located right next to the famous Nihonbashi Bridge, the point from which even today all distances to the capital are measured. For hundreds of years the smell of fish and the shouts of fishermen, brokers and peddlers penetrated the air. But the market was destroyed by the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923. Tsukiji was completed in 1935 in nearby Ginza.

ANATOMY OF A MARKET

Tsukiji was built to be Tokyo’s central terminal wholesale market after previous wholesale markets were destroyed in the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake. Tsukiji Market, however, claims a longer heritage as successor to the former Nihonbashi Fish Market, which dates back 400 years to the start of Edo-era Japan. Indeed, Tsukiji traders refer to the paved loading slots for buyers’ truck deliveries as “chaya” (teahouses), a vestige of the old Nihonbashi Market era when buyers waited in teahouses alongside the Edo Embankment for the proper tides to carry their out.

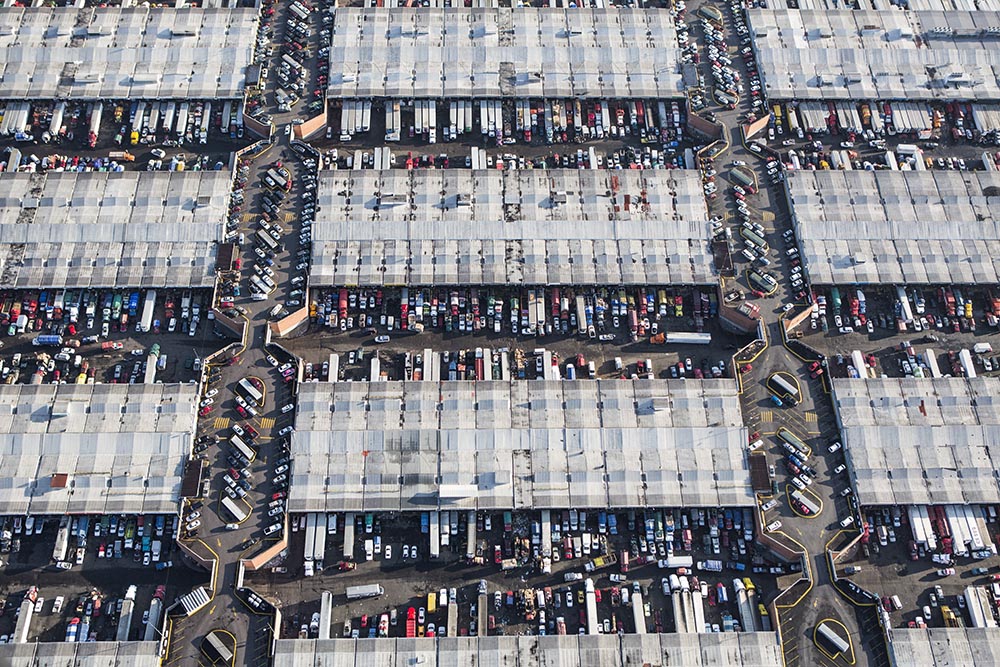

The physical market at Tsukiji is divided into the inner (jonai-shijo) market — mostly fish and produce wholesalers — and an outer market (jogai-shijo) of mostly retail shops running along the streets just outside the inner market facilities. The inner market — the part slated to move to Toyosu — is a gigantic structure with 20 major auction pits for the seven largely family-owned auction firms, 1,677 stalls for some 600 intermediate wholesalers and 250 loading slots for buyers’ delivery trucks. The outer market shops comprise some 500 additional businesses consisting of fresh and processed fish, seafood and produce stands, sushi restaurants, and Japanese kitchenware and cutlery shops; these enterprises will remain in a new building in the Tsukiji area following the inner market’s migration. Roughly 60,000 people work at the market, the vast majority of whom are planning to move when the time comes.

