Transcending Seasons: Following the Global Cold Chain

Prior to the late 19th century, families around the country ate only what they could grow or what nearby farmers had to offer. For people who lived where winters were frigid, that meant a limited winter diet consisting of food preserved in a root cellar. But that all changed when refrigerated rail cars enabled cross-country shipping of meats and produce from faraway farms. Access to a wider variety of foods year round changed the American diet permanently.

In 1927, the sociologists Robert and Helen Lynd published the first of their two classic studies of modernization in a midwestern community they called “Middletown.” Among the topics considered by the citizens of what was actually Muncie, Indiana, were recent changes to their diet. “In 1890 we had meat three times a day,” explained a Muncie grocery store owner. “Breakfast, pork chops or steak with fried potatoes, buckwheat cakes, and hot bread; lunch, a hot roast and potatoes; supper, same roast cold.” This would have been impossible even a decade earlier because the mass production of beef had only just become technologically viable.

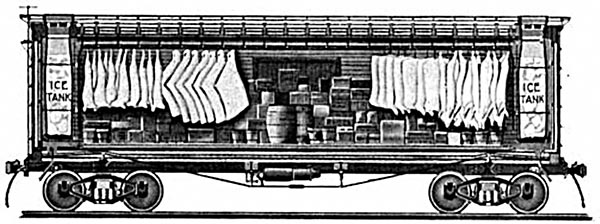

What made the mass production of beef possible? Refrigerated rail cars, thanks to Gustavus Swift’s efforts in the 1880s. By 1890, steers and pigs slaughtered in Chicago stockyards arrived in cities and towns across the country, chilled by ice for the entire route.

“Steaks, roasts, macaroni, Irish potatoes, sweet potatoes, turnips, coleslaw, fried apples and stewed tomatoes.” This is how a Muncie housewife described her family’s “winter diet” to the Lynds before refrigeration arrived there during the late 1920s. No strawberries. No eggs. The winter diet was nothing but bland winter fare. Before fruits and vegetables were protected by similarly refrigerated rail cars, producers faced substantial spoilage and could never ship in winter because delays caused by freezing weather could doom whole shipments. (While some spoilage happened during warm months, too, ventilated rail cars allowed cooling breezes, mitigating damage.)

Consumers in Muncie faced what was known as “spring sickness” because they lacked access to the vitamins they needed for months on end every year. By contrast, with the advent of refrigeration, perishable produce could arrive from California all year or be kept in cold storage for winter use when those fruits or vegetables had been grown nearby.

The year-round availability of meats and green vegetables that we now take for granted requires an infrastructure. The turn of the 20th century brought the inception of this infrastructure, which changed the American diet forever.

“Everything from eggs to apples (apart from canned, pickled or dried versions) would be seasonally unavailable without cold storage.”

As refrigerated transportation became the norm, a new type of food chain was born — the cold chain. While a food chain requires no special technologies to store and transport foods of all kinds, cold chains require some form of refrigeration every step of the way because spoilage is ongoing. If one link in the chain fails, the product becomes inedible. What was true about cold chains during the early 20th century remains true today.

COLD CHAIN

COLD CHAIN

A “cold chain” is a modern refrigerating engineering term that refers to the path of perishable foods from the point of production to the point of consumption. Unlike regular food chains, cold chains require refrigeration along the entire path to prevent spoilage.

COLD CHAINS AND THE AMERICAN DIET

Technology has always had a tremendous effect on what people eat. Some technologies have made it possible to overcome distance by making cold chains longer, while others have made it economical to get better-tasting perishables by making cold chains shorter. As cold chains (and the transportation systems associated with them) have improved, the perishable food we eat has become fresher as delivery has become faster. Cold chains even let consumers defy seasons, allowing us access to fruits and vegetables that the people of Muncie seldom saw at any time of year.

With so many cold chains for so many different foods now available, it seems much more accurate to describe our perishable-food provisioning system as an intricate cold web. The refrigerated strands of that web crisscross not just America but the whole world. Their size, their speed and, most importantly, their efficiency have an enormous impact on what we eat because they help determine how much every kind of perishable food costs, or whether that food is available at all.

