Cutting Waste Across Cultures

The United Nations has proposed a goal to cut global food waste in half by 2030. Liz Goodwin, a senior fellow and director of food loss and waste at the World Resources Institute (WRI), has taken that mandate to heart. Goodwin, of all people, would know what that entails. During her tenure as CEO of the U.K.-based Waste and Resources Action Programme, U.K. food waste fell by 21 percent. Now she seeks to take lessons learned from that effort and apply them to other countries that have very different challenges with regard to food waste.

The specific opportunities to prevent food waste vary from place to place, Goodwin explains, for reasons that are cultural, economic and tied to infrastructure.

In China, the world’s most populous nation, good hospitality would suggest that as much food remains on the table at the end of the meal as was there at the beginning. Otherwise, it sends the message that the host hasn’t provided enough to eat. However, Goodwin notes that it’s heartening to see that the Chinese government has been encouraging people not to waste food at banquets and events. Many Muslim countries have similar edicts that are in direct conflict with the goals of preventing food waste. Meanwhile, many modern industrialized societies such as Switzerland and Singapore impose unnecessarily cautious food expiration dates, which results in the disposal of perfectly edible food.

By contrast, poor countries have less waste in the home than in wealthy nations, Goodwin says. Leftovers don’t go bad in the fridge when hunger is an issue. Food scraps are more likely to be fed to animals or composted. But waste isn’t a non-issue. In developing nations there are gaping holes in the supply chain infrastructure through which large amounts of food are lost.

“With slow transport and unrefrigerated storage conditions, the food just doesn’t get through to the end user in time,” Goodwin says. “And then there are gluts of food, such as massive numbers of mangos that ripen at the same time, and no infrastructure in place to process it all.”

In the developed world, the biggest source of food waste is in private residences. It’s where 70 percent of food waste happens in the U.K., and there are a range of causes, including getting portion sizes wrong, not using leftovers and letting food expire or go bad before using it.

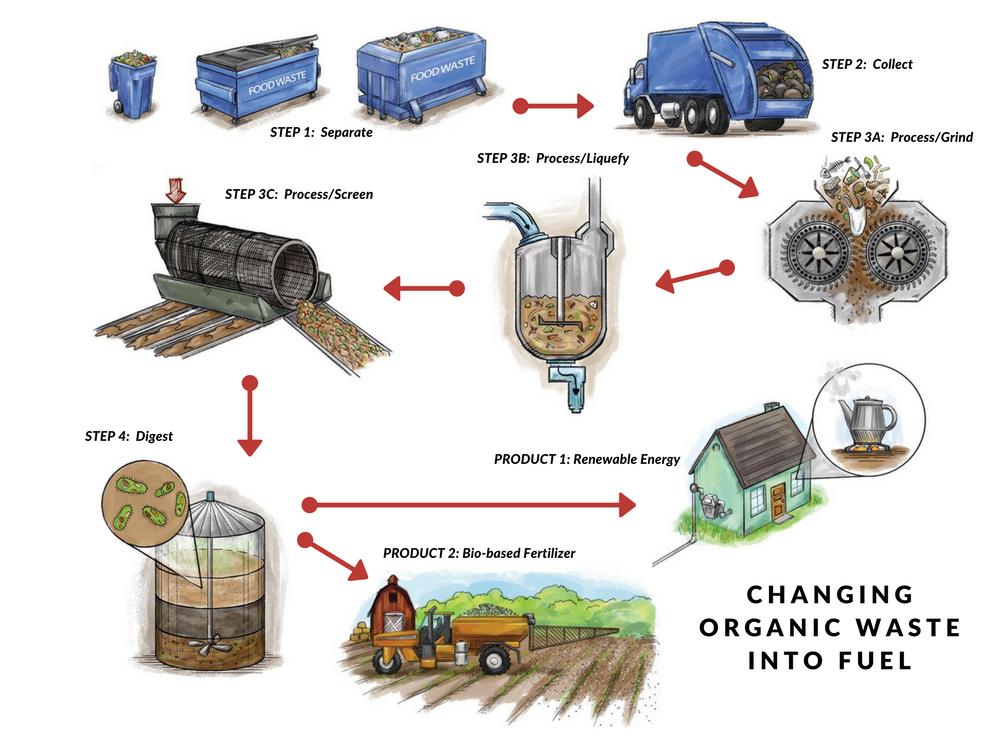

On the other hand, food waste is less of a problem in commercial or institutional settings. “Organizations can control what goes on within their operations,” explains Goodwin, referring to the large farms, processors, distributors, grocery stores, institutional kitchens and restaurants where food is flowing. Not only are these big players easier to work with, they can make big deliveries of salvageable food that could be diverted from the waste stream — or of food waste that can’t be eaten but which can be digested anaerobically and converted to energy and fertilizer.

The world’s two most populous nations, India and China, have both first-world and developing world conditions. “China and India have a mixture of developed-world problems and developing-world problems. Their populations are big, and they are producing a lot of food, so supply chain issues are really important.”

With such differences from country to country, Goodwin explains, the first thing to do when evaluating a nation’s food waste profile is to look at where the food waste is happening. Is it in restaurants, the household or at various points in the supply chain?

“Start measuring,” she says. “Because that will help to identify where their biggest issues lie.”

LIZ GOODWIN, SENIOR FELLOW AND DIRECTOR OF FOOD LOSS AND WASTE AT THE WORLD RESOURCES INSTITUTE (WRI)

From 2007 to 2016 she was CEO of Waste and Resources Action Program. During her tenure, recycling rates in the U.K. increased from 9 percent to 43 percent, and U.K. food waste was reduced by 21 percent. At WRI, her goal is to work with people and organizations around the world to cut global food waste in half by 2030, in line with UN sustainable development goals.

Keep up with the latest in food repurposing and follow Claire Cummings on Twitter

Keep up with the latest in food repurposing and follow Claire Cummings on Twitter