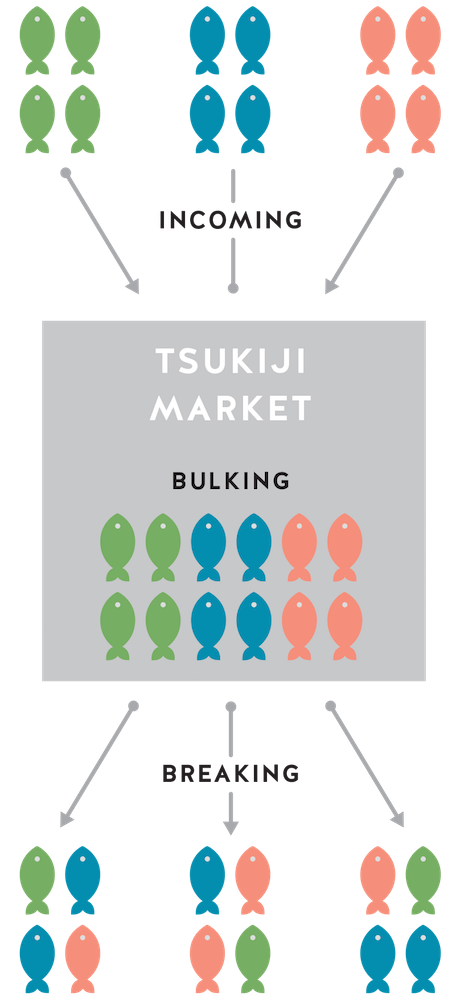

Few Tsukiji Market outsiders understand its inner workings better than Harvard anthropologist Theodore Bestor, whose book, “Tsukiji: The Fish Market at the Center of the World” (2004), remains one of the best windows into the market’s cultural and economic structures. Bestor describes the Tsukiji buildings as being laid out to follow a market logic of “bulking and breaking: to bring in products from all over and aggregate them (bulking) and then sell them [to multiple buyers] in usable portions (breaking).” Sea animals that converge at the market from all over the world are reassembled by auctioneers by type and quality and then distributed out again to restaurants, shops and supermarkets, freshly refashioned as commodities.

Market regulars, according to Bestor, refer to Tsukiji as “Tōkyō no daidokoro” or “Tokyo’s pantry.” As the principal supplier of fresh fish and seafood for Tokyo’s restaurateurs and supermarkets, Tsukiji follows a different rhythm from the rest of the city. Its workday starts at 5 p.m. with fish and seafood being shipped in from around the world during the evening. By 3 a.m. workers from auction houses have unpacked the shipments and laid out the seafood by variety, size, catch zone and quality. The famous tuna auction starts at 5:30 a.m., while hundreds of other specialty auctions run in parallel. The auctions are over by 7 a.m., and intermediate wholesalers take their orders away to sell to city buyers, restaurants and retailers throughout the morning.

By 11 a.m. most market vendors have tidied up their stalls, and by 1 p.m. Tsukiji Market pauses for a rest. Cleaning crews wash down the facilities and recycle the tons of Styrofoam used that day. Perhaps the most startling feature of Tsukiji is how little inventory remains at the end of each day. It’s a place that relies on a “low-tech, high-touch trade,” even today. That kind of selling efficiency relies on longstanding relationships between sellers and buyers, Bestor suggests. Vendors know how to clear their inventory and find buyers for everything, so the next day’s stock will be fresh.

Tsukiji by the Numbers

Tsukiji Market is bustling with businesses and workers each day. While it was built to receive shipments from the port, the reality today is that most products arrive by truck.

Bulking and Breaking

Tsukiji is laid out to accomplish a market logic of “bulking and breaking,” explains Tsukiji expert Theodore Bestor. Products are brought in from all over the world and aggregated (bulking), then sold to multiple buyers in usable portions (breaking).

QUIRKS AND WORKAROUNDS

Despite its operational competency, the physical market at Tsukiji is showing its age. As early as the 1990s, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government began discussions about renovating the market, plans that fell through because of the great expense of renovating existing facilities and because of the financial crisis at the time. Now 80 years old, the facilities are out of date and suffer from wear and tear. But the market’s deterioration is only one factor in the decision to relocate — Tokyo’s bid for the 2020 Olympic Games is another. In 2010, Shintaro Ishihara, then Tokyo’s governor, defended his government’s decision to move the market to a new location, exclaiming, “The market is so old that ceiling sections would collapse in a minor earthquake!”

Since the market’s opening in 1935, the fish trade industry has also undergone several dramatic changes that have affected how the market runs, including the rise of distant-water fishing in the 1950s, the shift from boats and railroads to trucking and airfreight, and the growth in frozen seafood trade and international fish trade since the 1970s.

As a result, workers have become accustomed to certain “hacks” required at Tsukiji. Vendors and auctioneers use bags of ice to keep fish and seafood cold in the non-climate controlled building, resulting in soggy, damp floors. In contrast, Toyosu will be a closed, refrigerated environment. The old market was built for shipments to arrive from the port, but since the 1960s most fish arrives by truck. This means that stevedores must bring incoming consignments in from the exit. Turret trucks race through narrow aisles, rushing purchased products from auction floor to vendor stall to buyers’ loading slots, creating a hair-raising flow of traffic inside the market.

