But when they began asking around, they learned that companies of all sizes had a more pressing problem: navigating day-to-day deliveries. While routing solutions such as Roadnet® — one of the largest — do exist, these technologies planned routes the night before. They couldn’t make real-time adjustments if a snowstorm hit, traffic got snarled, loading docks filled up or the customer didn’t turn up to receive delivery.

Along with potential customers voicing their needs, MIT advisors noted the same challenge existed in the U.S. Using harvested data as a backbone, the team tackled the complex problem of route optimization for the shipping and logistics industry. Here was the answer to their assignment: a technology to offer nimble routing using big data, machine learning and cell phones.

The first thing they discovered was that most traditional delivery routing systems weren’t accounting for the volume of available open-source data that could reveal historical patterns such as traffic and weather. The team created several algorithms that take in passive data, including historical service times or traffic patterns as well as direct feedback from drivers using their prototype — a straightforward mobile app for drivers to follow, paired with a web-based tool for managers to review.

The students searched for companies willing to share data so they could test it. That part was easy.

“We would cold-call companies on LinkedIn and say, ‘MIT and big data,’” says Shaikley with a laugh. Apparently, that combination was enough to pique interest. To better understand drivers’ challenges, Shaikley rode along with them. “I’d hop in these giant trucks and watch them use our app,” she says. “It was like standing in front of a crowd naked. Drivers are sharp and they know what they’re doing.” And they had immediate feedback: Drivers were critical of the abundance of in-app messaging. How could they deal with a ton of pop-ups while on the road?

After two years of fine-tuning their proof of concept, the team made it official, incorporating the business and naming it Wise Systems. After graduation in 2014, they joined an MIT startup accelerator. When they wrapped that, they searched for paying clients.

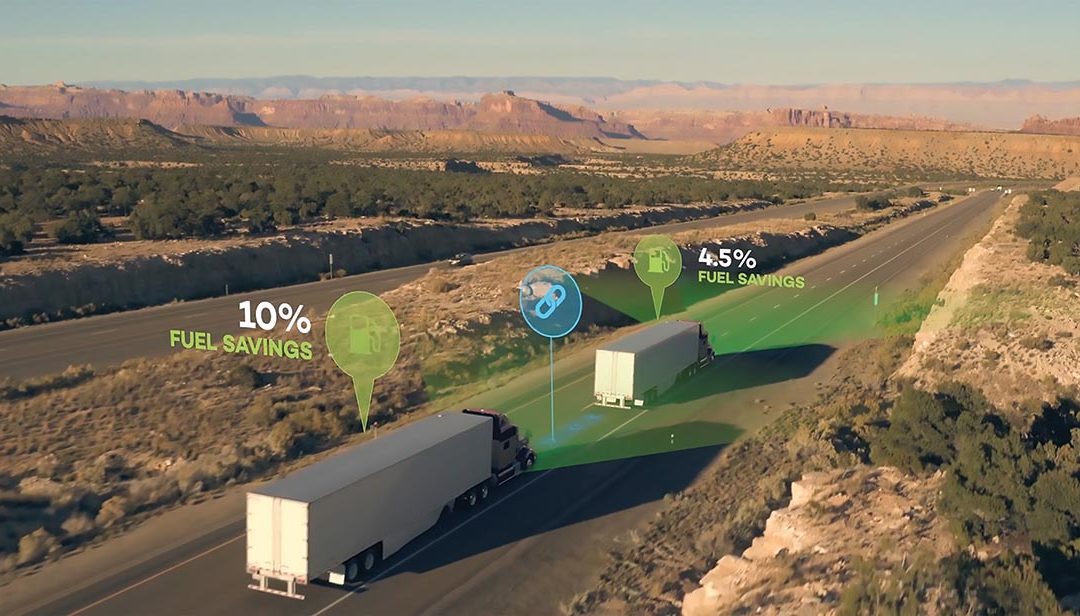

Through an advisor at the MIT Center for Transportation and Logistics, they were introduced to Anheuser-Busch. They walked the beer giant through their process, explaining that by using data such as traffic, cancellations, late customers and weather, the Wise algorithms adjust drivers’ schedules on the fly. This means “they can make the most efficient decisions possible” about navigation and order of delivery, according to Chazz Sims, Wise Systems CEO and co-founder.

In 2016, Anheuser-Busch agreed to run a pilot using Wise Systems in two locations: Seattle and San Diego. The company still used Roadnet, its existing technology, for its route pre-planning, but it used Wise for day-of routing. Several months later, when Anheuser-Busch reviewed the metrics — driver satisfaction, shorter routes, quicker work time — they were impressed enough to roll the Wise launch out to every single U.S. wholesaler, plus two locations in Canada.

Wise’s success with the beer giant demonstrates the novelty of their solution — real-time route optimization.

“People think this is solved, but it’s not,” says Sims. Case in point: UPS spent billions to create its in-house system, called Orion. Initiated more than a decade ago, the system didn’t launch until 2016, with the help of 500 staffers working on the technology. In contrast, Wise has a staff of 15. While UPS has incredible numbers — handling 15.8 million packages on an average day — imagine how much technology has changed since Orion was initiated. A UPS spokesperson noted that real-time optimization, including real-time navigation and updates after each stop, won’t be fully deployed until 2019.

Wise’s app makes extensive use of third- party tools — including mapping, weather, traffic and navigation — and focuses solely on the algorithms that take in the data and create flexible day-of schedules.

“We pull real-time traffic, we look at history, we make projections of what the rest of the day will be like,” says Sims. Taking into account that specific route’s history, the software determines that if a driver continues with his or her current route, a delay is likely. At this point, the Wise app alerts the driver to a route change, which the driver can accept or reject based on his or her experience with the trip.

Shaikley calls drivers’ collective experience “tribal knowledge.” A driver who hits the same stop week after week knows some customers have good and bad times for deliveries. Maybe the Coke delivery guy will be there at the same time, maybe parking will be terrible, perhaps the customer is out for his daily coffee.

“They [drivers] can add their own knowledge and insight into the app, and we can take in the feedback,” says Sims, noting that future algorithms for a specific route would include those updates. Shaikley emphasizes their goal of being a driver-first solution.

With several new contracts on the horizon, Wise Systems is making progress expanding the business and plans to capture new market segments in 2018. They will have helped the delivery of 10 million packages by the end of this year by homing in on a single part of the puzzle: flexible routing. For a project that started as a grad school lark, Shaikley says they’re chipping away at the original goal of changing a billion lives by focusing on drivers. “Understanding what is in their heads is the most valuable.”

Keep up with the latest in logistics entrepreneurship and follow Layla Shaikley on Twitter

Keep up with the latest in logistics entrepreneurship and follow Layla Shaikley on Twitter