On Our Loading Dock

Our nightstands are loaded with books to read and our laptops are packed with websites to explore and unpack some wisdom about the global food supply chain.

Books

Books

Fresh, A Perishable History

Suzanne Friedberg reveals the historical and cultural development of what “fresh” means. As early as the 1930s, consumers worried about eating too much processed food. For a fascinating look at how consumers’ thinking about fresh, frozen, canned and “shelf life” has evolved, this book lays it all out. How we feed cities will build on these histories.

Door to Door, The Magnificent, Maddening, Mysterious World of Transportation

Edward Humes reveals surprising details about how stuff moves around the world. One highlight: You’ll get an inside look at the logistics of Domino’s Pizza, which has been in the food delivery business for decades. Blue Apron and Instacart, take note.

Biting the Hands that Feed Us: How Fewer, Smarter Laws Would Make Our Food System More Sustainable

Baylen J. Linnekin examines the unintended consequences of well-intentioned food regulations. For example, how grading standards and labeling requirements contribute to the food waste we’re trying to reduce. When was the last time you met a lawyer who argued for fewer regulations, and simpler ones at that?

Feeding Gotham, The Political Economy and Geography of Food in New York, 1790 to 1860

Gergely Baics uses sophisticated maps to tell the history of New York’s food system over time, showing how market spaces took shape and how food producers such as bakers dispersed themselves over the landscape. It’s dense, but if you want to know why your grocery store is where it is today, study the maps and footnotes.

Podcasts

Podcasts

Heritage Radio Network

This Brooklyn radio station makes podcasts that explain, celebrate and challenge our views of the food system. “How Great Cities Are Fed,” moderated by Karen Karp, includes a conversation with Food+City Director Robyn Metcalfe about food logistics and the supply chain. “What Doesn’t Kill You” offers views of food system experts, including Baylen Linnekin, who explores all the complications that occur when trying to feed the world.

Gravy

Host Tina Antolini explores southern immigrant food culture, including both new and old food traditions. The podcast digs into lesser-known corners of the region, challenges stereotypes, documents new dynamics and gives voice to the unsung folk who grow, cook and serve our daily meals.

Eat This Podcast

This podcast transcends the obvious to explore how the food we eat influences and is influenced by history, archaeology, trade, chemistry, economics, geography, evolution, religion and more.

Films and Television

Films and Television

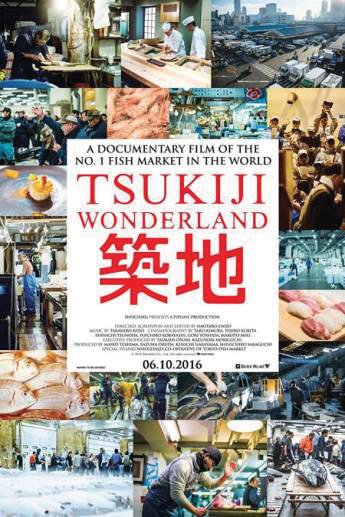

Tsukiji Wonderland

Soon after it was announced in 2014 that the cramped Tsukiji market would be moving to a larger site in Tokyo’s Toyosu neighborhood, filmmaker Naotaro Endo began shooting to commemorate this institution. Interviews with vendors plus commentary from food celebrities make this film a feast for sushi lovers everywhere.

Flowing Data: A Century of Ocean Shipping Animated

Ben Schmidt, an assistant professor of history at Northeastern University, created this seasonal, animated map of shipping paths to show how goods moved from 1750 to 1850 — long before the Panama or Suez canals opened. Imagine how those two shortcuts changed the way food moved around the world.

Food Forward (PBS)

This series appeals to our enthusiasm for visionaries and innovation within the food system. One episode suggests we might consider foraging in the woods for our food. Another visits Cornell’s Food and Brand Lab to hear from a food psychologist about how we make food choices.

Websites

Websites

BLDGBLOG (“Building blog”)

Geoff Manaugh is a writer and futurist who connects technology and humans in a way that will get you thinking about the world around you, including food logistics. Grasping the urban built environment is essential to understanding how we feed cities.