Food Movers: Can I Get That To Go?

The pressure on food to perform has never been higher. For decades, pizza boxes, Styrofoam clamshells and the paper pails used for Chinese takeout each filled a specific niche in the restaurant industry. But during the delivery gold rush of the past 10 years, restaurants, food packaging manufacturers and customers are demanding more.

The original delivery foods (pizza, Chinese food, deli sandwiches and burgers, which became delivery staples in the 1960s and 1970s) don’t suffer in quality from the half-hour they might spend en route to your house. In contrast, many dishes offered today at casual eateries or fine-dining restaurants weren’t designed to be served in the insulated boxes of past decades.

Lynn Dyer, president of the Food Packaging Institute in Washington D.C., notices small changes: the tabs that make the containers easier to open, the discreet vents that allow steam to escape, the perfectly clear plastic that enables you to see your food before you open it.

Dyer says the innovation we’re seeing for 21st century delivery demands rivals the changes we saw during the fast-food drive-through boom of the 1970s and 1980s. Years ago, her industry group worked with auto companies to determine how many cupholders a car needed and what size they should be. Those measurements were originally used to design drinking cups, but now French fries, chicken nuggets and salads are packaged in cupholder-friendly containers.

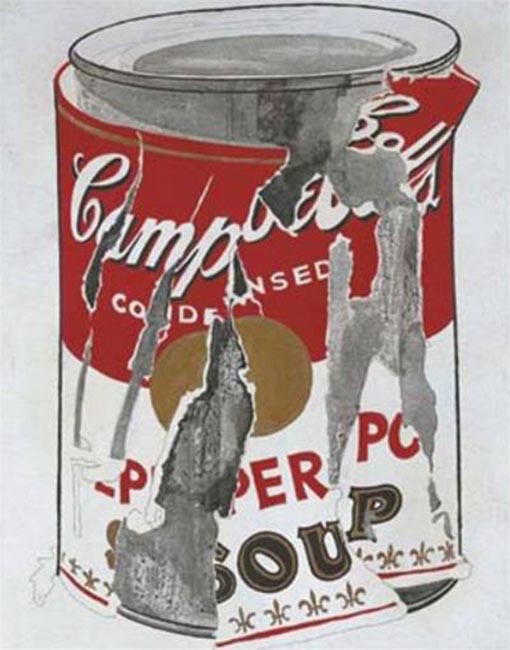

PACKAGING FOR VISUAL IMPACT

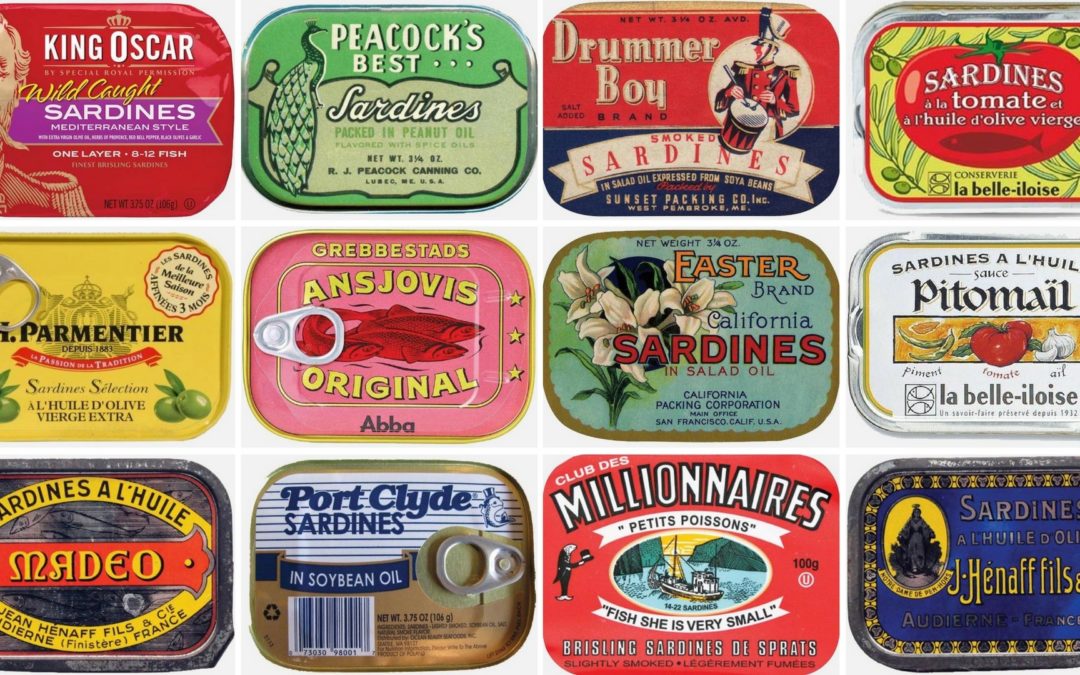

Modern food packaging containers aim to create a “wow” moment for customers when they unpack their food. That’s why we are seeing Instagram-friendly logos, shapes, colors and clear plastic lids to show off the food, Dyer says.

We eat first with our eyes, but for chefs like Austin’s Rebecca Meeker, food quality is the top consideration. In her fine-dining days, she sent leftovers home in compostable containers. But today, every single food item from her company Lucky Lime is delivered. She needs containers that won’t get soggy and that will hold temperature so that when the food finally arrives, the customer will enjoy their dining experience as much as if they were in a restaurant — the packaging and flavors having fulfilled the website’s promises.

