Special Dispensation: Getting Food from Vending Machines

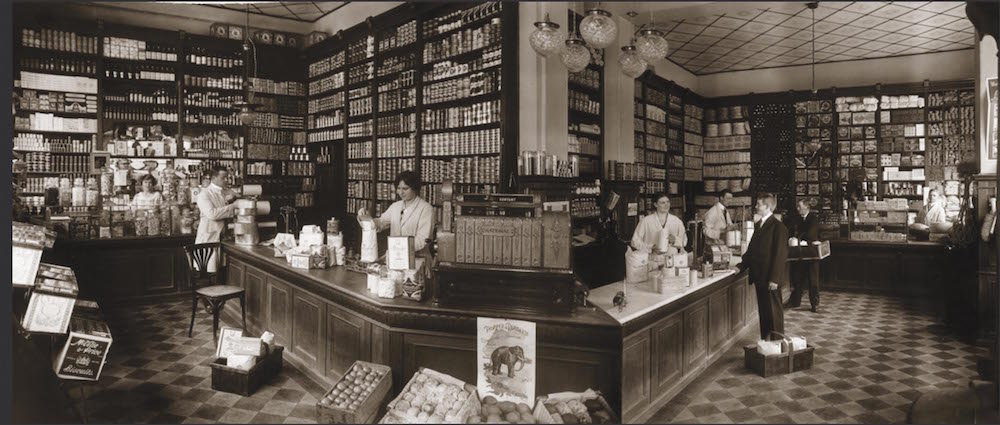

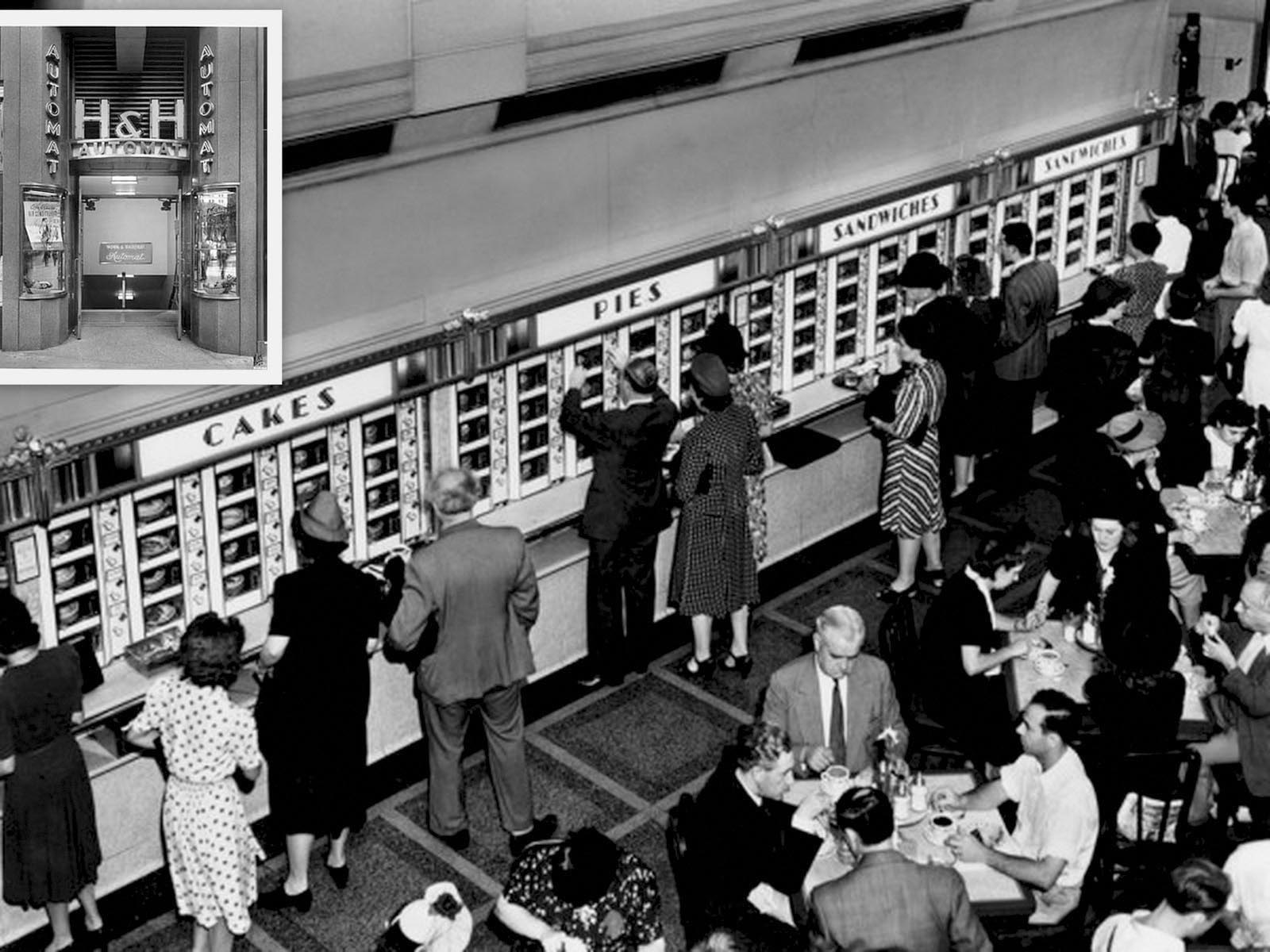

More than a century ago, Horn & Hardart revolutionized American eating with the introduction of the Automat, an automated cafeteria where a nickel or two would buy a hot plate of macaroni and cheese or a chilled slice of lemon meringue pie.

It was a new concept of self-service dining: Customers would approach a wall of windowed compartments, insert a coin and take out a plate of freshly prepared food. Behind that wall, workers restocked the compartments with food prepared at an off-site commissary and shipped to as many as 40 Automats across New York City. There was a well-lit seating area where diners could enjoy their meals, along with Horn & Hardart’s famous hot coffee.

The first Automat — a precursor to both fast-food restaurants and vending machines — opened in 1902 in Philadelphia. But Automats quickly became associated with New York City, where citizens from all walks of life rubbed elbows over lunch and dinner amid the hustle and bustle of the Big Apple.

“The Automat offered really low prices, really good food, and clean and safe surroundings,” says food historian Laura Shapiro. Automats enjoyed their heyday through the 1930s but began to decline within 10 years, she explains. “After World War II, a lot of people moved to the suburbs, and people weren’t eating dinner in the city. The prices of everything went up, food went up, labor costs went up. They couldn’t keep up that trio of price, quality and nice surroundings.”

The last Automat closed in New York in 1991. But its spirit lives on in food vending machines that connect consumers with fast-food favorites, agricultural products, regional specialties and luxury and novelty foods.

Where the Automat was a revelation of the Industrial Revolution, today’s vending machines reflect the realities of a more mobile global populace whose access to food exists in disparate contexts. The foods distributed from contemporary iterations of the Automat aren’t meant to be enjoyed sitting at a table with real cutlery at traditional mealtimes. Instead, customers can access products at any hour.

Eggs are available in Japan from machines that resemble Automats.

In Germany, consumers can access meats, cheeses and other deli items with a push of a button.

