Food for Thought: Smart City Tools, Then and Now

Food technology — gizmos such as blockchain, sensors, taste algorithms, genomic tracking — is a hot topic these days, generously funded by venture capitalists. But food technology has been around for decades. Can openers, anyone?

No one would dispute that a GPS tracker is sexier than a simple can opener. But those early inventors deserve credit for laying the foundation for today’s innovations. After all, it took almost 50 years after the can was invented before someone made an opener for it. Our everyday can opener — the rotating serrated-wheel device — first appeared in 1870, and it’s still in everyone’s kitchen drawer, nearly 150 years later.

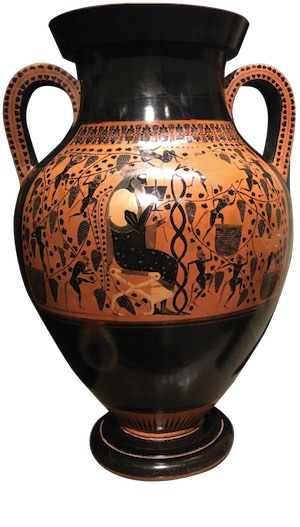

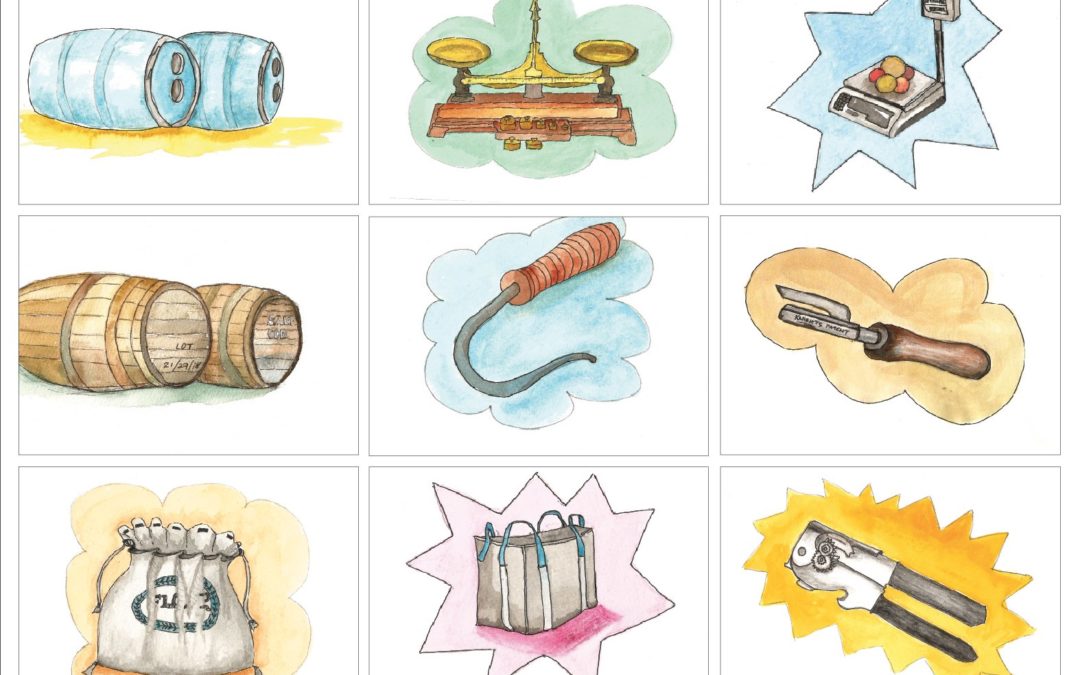

Food storage technology developed from clay amphorae and wooden barrels to polyethylene drums with lever-lock rings for transporting food commodities such as cooking oil. Today, wooden barrels appeal to artisan fermenters and brewers who embrace the flavor-enhancing properties of wood. Sacks and bags continue to transport our food from the grocery store to our house or from the coffee plantation in Kenya to our roaster in Brooklyn. Some are still made of cloth, paper and hemp, while others are big, woven-plastic buffle sacks that optimize space in container ships.

Weights and measures are the quants of food markets. Beginning as bowls and rocks in the Indus River Valley, weighing scales used balance mechanisms, such as this early 19th century balance scale, until the digital age arrived in the early 1980s. Not quite the graceful scales of the past, these digital scales are more sensitive and adapt to multiple units of measure.

Maintaining its utility throughout the ages is the meat hook, the hand tool for butchers and meat processors. The only difference between this 19th century hook and today’s version is the handle: one is wood and the other plastic. Some technology endures the test of time.

