Make Way for Public Markets?

While farmers’ markets are become more common attractions, public markets like Pike Place or the Pittsburgh Public Market are still fairly hard to come by in urban areas.

At a gathering I attended a few years ago in downtown Austin, the breakfast fare said it all. Organic yogurt, locally produced honey, and fresh breakfast tacos broke from the usual offerings of croissants and Danish pastries. This crowd was invested in their food — emotionally and economically — as farmers, chefs, city planners, food activists, non-profits and individuals gathered to learn about the possibility of bringing a public food market to Austin. Like many urban areas across the country, Austin has farmers markets but no public market — yet. Why is that?

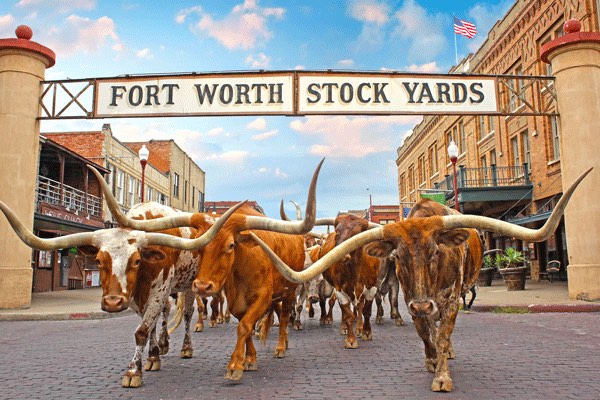

The answer requires a brief tour of public market history and our relationship with food. The relationship has always been contentious, as cities all over the world have historically been defined by their food markets and yet have moved their markets farther and farther away. Struggles over land values, sanitation and urban design have left most public food markets out in the hinterlands. And now city dwellers want them back.

“Struggles over land values, sanitation and urban design have left most public food markets out in the hinterlands. And now city dwellers want them back.”

Why? You’ve probably noticed a farmers market or two in your city, selling food from local producers and feeding a growing desire to meet those who produce our food, shake their rough hands and hear their stories.

Since the 1970s, environmentalists and the organic movement have been advocating for food to rejoin our urban landscapes, both to keep local businesses in business and to build stronger connections between producers and consumers. Some argue that the presence of farmers markets in a city adds to the social fabric, sense of community and aesthetics of the urban experience.

Why? You’ve probably noticed a farmers market or two in your city, selling food from local producers and feeding a growing desire to meet those who produce our food, shake their rough hands and hear their stories.

Since the 1970s, environmentalists and the organic movement have been advocating for food to rejoin our urban landscapes, both to keep local businesses in business and to build stronger connections between producers and consumers. Some argue that the presence of farmers markets in a city adds to the social fabric, sense of community and aesthetics of the urban experience.

Great, you say. In a digital, industrialized world, we all need more humanity.

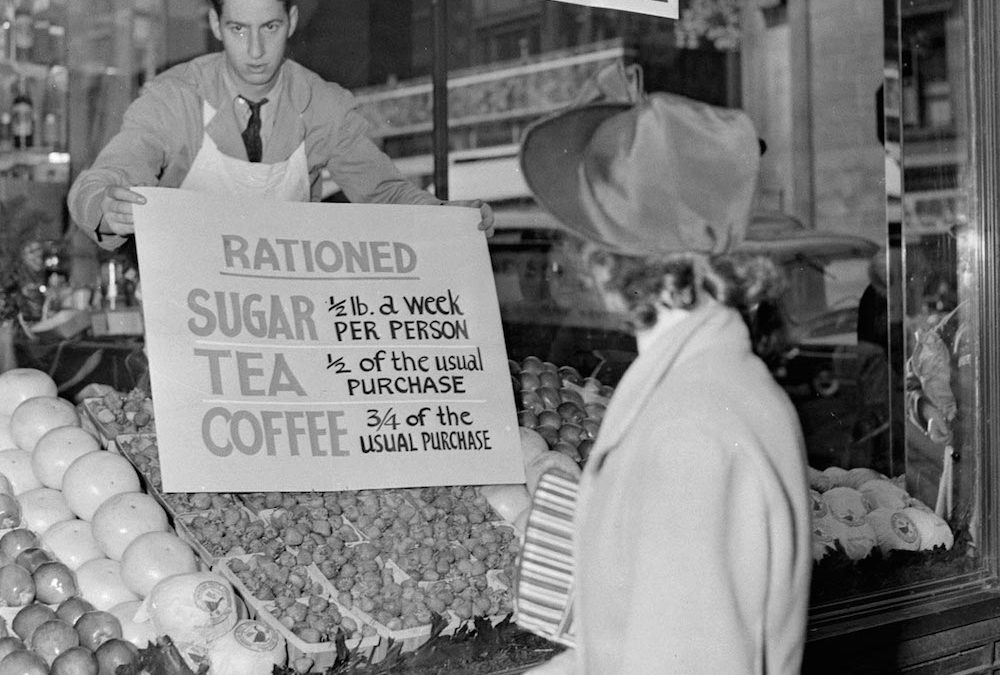

But today’s desire to bring food back to our urban landscape runs counter to the ejection of large public food markets that began in earnest during the mid-19th century when cities began to modernize. City dwellers wanted to leave behind their rough, tough rural lives. What’s more, food production was viewed as a threat to sanitation, a serious problem in the 19th century, when diseases like cholera rolled through urban landscapes. By the 20th century many cities saw their public markets as occupiers of space that could be developed to create more revenue, provide more sanitation and improve vehicle and pedestrian traffic.