Safety is a concern, too — particularly when your delivery driver may not have a working tie to the restaurant. Manufacturers are working on tamper-evident packaging, such as a takeout bag with a tear strip on the top so a customer can see if someone has opened the bag since it left the restaurant.

COOKING FOR THE ROAD

Few restaurants start out with a plan to meet a growing demand for takeout. But in an increasingly cutthroat industry, many restaurateurs have little choice. Delivery adds expense and opportunity for error, but if a restaurant doesn’t offer its food to go, potential customers will go elsewhere to get it. Dyer says many restaurants consider packaging a small price to pay to make additional sales from people who aren’t sitting in their dining room.

“Foodservice operators want consumers to have the same experience as if they are in the restaurant,” Dyer says. “If they get the food delivered and it looks like a big mess, you don’t get the same experience.”

DELIVERY, NOT DOGGIE BAG

At Lucky Lime, Chef Meeker designed every dish with delivery in mind. For her delivery-only venture, Meeker developed healthy Asian-influenced dishes — with a French flair — that she knew would hold up during a car ride.

She prefers containers with clear tops (so customers can see the food) that seal securely so spills aren’t a problem. These days, one spilled container could mean a customer doesn’t come back, or worse: leaves a negative review about a delivery company that can’t deliver. But finding the perfect packaging can be a challenge.

“You want to highlight the food, but it adds expense,” Meeker says. She says she spends about $1 per order on packaging, often more if the delivery includes a drink in a plastic bottle.

Meeker uses about eight different containers for her limited menu delivered cold once a week. If she wants to add a hot menu, that’ll require a new set of packaging. Grease- and moisture-resistant compostable packaging has been around for about a decade, but some businesses prefer recyclable plastic, which can hold heat longer.

Meeker can’t order the compostable, molded fiber containers with the clear plastic tops that she’d really like to use because her sales are too small to meet the required minimum purchase of $750 every other week. For now, the recyclable containers she’s already using will have to do.

Some Like It Hot

More than 60 percent of Mama Fu’s business is to-go or delivery. Customers of this fast-casual Asian chain expect their food to still be hot when it arrives, and they want it in a reheatable container, says Director of Marketing Josh Churnick. The company, with two dozen locations in Texas, Arkansas and Florida, skipped the traditional paper pail and opted for bright red trays that customers can wash and reuse at home. “I hear from customers on a regular basis who have cabinets full of red containers.”

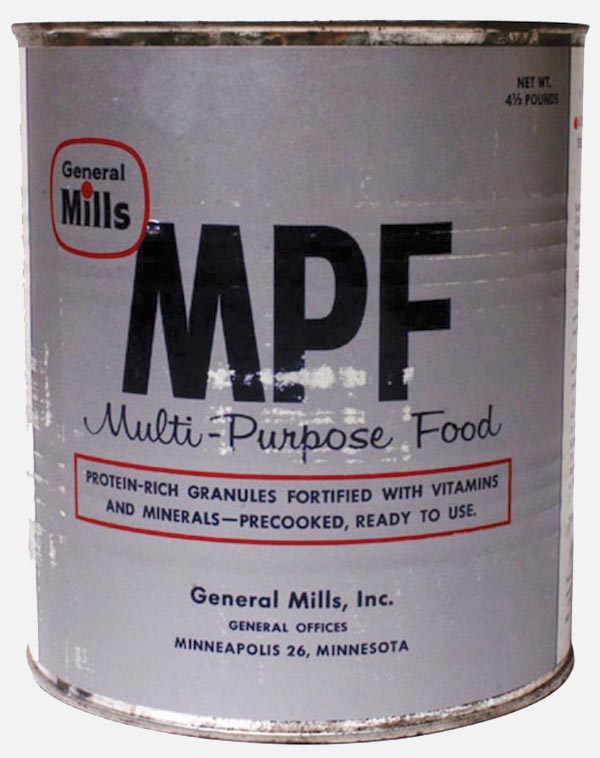

MULTI-PURPOSE FOOD (MPF)

MULTI-PURPOSE FOOD (MPF)

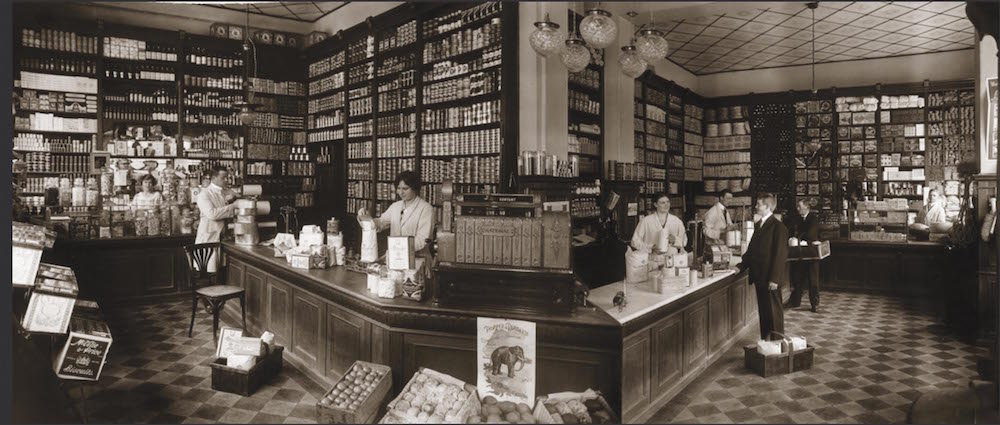

Need a refresher on how to play Kick the Can?

Need a refresher on how to play Kick the Can?