English food bloggers have shared their experiences

English food bloggers have shared their experiences

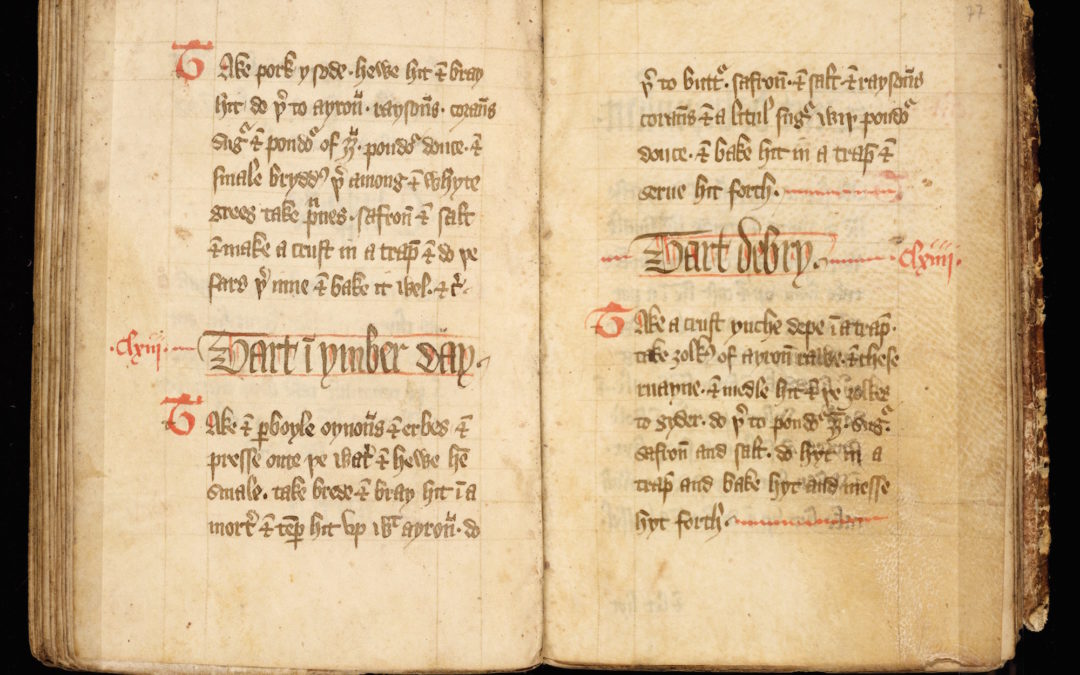

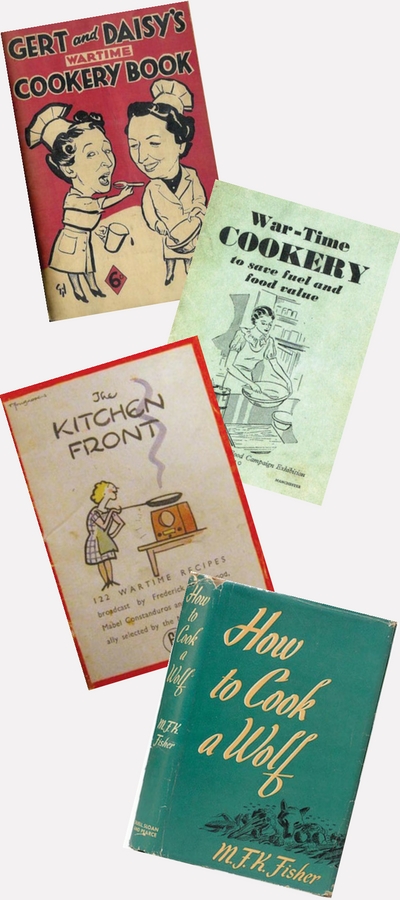

Books

Books

Podcasts

Podcasts

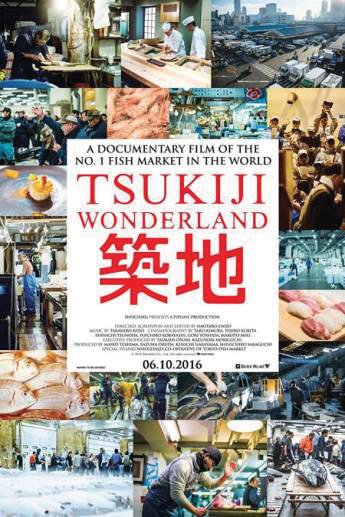

Films and Television

Films and Television