EATING FARAWAY FOOD: MAKING THE COLD CHAIN LONGER

Meat was just about the most expensive food you could buy during the late 19th century. As such, it was the perfect guinea pig for testing cold chain technology — success would bring the greatest financial benefit to the pioneers. Meat producers tapped into a huge market of consumers who wanted to add more meat to their diets as both a status symbol and because of the superior nourishment meat provided, compared to their earlier diets. When technology brought down the price of meat, consumers responded quickly.

After the cold chain for meat came similar protections for fruits and vegetables, starting in the 1890s. Fast refrigerator cars full of produce grown in California could get melons or lettuce to the East Coast for consumption in about a week. Iceberg lettuce was bred specifically during this period because it could hold up to refrigeration better than the alternatives. Refrigerated shipping and cold storage made these products common all year round and ended “spring sickness” forever.

In his 2006 book “The Walmart Effect,” journalist Charles Fishman describes how lengthening the cold chain for salmon — all the way to South America — brought down the price so much that Americans can now eat that once-uncommon fish on a regular basis. While Atlantic Salmon are not native to Chile, they are now being farmed there and flown to the United States in huge quantities. As a result, writes Fishman, “[S]almon farming has transformed the economy of southern Chile, ushering in an industrial revolution that has turned thousands of Chileans from subsistence farmers and fishermen into hourly paid salmon processing-plant workers.”

Fishman stresses the importance of deboning machinery to making shipping cheap salmon economical — but that’s just because the low costs of refrigerating fish and transporting the product by air are so entrenched that they can be easily taken for granted. Thanks to advances in the cold chain that have made it possible to market fish of all kinds worldwide, Chilean salmon arrives in the continental United States faster than salmon from Alaska. Walmart has paid for preserving and marketing much of that Chilean salmon once it arrives.

Long cold chains for fish do not have to involve airplanes. Refrigerated packing crates and gigantic barges have made shipping costs so cheap that fish caught off Norway can be efficiently shipped to China for processing (taking advantage of low labor costs) and then shipped again across the Pacific to America for consumption. Cold chain shipping — by air or sea — has played a particularly important role in fish farming of all kinds, making it possible to market large amounts of fish produced in what would otherwise be isolated locations. In fact, whether there will still be enough fish in the seas to satisfy this new demand has become an open question.

HARVESTING, STORING AND PROCESSING: MAKING THE COLD CHAIN SHORTER

Orange juice is a good example of how cold chains can be physically shortened to preserve a fresher taste. “Fresh-frozen” orange juice from concentrate dates from 1952. Not-from-concentrate orange juice dates from the 1990s. Ironically, this apparently “fresh” product can be stored for up to a year before the necessary processing occurs. Once taken out of storage and pumped with flavor enhancements, fresh juice has a shorter shelf life than juice concentrate — one to two weeks. Since it bears a much closer resemblance to fresh-squeezed it can fetch a higher price than the frozen juice concentrate sold in cans.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the local food movement has revived somewhat the idea of shorter cold chains. But it may be a moot argument. Consider the pros and cons:

One reason people were supposed to buy more local food is that the energy expended on refrigeration contributes significantly to the warming of the planet. Yet, as Pierre Desrochers and Hiroko Shimzo have explained, one study found that “transporting a large volume of broccoli in a refrigerated container that had been moved around on a boat, a railroad car, and a truck to a distribution point required a lot less energy than a few thousand consumers bringing the same volume of broccoli back to their homes.”

Food miles have lately fallen out of favor as a unit of analysis because they oversimplify the environmental costs of eating perishable foods. Besides the efficiency of transport, another problem with food miles is that the energy expended to keep perishable food fresh also keeps that food from ending up in a landfill where it would give off the deadly greenhouse gas methane as it rots — a scenario in which the costs of refrigeration are less than the costs of spoilage. Similarly, the refrigeration costs associated with eating local beef may be lower, but what about the greenhouse gasses expended to raise the cow in the first place?

SPECIALIZING AND PERSONALIZING: MAKING THE COLD CHAIN FASTER

Nonetheless, some refrigerated indulgences should give any environmentally minded person pause. For example, the highly endangered bluefin tuna is an Atlantic and Mediterranean fish, yet it is regularly shipped as fast as possible to the Tsukiji fish market in Japan, where one specimen alone recently fetched $632,000. In this case, refrigeration has enabled the creation of a market that provides the perverse incentive to hunt a species to near extinction. Similarly, the Costa Di Mare restaurant inside the Wynn Hotel in Las Vegas daily flies in fish caught and frozen in Italy’s coastal waters.