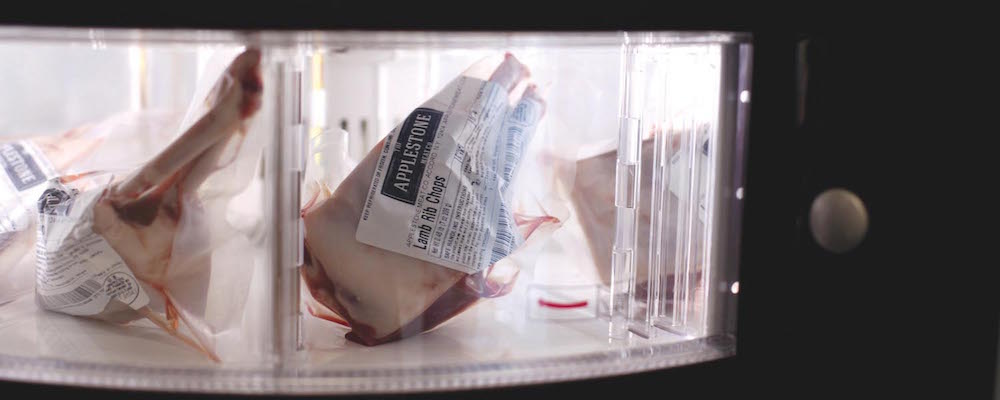

This can be a boon to rural consumers who don’t have 24-hour shops nearby, as well as to farmers seeking additional points of contact to distribute their products. You see this with egg vending machines in Japan, a pecan farm in Central Texas boasting a vending machine stocked with nuts and full-sized pecan pies, and the Applestone Meat Company in Accord, New York, which operates a 24/7 butcher shop called the Meat-O-Mat inside its meat-processing plant. The machines feature hormone- and antibiotic-free beef, pork and lamb in various cuts and are restocked every day.

In a sign that such machines could be a disruptive force in agriculture, a vending machine in Japan called Chef’s Farm can produce 60 heads of lettuce per day using 40-watt light bulbs. Designed for use in restaurants, the machine can grow up to five types of vegetables on multiple seed shelves in a temperature-controlled environment.

Vending machines also reflect regional foodways. Machines in China chill live hair crabs in a sort of suspended animation to ensure their freshness and preserve the flavor of the claws. Sake vending machines in Japan showcase rice from the Niigata prefecture. And machines in France dispense fresh-baked baguettes, Comté cheese and andouillete sausages.

These machines can even be instructive. Take the edible insect vending machine at the Museum of Natural Sciences in Houston. Patrons can snack on chocolate-covered bugs and chips made with ground cricket flour while learning about how other cultures incorporate insects into their diets.

For eaters who value convenience, there are plenty of options for mechanized grab-and-go food, from pizza in Italy to salads in jars in Chicago and piping-hot burgers and croquettes in Dutch FEBO shops. With walls of coin-operated windows displaying hot snacks, FEBO shops closely resemble the Automat and elicit similar feelings of nostalgia.

“I lived in a little town near den Haag when I was 10 or 11 years old,” says Julie Ann Holden of Austin, Texas. “I took the train to school every day and would frequently stop at the automat in Central Station for a Kaassoufflé [a kind of Dutch fried quesadilla].” There are even vending machines for luxury food items like caviar and champagne, perfectly chilled for immediate consumption at holiday parties or to give as presents to the most discriminating people on shoppers’ lists.

Making a roast? Swing by the Meat-O-Mat, a 24/7 vending machine butcher shop in Accord, New York. Click image to enlarge.

Fresh pecan pie is available at a Berdoll Pecan Candy & Gift Company in Cedar Creek, Texas.

These aren’t your standard chips. At the Museum of Natural Sciences in Houston, cricket-based snacks are part of the learning experience.

As in the Automats, these machines are replenished regularly, but few offer dining tables and chairs. Instead, the foods are meant to be consumed while in transit, whether while waiting for a flight in an airport terminal or walking the streets of Amsterdam. This extreme automation — such as at kiosks like EatZa in San Francisco and New York, where diners place orders for custom-made quinoa bowls via iPads and retrieve their freshly made meals from sterile compartments — amplifies how today’s vending machines speak to a different set of needs and desires for today’s consumer than the somewhat social Automat of yesteryear.

Gone are the days in which people sought out a full meal and maybe a little conversation at an Automat diner. But the dream of quick, easy access to all sorts of food is alive and well. At any hour of the day, People can get the food they want and need, from comfort food to hard-to-access ingredients. It’s not difficult to imagine that, along with meal-kit, grocery, and restaurant delivery services, contemporary vending machines could be instrumental in further disrupting the way our food comes to us.

There’s going to be an Automat movie! Keep up with the film’s progress at automatmovie.com.

There’s going to be an Automat movie! Keep up with the film’s progress at automatmovie.com.

MULTI-PURPOSE FOOD (MPF)

MULTI-PURPOSE FOOD (MPF)