These hacks and market workers’ persistent habits lend an endearing but mind-boggling charm to the old market: How can so much fish move through a market by such low-tech means? “You will still see fax machines being used at the market. So crazy!” says Yukari Sakamoto, a chef and sommelier who runs tours through Tsukiji and authored “Food Sake Tokyo” (2010). The low-tech quaintness contributes to the market’s mystique. Tsukiji in many ways flows from Tokyo’s shitamachi culture — a traditional, mercantile culture seen to be rougher and more authentic than the upper-class, modern yamamote culture. Tuna vendors wield machetes like samurai warriors, slicing tuna with precise, careful cuts reminiscent of martial arts choreographed patterns, or “kata.” Tsukiji has what Bestor calls “a kind of nostalgic shabbiness” that has made it popular with tourists for decades.

Kiyoshi Kimura, president of Kiyomura K.K, poses for photos with a 180.4 kilograms (397 pounds) fresh tuna after this year’s first auction at Tsukiji Market on January 5, 2015 in Tokyo, Japan. A fresh whole tuna weighing 180.4 kilograms (397 pounds), sold for 4.51 million yen (approximately $37,500) by Sushi Zanmai, a Tokyo-based sushi chain operator. Image: by Ken Ishii/Getty Images

Its quirky character belies the market’s increasingly global importance. Tsukiji is a worldwide hub for certain specialty products and high-end goods that will travel to the four corners of the earth. According to a Japan Times report, an estimated 42,000 buyers and 19,000 trucks pass through the market daily. Auctioneers’ decisions about how to categorize and grade fish set global standards. For instance, airfreighted Atlantic bluefin tuna has become the iconic trade at Tsukiji. The tuna auction is big business and sees sales of tuna in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. At the New Year auction (hatsumaguro) in early 2017, restaurant owner Kiyoshi Kimura paid more than \\74 million (about $650,000) for a 467-pound bluefin. The purchase — his sixth such auction win in six years — was largely a publicity stunt: The high price is well over actual market value. But it indicates the extravagance and visibility of the tuna auction worldwide.

Despite these showy sales, Bestor says the volume has been down for the past 15 to 20 years. “The deflation and stagnation of the Japanese economy since the early 1990s led to a tightening of consumers’ belts,” Bestor explains. Another factor is an increase in direct sales. “More important is the expansion of supermarket chains and chains of restaurants (including the kaitenzushi, or conveyor-belt sushi chains), which bypass the market and purchase at least some of their seafood directly from suppliers in Japanese fishing ports or international importers.”

Buyers inspecting the day’s catch of fresh tuna before the auction begins.

KAITENZUSHI

A fast-food sushi restaurant in which plates of sushi travel through the restaurant on a rotating conveyor belt that runs by every table and counter seat. Customers select the sushi they want to eat as it passes by.

Mixed Blessings

Nevertheless, Tsukiji is as popular as ever with tourists — who may or may not feel welcome during their visits. In early 2016 the Tsukiji Market shortened the public visiting hours, opening at 10 a.m. instead of 9 a.m., because the increased foot traffic of tourists there to see the original market before its planned move was blocking the flow of narrow aisles between stalls. Warning signs at the entrance clarify that tourists could outstay their welcome if they get in the way of fast-moving workers, transport vehicles and businessmen.

In contrast, the new Toyosu site is decidedly poor for tourism. The three main buildings are divided by large streets that are hard for pedestrians to cross. Tourists may see the produce and seafood markets only by looking down from second-floor glass windows. While this allows more people to watch the tuna auction, the sense of being in the middle of the action has disappeared now that tourists can no longer walk right next to the fish. Toyosu is also disconnected from Tokyo’s centers of consumption and, unlike Tsukiji, has no local community history. There is also no metro station at Toyosu, only a monorail stop that is much less convenient from the city center.

For market insiders, the planned relocation of the inner market to Toyosu is a mixed blessing. Tsukiji Market has an area of just 23 hectares, while the new facilities at Toyosu encompass 40 hectares. This added space has allowed designers to build the facility to favor big-scale business, and to bring the market up to date on global food safety regulations. Toyosu is connected to highways that run directly to Haneda and Narita airports, which will improve airfreight business. And Toyosu will have multistory buildings with elevators to move seafood — though some worry about how this new logistical feature might impede or complicate the flow of goods around the market. Others have voiced concerns that passageways in the new market might be too narrow for turret trucks to pass through.