One way to move faster is to travel long distances at higher speeds; another is to eliminate steps along the way. The freezer packs inside ready-to-eat meal kits allow people to enjoy their “Beef Medallions & Brown Butter Caper Sauce” and “Thai Curry Chicken with Carrots & Bok Choy” in pre-measured portions without ever having to go to a grocery store. Blue Apron, the most prominent of these ready-to-eat meal companies, sends out millions of six-pound ice packs filled with sodium polyacrylate, a powder that when mixed with water melts much more slowly than water alone. This created both a personalized cold chain and an environmental disaster, due to excess packaging.

The historian Jenny Leigh Smith has described the practices of the Soviet ice cream industry in similar terms. Unable to afford the creation of an elaborate cold chain based on mechanical refrigeration, Soviet vendors during the 1950s and 1960s simply put dry ice in their insulated pushcarts and used that to keep their product cold as they sold it on the streets. It’s a good reminder that effective refrigeration technologies are not always expensive — they just have to meet the particular needs of the situation at any point in the cold chain.

Another way to make the cold chain move faster is by using refrigeration to speed natural processes that need to occur before perishable products are sold. When the food and science writer Nicola Twilley visited one of New York City’s four main banana distributors, he told her that the energy coming off just a single box of ripening bananas “could heat a small apartment.” The firm’s ripening room was designed to control output by blowing cold air through the boxes. The ripening of some fruit is accelerated, while in other cases it gets slowed down. It all depends upon matching supply with market demand. [Read our story, “How the Bodega Gets the Banana,” for more about the long journey of this ubiquitous tropical fruit.]

TRANSCENDING SEASONALITY: MAKING THE COLD CHAIN SLOWER

When perishables are harvested in season but need to be distributed out of season, cold storage is required. The idea of cold storage dates to around the turn of the 20th century, when mechanical refrigeration was just becoming reliable enough for producers to entrust their livelihoods to these third parties along the cold chain. While new fast train lines could bring fresh-picked strawberries from Florida or melons from California to areas with harsher climates, the easiest way to defy seasonality was to store local produce in newly built refrigerated warehouses for perishable foods of all kinds.

The effects of these changes were noticeable immediately. “Twenty years ago,” explained a reporter for the New York Sun in 1894, “[p]ears which sell today two for five cents were 40 cents apiece, and black Hamburg grapes…were only to be had from hothouse growers and were worth $1 a pound. The luscious great cherries which were so plentiful a few weeks ago were unknown in our markets, prunes were known only as a dried fruit, and apricots and nectarines were rare enough to be but a tradition among the greater part of the people.” At that time, rare meant expensive, but not impossible to purchase for special occasions — for instance, buying oranges only at Christmastime.

Storage itself can be expensive even now because of the energy it requires, but it remains an essential component to using refrigeration to transcend seasonality. Everything from eggs to apples (apart from canned, pickled or dried versions) would be seasonally unavailable without cold storage.

The final link in the cold chain, the electric household refrigerator, is a kind of personal cold storage. When the first reliable, affordable, electric household refrigerator went on the market in 1927, it became an instant sensation. It meant that people no longer had to buy food quite so often as before. This was cold storage for your home. By 1960, there was a modern fridge in nearly every home in the country.

Refrigerators allow consumers to time their purchases far better than they would otherwise. In countries like France, where refrigerators are far smaller than they are in the United States, many consumers gladly visit local markets every day so that they can be assured the best flavor possible from their perishable products. By contrast, in the United States, grocery shopping only once a week is a common way to avoid the inconvenience of driving to the Walmart Supercenter and waiting in the checkout line more often. Stores like Costco, which sell huge packages of frozen goods, thrive on this American tendency to favor convenience over taste.

INCREASING FRESH ACCESS: MAKING THE COLD CHAIN MORE EFFICIENT

Future technological developments in our web of cold chains will likely occur in the parts that we don’t see. Bring the cost of storage and transport down, and producers can enter new markets or lower costs for consumers so that more people can afford to eat fresh. These changes will require increasing the scale of what travels through cold chains. Perishable products that are still too expensive for most consumers to buy regularly might become more accessible.