A few of these public markets refused to budge, but now they seem to be on their way out, too. Smithfield meat market in London and Tsukiji fish market in Tokyo are both big historic markets that are in the crosshairs of developers and urban improvement programs. Both define their neighborhoods, have historic roots and contribute to the social and economic fabric of their host cities.

London’s Smithfield meat market opened in 1868, and Tsukiji, began its evolution as the world’s largest fish market in 1935. In Smithfield’s case, the City of London owns the land occupied by the market, and the market has come under attack several times during the past few decades because of increasing congestion around the market and the anomaly of the occupation of prime, centrally located space as a place for a wholesale meat market. The history of London’s meat market has been contentious for most of its 800-year history, so this battle for its place in London’s landscape is familiar.

Smithfield Market, in London…for now.

Some of Smithfield’s buildings have been deteriorating while the neighborhood has been modernizing and becoming a trendy area for new restaurants and businesses. Plans for a real estate company to redevelop the market were accepted and then scrapped, and now it looks as though the western buildings are to be renovated and become home to the Museum of London.

In Tokyo, the fish market, Tsukiji, has become a tourist attraction, a trend fed by the announcement of its removal nearly two decades ago. The announcement met opposition at first but then gradually gained support, even of the union associated with the market in spite of those who objected the loss of the neighborhood’s culture and history. Costs for the removal have risen but the decision to build a new market outside of the center of Tokyo will most likely stick. The arrival of the Olympic games and the need for the world’s largest fish market to conform to global sanitation requirements are important to Japan’s overall economic and diplomatic status.

In Austin, though, it looks like we’re ready to bring our food back to the city. The St. Elmo Public Market is slated to open in South Austin within a matter of months. This new experiment sits within changing tides of urban development as food markets come and go and attitudes change about how we view food, the countryside, and our public spaces. Are the battles over Smithfield and Tsukiji relevant to cities such as Austin? Or is Austin exceptional in some way that could allow it to break new ground for those who want a closer relationship with their food?

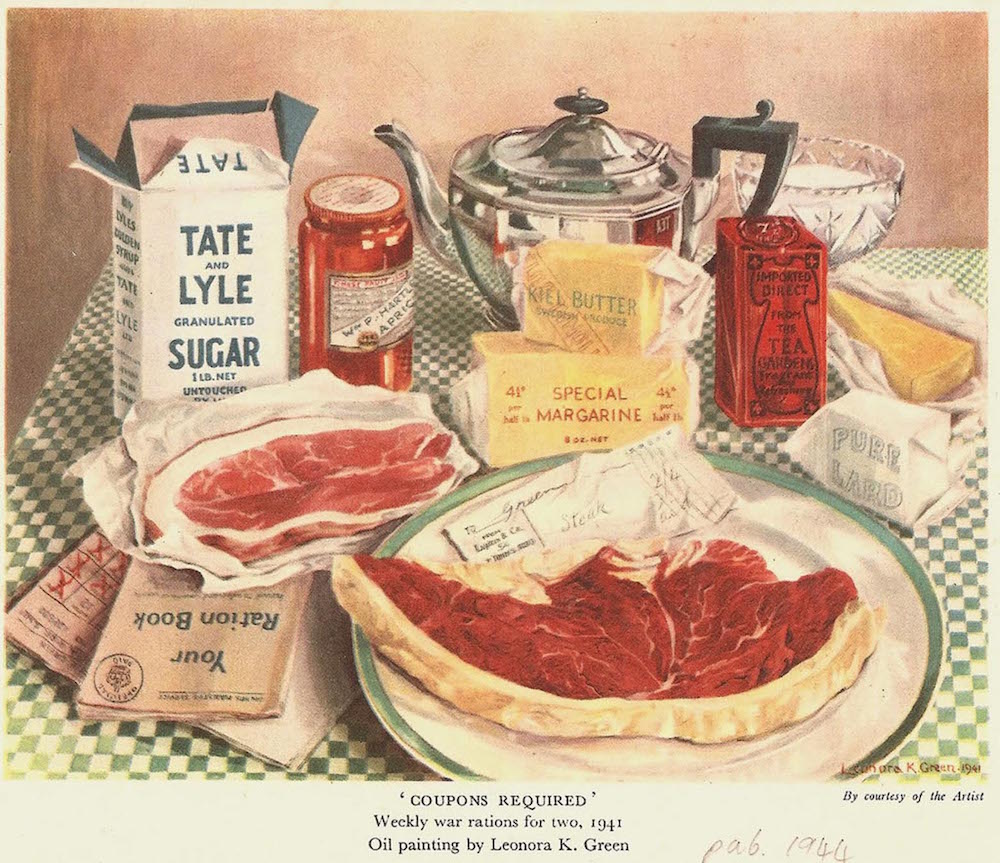

English food bloggers have shared their experiences

English food bloggers have shared their experiences