As the move’s original timeline has come and gone, some remain on the fence about whether to relocate with the market, according to Bestor. (Various reports have suggested that as many as one in six vendors are thinking about not relocating.) Many factors will ultimately shape their decisions, but Bestor says four stand out.

“If one’s shop was small scale, perhaps only occupying one or two stalls at Tsukiji, there’s less incentive to stay in business since Toyosu seems oriented toward larger-scale players,” Bestor explains. “Likewise, there’s less incentive to move if your shop catered to the walk-in trade of small-scale fishmongers and independent sushi chefs.” Bestor adds that the overhead required to move and set up a new shop is substantial and may be prohibitive for some vendors. And for some longtime Tsukiji denizens, “If you don’t have an heir looking to take over the business, then you may consider this to be a good time to think about retirement and cashing out your business by selling your trading license to another mid-level wholesaler.”

The move to the new Toyosu location has also been beset with scandal over whether relocation was rushed by officials too eager to repurpose Tsukiji’s central Tokyo real estate for the 2020 Olympics. The Toyosu wharf is built on landfill that was found to be contaminated by toxic effluent from former gasworks there. Despite assurances from the former government that the soil had been remediated and would not pose a risk to food sold there, recent independent tests contradicted this position.

In July 2016 Tokyo elected a new governor, Yurio Koike, in what can only be described as a protest vote against the previous governor’s mismanaged city projects, including those involving the construction of Olympic facilities. Her election reflects the feelings of negative public sentiment that have grown with these costly, rushed and top-down urban development policies. A few weeks after her election, Koike pushed the planned November timeline into 2017 so that doubts about soil contamination at Toyosu could be alleviated.

TURRET TRUCK

A turret truck is a battery-operated machine designed to operate in very narrow aisles.

Hundreds of Styrofoam boxes filled with seafood pile up on pallets in the bustling Tsukiji Market.

CAUTIONARY TALES

If Tokyo wants a lesson on how not to handle the move, it could look to Paris’s widely deplored relocation of the Les Halles Market in the 1970s. Once called the “Belly of Paris” by Emile Zola, Paris’s historical central wholesale market was relocated to modern facilities in Rungis, a suburb. What remained in the old market area, the Forum des Halles, is considered by many to be an urban planning blight. The market’s elegant 19th-century pavilions, with their windows of wrought iron and glass, were torn down. In the old market’s place the city built a bland underground transport and shopping complex. It serves as a cautionary tale about rezoning a central economic and social institution without considering locals’ nostalgia and affection for it.

Other cities have fared better. In the 1970s London decided to move the wholesale market at Covent Garden out to the northeastern corner of the city. The Greater London Council’s initial plans for the central neighborhood involved large-scale development contracts with little concern for housing that reflected the socioeconomic diversity of its inhabitants or the small merchants that thrived on the edges of the old market. Locals successfully protested, forming the Covent Garden Community Association, and the city decided to instead renovate the Covent Garden area to foster small shops and cafes. Today it is a popular commercial area.

Sellers prepare bins of fish for the wholesalers, chefs and retail customers that frequent the market daily.

Barcelona, in the same period, closed its central Mercat del Born, opening its present-day wholesale market, Mercabarna. Plans to restore El Born as a large shopping center languished from lack of public support and private finance, until in 2002 extensive medieval ruins were discovered on the site. In 2013 El Born reopened as an archaeological museum used for cultural events, and it has since been a source of local Catalan pride in preserving local heritage.

The core market relationships that form the social infrastructure of Tsukiji will largely continue at Toyosu, whatever the fallout from the move. Tuna auctions will continue to set the standard for the world fish trade, and this will continue to be the biggest fish market in the world. Only time will tell what residues of life at the old Tsukiji market will linger in its more modern successor.

Feeding a city of 21 million inhabitants is no easy task, which is why this market has its own zip code, an independent governing body and even its own 700-man police force, which comes in handy considering more than $9 billion changes hands annually, mostly in cash. This makes Central de Abasto one of the largest economic centers of operations in the country, second only to the Mexican Stock Exchange.

Feeding a city of 21 million inhabitants is no easy task, which is why this market has its own zip code, an independent governing body and even its own 700-man police force, which comes in handy considering more than $9 billion changes hands annually, mostly in cash. This makes Central de Abasto one of the largest economic centers of operations in the country, second only to the Mexican Stock Exchange.