Dragon fruit (pitaya), for example, is well-known enough to be a flavor of VitaminWater, but just try buying an actual dragon fruit in the produce section at even a store like Whole Foods. Maybe it can be done in some places at certain times of the year, but it is far from easy. Grow the supply and cultivate the demand, and a cold chain could evolve to service it.

Apart from refrigeration itself, many important developments in cold chain history have involved improvements in transportation — airplanes or refrigerated containers for transoceanic shipping. With all the links in the chain fully refrigerated now, what might future technological improvements look like? Will your meal kits soon arrive via drone? That depends on whether it can be done efficiently and cost effectively. Improvements in the energy efficiency of refrigeration will also help increase the availability of foods to people at all economic levels if those savings are shared with consumers in a meaningful way.

Increased access to perishable foods of all kinds has been a sign of growth in our food provisioning system ever since the advent of ice refrigeration in the early 19th century. The web of cold chains this process has created stretches across the planet. Even countries that do not benefit from being the endpoint of a cold chain probably produce perishable products that could not be sold elsewhere without refrigeration technologies. While it is unlikely that the changes in diet promoted by future changes in technology can surprise middle-class Americans anymore, anything that can be done to bring the same food choices and relatively low prices to the rest of the world will benefit all of humanity.

Quick History of Consumer Ice

In the early 19th century, ice took long journeys across the globe. Cut from lakes around Boston and packed onto ships, it might be sold as far away as India. Today, anyone can get all the ice they need on demand at local convenience stores. The Ice Factory, developed in 1992, was the first of a new breed of automatic ice machines. It manufactures ice on demand and even bags it for you automatically. This eliminates both delivery and storage costs. It allows people to stock up on ice when they need it for parties and barbecues, yet still use their home freezers for their day-to-day needs the rest of the year. Prior to the Ice Factory, one ice manufacturing plant could pack enough bags to satisfy demand within a 100-mile radius.

Modern Times Cold Calling?

Expensive “smart” refrigerators, like the Internet of Things in general, are really just a way to convince consumers that they need to replace appliances that work perfectly well as-is with new ones hooked up to the World Wide Web so that they can impress their friends with how modern their home is. At this moment in time, the benefits of owning a networked refrigerator do not justify its cost. If you can send email from your computer or your phone, you have no need to send it from your fridge. Refrigerators have certainly gotten bigger since 1960. However, they don’t keep food any fresher.

History of the Cold Chain

From ice harvesting in New England to home refrigerators that can monitor their contents and send a text when you’re low on eggs, milestones along the cold chain have transformed how and what Americans eat. There was a time when pineapples and bananas were rare sites outside of tropical climates. And the idea of eating fish caught in Japanese waters yesterday while sitting in a Texas sushi restaurant today was unimaginable. No more. Check out some of the more memorable moments of the last two centuries of the refrigeration revolution.

