Investing in Tomorrow’s Food Chain: Walter Robb Moves Forward

Former Whole Foods Market co-CEO Walter Robb acknowledges that during his 26 years with the company the grocery giant helped usher in a new way of thinking about food — from farming to grocery shopping. Today, as an investor and advisor to food system startups, Robb is poised to influence the conversation again.

Walter Robb is the first to admit that it was not pre-ordained that he would become one of the modern era’s gurus of good food. After graduating from Stanford, he planned to become a lawyer, but he only lasted a week at law school. Next he tried being a teacher, a soccer coach and a farmer. None was the right fit.

In 1978, he borrowed $10,000 to open a natural-food store in an old garage in Northern California. He later sold his second store in 1991 to Whole Foods Market. By 2010, Robb was co-CEO with John Mackey, the visionary founder of Whole Foods. Sam Kass, the former White House chef and policy director for Michelle Obama’s “Let’s Move” program, says Robb has done as much to change the food system as anyone in America.

With Amazon’s 2017 acquisition of Whole Foods, Robb, 64, is starting a new chapter. Through his firm, Stonewall Robb, he’s an investor and an advisor to innovative food startups. It’s a natural next step for him — after all, he got a $10 million payout when he left Whole Foods. But his acolytes will not find Robb a typical investor. He is thoughtful, rather than brash and obsessed with disruption. And unlike many technology investors, he is not searching for silver bullets. After 40 years in food, he understands the complexity of the food chain and knows that culture and conversation will be as powerful as technology in creating a more just food system. Robb talked to Food+City contributor Jane Black about what he looks for in a startup, the importance of creating a company culture, his hopes for the Amazon-Whole Foods deal and the future of grocery stores. Excerpts, condensed and edited for clarity, follow:

Jane Black: If you Google Walter Robb, the one thing you’re definitely going to learn is that your favorite food is lentils. Lentils?! Have you always been a healthy eater?

Walter Robb: No, I wouldn’t say. I grew up in a typical upper middle-class family. We had piggies in a blanket and we had Bird’s Eye frozen vegetables — stuff like that. It wasn’t really until I got to college that I opened my eyes to some of the healthier foods and started making my own bread and that kind of thing.

Black: College isn’t usually where kids start to eat healthy.

Robb: Well, in my sophomore year I started really reading [about food]. I read Wendell Berry’s book, “Culture and Agriculture, the Unsettling of America.” And that was pretty exciting for me. And I read Frances May Lappe’s “Diet for a Small Planet.” Frances was speaking in San Francisco at Food First on Mission Street, so I went to hear a couple of her lectures.

Then I also met Alan Chadwick (a pioneer of organic gardening in California). And I spent time apprenticing with him. Between all those things, my interests in healthy eating, the soil and healthy living overall sharpened up. It kind of started me down the path.

Culture is the sum total of the humanity of the company. It’s where the culture and values come alive with a presence. It’s: How does it feel around here? How do the customers feel? How do the team members feel? That’s what culture really is. It’s an alive thing.

Black: Jumping ahead, you joined Whole Foods in 1991 and rose through the ranks. In 2004, you were named co-president. In 2010, you were promoted to co-CEO. What do you think was your biggest contribution?

Robb: It’s always tricky to say stuff about yourself. But look, I think I was part of the core team that really helped Whole Foods change the conversation about food in America. So, I’m very proud of that. I think I’m a good retailer — at the craft of retailing. I love it. My number-one quote over the years was this: “We’re not so much retailers with a mission, as missionaries with retail.”

I think I’ve definitely helped to shape the retail and culture of Whole Foods, which, as you know, is one of innovation and experience.

Black: Which leads perfectly to my next question. As the food world shifts to be much more technology focused — Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods is just one indication of the trend — how does the culture you created survive?

Robb: Well, I think you start by realizing that culture is a living, breathing thing. Culture is the sum total of the humanity of the company. It’s where the culture and values come alive with a presence. It’s: How does it feel around here? How do the customers feel? How do the team members feel? That’s what culture really is. It’s an alive thing. It continues to evolve in a way that’s malleable, and, at the same time, that it’s anchored in the values.

So now the great question is: Will two wonderful companies [with their own strong cultures] have the courage, the wisdom and the humility to learn from one another, to learn from one another’s cultures?

At Whole Foods, we acquired 19 companies under my tenure as co-CEO. It takes about two years for two companies to really come together. So the answer to your question is, it’ll happen over time. But it will require efforts on both sides to really be thoughtful about how it’s happening.

Black: What are the big issues you see coming up in food?

