Food Movers: Rolling Refrigerators

Originally, “reefer” was nautical shorthand, referring either to the midshipmen typically responsible for trimming or reefing the sail, or to the thick, double-breasted coat worn by sailors. Today, it is old-fashioned slang for what my dictionary describes, even more quaintly, as “a marijuana cigarette.”

But since 1911, a reefer has meant only one thing in the food logistics business: a refrigerated container, capable of preserving perishables as they travel over land and sea.

“We can handle 800,000 reefers a week,” port officials brag, sounding for all the world like aging potheads. “Yeah, we’re reefer specialists,” industry insiders will say, without even so much as a wink.

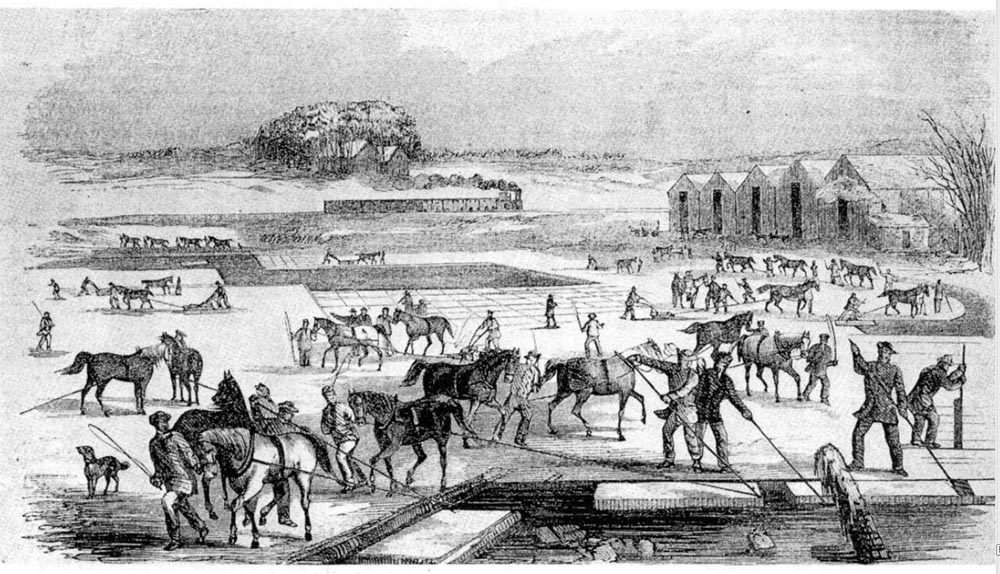

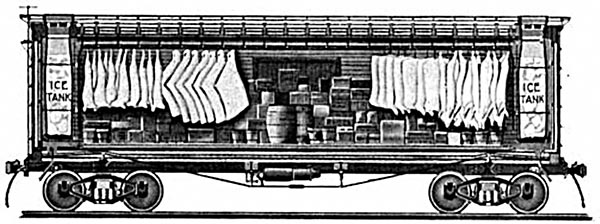

In the 1850s, those reefers would have been boxcars, bringing California lettuce and Chicago-slaughtered pork by train to America’s hungry East Coast, cooled first by ice hand-harvested from frozen lakes and then by mechanical refrigeration units. A few decades later, the term might also have referred to the chilled holds of fast-moving refrigerated ships, painted white to reflect the heat, ferrying New Zealand lamb to London and Honduran bananas to New York. Today, reefers are most likely to be special shipping containers, distinguishable from their ubiquitous peers only by the built-in cooling unit at the rear.

Nicola Twilley has long been interested in the cold chain. She curated

Nicola Twilley has long been interested in the cold chain. She curated

a 2013 exhibit called “Perishable: An Exploration of the Refrigerated

Landscape of America.”

Aluminum or steel sides protect a temperature range from -20° F to 70° F. Double full-swing doors open on one end.

Perfecting the Technology

Reefers cost six times as much as ordinary shipping containers, even before factoring in the electricity required to run them. They are correspondingly rare: despite the Chilean peaches and Argentinian steaks that fill our supermarket shelves, perishable food accounts for a surprisingly small proportion of global containerized trade. Although shipping companies are reluctant to share exact numbers, maritime industry analysts estimate that of the 25 million shipping containers in the world, only 1.5 million are reefers.