1806

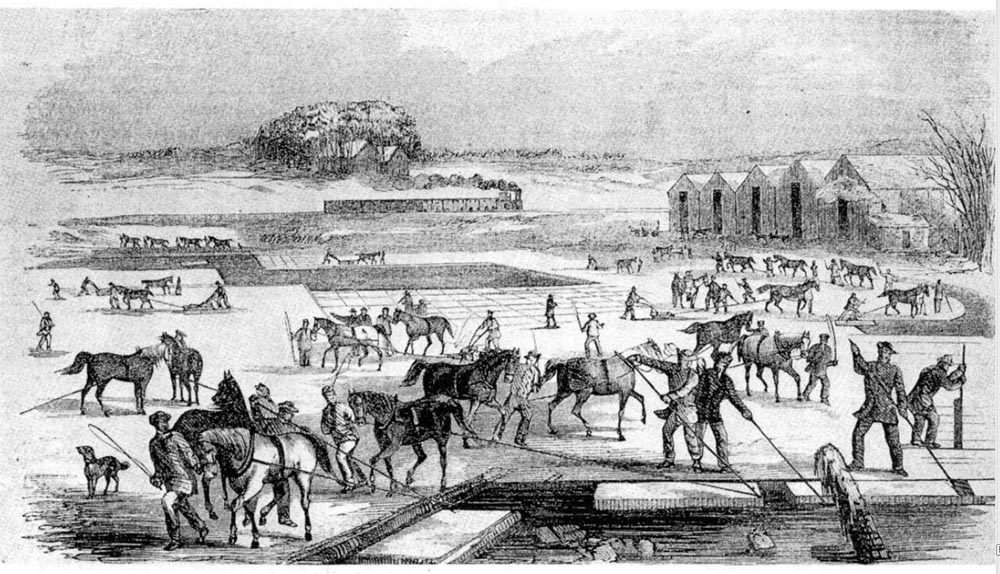

Frederick Tudor sends the first commercial shipment of ice by sea in world history from Boston to Martinique. Most of what survives the trip melts because the customers don’t know what to do with the product. Below, Tudor’s workers divide a pond into a chessboard pattern and cut ice into two-foot square blocks.

1851

Florida doctor John Gorrie patents a commercial ice machine he developed while trying to invent what we now know as air-conditioning. It does not prove commercially viable.

1878

Meat-packing magnate Gustavas Swift hired engineer Andrew Chase to design an ice-cooled rail car that would enable the shipment of processed carcasses across long distances. The result was a well-insulated yet ventilated car, in which the meat was packed tightly at the bottom of the car, and ice was kept at the top, allowing the chilled air to flow naturally downward.

1880 & 1890

The first ice famine grips the Hudson Valley. The New York market turns to Maine for its ice, leading to vast growth in the infrastructure for providing ice there and the growth of ice for domestic consumption in the United States in general. A second ice famine grips the Hudson Valley. In response, ice equipment makers work hard to improve the efficiency of commercial ice machines and largely succeed by 1900.

1916

The total number of electric household refrigerators sold in the United States tops 1,000 for the first time.

1924

Thomas B. Slate applies for the US patent on dry ice. A year later, the DryIce Corporation of America trademarked solid carbon dioxide, giving it a moniker that has lasted nearly 100 years. The company began marketing dry ice for deep refrigeration.

1925

Clarence Birdseye patents a better form of flash freezing, which will eventually make mass-marketed frozen foods possible.

1927

General Electric is responsible for bringing the cold chain into homes. In 1927, the “Monitor-Top” fridge cost around $520 — equivalent to $7,000 today — and helped lucky families keep leftovers fresh. Refrigerator design saw an update to the more familiar integrated box style in the 1940s.

![]() Check out this amazing collection of antique iceboxes.

Check out this amazing collection of antique iceboxes.

1940s

Before the refrigerated rail car became a key part of the cold chain, leafy greens like lettuce were too delicate to survive a long journey packed in ice. The solution? Iceberg (or crisphead) lettuce, introduced for commercial production in the late 1940s to be hearty enough to reach salad bowls hundreds of miles away.

1950s–70s

Railroads gradually stop using ice for refrigerated shipping as mechanical refrigeration technology becomes cheap and small enough to install in individual railroad cars.

1958

Frigidaire introduces the first frost-proof refrigerator, eliminating the need for customers to defrost their appliances at all. “Frigi-Foam” insulation allowed for the first Frost-Proof refrigerator-freezer.

1982

The Radio Cap Corporation introduced the Koozie™, a Styrofoam sleeve designed to insulate a chilled beverage from warming up due to conduction or heat radiation. Many a cold beverage will be kept cold.

1992

Jim Stuart invents the ice factory, the first ice machine that produces and bags ice cubes on demand. This eliminated the need for centralized ice production in regular, larger ice factories.

1998

The introduction of the Internet-enabled or “smart” refrigerator. Not enough people have decided that refrigerators that tell you what should be on your shopping list are worth the added expense and potential problems of buying yet another Internet-enabled device.

2006

High-end cooler brand YETI was founded in Austin by brothers Roy and Ryan Seiders. Their new design for a heavy-duty cooler that could stand up to abuse during fishing trips and retain ice for hours started as gear for serious outdoors people and has evolved into a multi-product cult brand. And it keeps your beer cold for a long time.

2012

Blue Apron begins shipping meal kits, including meats and seafood items sandwiched between ice packs to ensure freshness past delivery.

2014

Internet-enabled refrigerators, which first appeared in 1998, now have cameras and the ability to text you with messages about what might be running low inside. In the same year, both Wired and Forbes magazines published stories lauding high-tech fridges and wondering if 2014 was the year they’d finally take hold.