Robb: There’s a new set of issues up on the table. Like food waste, like imperfect produce, like farm worker health, like full transparency on product. This new generation is going to look for a more, if you will, whole foods system. In other words, one that is more fully transparent, more responsible, [with] more options.

Black: What are you working on to address these new issues?

Robb: I’ve picked some companies to invest in and serve as a director. Food Maven [a Colorado startup that sells excess food acquired from producers and distributors to restaurants and institutions at a discount] came through Grant Lundberg, the CEO of Lundberg Family Farms. He reached out to me and asked me to talk to his cousin Patrick Bultema, who’s the CEO in Colorado Springs. And I guess it was just meant to be.

I’ve been troubled as a grocer for a long time about the food that gets thrown away. About 40 percent of food grown is wasted. It’s produced, there’s too much supply and about one third of what goes to landfills is food. It’s time for that to be met with some sort of thoughtful solution. I realized, “Wow, this is something we haven’t really worked on.” Here’s an area [in which] we can make a real change. I was drawn to that. I like working on things that matter. I like working on things that have a purpose, and [working with Food Maven has been] a great opportunity to work with people I enjoyed and to try to work on something that I know needs to be done. So that was an easy one.

Heat Genie came through Danielle Pruitt, my other half. She knew Mark Turner, the CEO. It is a technology that allows a can to self-heat in about a minute and a half. Think about it. Not only do you create new products for customers [such as self-heating coffee, soup etc.], but … think about disaster situations where hot food is needed.

I liked it for that reason. I thought the company had a missionary aspect. It’s a leading-edge technology for something that hasn’t been done before, but with applications where it could make a real difference in people’s lives. Black: So it’s the fact that all of these companies has a mission that drew you to them? Robb: The criteria are a great young entrepreneur or CEO, a sense of mission or purpose in the company’s work and a commitment to building a culture that’s good for the people at the company. They need to understand and appreciate those things.

I think I look for something that’s a forward movement into the future, right? So we’re creating something that doesn’t yet exist and that is going to help shape the world. Not just something that’s been around forever that’s just kind of trodding along, but something that’s going to open new opportunities and new growth.

Black: What parts of the supply chain do you feel really need the most attention in food?

Robb: I think number one is transparency. Number two, I’d say, is quality. I’d say quality and standards so that the transparency leads us somewhere, that it’s not just an obfuscation exercise.

[Adaptation] to the digital world is also important so that it’s easy for customers to access that information and to inform their choices, and this will also help companies to evolve faster. The last big thing is the food waste.

Black: OK. The questions everyone wants answered: What is going to happen with the Amazon purchase of Whole Foods? What can Amazon do, given their position, to take good food to the next level?

Robb: Well, I’d love to see them continue to reach the full potential of Whole Foods. Whole Foods was built to endure, to be around for hundreds of years. Built to make a permanent shift in the food landscape. I’d love to see Amazon continue to honor that and accelerate it into the future. That may be self-serving because I was there so many years and it’s so much a part of me, but I’d love to see that happen.

The second thing would be to propel a more nuanced conversation about food. This often is a conversation about “Is it cheap enough?” But the reason food is not “cheap enough” is there are so many tradeoffs in the production of the food that folks don’t always know what they’re getting.

So how do we more, I don’t know, more articulately, more intelligently, more holistically approach this question about cost and quality? In the end, there always is a set of choices for people. How do we make organic food, more natural food, less expensive, but not so cheap that it loses the reason for being? How do we make people more aware of the costs that in cheap food are really not being reflected, and the costs that are happening as a result of having it? So how do we raise the quality of the conversation about that?

Telegraphing the High Price of Cheap Food

Walter Robb argues that consumers need help to make more responsible choices about what they eat. But how?