The first reefers with integrated cooling units arrived on the market in 1975, but they were slow to catch on. “Companies were moving these expensive, fragile commodities in lots of 40,000 pounds, and sometimes they would arrive OK, and sometimes they didn’t arrive OK,” explains Barbara Pratt, director of refrigerated services at Maersk, Inc. Pratt spent her 20s living inside a specially equipped reefer, trying to work out why melons from Mexico were rotting en route to Europe, and why General Food’s Dominican cocoa beans kept showing up in New Jersey covered in mildew.

Today, thanks to decades of research, Maersk offers high-tech reefers with powerful air handling systems capable of maintaining supersaturated humidity levels to prevent fruit from losing water weight as well as removing the excess carbon dioxide and ethylene gases that contribute to over-ripening. The company also issues detailed instructions about cooling cargo prior to “stuffing” the reefer, to prevent condensation.

In the past decade, reefer design has advanced to the point that specialized freezer reefers can keep sushi-grade tuna intact at minus 76 degrees F, even when the temperature outside is over 100 degrees. Meanwhile, onions and nuts, which prefer an extremely well-ventilated atmosphere, travel in their own bespoke reefers with double the rate of air circulation. Inside these finely tuned microenvironments, tomatoes remain pristine for a month or more. Maersk promises that even peaches can happily spend a couple of weeks at sea.

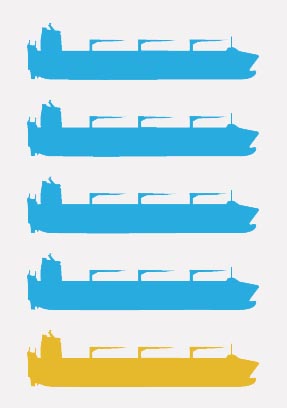

On a Reefer RoRo vessel, inside decks are convertible to reefer holds with 10 separate temperature zones, all gas tight. It was specifically designed for the large banana and pineapple trades across oceans. And it meets the newest environmental requirements for a ”green vessel,” with liquid natural gas as a fuel option for both propulsion and onboard refrigeration. It was collaboratively designed by Reefer Intel AG, Naval Architects Kn. E. Hansen A/S, Denmark, and Stena RoRo AB, Sweden.

Ocean-going Perishables

In response, more and more fresh food producers are choosing reefers instead of old-school refrigerated-hold ships or expensive air cargo. Container Management magazine recently speculated that specialized reefer ships might well go extinct sometime in the next few years, as the perishable sector finally undergoes the containerization revolution that transformed the rest of the logistics universe in the 1950s and ’60s.

But improved technology is only part of the reason why the seaborne perishable trade has grown so dramatically over the past decade — a trend that industry insiders expect to continue in the coming years. In the United States, for example, retailers have noticed increased sales of fresh fruit and vegetables, and a corresponding slump in the center aisles, as shoppers increasingly favor refrigerated produce over its canned or frozen equivalent. Meanwhile, in China, a booming middle class is eating more meat, much of which arrives in reefers from Brazil. Even millennial snacking trends have had an effect on global reefer movements, with Maersk launching a Mexico-to-Yokohama avocado route in 2016.

One fruit, however, remains a constant: the banana. Both Dole and Chiquita call at North America’s biggest banana port, Wilmington, Delaware, twice weekly, year-round, to supply tropical fruit to the 200 million people who live within 24 hours’ drive. Indeed, while any kind of cargo that is sensitive to atmospheric conditions can be found inside a reefer — French wine, high-tech Italian ski equipment, Japanese bonsai — Maersk estimates that every fifth reefer on the high seas is stuffed with bananas. They are cut and transported while green, hard and immature, their development delayed with cold storage until they are just a week away from delivery, when they are warmed up and gassed with plant hormones into artificial ripeness.

It is in the banana’s complicated journey from tropical treat to global commodity — with all its technological progress, economic impact, dietary shifts, agricultural diseases and Central American political instability — that we can see the story of the reefer most clearly, in all its time-and-space-distorting might.

Maersk estimates that every fifth reefer on the high seas is stuffed with bananas.

Watch Walter Robb discuss business culture, a leader’s vision and how to find your passion in a Duke University video.

Watch Walter Robb discuss business culture, a leader’s vision and how to find your passion in a Duke University video.

COLD CHAIN

COLD CHAIN