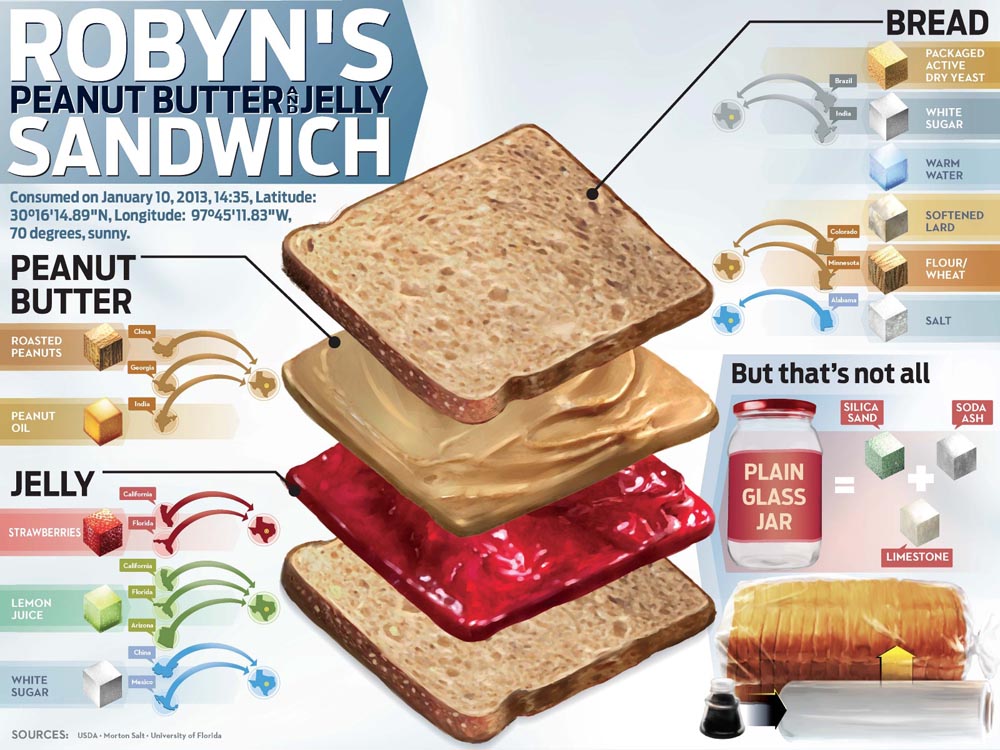

One idea: True Cost Accounting, an emerging method that tries to pin precise dollar figures on the social, environmental and public-health consequences of food production. It’s a way to price a steak to include the costs of raising and slaughtering the animal as well as, say, the cleanup costs of associated water pollution.

How to account for these “externalities” is tricky. In 2016, some 600 economists, farmers, policy makers and advocates gathered in San Francisco to discuss new ways to categorize, quantify and monetize the food system’s externalities – and, equally important, how to message it to consumers. “We need to provide the context behind stories without overwhelming our audiences with complexity,” said the Consumers Union’s Urvashi Rangan. “You give the bad news, but you also have to give people a message that empowers them and puts them in the driver’s seat.”

Black: What about all the drones and robots we hear about? Will there even be grocery stores?

Robb: Absolutely, because the need and desire for human connection is ever-present. What’s exciting about robotics is that they are already being used extensively in distribution and in physical stores as a partner to team members, doing things like checking store conditions and out-of-stocks. In Wake Fern, a grocery chain out of the southeast, you’ll see robots going up and down the aisles doing their work, increasing the productivity of the human workers. It’s already part of the grocery store. But there’s a tendency to overstate the high-tech narrative right now — that everything will be replaced.

Black: What will grocery stores of the future look like?

Robb: The world is tilting toward fresh and artisan and the true craft of food production. Soon, we’ll see [stores] in different forms and sizes. I think the big stores are in trouble; people don’t want to shop at them anymore. The whole way people get food is changing. We have so many options for food, whether it’s a meal kit, pickup or eating out. You don’t have to go to the store all the time. The grocery store is just one option. There will always be a market, but even more, it has to serve as the town square.

More broadly, the grocery store of the future will have no boundaries to it. Even though it’s a physical store, it will reach all the way into your home and even walk around with you. Imagine a Whole Foods refrigerator. You set it up on an app, pull it up on your phone, order what you want and have it there when you get home. There are also virtual reality technologies, like one from a company called Spacee, that allow you to project images of the store onto, say, a wall and enable delivery from that image.

Black: So much of this is about convenience and more personalized food. What needs to be done to create a better food system?

Robb: We need a true north. I believe in the quality of food and the transparency and the access of good-quality food, and an inclusive food system for workers and eaters. I don’t know if everyone would agree with that.

Customers are pushing hard for transparency and more information, more choices. But there are different sets of customers who can afford different things, and they are supported by commodity suppliers. These two [food systems are] running in parallel. They have different value systems.

History suggests from our experience at Whole Foods that change is possible. There are setbacks, of course. The current White House shelved a rule around animal welfare for organic that was in the works for three years. It’s two steps forward, one step back.

But directionally we aren’t going to go back. It’s a combination of things, over time, that will lead to change. But if there’s one thing we need to keep working on, it is these gaps of access and availability. We produce enough food, but it’s not finding its way to the people who need it. I would hope that the north star is an ever-increasing availability and accessibility of food that nurtures and sustains our bodies and our communities and our country. That’s what I’m going to keep working on.

Watch Walter Robb discuss business culture, a leader’s vision and how to find your passion in a Duke University video.

Watch Walter Robb discuss business culture, a leader’s vision and how to find your passion in a Duke University video.